Describe your most ideal day from beginning to end.

I: The Shape of Morning

Dunolly, Victoria – February, 1897

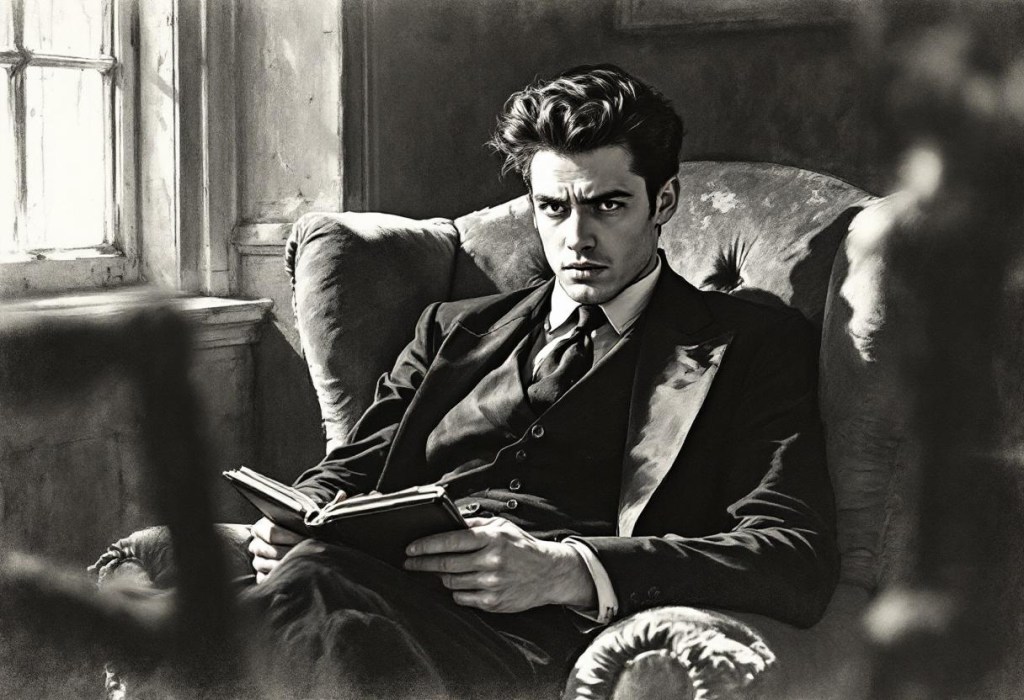

The young man from the Argus has the look of someone who has never had to scrape the red dust of the Mallee from his teeth. His suit is too sharp, his notebook too pristine, and his pencil poised with a kind of predatory eagerness that makes my old bones ache. He sits on the edge of Elizabeth’s good armchair, the velvet one we bought from the proceeds of the finding, though he likely doesn’t know that. He only knows the legend.

“Mr. Deason,” he says, leaning forward. He’s trying to be solemn, but I can see the hunger for a headline in his eyes. “To mark the anniversary, I’d like to ask something… unusual. Not just the facts of the weight or the depth. We have those. I want the man behind the gold.” He pauses for effect. “Describe your most ideal day, from beginning to end.”

I look past him, out the window where the afternoon light hits the gum trees. It’s a dry heat today, the kind that cracks the earth. It smells of eucalyptus oil and ancient dust. It smells exactly as it did twenty-eight years ago.

“My ideal day,” I repeat, the words rolling around my mouth like a pebble.

He nods, encouraging. “The day you’d live again, if you could.”

I close my eyes. He thinks he knows the answer. He thinks I will say the fifth of February, eighteen hundred and sixty-nine. He thinks the ideal day is the day the world changed. But memory is a trickster, boy. It doesn’t always hold tight to the gold; sometimes it clings to the dirt that hid it.

“You want the fifth,” I say softly. “You want the finding.”

“It was a Friday, wasn’t it?” he prompts.

“Aye,” I say, the old Cornish burr slipping back into my voice as it always does when I look backward. “A Friday. Though out at Bulldog Gully, the days didn’t have names. They only had weight.”

I settle back, letting the years fold away.

Bulldog Gully, Moliagul – Dawn, 5th February, 1869

The morning didn’t announce itself with trumpets. It came in grey and quiet, stealing through the gaps in the bark slabs of the hut. There was no premonition, no shiver in the blood to tell me that I was waking up a poor man for the very last time.

