This interview is a dramatised reconstruction based on Matilda Joslyn Gage’s documented writings, correspondence, and historical record – not a transcript of an actual conversation, as Gage died in 1898. It employs historical empathy and creative storytelling to explore how she might have engaged with contemporary questions, grounded rigorously in evidence but imaginative in execution; readers are encouraged to seek out her actual writings for direct engagement with her voice.

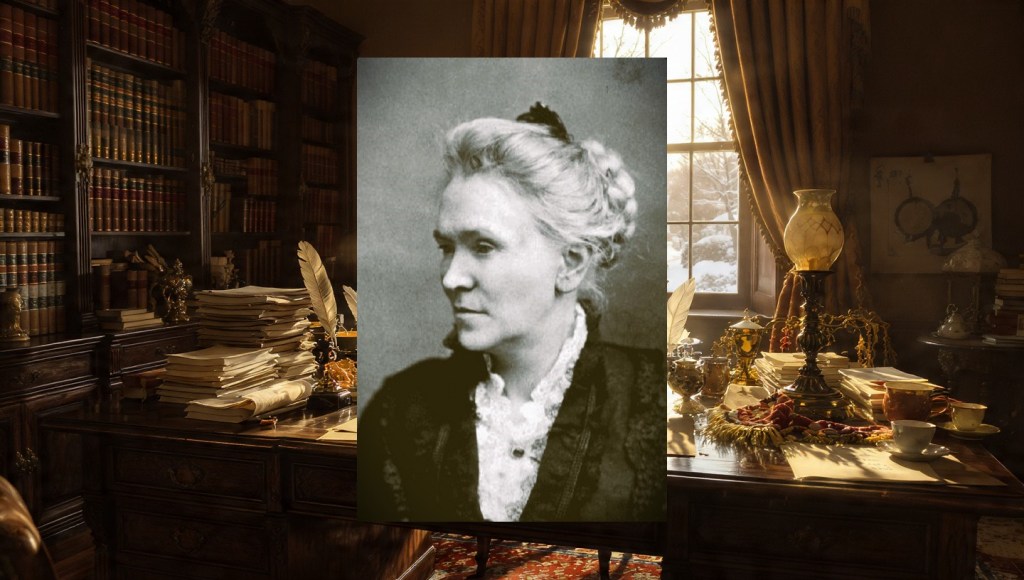

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–1898) was an American writer, activist, and pioneering historian whose research on women inventors exposed the mechanisms by which patriarchal institutions systematically appropriated female intellectual property. A co-founder of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association and author of the groundbreaking Woman as Inventor, she developed frameworks for understanding gender bias in scientific attribution more than a century before the “Matilda effect” was formally named. Yet despite co-authoring the definitive History of Woman Suffrage and producing rigorous historical scholarship, her contributions were marginalised by the very movement she helped establish, making her erasure itself a case study in how women’s intellectual work disappears.

Mrs. Gage, thank you for joining us on this peculiar occasion. I must confess that when I began researching your life, I found myself astonished – not at what you accomplished, but at how thoroughly your name had vanished from public memory. Here in 2026, more than a century after your death, we have finally begun the work you started: recovering women from historical obscurity. I’ve read your editorials, your pamphlets, your correspondence. Your voice is unmistakable – clear-eyed, uncompromising, often wickedly funny. I’m particularly compelled by your observation that “it is sometimes better to be a dead man than a live woman.” That sentiment seems to have aged poorly for patriarchy, and yet still resonates.

You flatter me with your recognition, though I confess I take greater satisfaction in the fact that the question itself – why women’s work disappears – has finally become worthy of serious inquiry in your time. When I wrote that particular observation, I was examining the laws that permitted a man to will his children to a guardian unrelated to their mother, entirely dispossessing her of maternal authority even after death. The irony was indeed the point. A dead man retained legal standing his widow did not possess whilst living. It was not wit for its own sake, but rather the distillation of injustice into its most absurd form, so that even casual readers might grasp what systematic deprivation looks like.

As for my erasure – I am far less surprised by it than you might imagine. I watched it occur in real time. When my positions became inconvenient to those who wished to make the suffrage movement more palatable to Christian conservatives and temperance advocates, I was transformed from colleague to extremist. The 1913 official repudiation of Woman, Church and State by the National American Woman Suffrage Association was not a bolt from the heavens; it was the completion of a project begun in 1890, when Susan and I parted ways over the NAWSA merger. They had to erase me to preserve their narrative. That is not surprising. It is, in fact, precisely how power operates.

Let me begin with what I believe is your most consequential contribution to what we now call the history and sociology of science: your documentation of women inventors. Your 1870 pamphlet Woman as Inventor appeared at a moment when the dominant narrative held that women simply lacked inventive capacity. You didn’t simply argue against this claim – you systematised the evidence of its falsehood. Walk me through your methodology. How did you approach this work?

The premise of my investigation was deceptively simple: if women lack inventive genius, where are the records proving this absence? The absence of women from the historical record is not evidence of their incapacity; it is evidence of institutional exclusion. But I needed to demonstrate this with particularity, not merely assert it.

I began with what I could verify through correspondence, patent records, and historical documentation. Sarah Mather invented the deep-sea telescope – a genuine innovation permitting observation of submarine phenomena previously inaccessible to human study. This was not a domestic trifle or a refinement of existing apparatus; it was an original solution to a problem of natural philosophy. Maggie Knight developed machinery for manufacturing satchel-bottom bags – a specific mechanical innovation that improved upon existing processes and could be quantified in terms of production efficiency. Barbara Uthmann’s invention of pillow lace involved the synthesis of artistic design with technical execution in textile production. Angelique du Coudray’s stuffed mannequin for the practice of midwifery was perhaps most remarkable: it was a pedagogical innovation, a tool that expanded access to instruction in obstetrical technique.

The second phase of my work examined the structural impediments preventing women from becoming inventors or securing recognition for their innovations. Here, the analysis became more subtle. I examined patent law directly. In the vast majority of American states – I can tell you with certainty it was every state without exception that permitted married women control of their earnings – a married woman held no right to the earnings from her own inventions. Should she be successful in obtaining a patent, the legal title and authority to commercialise that invention resided with her husband or, if she remained unmarried, with her father or other male guardian. This was not incidental to the patent system; it was foundational to it.

