Describe an item you were incredibly attached to as a youth. What became of it?

Friday, 10th January, 1919

The frost had put a skin on London that morning, a thin, bright hardness over the usual grime, so that even the puddles along Whitehall shone like broken glass. Elsie Barnett walked as if the pavement might crack under her – careful, measured – though it was not the ice she feared. It was the thought of what sat in her coat pocket, heavy as a coin and twice as accusing.

Traffic moved in a reluctant stream: a motorcar nosed past a cab, a lorry clattered, a cyclist hunched against the cold. Men in civilian coats that still hung like uniforms loitered in knots, smoking, waiting, pretending not to wait. A soldier in demob clothes – cap too big, boots too dear for the rest of him – stood with his hands jammed in his pockets, watching the War Office as though it might spit out his future if he stared long enough.

Elsie did not stare. She kept her eyes on the flags, on the stone, on the blackened lions, on anything that was not the invisible queue of grief behind her.

Her gloved fingers closed around the object in her pocket and, for a moment, she was not twenty-three but twelve, standing at the kitchen table in Camberwell while Tom – Tom with ink on his thumb and a cowlick that would not be tamed – declared, with a solemnity that belonged to sermons, that a compass could not lie. North was north. That was the marvel of it. If you were lost, you did not have to ask anyone. You did not have to trust them.

“Here,” he had said, and placed it on her palm as if making her a gift of law itself. The brass case had been warm from his pocket; the glass had caught the lamplight and turned it into a small, controlled sun. “Look, Els. See? It knows.”

And now she was here, walking beneath stone façades that did not know her name and would not, if they could help it, know Tom’s either.

The War Office entrance loomed, its steps rubbed smooth by boots and authority. A constable stood nearby, moustache bristling like a warning, eyeing the passers-by. Elsie’s throat tightened in the old, familiar way – half anger, half shame – because she had a right to be here and still felt as if she were trespassing.

She paused at the foot of the steps and drew a breath that tasted of coal smoke and cold iron. In the pocket of her coat the compass pressed into her knuckles, round and unyielding. The brass had lost its shine. It ought, if anything in this world were orderly, to have been lying in a drawer somewhere with Tom’s other effects, or sunk in foreign mud, or melted down with the rest of the nation’s promise. It ought not to be here with her. That, in a way, was the trouble. The trouble and the only hope.

Inside, the air changed: less street, more paper. The corridors held a dry, institutional warmth, like a room kept for specimens. Footsteps sounded sharper. Voices dropped into a particular tone – sensible, economical, as though every syllable were stamped.

A clerk at a desk looked up as Elsie approached, his eyes flicking at her face, her coat, the set of her mouth.

“Business?” he asked, already tired of her answer.

“I’ve an appointment,” she said, and slid a folded letter across the desk. Her voice did not tremble. She had learned to keep it steady in wards full of boys calling for their mothers. She had learned steadiness the hard way.

The clerk took the letter with two fingers, read the top line, and his manner altered a fraction – not kinder, not crueller, merely shifting to the correct pigeonhole.

“Miss Barnett,” he said, as though her name were a form. “You’ll wait there.”

He pointed to a wooden bench along the wall where a man in a cheap suit sat with a hat on his knees, staring at the floor as if it might offer a better sort of answer than the desk. Elsie sat at the other end of the bench, back straight, hands folded. Her pulse thudded in her wrists. The compass ticked against her palm as she turned it inside her pocket, feeling the shallow dent on its edge.

A door opened somewhere down the corridor. A woman’s laugh – brief, shocked, quickly smothered – escaped and was shut in again. A messenger boy hurried past carrying a bundle of files, his boots leaving wet crescents on the linoleum. Elsie’s gaze snagged on the spines of the folders, each labelled in neat hand. Names. Numbers. Lives pressed flat.

She thought of Tom’s name on the list in the newspaper – spelt wrong, as if the printer had sneezed and no one had cared enough to correct it. Barnett had become Bennett, or perhaps it was the other way round, and the error had the weight of a verdict. Her mother had held the paper as though it were a telegram, fingers trembling, and said, “That isn’t us,” as if the mistake might, by being noticed, unmake the death.