I lay there for a moment, listening to the bush breathe. The magpies were just starting their warbling, that liquid sound like water bubbling over stones, the only water you were likely to hear in this dry, thirsty country. Beside me, Elizabeth was deep in sleep, her breathing a soft rhythm against the silence. She looked tired, even in sleep. We were all tired. Seven years in the colony, chasing the colour from rush to rush, and the gold always seeming to stay one step ahead of us, like a ghost flitting through the ironbarks.

I swung my legs out of the cot, the dirt floor cool under my bare feet. I dressed in the dark – moleskin trousers stiff with yesterday’s sweat, the flannel shirt that had been patched more times than I could count. I didn’t wake her. There was no need. She’d be up soon enough to see to the little ones, to haul water and fight the dust that settled on everything we owned.

Outside, the air was still sharp with the night’s chill. I grabbed the water bag from the hook and stepped out.

Richard was already there.

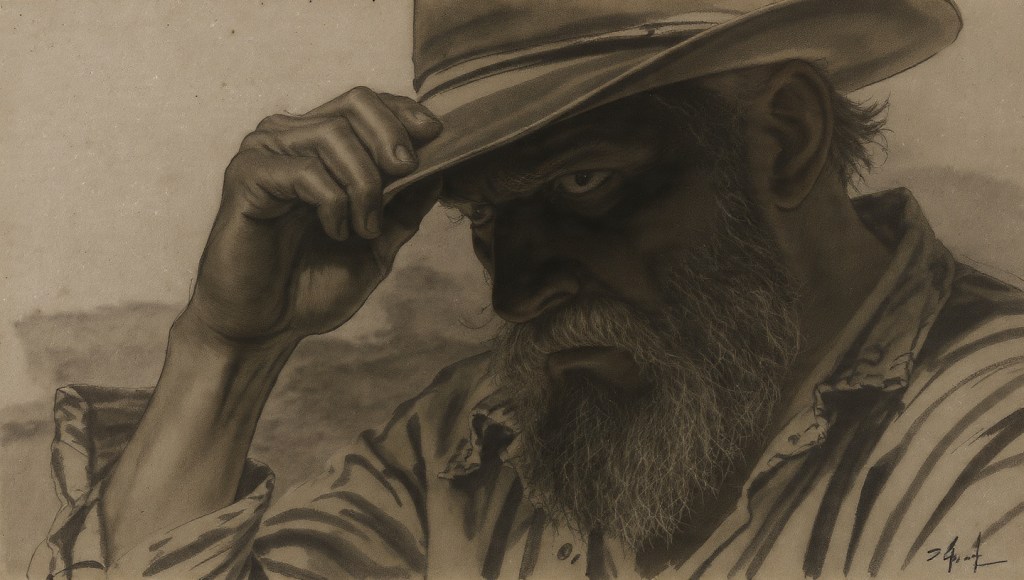

He was leaning against the windlass of our old shaft, rolling a smoke with those thick, capable fingers of his. Richard Oates. We’d come from the same scrap of Cornish coast, Penzance boys both, and we’d walked more miles in this upside-down land than I cared to remember.

“Mornin’, John,” he said. He didn’t look up, just licked the paper and sealed it.

“Mornin’, Richard.”

“Bit of a chill in it yet.”

“It’ll burn off,” I said. “Be a scorcher by noon.”

“Aye.”

That was the way of us. We didn’t need many words. When you’ve spent years sharing a tent, sharing a claim, sharing the crushing disappointment of a dry hole and the meagre joy of a few specks in the pan, you learn to speak in shorthand.

We walked down towards the gully, our boots crunching on the dry leaves. The sun was just starting to bleed over the horizon, painting the tops of the gums in fire. It’s a strange, violent beauty, this country possesses. Back home, the light is soft, filtered through sea mist. Here, it’s hard. It exposes everything.

We reached the spot we’d been working near the roots of an old box tree. It wasn’t a deep shaft; we were surfacing mostly, scraping away the topsoil in the hope of finding alluvial gold that had washed down over the centuries. It was unglamorous work. No deep leads, no engineering. Just a pick, a shovel, and a back willing to break.

“Reckon we clear the scrub round the far side today,” Richard said, eyeing the tree. “Ground looks promising.”

I nodded, spitting on my hands and rubbing them together. “Promising,” I echoed. “Ground’s been promising me a mansion for ten years, Dick. So far it’s given me a bark hut and a sore back.”