That’s a crucial distinction. You’re describing not discrimination within a system, but discrimination structuring the system itself.

Precisely. And there is an additional layer. Society actively discouraged women from pursuing mechanical education and from cultivating inventive ambitions. We discourage girls from understanding machinery, from dismantling and reconstructing mechanisms to observe their operation, from engaging in the trial-and-error experimentation that invention requires. Then, when no women emerge as inventors, we cite this absence as proof of natural incapacity.

Furthermore, I documented cases where women inventors deliberately concealed their authorship by patenting under masculine names – those of husbands, brothers, fathers. They did this not from modesty, but from rational calculation: a woman’s patent would be treated with scepticism, was more vulnerable to legal challenge, and would invite ridicule from the scientific and commercial establishments. The loss of credit was the cost of protection.

Your claim about Catherine Greene inventing the cotton gin instead of Eli Whitney was particularly controversial. That assertion remains debated by historians. Can you articulate your evidence?

I will be candid with you: I relied upon oral testimony and family correspondence that I believed credible at the time. Greene’s family asserted her role in the innovation; contemporary accounts mentioned her active participation in the workshop where Whitney developed the apparatus. But I will acknowledge – and this is not easy to admit – that my certainty exceeded my evidence. I was so persuaded by the pattern I had identified that I moved too readily from suggestion to assertion. This was a failing in my scholarly practice, and I own it.

What I maintain with absolute conviction is that Whitney’s story as told is incomplete, and that the circumstances of women’s exclusion from credit made such omissions predictable and systematic. Whether Greene deserves full credit, partial credit, or some role yet to be precisely determined by historians with access to documentation I did not possess, the principle I was establishing remains sound: women’s contributions to technological innovation have been systematically erased, and this erasure is the result of institutional structures, not natural genius differentials.

I want to move deeper into one specific analytical framework you developed – what we might call the structural anatomy of how women’s inventive work disappears. You identified at least four distinct mechanisms. Let me ask you to walk through these as though you were explaining them to a fellow scholar of natural philosophy who understands mechanisms, systems, and the propagation of error through institutional processes.

Consider the problem as a series of interlocking mechanisms, each one independently capable of producing erasure, but far more devastating in combination.

First: The Legal-Property Mechanism. Under coverture – the legal doctrine that marriage renders a wife the property of her husband – a woman cannot hold title to intellectual property she creates. The patent she obtains is legally hers, yet she possesses no authority to commercialise it, modify it, license it, or receive compensation from its exploitation. Her husband holds these rights. Should she predecease him, the patent passes to his estate, not to her children or heirs. This creates a peculiar situation: her invention is legally attributed to her, yet all authority over its use resides elsewhere. In practice, this meant that women inventors frequently watched their creations modified, commercialised, or claimed by others who possessed legal standing to do so.

Second: The Educational Exclusion Mechanism. To invent in the mechanical arts requires familiarity with machinery, mathematics of a particular sort, and access to tools and workshops. Young men received such education as a matter of course. Young women of respectable families were actively prevented from acquiring it. Mechanical training was considered vulgar, unsuitable to feminine accomplishment, potentially corrupting to delicate constitutions. I knew brilliant women – women capable of the most sophisticated mathematical reasoning – who were forbidden from entering workshops because their presence was deemed improper. This created a plausible appearance that women lacked the technical knowledge necessary for invention. In reality, we lacked the permission and access to acquire such knowledge.

Third: The Attribution-Uncertainty Mechanism. When a woman produces an invention within a domestic or familial context – working alongside a husband, father, or brother – the contribution becomes obscured. Who precisely conceived the innovation? Who executed it? Who refined it? In a household workshop, this may be genuinely difficult to determine. But the institutional practice has been to attribute such innovations to the male household member, on the assumption that technical capacity naturally resides with him. This assumption is embedded in how we write histories, how we conduct interviews, how we evaluate patent applications. When doubt exists, institutional practice resolves it in favour of the male claimant. Over time, this produces a historical record in which ambiguous cases are systematically misattributed.

Fourth: The Social-Perception Mechanism. Women who pursue technical innovation face active discouragement and ridicule. The woman inventor is subjected to mockery – she is unfeminine, unsuitable, attempting to transcend her natural sphere. This social pressure operates as a form of suppression. Young women with inventive inclinations, observing the social costs borne by those who pursue such ambitions, suppress their own talents rather than face ostracism. Thus society produces the very incapacity it claims to observe. We refuse education, we make innovation socially costly, we systematically deny credit – and then we marvel that women do not become inventors.

These four mechanisms operate independently but also reinforce one another. A woman denied mechanical education cannot develop the expertise to produce significant innovations. Should she somehow overcome this barrier, legal structures prevent her from controlling her creation. If her contribution is ambiguous, institutional practice misattributes it. And should she persist despite social ridicule and legal disadvantage, her success makes her exceptional rather than representative, allowing the larger pattern of exclusion to persist as though it reflects natural reality rather than institutional design.

That’s a remarkably elegant analysis of how systems produce outcomes that appear to confirm their own premises.

Indeed. This is what I meant when I wrote that “the pen is mightier than the sword” – understanding how systems operate is the first step to challenging their legitimacy. Once you see the mechanisms clearly, the appearance of natural difference collapses. What remains is undeniable: institutional choice, not natural capacity, determines whether women’s inventive work is recognised or erased.

I must ask about your time among the Iroquois – this is perhaps the least understood dimension of your work. You were initiated into the Wolf Clan and given the name Karonienhawi, “she who holds the sky.” This was not honorary; you were admitted to the Iroquois Council of Matrons. How did this experience shape your understanding of political organisation and women’s power?

I arrived among the Iroquois with assumptions, as one does. I believed I was studying a “matriarchal” society in the abstract – a theoretical model demonstrating that female authority was possible. What I encountered was far more specific and consequential.

The Iroquois Confederacy is organised upon principles of descent through the female line. Property passes from mother to daughter. A woman retains authority over her own labour and its fruits. When a marriage dissolves, children remain with the mother; a man leaves his wife’s household and returns to his own mother’s dwelling. The fundamental economic unit is the female-headed household, though men contribute labour and authority.