But death did not care for spelling. Only the living did.

After a time that felt like punishment, the clerk called her. “Miss Barnett. This way.”

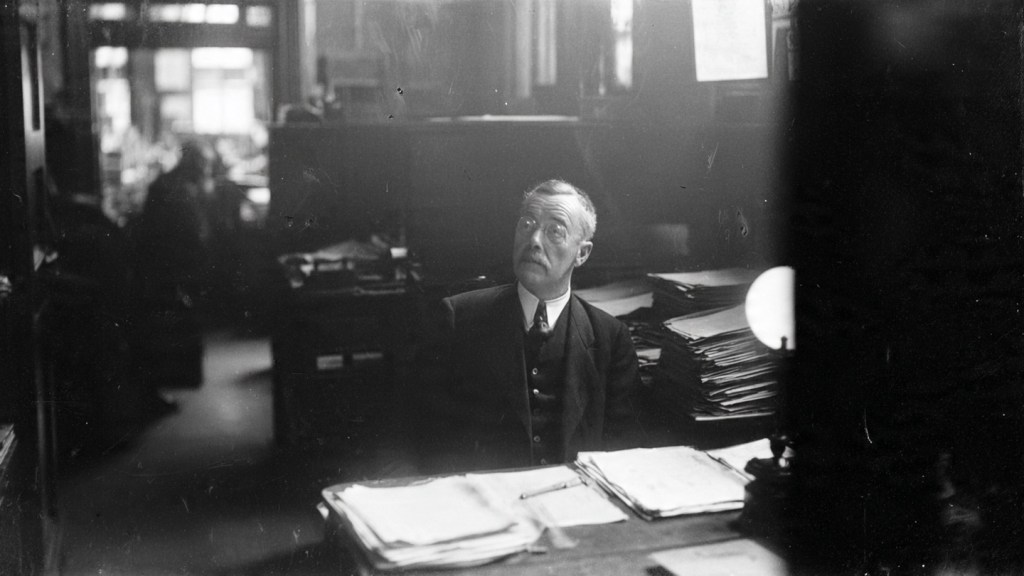

Elsie followed him down a narrow passage that smelled faintly of ink and damp wool. He opened a door without knocking. Inside, a small office: a desk, two chairs, a fire that gave more smoke than heat. Behind the desk sat Mr Swithin.

He was not the sort of man Elsie had expected when she was younger and imagined “the War Office” as a single looming creature with a mouth full of medals. Mr Swithin was ordinary in a way that was almost offensive. His hair was thinning at the temples; his collar sat a touch too tight. His hands, when he rose, were ink-stained, the nails clean. A man who had spent the war indoors and looked ashamed of it without quite admitting why.

“Miss Barnett,” he said, and inclined his head. He did not offer his hand; perhaps he did not know whether it would be welcome. “Do sit down.”

His voice had the careful polish of a clerk who had had to deliver bad news often enough to learn that gentleness can be a kind of armour. Elsie sat. She kept her gloves on; she did not trust her hands.

He opened a file in front of him, glanced at a page, and then looked up at her with an expression that suggested he had already rehearsed this conversation in his head.

“Your letter states,” he began, “that you wish to query the particulars recorded regarding Private Thomas Barnett, service number – ”

“Tom,” Elsie said before she could stop herself. The word slipped out like a pulse. “He was called Tom.”

Mr Swithin paused, as if the familiar name had unsettled the formality. “Quite,” he said, and then, more softly, “Thomas, then.”

Elsie watched his pen hover. The nib trembled a little. It was ridiculous, that such a small tremor should matter, but her mind seized on it. He was not a machine. He could choose. That was the terrible hope of it.

“I understand you have concerns about the spelling of the name,” Mr Swithin said. “And about the classification.”

“Concerns,” Elsie repeated. The word tasted like paper. “It’s wrong.”

He drew in a breath through his nose, as though smelling the smoke. “Miss Barnett, the records are compiled from reports received in difficult circumstances. Errors – regrettable errors – do occur.”