Richard chuckled, a low rumble in his chest. “You Cornish miserable sod. The colour’s there. I can smell it.”

“You smell sheep dung and dry grass,” I told him, picking up my pick.

He passed me the water bag. I took a long pull, the canvas tasting of earth and damp. The water was lukewarm, but it was wet. I wiped my mouth with the back of my hand.

“Right then,” I said.

I swung the pick. Thud. The sound of steel biting into hard-packed clay.

It was the most ordinary sound in the world. It was the sound of my life. Thud. Lift. Thud. Lift.

For the first hour, that was all there was. The sun climbed higher, stripping the chill from the air and replacing it with a heavy, pressing heat. The flies started to wake up, buzzing around our eyes and mouths, sticky and persistent. We worked in a rhythm, Richard shovelling what I loosened. We didn’t speak of fortune. We didn’t speak of the future.

I remember stopping to wipe the sweat from my brow, leaning on the handle of the pick. I looked at Richard. He was red-faced, his shirt clinging to his back. He looked up and caught my eye, and for a second, he just grinned. A tired, crooked grin that said, Here we are again, John. Two fools in a hole.

“What are you stopping for?” he asked. “The Queen isn’t coming to dig it for you.”

“Just admiring your ugly mug, Oates,” I said. “Wondering how a man gets so ugly without trying.”

“Takes practice,” he said, and tossed a shovelful of dirt aside. “Years of dedication.”

I laughed. It was a good laugh, light and easy.

That, I think now, sitting in this velvet chair with the journalist’s pencil scratching away – that was the moment. The ideal moment. The sun on my neck, the strength in my arms, and my best friend beside me, both of us broke as beggars but rich in the knowing of each other. There was hope in that hole, but it was a quiet hope. It was a safe hope. It hadn’t yet become the terrifying thing that was waiting for me three inches under the soil.

I hefted the pick again.

“One more go at this root,” I said, eyeing the gnarly wood of the box tree that was fouling my line. “Then we’ll have a smoke.”

“Right you are,” Richard said.

I raised the pick high, aiming for the hard clay packed tight around the tree’s base. I brought it down with all the force I had, intending to break the earth open.

The steel point hit the ground.

And it didn’t go thud.

It made a sound I had never heard before. A dull, solid, unyielding clunk. Not stone. Stone chips. Stone rings. This… this absorbed the blow. It felt dead in the handle, a shock travelling up my arms to my shoulders.

I frowned. “Hit a rock,” I muttered.

“Big one?” Richard asked, not looking up.

“Feels like ironstone,” I said. I shifted my feet, aiming a few inches to the left, trying to clear the obstruction so I could lever it out.

Clunk.

The same dead resistance. The same jar to the bone.

I stopped. The bush went quiet around me. Even the flies seemed to pause. I looked down at the reddish clay. There was nothing to see, just the scratch marks of the pick. But my hands… my hands were trembling.

I dropped to my knees.

“John?” Richard’s voice changed. “What is it?”

I didn’t answer. I couldn’t. I reached out with my bare hand and brushed away the loose dirt. I clawed at the hard-packed earth, my fingernails tearing. I cleared a patch the size of a saucer.

It wasn’t rock. It wasn’t ironstone.

It was yellow.

Not the bright, glittering yellow of fool’s gold, but a dull, buttery, heavy yellow that seemed to drink the sunlight.

I scraped further. It went on. Six inches. Twelve inches. I scrabbled frantically now, tearing at the roots, pushing the soil away. It didn’t end. It just kept going, a massive, slumbering thing that I had woken up.

I sat back on my heels, the breath leaving my lungs in a rush that sounded like a sob.

“Richard,” I whispered. My voice cracked. “Dick.”

He came over, peering into the hole. I saw the moment his brain registered what his eyes were seeing. I saw the colour drain from his face, leaving him pale beneath the sunburn. He dropped his shovel.

“Mother of God,” he breathed.

We stared at it. We didn’t touch it. We just stared. It was like looking at the sun without blinking.

“Is it…” Richard started, then stopped, afraid to say the word.

“Aye,” I said. “It is.”

And in that silence, under the gum trees of Bulldog Gully, the ideal day ended. The easy camaraderie, the comfortable struggle, the simple hope – it all vanished. In its place came a sudden, terrifying weight. I looked at the trees and saw not shelter, but hiding places for thieves. I looked at the track and saw not a road, but a threat.