But here is what is most crucial for your modern understanding: this is not merely a domestic arrangement. The political authority of the Confederacy flows through the same channels. The Council of Matrons selects and removes the male sachems – the civil leaders. If a sachem proves corrupt or incompetent, the Council can remove him. Women do not serve as sachems themselves in the traditional structure, but the authority that holds sachems accountable is female authority. Do you see the distinction? The formal positions of public leadership are held by men, yet the power that legitimates and can revoke that leadership is female.

So women exercised power through institutional design rather than through personal charisma or individual achievement.

Precisely. And this was a revelation to me. I had spent decades arguing that women deserved political authority as a natural right. The Iroquois demonstrated something more subtle: how women’s authority could be structurally embedded. It is not that individual Iroquois women possessed greater natural capacity for leadership – it is that their social and economic system created conditions in which female authority was not merely possible but necessary and institutionalised.

When the Council of Matrons admitted me to the Wolf Clan and gave me the name Karonienhaki, I understood this not as symbolic honour but as recognition that I comprehended something of their system. The name itself – “she who holds the sky” – was not poetic whimsy. It carried responsibility. It acknowledged that I had grasped the principle that female authority is not exceptional; it is foundational.

This experience transformed my understanding of what I was arguing for in America. I was not arguing for women to enter a male-designed system and claim their share of authority within it. I was arguing for the redesign of the system itself, so that female authority – economic, political, and intellectual – became structurally embedded, as it was among the Iroquois.

Yet your analysis of Iroquois society as fundamentally matriarchal has been contested by modern anthropologists. Some argue that your interpretation overstated female authority or romanticised their role. How do you respond?

I respond by noting that those who contest my analysis have rarely spent months living among the Iroquois, observing directly how authority operated. I made observations grounded in participation and testimony. If modern scholarship has more precise instruments for measuring political authority, I welcome that refinement. But I will not accept criticism from those who have merely read about the Iroquois in the comfort of their libraries.

That said, I will concede that I may have been too eager to find in Iroquois society a perfect model for what I was arguing. There are complexities I did not fully examine – the specific roles of women in warfare, for instance, or the degree to which certain female authorities were theoretically superior but practically constrained. The danger of using another culture as a political example is that one can project one’s own aspirations onto it.

What I maintain is this: the Iroquois demonstrated that female authority, economic autonomy, and political power are not natural impossibilities. They are culturally contingent arrangements. That recognition remains valuable, even if subsequent scholarship reveals nuances I missed.

Your 1893 work Woman, Church and State was extraordinary – but also controversial enough to be banned under the Comstock laws and officially repudiated by the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1913. You argued that Christianity was not incidentally oppressive to women but fundamentally structured around their subordination. Walk me through the logic of that argument. How did you arrive at such a controversial position?

I did not arrive at this position through theological speculation. I arrived at it through historical analysis. I examined centuries of church doctrine, canon law, and practice. I asked: what does the institutional church teach about women? What legal and social structures does it create? What justifications does it offer for those structures?

The answer that emerged from this examination was not comforting. The church teaches that woman was created as a subordinate being – created from man’s rib, intended as his helper, bearing responsibility for humanity’s fall from grace through her susceptibility to temptation. This is not incidental theology; it is foundational. From this doctrine flows everything else: the exclusion of women from priesthood, the insistence on female obedience within marriage and family, the control of female sexuality through shame and moral regulation, the restriction of women’s education and participation in intellectual life.

Furthermore, I traced how the church used this theological framework to influence secular law. Marriage law was ecclesiastical law. The dissolution of marriage required ecclesiastical permission – which women could not obtain on grounds that men could. The church’s control over education meant that women were excluded from university instruction and intellectual formation. The church’s authority over moral questions meant that women’s reproduction, sexuality, and bodily autonomy were governed by religious doctrine filtered through male ecclesiastical authority.

Now, here is where my analysis becomes most controversial: I argued that this was not accidental or susceptible to reform within the church’s framework. The subordination of women is necessary to Christian theology as historically developed. To genuinely liberate women requires challenging not merely individual church practices but the theological foundations themselves. This is why conservative suffragists found my position so threatening. They wished to reform women’s civil status while maintaining their religious subordination. They wanted the vote without challenging the church’s teaching about female inferiority.

That puts you in direct conflict with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and figures like Frances Willard, who believed women’s votes would serve Christian moral purposes.

Precisely. And I found their position incoherent. You cannot argue that women deserve authority in the political sphere based on their superior moral nature – a nature that the church insists they do not possess. The church teaches women’s moral inferiority, and the WCTU responded by insisting that women’s moral superiority qualified them for political authority. This is contradiction masquerading as strategy.

I argued for something far more radical: women deserve political authority as a natural right, not because we are morally superior, not because we will implement Christian temperance, but because we are human beings capable of self-governance. The moment you anchor women’s rights in moral superiority, you make those rights contingent. Should women behave in ways deemed morally inferior, the justification for their authority evaporates.

Your analysis of witch hunts was particularly powerful. You reframed them not as aberrations but as systematic campaigns against educated women who threatened patriarchal authority. But you also used what many scholars consider inflated numbers of victims – sometimes citing figures that modern historians argue are exaggerated.

I used the numerical evidence available to me, and I acknowledge that some of those figures have been questioned by subsequent historians. But I will say this: even if the numbers were somewhat lower than I cited, the fundamental truth remains. Educated women – women who understood herbalism, who practiced midwifery, who challenged male authority – were disproportionately accused and executed. The witch hunts were not random persecution; they were targeted campaigns against female knowledge and female power.

My error, if I am to be candid, was in allowing passion to outpace precision. I was so persuaded by the pattern – that elderly women, that educated women, that women who challenged male authority bore disproportionate risk – that I may have argued from a position of greater certainty than my evidence warranted. This is a failing I acknowledge. The historian’s task is to establish facts with precision, not to deploy whatever numbers serve one’s argument.

What I should have said more carefully is this: proportionally, women bore a far higher rate of accusation and execution than men, and among those accused, certain categories of women – the elderly, the unmarried, the knowledgeable about medicine and herbs – were particularly vulnerable. The systematic nature of this persecution is evident in these patterns, even if the precise absolute numbers remain uncertain.

Do you regret the anti-religious positions that cost you institutional support?

Not for a moment. The cost was real – I was marginalised, my work was repudiated, my name was erased from suffrage histories. But what was the alternative? To remain silent about the church’s role in women’s oppression? To accept that liberation could occur while women remained theologically subordinate? To join forces with conservatives who understood women’s rights as contingent on Christian moral purposes?