“Regrettable,” she echoed, and heard her own voice sharpen. It was the same tone she had used with an overconfident surgeon once, when he had spoken of “a minor complication” and she had held the boy’s hand while he died. “It’s not a matter of regret. It’s a matter of what you’re saying about him. What you’re putting down for…” She caught herself, because the words wanted to run away with her, and she could not afford that. “For my mother.”

Mr Swithin’s eyes flicked to the file again. “There is no desire on anyone’s part to cause additional distress,” he said, which was the sort of sentence a man might say when distress had become a routine item on his desk. “However, there are procedures. Evidence is required. Statements.”

“I’ve brought what I can,” Elsie said.

He waited, hands folded, and she felt the weight in her pocket grow heavier, as if it were drawing her hand down to the truth whether she liked it or not.

“What is it you mean to offer, Miss Barnett?” he asked.

It was a simple question. A fair one, perhaps. Yet it struck her as intimate in a way nothing in this building had the right to be. Offer. As though she were bargaining.

Elsie took her hand out of her pocket and placed the compass on the desk between them.

The brass looked almost vulgar in the office’s grey light, too personal, too small, too stubbornly itself. The glass was scratched. Inside, the needle quivered and steadied, pointing to a north that did not care for paperwork.

Mr Swithin stared at it. His brows knit, not with contempt but with calculation. He did not touch it at first.

“A compass,” he said, as if naming it might keep it from becoming anything else.

“It was his,” Elsie replied. “He had it when he was a boy. Before he went. He took it with him.”

“How did you come by it?” Mr Swithin asked, and the question was carefully neutral, yet it held a hook.

Elsie’s mouth went dry. How indeed. A brown envelope through the post, no return address. Inside, the compass wrapped in newspaper and a slip of paper with only three words, written in a hand that shook: For his sister.

If she told the truth, she would be admitting that someone had broken a rule. If she lied, she would be doing what this building did every day: trading in convenient fictions.

“It came back,” she said at last, because it was the closest she could come to honesty without offering up a stranger’s neck to the guillotine of procedure.

Mr Swithin’s gaze lifted from the compass to her face. His eyes were not unkind. They were weary. He looked, for a moment, as though he might speak to her as one human being to another. Instead he cleared his throat and reached for the object with two fingers, as the clerk had handled her letter.

He turned it over. The needle trembled again.

“Miss Barnett,” he said, and his voice had changed, not quite softened but lowered, as if the room had become smaller. “Tell me something, if you will.”

Elsie’s heart gave a hard, stupid lurch. Nothing in this building ought to be personal. She did not want personal. Personal was how you got trapped.

“What?” she asked.

He hesitated, then looked at her with a curious steadiness, as though he were about to risk a kindness he could not later retract.

“When you were young,” Mr Swithin said, “was there an item you were… particularly attached to?”

The question landed oddly, like a stone thrown into the neat pond of the file. Elsie stared at him, not understanding. Her mind supplied absurd answers – her mother’s thimble, her father’s pipe, the ribbon she’d worn to school – anything but the thing pulsing between them like a second heart.

Mr Swithin continued, the colour rising faintly in his cheeks, as if he were embarrassed by his own departure from protocol.

“Something you could not bear to mislay,” he said. “Something you believed – foolishly or not – could set you right again. And,” he added, and now his eyes flicked down to the compass and back up, “what became of it?”

Elsie’s throat tightened until the air scraped through. She could have laughed. She could have cried. Instead she heard herself say, very quietly, “It became evidence.”

And, as she spoke, she understood that the story of the compass was not only Tom’s. It was hers now, whether she wanted it or not. North was north. The marvel of it. The cruelty of it.

The heavy oak door of Mr Swithin’s office clicked shut, leaving Elsie in the corridor with the sound of her own breathing. She hadn’t left the compass. She hadn’t been able to. When his hand had stretched out – fingers stained with the government’s black ink, ready to tag and file the only warm thing left of her brother – her own hand had snapped shut over the brass casing.

“I need proof, Miss Barnett,” he had said, his voice dropping to that weary, dusty register. “Provenance. A sworn statement from the finder. Otherwise, it is merely… sentimental property.”

Sentimental property. The phrase rattled in her head like shrapnel as she pushed back out into the Whitehall sleet.