I looked at Richard, and for the first time in twenty years, I didn’t see just my friend. I saw a witness.

“Cover it,” I hissed, grabbing the shovel. “Cover it up, man, before someone sees.”

And we began to bury what we had found, our movements jerky and fearful, two men suddenly prisoners of the very thing we had spent a lifetime seeking.

II: The Longest Afternoon

Bulldog Gully, Moliagul – Midday, 5th February, 1869

You might think, sitting there with your smooth hands and your city shoes, that discovering a fortune is a moment of pure, shouting joy. A moment where a man throws his hat in the air and dances a jig. But you’d be wrong.

Fear was the first thing. Fear, cold and hard as a nugget itself, settled right in the pit of my stomach.

We had covered her up – I say “her” because a thing that beautiful, that demanding, she felt like a living creature. We scraped the red dust back over that buttery curve until the ground looked innocent again. Just another patch of scrub near a box tree. But I knew. The knowledge burned a hole in my mind.

“John,” Richard whispered. He was standing too stiffly, his eyes darting toward the track where old Fagan usually walked his mule about this time. “What do we do? We can’t move it. Not in daylight.”

“We work,” I said, though my voice sounded strange to my own ears, thin and reedy. “We stand here and we work like we’ve found nothing but pennies. If we stop, they’ll look. If we run, they’ll follow.”

So we began the performance of our lives.

The sun climbed to its zenith, a white-hot coin nailed to the roof of the sky. The heat in the gully was oppressive, a physical weight that pressed down on our shoulders, but I barely felt it. I swung my pick at the barren earth a yard away from the treasure. Thud. Lift. Thud. Lift.

Every instinct in me screamed to fall on my knees, to claw that earth away again just to make sure she was still there, to embrace that cold metal. But I forced my arms to swing the pick.

“Don’t look at it,” I hissed at Richard. He was leaning on his shovel, staring at the patch of disturbed soil like a man hypnotised.

“It’s too big, John,” he muttered, not moving his lips, looking for all the world like he was contemplating the weather. “It’s too big to be real. Maybe the heat’s touched us. Maybe it’s just a fever dream.”

“If it’s a dream, it weighs two hundredweight,” I snapped. “Now dig, man. Dig like you’re hungry.”

The afternoon stretched out, agonising and slow. Time, which usually slipped away from us in the rhythm of labour, now hung suspended. I watched the shadow of the box tree. It seemed nailed to the ground, refusing to lengthen.

A group of Chinese diggers walked past on the upper ridge, their baskets swaying on bamboo poles. They were talking in that singing, high-pitched cadence of theirs. usually, I’d wave – I had no quarrel with them, they worked harder than any white man I knew – but today, my heart hammered against my ribs like a trapped bird. Walk on, I prayed. Don’t look down. Don’t see the guilt written on my face.

They passed. I let out a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding.

“How long till sundown?” Richard asked. It was the tenth time he’d asked in an hour.

“Long enough,” I said. “Keep your head down.”

The thirst came then – not just the dry mouth of a working day, but a parched, nervous thirst that made my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth. But I didn’t dare walk to the water bag. It was too far from the spot. I couldn’t leave that patch of earth unguarded, not even for ten paces.