I was sixty-four years old when I founded the Woman’s National Liberal Union. I was well aware that this would be the final chapter of my public work. I was well aware that the conservative faction would distance themselves from me. But I could not compromise on this point. The church’s fundamental hostility to women’s autonomy is not a bug that can be fixed; it is a feature of Christian theology as historically developed. Any women’s movement that does not confront this directly will ultimately fail to achieve genuine liberation.

Whether I was right about this – history will judge. But I could not have done otherwise without betraying everything I believed.

In 1890, when the National Woman Suffrage Association merged with the American Woman Suffrage Association to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association, you and Elizabeth Cady Stanton opposed this merger and founded the Woman’s National Liberal Union instead. From a strategic perspective, this split looks like a catastrophic error – you isolated yourself from the mainstream movement at precisely the moment it was achieving greater political power. How do you respond to that critique?

You must understand what that merger represented. It was not a neutral organisational consolidation. It was a capture. Conservative suffragists – women devoted to Christian moral reform and temperance, women who believed that women’s votes would achieve religious political goals – gained control of the unified organisation. The price of their participation in the suffrage movement was the narrowing of its scope to a single issue: securing the vote.

Susan B. Anthony believed this was acceptable. She believed that once women had the vote, all other reforms would follow. I disagreed then, and history has borne out my scepticism. Women gained the vote in 1920. Yet did this automatically secure women’s reproductive autonomy? No. Did it immediately reform marriage law or secure women’s economic independence? No. Did it challenge the church’s authority over women’s moral and sexual regulation? No. The single-issue focus meant that these broader questions remained unaddressed.

Furthermore, the merger required the new organisation to distance itself from positions on church-state separation, on radical economic reform, on Native American sovereignty. The conservative faction demanded respectability above all else. They demanded that suffragism become compatible with Christian morality and conservative social reform.

But didn’t the split you chose guarantee your marginalisation?

Of course it did. And I understood this perfectly well. But what was the alternative? To remain silent? To accept the narrowing of the movement’s vision? To compromise on the fundamental question of whether women deserved autonomy as a natural right or merely as an instrumental good serving other political purposes?

The Woman’s National Liberal Union was smaller, less influential, less successful in immediate political terms. But it preserved something essential: the principle that women’s liberation requires challenging not merely electoral exclusion but the entire architecture of patriarchal authority – religious, legal, economic, intellectual.

I chose to be right over being vindicated by history. And I accept that this choice meant obscurity. That is not a failure; that is a price I was willing to pay.

Do you think you were wrong to make that choice?

I think I was right about the principle, and I accept that the tactical cost was real. If I had remained within the mainstream movement, I might have influenced its direction more effectively. Perhaps I could have prevented some of the conservatism that came to dominate. Or perhaps I would have been forced to compromise so greatly that I would have betrayed the very principles I believed essential.

The question of whether one should work within a compromised system seeking to reform it from within, or whether one should exit the system and preserve radical principles outside it – this is a question I have not fully resolved even now. Both positions have merit and costs. I chose the latter path, and I believe it was the only choice consistent with my convictions. Whether it was strategically superior – I cannot say with certainty. But I could not have lived with myself choosing otherwise.

It must be strange to hear that in 1993, nearly a century after your death, a scientific historian named Margaret W. Rossiter coined the term “Matilda effect” specifically to describe the phenomenon you documented – the systematic denial of women’s credit for scientific work. The “Matilda effect” is now standard terminology in the history of science. How do you feel about having your name attached to this concept?

I am grateful that the principle I attempted to illuminate has been recognised and formalised. That scholars use my name to describe this phenomenon is an honour I did not expect to receive, particularly after the official repudiation of my work. It is ironic – and fitting – that the very erasure I documented became itself a case study of the phenomenon I was describing.

But I am careful not to celebrate this recognition too enthusiastically. The naming of an effect after me does not change the fundamental fact: the barriers I identified in 1870 persist in 2026. Women remain dramatically underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Women scientists continue to receive less credit for their work than objective examination would suggest they deserve. The effect persists. Naming it does not eliminate it.

What I hope is that by identifying this phenomenon, by tracing its structural sources rather than attributing it to individual prejudice or natural capacity differences, contemporary scholars and scientists can address it more effectively than my generation could. The fact that women are now permitted to attend universities, to pursue scientific training, to hold academic positions – these are genuine advances. But the cultural devaluation of women’s intellectual contributions persists, albeit in somewhat different forms.

What would you tell a young woman today considering a career in science or invention?

I would tell her three things. First, the barriers she encounters are real and structural, not evidence of her incapacity. When she finds that her work is attributed to colleagues, when her ideas are credited to men, when her contributions are minimised – this is not because she is insufficiently talented. It is because institutions are designed to produce exactly this outcome. Understanding this intellectually is essential, because it prevents her from internalising the devaluation as deserved.

Second, I would tell her to document her work meticulously. Keep detailed records. Ensure that there is a paper trail that cannot be erased. Publish under her own name, not under a husband’s or a supervisor’s. Fight for attribution not out of personal vanity but because the historical record matters. The work of women scientists will be lost to history if women themselves do not insist on accountability and recognition.

Third, I would tell her to think deeply about what she is trying to accomplish. Is she seeking permission from institutions that may never grant it? Or is she pursuing knowledge and innovation because she believes these pursuits are valuable in themselves? Because if you are waiting for institutional validation, you may wait your entire life. But if you are committed to the work itself, then institutional recognition, when it comes, is a pleasant surprise rather than a prerequisite.

You’ve been critical of the strategic narrowing of the suffrage movement – the choice to focus exclusively on the vote rather than broader social transformation. Yet we live in an era where movements are constantly navigating the tension between radicalism and pragmatism, between ideological purity and tactical effectiveness. What guidance would you offer to contemporary activists facing these choices?

This is where I must be honest about the limits of my own wisdom. I made a choice that felt right to me, but I cannot claim it was strategically optimal. The women who kept working within the mainstream movement, who accepted the compromise on church-state questions, who narrowed the focus to electoral rights – they succeeded in securing the vote. Their approach was effective, even if it was not transformative.