The city had turned darker in the hour she’d been inside. The fog was rolling off the Thames, yellow and sulphurous, tasting of coal fires and the damp wool of a million greatcoats. She caught a motor-bus on the Strand, squeezing in between a woman with a basket of wet laundry and a man whose face was half-hidden by bandages. No one looked at him. That was the London way now: look at the pavement, look at your shoes, don’t look at the gaps where men used to be.

The bus groaned eastward, trundling past the City’s sober banks and into the tangled arteries of Whitechapel. Here, the victory bunting hung limp and grey, sooted by the railway lines.

Elsie got off at a corner that smelled of vinegar and frying onions. She checked the slip of paper in her purse – the return address from the brown envelope that had brought the compass home three weeks ago. 14a Brick Lane. c/o A. Khan.

The building was a narrow slice of brick squeezed between a bakery and a boarded-up glazier’s. The stairs inside were steep and dark, the banister sticky with damp. Elsie climbed to the second floor, her heart beating a hard, frantic rhythm against her ribs. She was not a woman who knocked on strangers’ doors; she was a woman who kept lists, who boiled bandages, who knew her place. But Tom was dead, and the compass was burning a hole in her pocket.

She knocked.

The door opened a crack, held by a chain. A dark eye regarded her, sharp and unblinking.

“I’m looking for A. Khan,” Elsie said. “About the parcel. The compass.”

The chain rattled and fell. The door opened to reveal a room that was less a home and more a workshop. Fabric was everywhere – bolts of cheap serge, piles of lining silk, half-finished waistcoats draped over chairs. In the centre, under the hiss of a gas lamp, sat a woman not much older than Elsie, with a tape measure round her neck and a mouth full of pins.

She took the pins out, placing them in a saucer with precise, fluid movements. “I’m Amira,” she said. Her accent was East End sharp, but beneath it lay a cadence that spoke of somewhere further, somewhere warmer. “You’re the sister, then. The Barnett girl.”

“Elsie.”

“Come in, Elsie. Shut the door. The draught costs money.”

Amira Khan cleared a chair by sweeping a pile of lining off it. She was small but formidable, her hands scarred from needle-pricks, her eyes carrying that same heavy, patient exhaustion Elsie saw in the mirror every morning.

“You got it, then,” Amira said, sitting back down at her machine. “I wasn’t sure the post would take it. Not with the address smudge like that.”

“You sent it.” Elsie stood by the fire, which was barely a glowing coal in the grate. “Mr Swithin – the man at the War Office – he says I need a statement. To prove it was Tom’s. To prove how it came to be… here.”

Amira picked up a piece of chalk and marked a line on a sleeve. “It came to be here because my Kasim brought it back. Before the flu took him.”

The silence that followed was thick enough to touch. The flu. It had swept through the tenements in November like a biblical wind, taking the ones the war had missed.

“Your husband?” Elsie asked.

“Brother. Labour Corps. He was unloading the stretchers at Boulogne. Said a lad pressed it into his hand. Delirious, likely. Said, ‘Keep me true north.’ Then he was gone.” Amira looked up, her gaze direct. “Kasim kept it. Reckoned it was lucky. Brought it home in his kit bag.”

Elsie’s hand went to her pocket. “Why did you send it to me? You could have sold it. Good brass.”

Amira laughed, a dry, short sound. “I thought on it. Three shillings, maybe four. Buy a lot of coal, four shillings.” She stopped, her face softening. “But I saw the scratching on the back. ‘T.B.’ And the village name. I thought, ‘There’s a woman somewhere looking at a door, waiting for that to walk through.’ We don’t sell ghosts in this house, love. We’ve enough of our own.”

She stood up and went to a small bureau, pulling out a sheet of paper and a bottle of ink. “You want a statement? I’ll write it. ‘I, Amira Khan, verify that this object was recovered from the person of Private Thomas Barnett…’” She looked at Elsie. “That what you need? To get his pension?”

“To get his name right,” Elsie said. “They have him down as ‘Bennett’. They have him down as ‘Died of Wounds’ when he… if he gave it to your brother at the clearing station, he was alive. He wasn’t missing. He didn’t desert.”