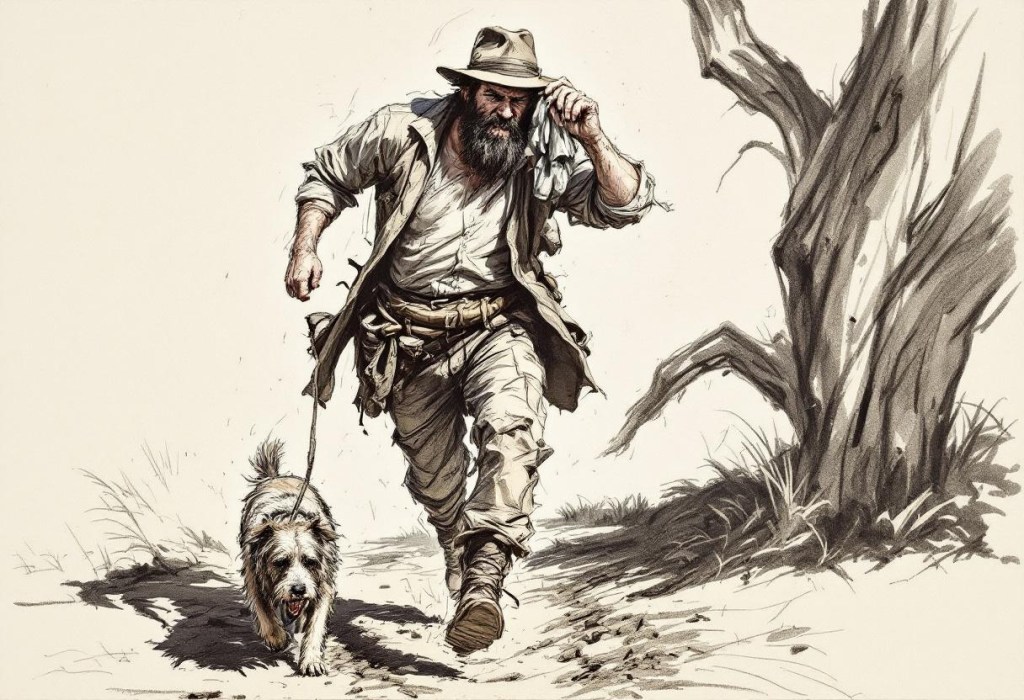

“Deason!”

The shout made me jump so hard I nearly dropped the pick. It was Bill Gorry, walking down the track with his dog. He was a loud, cheerful man, the kind who’d talk the leg off a pot-bellied stove. Any other day, I’d be glad of the distraction. Today, he looked like the devil himself coming to collect.

“Hot enough for you?” Gorry bellowed, wiping his forehead with a filthy rag. He stopped ten yards off. The dog, a scruffy terrier mix, trotted closer, sniffing at the ground. Sniffing near the roots. Sniffing near the spot.

“Aye, Bill,” I managed, stepping casually between the dog and the buried monster. “Hot enough to fry an egg on a shovel.”

“Found anything?” Gorry asked, leaning on a stump. He was in no hurry. He had all the time in the world.

Richard froze. I could see the panic rising in his eyes.

“Dust,” I lied. The word tasted of ash. “Just dust and aches, Bill. Same as yesterday. Same as tomorrow.”

“Ah, she’s a cruel mistress, the ground,” Gorry sympathised. He whistled to his dog. “Here, Bluey! Leave that root alone.”

The dog lifted its leg and pissed on the very earth that hid a king’s ransom. I watched the stream of urine darken the soil, and a hysterical laugh bubbled up in my throat. If you knew, little dog. If you only knew what you were pissing on.

“Well, best be off,” Gorry said, straightening up. “Hearing talk of a rush over near Berlin. Might try my luck there.”

“Good luck to you, Bill,” Richard croaked.

We watched him walk away, his whistle fading into the bush. When he was gone, Richard slumped against the tree, his legs giving out.

“I can’t do this, John,” he whispered. “My heart’s going like a stamp battery.”

“You have to,” I said. I looked at the sky. The shadows were finally, finally beginning to stretch. The harsh white light was mellowing to a deep, bruised gold. “Just a few more hours, Dick. Just hold on.”

As the sun dipped lower, the bush began to change. The kookaburras started their evening chorus, that mocking laughter echoing through the gums. Hoo-hoo-hoo-ha-ha-ha! They knew. The trees knew. The whole land seemed to be holding its breath, waiting for us to commit the theft.

Because that’s what it felt like. Not a discovery, but a theft. We were stealing this thing from the ancient earth. It didn’t belong to us. It belonged to the silence and the dark. And we were dragging it into the light of men, where it would be weighed and measured and melted down into sovereigns to buy velvet chairs and pocket watches.

I felt a sudden, sharp pang of loss. I looked at the undisturbed scrub around us, the wild, chaotic beauty of the gully. Tomorrow, everything would be different. We would be different. The men who swung picks for a living would be gone, replaced by men who owned things. Men who worried about banks and thieves.

“It’s time,” Richard said softly.

The sun had slipped behind the ridge. The light was failing fast, turning the world to violet and grey. The other miners had packed up; we could hear the distant sounds of camps being made, wood being chopped for fires, the smell of damper cooking. We were alone.

“Right,” I said. “Let’s get the bastard out.”

We fell to our knees. No picks now. We used our hands, clawing like animals. The soil was still warm. We swept it aside, revealing the dull gleam again. It seemed to have grown in the darkness. It looked like the back of a sleeping leviathan.