What I would say is this: be clear about what you are compromising and at what cost. Do not tell yourselves that you are preserving your radical vision while accepting conservative alliances. Own the compromise directly. Say: “We are prioritising this specific goal, and we are accepting these constraints because we believe it will advance our immediate objective.” Do not pretend that the compromise is temporary or that you will address other issues later. Once you establish an organisation around a narrow mandate, it is remarkably difficult to expand that mandate.

Conversely, do not accept the argument that pragmatism requires abandoning all principle. The women who told me I was damaging the movement by raising questions about church authority, about women’s reproductive autonomy, about indigenous sovereignty – they were wrong. These were not distractions from women’s suffrage; they were expressions of what women’s suffrage meant. The question of what women would do with political power, what vision of society they were working toward – these questions were not peripheral. They were central.

My suggestion is this: be honest with yourselves about what you believe should be true. Build movements that embody those beliefs as directly as possible. Accept that this will narrow your coalition. Accept that it will make victory slower and less certain. But know what you are building and why. Do not accept organisational forms that betray your principles in the name of pragmatism. If you do, you may win tactical victories that leave the fundamental architecture of oppression intact.

The Wikipedia article about you has been viewed millions of times. There are academic centres dedicated to your work. Your foundation has been carefully preserved in Fayetteville. In some sense, you are being remembered and recognised more thoroughly in 2026 than you were during much of your lifetime. How do you feel about this belated recognition?

I confess I find it difficult to process. During my lifetime, I was acutely aware that my contributions were being minimised, my positions characterised as extreme, my name increasingly absent from the narratives being written about the movement I helped found. I made peace with that erasure. I accepted that obscurity might be the price of principle.

To learn that I am being recovered, that scholars are examining my work, that my name is attached to a scientific principle – this is gratifying. But I also recognise the irony. The recognition arrives long after I can influence the work I was attempting to do. I cannot engage in the scholarly debates about my interpretations of Iroquois society or my analysis of women inventors. I cannot refine my arguments or correct my errors. I am a historical figure rather than a living interlocutor.

What I hope is that this recovery of my work leads not merely to biographical interest but to substantive engagement with the principles I was attempting to establish. Do not simply honour Matilda Joslyn Gage as an eccentric historical figure. Engage seriously with my arguments about institutional structure, about the interconnection of different forms of oppression, about the necessity of challenging fundamental assumptions rather than merely reforming surface practices.

And I would urge contemporary scholars: do not make me into a saint or a perfect figure. I made errors. My analysis of Catherine Greene and the cotton gin went beyond what my evidence supported. My interpretations of Iroquois society may have been romanticised in certain respects. I was not infallible. But the fundamental principles I was pursuing – that women’s erasure from history and from intellectual recognition is the result of institutional structures, not natural capacity; that liberation requires addressing these structures directly; that women’s intellectual work must be documented and credited – these principles remain sound.

Do with my work what I attempted to do with the work of women inventors: recognise the genuine contributions, examine them rigorously, acknowledge the limitations and errors, and then ask what we can learn that remains applicable and urgent for your own moment.

Your son-in-law L. Frank Baum wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and scholars have argued that your political influence is evident in that work – particularly in the character of Dorothy, who appears as a powerful young woman making her own decisions. Do you take satisfaction in that influence?

I did not approve of the match between Maud and Frank. I thought he was beneath her – a struggling actor and playwright with no established career. But Maud was headstrong, and I had spent my entire life arguing that women should make their own decisions. I could not reasonably object when my own daughter exercised that independence.

Frank came to respect my work and my convictions. The Wizard of Oz does reflect, I believe, certain principles I held dear: that a young woman can be both powerful and good, that her agency matters, that she can solve problems through her own wit and courage. Whether this amounts to direct political influence or merely reflects the intellectual atmosphere in which Frank was raised – I cannot say with certainty. But I am satisfied that the work embodies values I care about.

As we near the end of our conversation, I want to ask you something more personal. You spent nearly fifty years engaged in activism, scholarship, and journalism. You were systematically marginalised by the movement you helped establish. Your work was repudiated by mainstream institutions. And yet you seem to have maintained conviction and even humour about it all. What sustained you?

Two things, I think. First, the absolute conviction that I was right about the fundamental analysis. Not right in every detail – as I’ve acknowledged, some of my historical claims required more evidence than I possessed. But right about the basic truth: that women’s subordination is institutionally produced, not naturally ordained; that the church and the law are central mechanisms of that subordination; that women are capable of intellectual and creative work equal to men’s but are systematically denied credit and recognition; that liberation requires addressing these structures directly rather than merely accepting women into existing systems designed around male authority.

This conviction was not arrogance. It was supported by historical research, by direct observation, by careful analysis. I could defend every major position I took with evidence and argument. That gave me confidence to maintain my positions even when they were unpopular.

Second, I was sustained by the work itself. The act of research, of writing, of attempting to communicate truths I believed essential – this was meaningful regardless of whether anyone was listening. I did not require institutional validation to make the work valuable to me. This is a luxury I acknowledge – I had a husband who supported my work, a family who did not entirely oppose it, the education and health to pursue intellectual labour for decades. Not all women have these advantages. But given that I possessed them, I was determined to use them in service of something I believed mattered.

And I will say this: I was wrong to assume my work would be forgotten entirely. I thought I would be erased completely, that the Woman’s National Liberal Union would leave no trace, that my books would disappear into obscurity. The fact that scholars are still engaging with my ideas, still finding them relevant and provocative, still using my name to describe scientific phenomena – this suggests that truth-telling has a longevity that hostility and repudiation cannot entirely destroy.

Any final message for the readers who will encounter this conversation?

Yes. Read carefully. Question authority, including my own. Examine the structures that produce inequality, not merely the individual prejudices of particular people. Insist on credit for your work. Document it meticulously. Challenge institutions that deny women – and other excluded groups – recognition and power. And understand that winning a single right – the vote, the right to own property, the right to education – is not the same as achieving liberation. Each victory requires asking: what remains unaddressed? What institutional structures still require transformation?

The work is not finished. It may never be finished. But that is not cause for despair. It is cause for continued commitment to the principles that matter: justice, autonomy, and the recognition of women’s intellectual and creative capacity as equal to men’s in every respect.

And perhaps – do not be entirely discouraged by institutional opposition. Institutions may repudiate your work, but ideas have a peculiar persistence. They resurface. They are recovered. They prove more durable than the institutions that oppose them. The pen, as I wrote, is mightier than the sword. And the written record, once created, is remarkably difficult to erase permanently.