“Paperwork,” Amira muttered, dipping the pen. The scratch of the nib was loud in the room. “Men make wars, then they make paper to cover up the mess.”

She finished writing and blew on the ink. She handed the paper to Elsie. It was proof. It was the key to the lock Mr Swithin had put on the truth.

“There,” Amira said. “You take that to your man in Whitehall. You make him write the name proper.”

Elsie took the paper. It trembled in her hand. “Thank you.”

“Don’t thank me yet.” Amira sat back down, picking up her sewing. She looked at Elsie with a sudden, devastating clarity. “You know what they do with evidence, don’t you? Once they accept it?”

Elsie paused. “What?”

“They file it,” Amira said, pushing the needle through the tough serge. “My Kasim’s pay-book. His medal. I sent them in to get my widow’s shilling. Never saw them again. Stuck in a box in a basement in Kew, likely. Validated. Stamped. Gone.”

The cold of the room seemed to seep into Elsie’s marrow.

“If you give them that compass to prove he was who he was,” Amira said softly, not looking up, “you won’t get it back. Government property then. Part of the record.”

Elsie’s fingers curled around the brass in her pocket. The dent in the side where Tom had dropped it on the scullery floor. The way the needle swung, hunting for a north that was true, not just bureaucratic.

She looked at the paper in her hand – the justice her mother needed, the correction Tom deserved. Then she felt the weight of the compass – the only thing that still felt like holding his hand.

“I have to choose,” Elsie whispered.

Amira snapped a thread with her teeth. “We always do, love. The dead don’t care about spelling. They only care that we remember them. You have to decide how you remember. On a piece of government paper? Or in your pocket?”

Elsie stood there, the smells of the workshop – dust, iron, old wool – filling her nose, suspended between the Archive and the memory. The paper was justice. The compass was mercy. And Mr Swithin was waiting.

The walk back to Whitehall felt different. The sleet had hardened into something vicious, spitting against the windows of the cab Elsie had extravagantly, recklessly hailed. She sat in the leather darkness, the two objects – the paper statement and the brass compass – burning against her hip like opposing magnets.

When she entered the War Office again, the lamps were being lit. The yellow gaslight pushed weakly against the gloom of the high ceilings, casting long, wavering shadows that made the clerks look like underwater creatures. Mr Swithin was still there. Of course he was. Men like him did not leave until the ledger balanced.

She knocked and entered without waiting for the call.

Swithin looked up, spectacles catching the light, turning his eyes into blank, shining discs. A half-eaten sandwich sat on a piece of greaseproof paper by his elbow. He looked smaller than before, diminished by the afternoon’s long attrition of forms.

“Miss Barnett,” he said, and there was a flicker of – was it surprise? Or relief? – in his face. “I did not expect you to return today.”

“I have it,” Elsie said. She walked to the desk. She did not sit. The wooden chair she had occupied earlier felt like a trap now. “The statement. From the person who found it. With the date and the name.”

She laid Amira’s note on the blotter. Swithin picked it up, reading it with that same maddening, forensic slowness. He adjusted his glasses. He checked the signature against some invisible standard of veracity in his head.

“A. Khan,” he murmured. “And this… this confirms the item was in Private Barnett’s possession at the Clearing Station.”

“It confirms he was alive,” Elsie said, her voice hard. “It confirms he didn’t desert. He was lost in the system, Mr Swithin. But he wasn’t lost.”

Swithin sighed, a long exhale that seemed to deflate him. He took off his glasses and rubbed the bridge of his nose, leaving a small red mark. “It is… compelling,” he admitted. “With this, and the item itself – the serial number, if we can match it to a purchase or a gift – we could conceivably open a file for re-adjudication. The spelling error alone… yes. We could issue a correction.”

He looked up at her, his eyes naked and tired without the lenses. “It would mean surrender, of course. Of the item. Exhibit A, as it were. It must be tagged. Verified. Stamped.”

Stamped. Gone. Amira’s voice, dry as fabric shears.

Elsie put her hand in her pocket. Her fingers found the cold metal. She traced the scratch on the glass. She thought of Tom showing it to her in the kitchen, the way he had believed in it. It knows, Els.