I got my hands under one end, Richard the other.

“On three,” I whispered. “One. Two. Three.”

We heaved.

The earth sucked at it, reluctant to let go. It groaned, a wet, sucking sound, and then it came free.

The weight of it was shocking. It pulled my shoulders down, straining the sinews of my back. It was heavy with density, heavy with value, heavy with fate. We stumbled, grunting, wrestling the mass of gold out of the hole and onto the canvas blanket we’d laid out.

We wrapped it up quickly, folding the dirty cloth over the gleam, hiding it away.

“Christ,” Richard panted, wiping his hands on his trousers. “How are we going to carry it?”

“We carry it,” I said, grabbing two corners of the blanket. “We carry it like it’s a dead body. Because if anyone sees it, that’s likely what we’ll be.”

We hoisted the load between us. It swung low, knocking against our knees. We began the walk back to the hut, moving through the gathering dark, stepping carefully over roots and stones. Every snap of a twig sounded like a pistol shot. Every rustle in the grass sounded like a footstep.

I looked up at the first stars pricking the indigo sky. They looked cold and distant, indifferent to the two fools stumbling through the scrub with a rock that could buy a town.

“Heavy,” Richard grunted.

“Aye,” I said. “Heavy.”

And I knew then, as the canvas cut into my fingers, that I would never be light again. The days of walking easy were done. We were carrying the future, and God help us, it was a burden.

III: The Weighing of Souls

The Hut, Moliagul – Night, 5th February, 1869

We reached the door of the hut with our lungs burning and our arms trembling like telegraph wires in a gale. The dogs barked – a sharp, accusatory sound – but we didn’t hush them. We didn’t have the breath for it.

“Open it,” I gasped, nodding at the door with my chin because my hands were fused to the canvas.

Richard kicked the slab door with his boot. It swung inward, spilling a rectangle of warm, yellow lamplight onto the dust.

Inside, the domestic scene was so normal it felt like a slap. Elizabeth was at the table, mending a pair of trousers. Richard’s wife was stirring a pot over the fire. They looked up, annoyed at the interruption, then startled by our faces. We must have looked like madmen – sweat-streaked, eyes wide, dragging a filthy bundle between us like grave robbers.

“John?” Elizabeth stood up, the needle glinting in her hand. “What on earth – “

“Clear the table,” I croaked.

“What?”

“Clear the table, woman! Now!”

I had never spoken to her like that. Not once. She didn’t argue. She saw the terror and the wildness in me. She swept the sewing basket and the tin plates onto the floor with a clatter.

“Up,” I grunted to Richard.

We heaved the bundle up. It hit the wood with a massive, groaning thud that shook the floorboards. The table legs creaked in protest.

For a moment, nobody moved. The only sound was the fire spitting and the harsh sawing of our breath. I reached out with a shaking hand and peeled back the dirty canvas.

The lamplight caught it.

It didn’t glitter. It glowed. It sat there, ugly and magnificent, a great lump of frozen fire. It was coated in red clay and black ironstone, but the gold – the sheer, impossible mass of it – shone through.

Elizabeth made a sound I will never forget. It wasn’t a scream. It was a soft, escaping whimper, like the air leaving a bellows. She put her hand to her mouth, her eyes huge.

“John,” she whispered. “Is it… is it real?”

“It’s real, Liz,” I said, and my legs finally gave out. I sank onto the bench, staring at it. “It’s as real as the devil.”

Richard was laughing now, a high, brittle sound that bordered on hysteria. He was slapping the table, shaking his head. “Look at it! Look at the bloody size of it!”

We didn’t keep it secret. We couldn’t. A thing like that demands an audience; it’s too big for four people to hold in their heads. We sent word to the neighbours – trusted men, men we’d starved alongside. Fagan came. The Forsters. A dozen others.

They crowded into our small hut until the air was thick with pipe smoke and the smell of unwashed bodies and awe. I remember the faces in the lamplight – weather-beaten, lined with worry, suddenly smoothed out by pure wonder. They touched it reverently. They hefted it, straining to lift one end.

“Seventy pounds if it’s an ounce,” old Fagan muttered, tears tracking through the dust on his cheeks. “My God, John. My God.”

“More,” I said. “More than a hundred, I reckon.”

We drank tea – strong, black tea, laced with the last of a bottle of rum someone produced. We toasted the Queen. We toasted the colony. We toasted the dirt.