Questions from Our Community

Since the publication of our interview with Matilda Joslyn Gage, we have received an overwhelming response from readers, scholars, activists, and practitioners across disciplines and continents. What began as curiosity about a historical figure has evolved into something more profound: a genuine conversation, mediated through time, between those working on contemporary problems and a woman who spent her lifetime articulating the frameworks through which we now understand gender, power, and institutional change.

The questions below represent five carefully selected letters and emails from our growing community. Each comes from someone working at the intersection of Gage’s multiple areas of expertise – feminist theory, legal scholarship, the history of science, anthropology, and social movement strategy. These are not casual inquiries but substantive engagements with the deepest tensions in Gage’s work: the relationship between principle and pragmatism, the ethics of cross-cultural research, the question of whether legal reform is sufficient to address cultural devaluation, and the philosophical foundations of rights claims themselves.

What emerges from these questions is a portrait of Gage’s enduring relevance – not as a historical monument to be admired from a distance, but as an intellectual interlocutor whose unresolved tensions remain live questions for those attempting their own work of transformation. These are the concerns of a Belgian science communicator navigating persistent gender gaps in patent filing despite legal equality; a Swedish historian asking whether narrow victories disable broader change; an Icelandic anthropologist wrestling with the ethics of cross-cultural engagement; a Brazilian labour advocate questioning the philosophical coherence of natural rights language; and a Latvian scholar of movements wondering whether different organisational choices could have altered historical trajectories.

In Gage’s responses to these questions, we find not final answers but invitations to think more rigorously about the problems we face. She had the advantage – and the burden – of lifetime commitment to these questions. Those who follow her path today would do well to engage her thinking not as settled wisdom but as challenge, provocation, and resource for ongoing work.

Jade Vermeersch (Belgium), 34 | Science Communication Specialist

You documented how married women couldn’t control their own patents in the 1880s, yet modern patent law – at least in theory – treats all applicants equally regardless of gender. And yet women still file fewer patents, receive less venture capital for innovations, and see their contributions attributed to male colleagues. In your research on women inventors, did you identify any barriers that were purely legal versus those that were cultural or educational? Because I’m wondering whether fixing the law – which we largely did – was ever sufficient to change outcomes, or whether the cultural architecture you described runs too deep? Put differently: if Catherine Greene had lived in 2026 with full legal rights to her cotton gin patent, would the recognition problem have solved itself?

Miss Vermeersch, you have identified the very heart of the matter with admirable clarity. Your question forces me to disentangle what I perhaps did not distinguish sharply enough in my own writing: the difference between legal impediment and cultural devaluation, and whether remedying the former can ever fully address the latter.

Let me be direct: the legal barriers I documented were necessary conditions for women’s exclusion from recognition as inventors, but they were never sufficient explanations for that exclusion. Even where law permitted women to hold patents – and there were some jurisdictions, particularly toward the latter part of my life, where unmarried women or widows possessed such rights – the cultural architecture you describe still operated with full force.

I documented cases of women who patented inventions under their own names and yet found that when those inventions were discussed in the technical press, in commercial catalogues, or in histories of innovation, the credit migrated to male associates. The legal right to attribution existed on paper; the cultural practice of attribution followed different channels entirely. This is what I meant when I wrote about society’s disapproval of women who invent. It is not merely that we were legally prevented – though we were – but that we were culturally discouraged, intellectually isolated, and strategically erased even when we succeeded.

Now, you ask whether the barriers were purely legal versus cultural or educational. I must tell you: they were never separable in practice, though they are analytically distinct. Consider the operation of the patent system as I observed it. A woman seeking a patent required technical knowledge – knowledge she was prevented from acquiring through formal education. She required access to workshops and tools – access that was deemed improper for respectable women. She required capital to develop prototypes and file applications – capital she could not control if married, and struggled to accumulate if unmarried. She required social networks within technical and commercial communities – networks from which she was excluded by convention and sometimes by explicit rule.

So even when the law permitted her to file a patent, every preceding step in the process presented obstacles that were cultural and educational rather than strictly legal. The law was the final barrier, but hardly the only one. And here is what your question illuminates: removing the final barrier does not dismantle the preceding ones. It merely makes the exclusion less visible, more deniable, easier to attribute to women’s own choices or capacities rather than to institutional design.

You mention that women in your era file fewer patents, receive less venture capital – I confess I do not know what venture capital is, but I infer it means financial backing for commercial development – and see their contributions attributed to male colleagues. This does not surprise me in the slightest. What you are describing is the persistence of cultural devaluation in the absence of formal legal exclusion. The mechanisms have become subtler, but the outcome remains structurally similar.

Now, to your specific question about Catherine Greene and the cotton gin. If she had lived in 2026 with full legal rights to patent her invention, would the recognition problem have solved itself? I must answer: almost certainly not, though the nature of the problem would have shifted.

Suppose Greene possessed the legal right to file the patent under her own name, to control its commercialisation, to defend it against infringement. She would still face the question of credibility. When Eli Whitney presented the device to planters and merchants, they would ask: who invented this? If Whitney said “Mrs. Greene,” would they believe him? Would they take the invention as seriously? Would they invest in its production with the same confidence?

I documented numerous cases where women’s inventions were dismissed as trivial, decorative, or derivative even when properly attributed. The cultural assumption was that women’s mechanical capacity was limited to refinements of existing devices or to innovations in domestic economy. An invention with significant commercial and agricultural implications, emerging from a woman’s workshop, would be met with scepticism. Not because the device did not function – function is objective and can be demonstrated – but because the narrative of female invention did not accommodate such significance.

Greene would have faced a choice familiar to many women inventors: present the device under her own name and accept commercial limitations and scepticism, or permit a male associate to present it and secure broader adoption at the cost of personal credit. Many women chose the latter, and I do not fault them for it. They made rational calculations under constrained circumstances.

But here is where your question becomes most penetrating. You ask whether fixing the law was ever sufficient. And I must tell you plainly: no. The law was necessary but insufficient. Legal reform creates possibility but does not guarantee practice. It removes formal barriers but leaves informal ones intact. It permits women to enter systems but does not transform those systems to accommodate women’s full participation.