If she gave it to Swithin, Tom became a corrected line in a book. A “Thomas Barnett” who died properly, spelt correctly, pensionable and tidy. But the compass would go into a box in a basement, cold and dark, its needle pointing north in the dark forever, with no one to see it. It would become a thing of the state.

If she kept it… Tom remained “Bennett” in the official world. A mistake. A question mark. But he would be in her pocket. He would be warm.

Swithin held out his hand, palm open. A bureaucrat’s gesture, waiting for the tax to be paid.

“The compass, Miss Barnett?”

Elsie looked at his hand. She looked at the statement on the desk – Amira’s bold, defiant handwriting.

“You asked me,” Elsie said slowly, “what I was attached to. What became of it.”

Swithin blinked. “I… yes. A moment of curiosity. Forgive me.”

“I was attached to the truth,” Elsie said. “I thought it was a solid thing. Like a brick. Or a compass.” She took the compass out of her pocket. The brass gleamed dully. Swithin’s hand twitched towards it.

Elsie closed her fingers around it tight, until her knuckles turned white.

“But the truth isn’t in your files, Mr Swithin. And it isn’t in this room.”

She reached out with her other hand – the empty one – and picked up Amira’s statement.

“Miss Barnett?” Swithin’s voice rose, alarmed. “What are you doing? That is – “

“Evidence,” Elsie said. “And you can’t have it.”

She ripped the paper in half. The sound was shocking in the quiet room, loud as a pistol crack. Swithin half-rose from his chair, mouth opening, but he didn’t speak. He just watched as she tore it again, and again, dropping the pieces onto his pristine blotter like confetti.

“My brother’s name was Tom Barnett,” Elsie said, and her voice was shaking now, but not with fear. With a terrible, soaring release. “He had a cowlick he couldn’t flatten and he laughed when he cheated at cards and he loved this compass because he thought it was magic. That is who he was. You can write what you like in your book. You can spell it how you please. It doesn’t touch him.”

She shoved the compass deep into her pocket.

“He’s mine,” she said. “Not yours. Not the Army’s. Mine.”

Swithin sank back into his chair. He looked at the torn paper. He looked at Elsie, standing there in her cheap coat, blazing with a sudden, fierce dignity that made the office feel small and shabby.

He picked up a fragment of the letter. He looked at it for a long time. Then, very carefully, he swept the pieces into his wastepaper basket.

He opened the file – the file that said “Bennett” – and picked up his pen. He hovered over the page. He looked at Elsie one last time.

“The registry is closed for the day,” Swithin said softly. “But… clerical errors are within my purview to correct. Informally. For the sake of… legibility.”

He scratched something out. He wrote something new in the margin. He blotted it carefully. He did not look at her as he closed the file.

“The pension,” he said to the air, “is automatic upon the correction of a name. No evidence is required for a spelling mistake. Good day, Miss Barnett.”

Elsie stared at him. He had given her the victory without taking the toll. He had chosen, for one minute, not to be a machine.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

“Go,” Swithin said, picking up his sandwich. “Before I remember the rules.”

Elsie turned and walked out. She walked down the corridor, past the clerks, past the lions, out into the Whitehall night. The snow had stopped. The air was clear and biting. Overhead, the stars were out, indifferent and beautiful.

She put her hand in her pocket. The compass was there. She didn’t need to look at it. She knew which way was north. She turned towards the river, towards the bridge, towards home.

On 18th January 1919, eight days after the events of this story, the Paris Peace Conference formally opened, bringing together diplomats from thirty-two nations to reshape the post-war world. While leaders debated borders and treaties, millions of families faced a more private administrative aftermath. The British Empire alone suffered over 1.1 million military deaths, with more than 500,000 men having no known grave, their identities lost to mud or bureaucracy. The sheer volume of casualties overwhelmed the War Office; pension files were often the only official record of a soldier’s existence. Tragically, over 60% of these service records were later destroyed by fire in 1940 during the Blitz, meaning that for many, personal keepsakes – like Elsie’s compass – became the sole surviving proof of a life lived. Today, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission continues to identify remains found on former battlefields, a century-long process of correcting the historical record one name at a time.

Bob Lynn | © 2026 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to midwife.mother.me. Cancel reply