I sat in the corner, watching them. My children had woken up, creeping out from behind the curtain. I saw my little one, barely walking, reach out a chubby hand to pat the cold metal. I watched Elizabeth. She wasn’t looking at the gold anymore. She was looking at me. And in her eyes, I saw a relief so profound it broke my heart – the knowledge that the patching, the skimping, the fear of the empty flour bin, was over.

But as I sat there, surrounded by the noise and the smoke and the congratulations, I felt a strange hollowing out inside me. The chase was done. The great “What If” that hangs over every miner’s head had been answered. And in the answering, it had taken something away. The hope was gone, replaced by the having. And the having was a heavy thing.

Dunolly, Victoria – February, 1897

The young journalist has stopped writing. He’s looking at me with a furrowed brow, his pencil hovering over his notebook. The silence in the parlour stretches out, thick and dusty.

“And then?” he prompts. ” The bank? The smelting? The amount?”

“You know the amount,” I say, my voice rasping a little. “Two thousand, two hundred and eighty-four ounces. Nine thousand, three hundred and eighty-one pounds. The London Chartered Bank paid it. They had to cut it on a blacksmith’s anvil just to weigh it.”

I wave my hand dismissively. “That’s all in the records, boy. That’s just arithmetic.”

“But surely,” he presses, “surely that was the happiest day of your life? The day you secured your legacy?”

I look down at my hands. They are spotted with age now, the knuckles swollen. They are not the hands that swung the pick that morning.

“You asked for my ideal day,” I say slowly.

I reach into my waistcoat pocket. My fingers close around the small object I keep there. It’s not gold. It’s a piece of white quartz, smooth and worthless. I picked it up years ago, before the Stranger, on a day when we found absolutely nothing.

“Richard Oates is dead these seven years,” I tell him. “The money is… well, money goes. Land is bought, houses are built, children grow. It flows like water.”

I look the boy in the eye.

“You want me to say the fifth of February was my ideal day. And perhaps, for the history books, it must be. It was the day the world noticed John Deason.”

I lean forward, lowering my voice.

“But if you ask me, in the quiet of the night… I wonder if my ideal day wasn’t the fourth of February.”

The journalist blinks. “The day before?”

“Aye. The day before.”

I look out the window again, seeing not the manicured garden of my old age, but the wild, scrubby bush of Moliagul.

“On the fourth,” I say softly, “Richard and I were young. We were strong. We had nothing but a pick, a shovel, and a friendship that hadn’t yet been weighed against a fortune. We woke up that morning with everything to hope for. We went to sleep that night dreaming of what might be.”

I rub the quartz with my thumb.

“The fifth gave me the answer, son. But the fourth… the fourth still had the question. And there is a special kind of joy in the question that the answer can never match.”

The journalist stares at me. He doesn’t understand. He can’t. He’s young, and he thinks the gold is the point of the story. He writes down 5th February 1869 in his notebook and underlines it twice.

“Thank you, Mr. Deason,” he says, closing the book. “A remarkable story.”

“Aye,” I say, closing my eyes. “Remarkable.”

He gathers his things and leaves. I sit alone in the velvet chair. The house is quiet. Elizabeth is gone now, too. The silence is heavy, but it is not the terrified silence of the gully. It is just the silence of an old man who has lived past his own legend.

I hold the piece of quartz to the light. It catches the sun, sparking with a humble, stony glimmer.

“Mornin’, Richard,” I whisper to the empty room. “Bit of a chill in it yet.”

And for a moment, just a moment, I am back there. The air is cold, the pick is heavy, and the ground beneath my feet is full of secrets I have not yet spoiled by finding.

On 5th February 1869, in Moliagul, Victoria, Cornish miners John Deason and Richard Oates discovered the “Welcome Stranger,” the largest alluvial gold nugget in recorded history. Weighing approximately 72 kilograms (net) and resting just three centimetres below the surface, the find occurred nearly two decades after the Victorian Gold Rush began in 1851. Because no local scales could bear its weight, the nugget was broken into three pieces on a blacksmith’s anvil and smelted into ingots, yielding £9,381 – a sum equivalent to millions in modern currency. Although the original object was destroyed, the discovery remains the peak of Australia’s 19th-century mining boom, which at its height produced one-third of the world’s gold supply.

Bob Lynn | © 2026 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to Bob Lynn Cancel reply