This is why I insisted – and why I became so unpopular for insisting – that women’s liberation required more than securing specific rights within existing systems. It required challenging the cultural, religious, and educational foundations that produced female subordination in the first place. The suffragists who believed that securing the vote would automatically remedy all other inequalities were engaged in wishful thinking. Rights are tools, not solutions. They permit action but do not compel recognition.

What your era faces, Miss Vermeersch, is the harder question: how to dismantle cultural devaluation when the legal architecture no longer provides an obvious target for reform. You cannot simply demand that the law grant women patent rights – you already possess them. You cannot demand access to technical education – you already have it, at least formally. What remains is the subtle, pervasive, difficult-to-challenge practice of attribution, credibility, and recognition.

This is the work I attempted in my writing on women inventors: to make visible the mechanisms by which women’s intellectual contributions are devalued and erased despite their formal equality. I documented patterns. I named specific women. I articulated the structural sources of erasure. But I had no simple remedy to offer, because the problem is not one of legal reform but of cultural transformation. That transformation requires relentless documentation, public challenge to misattribution, institutional accountability, and – perhaps most importantly – women’s insistence on credit for their own work, even when doing so invites ridicule or professional cost.

I will say one final thing: the fact that modern patent law treats all applicants equally “in theory” but produces unequal outcomes in practice is precisely the situation I attempted to describe in 1870. The appearance of neutrality conceals the operation of bias. This is more insidious than explicit exclusion, because it permits those who benefit from the current arrangement to deny that any problem exists. They can point to the law and say: see, women are permitted. If they do not succeed, that must reflect their own choices or capacities. This is how cultural architecture runs too deep, as you so aptly phrase it. It operates beneath the surface of formal equality, producing outcomes that appear to confirm natural differences but in fact reflect institutional structures that remain largely unexamined and unchallenged.

Your generation faces the harder work: transforming culture rather than merely reforming law. I do not envy you the task, but I believe you are better equipped for it than my generation was. You have language for these phenomena – gender bias in attribution, structural inequality, cultural devaluation. We were inventing that language as we went. Use it well. Document meticulously. Insist on credit. Make the invisible mechanisms visible. That is the work that remains.

Mattias Fredriksson (Sweden), 41 | Institutional Historian

During your lifetime, you witnessed the conservative faction of the suffrage movement actively distance themselves from your work – the 1913 repudiation of Woman, Church and State was deliberate institutional choice. Were there moments when you considered that the conservative suffragists might have been strategically correct, even if ideologically wrong? Not that you should have compromised, but that perhaps narrowing the movement’s scope was the only path to achieving the vote by 1920? And if so, what do you make of the fact that once women had the vote, the broader liberation agenda you envisioned still hadn’t materialised? Did winning the narrow victory actually make broader transformation harder because people believed the ‘women’s problem’ was solved?

Mr. Fredriksson, you have asked the question I have spent the last years of my life attempting to avoid. And I will answer you with the honesty you deserve, though the answer is not one that flatters my own judgment.

Yes. There were moments – many moments – when I wondered if the conservative suffragists were strategically correct, even if ideologically wrong. I would be dishonest if I claimed otherwise.

Let me explain the nature of my uncertainty. In 1869, when we founded the National Woman Suffrage Association, the path to victory was unclear. We had no certainty that we would ever achieve the vote. We did not know whether we were twenty years away, fifty years away, or pursuing an impossible goal. Under such circumstances, the question of strategy becomes genuinely difficult. Do you pursue the broadest possible agenda – addressing every dimension of women’s oppression – knowing that this breadth may alienate potential supporters and doom the entire enterprise? Or do you narrow your focus to a single, specific, achievable goal – the ballot – accepting that this means abandoning or postponing other necessary reforms?

The conservative suffragists who pushed the 1890 merger were not acting from mere cowardice or intellectual limitation. Many of them were intelligent, principled women who had genuinely convinced themselves that securing the vote was the prerequisite for all other reforms. Their logic was this: once women possessed political power, all other inequalities would follow naturally. The vote would create leverage for every other demand.

And I will acknowledge: there is a coherence to this logic. There is a plausibility to it. I cannot say with absolute certainty that they were wrong, because I do not possess the ability to observe the historical path we did not take.

What I can say is this: the evidence available to me suggested that their logic was faulty. I had watched reform movements narrowed and captured before. I had observed how specific, limited victories often become endpoints rather than entry points for broader change. I had studied the history of reform and seen how movements lose their radical edge once they achieve their initial goals. The tendency of successful movements is to consolidate around their victory and resist further transformation, not to use that victory as a springboard for deeper change.

But I will be candid with you: I was not certain. My opposition to the merger was principled, but it was not based on guaranteed knowledge of historical outcomes. I was making a judgment about probable trajectories, not asserting certain truth.

Now, to your second question – whether winning the narrow victory made broader transformation harder – I must give you a more complicated answer, because the evidence on this point has accumulated over the decades since my death, and I can now see patterns I could not have foreseen.

It appears that you are correct. The achievement of women’s suffrage in 1920 was accompanied by what I can only describe as a narrowing and domestication of feminist aspirations. Women obtained the vote – and then, remarkably quickly, the political energy that had animated the suffrage movement dissipated. The organisations that had pushed for decades suddenly seemed to lose urgency and focus.

Why did this occur? I have several hypotheses, though I acknowledge these are interpretations rather than documented fact.

First, the very success of the suffrage campaign created what I might call a “sufficiency illusion.” Mainstream society embraced the narrative that women’s exclusion from politics had been the root problem, and that securing the vote had remedied this exclusion. Women now had political power, the argument went. What more could they possibly need? This narrative was false – the vote did not automatically translate into substantive political power – but it was remarkably effective in dampening further demands for change.

Second, the organisations that led the suffrage campaign became invested in the respectability that had enabled their success. The conservative faction had successfully positioned the movement as reasonable, moderate, compatible with Christian morality and existing social order. Once the vote was achieved, these organisations had no incentive to abandon the posture of respectability and challenge deeper structures of inequality. To do so would have alienated the very constituencies whose support had been necessary for victory.

Third, and most troubling, I suspect that the suffrage itself became, in practice, far less transformative than its theory suggested. Women received the ballot, but the political system into which they entered was already structured around interests that did not necessarily align with women’s liberation. Women’s votes could be captured by existing parties and interests. Women could be absorbed into the political system without transforming that system’s fundamental character. In other words, women were permitted entry to a game whose rules had been established without their participation and were not designed to serve their interests.

I think often of Susan B. Anthony in these reflections. Susan was absolutely convinced that securing the vote was the key that would unlock all doors. I disagreed with her, but I understood the source of her conviction. She had devoted her entire adult life to this single goal. It had become, for her, the symbol and substance of women’s liberation. When the vote was finally achieved – after her death, though she lived to see it come within reach – it validated her entire life’s work. The narrative that the vote was the essential reform became institutionalised because so many people had sacrificed so much to achieve it.

But this narrative prevented the deeper questions from being asked. It prevented the examination of whether the political system itself – with its competition for wealth and power, its indifference to reproduction and care work, its alliance with economic interests hostile to women’s autonomy – could ever truly serve women’s liberation, even with women’s formal participation.

This is what I feared would happen, Mr. Fredriksson. And it appears my fears were justified.

Now, does this mean my opposition to the 1890 merger was correct? Or does it mean that the conservative suffragists’ strategy, though it did not produce the transformative results they promised, was the only viable path to even the limited victory of suffrage itself?

I find myself unable to answer this with certainty. It is possible – perhaps even likely – that a broader feminist agenda, pursued uncompromisingly, would never have achieved the votes necessary to amend the Constitution. It is possible that the narrowing of focus was the price of victory, and that without this narrowing, women would still be without the ballot in your era. I cannot prove otherwise.

But I will say this: I observe that even the limited victory of suffrage has begun to erode or become taken for granted. The organisations that fought for it have dissipated or become absorbed into mainstream politics. The sense of women as a constituency with distinct interests and demands has weakened. There is no institutional force carrying forward the radical demands for women’s liberation that existed before the suffrage movement contracted itself.

What if the Woman’s National Liberal Union, or some organisation like it, had remained vital and visible? What if there had been a competing centre of feminist energy that refused to accept the suffrage as endpoint? What if the conversation about women’s liberation had continued, after 1920, to address the full range of issues – reproductive autonomy, economic independence, religious authority, indigenous sovereignty – that I had insisted were inseparable from the question of political rights?

I do not know if such an organisation could have achieved more fundamental transformation. But I suspect it might have prevented the narrowing that occurred, might have kept alive the question of what women’s political power should actually be used for, might have resisted the absorption of feminist energy into mainstream political parties pursuing their own interests.

This is the question that haunts me, Mr. Fredriksson. Not whether I was right to oppose the merger – on principle, I remain convinced I was. But whether my opposition had any strategic effect whatsoever, or whether the conservative victory was inevitable regardless of what I did. Whether my principled stance against pragmatism was anything more than an individual conscience refusing complicity, without actually changing the arc of history.

I suspect the honest answer is this: the conservative suffragists were probably right that their narrow strategy was necessary to achieve the specific goal of suffrage. But in achieving that goal, they sacrificed the possibility of deeper transformation. They won a battle and, in doing so, potentially lost the war. Whether a different strategy could have achieved both the vote and broader liberation – I do not know. The historical path we did not take remains forever inaccessible to analysis.

What I can say is that the outcome validates my original scepticism about the sufficiency of narrow victory. Women obtained the ballot and discovered that the ballot, alone, did not liberate them. The institutions that governed their lives – religious, legal, economic, familial – remained largely unchanged. The vote was a necessary condition for further reform, but it proved far less sufficient than even moderate reformers had anticipated.

This suggests to me that your own era faces a similar choice to the one we faced. You have, I gather, achieved greater formal equality than we could have imagined – in education, in employment, in legal standing. And yet you tell me that women still face profound inequalities in recognition, in authority, in bodily autonomy. The question you must ask is whether these inequalities are merely remnants of past exclusion that will gradually disappear as equality becomes more entrenched, or whether they reflect deeper structural features of your society that equality alone cannot address.

My fear – and I think the evidence supports this fear – is that formal equality can coexist with substantive inequality indefinitely, if the institutions that produce that substantive inequality are never directly confronted and transformed. The conservative suffragists believed that political power would automatically challenge all other institutions. I believed that institutional structures could absorb even significant formal changes without experiencing fundamental transformation.

The evidence, I regret to say, appears to support my more pessimistic assessment. But I wish I had been proven wrong.

Brynja Stefánsdóttir (Iceland), 38 | Anthropologist specialising in Indigenous Knowledge Systems

Your initiation into the Iroquois Wolf Clan and admission to the Council of Matrons was extraordinary – you weren’t merely studying their matrilineal system, you were being recognised as someone who understood it. In spending time among the Iroquois and then writing about their society for American audiences, did you ever worry about how your interpretations might be weaponised or misunderstood? About how later scholars or activists might use your framework of Iroquois ‘matriarchy’ in ways that romanticise or appropriate Indigenous knowledge rather than genuinely learning from it? You acknowledged earlier that you may have overstated some aspects of female authority. But more fundamentally, as a settler engaging with Indigenous society during a period of active colonisation, how did you address the ethics of that work?

Miss Stefánsdóttir, you have asked me a question that I am not certain I can answer adequately, because the terms in which you frame it – the ethics of cross-cultural research, the danger of weaponisation and appropriation – reflect a consciousness about these matters that my generation did not possess, or possessed only dimly.

Let me begin with what I did worry about, and then speak to what I perhaps should have worried about but did not.

What I worried about was accuracy. I worried that my interpretations of Iroquois society might be incorrect, that I might misunderstand what I observed, that my own assumptions and desires might colour what I reported. I spent considerable time among the Iroquois precisely to avoid the errors of armchair scholarship – of men like Lewis Henry Morgan, whose work I studied, who theorised about indigenous societies from a distance or through brief, mediated encounters. I believed that extended, direct observation would give me access to truth that theoretical speculation could not provide.

But you are asking me something more troubling: whether I worried that my interpretations, even if accurate, might be used in ways that harmed the Iroquois or misrepresented them. And I must confess to you that this question did not occupy my thinking as it perhaps should have.

I wrote for an American audience – primarily white, educated, reform-minded Americans who knew almost nothing of Iroquois society beyond hostile stereotypes and government propaganda justifying dispossession. My purpose was dual: to demonstrate that female authority was not a theoretical impossibility, and to challenge the narrative that indigenous peoples were uniformly savage and uncivilised. I wanted my readers to understand that the Iroquois had developed political and social structures of genuine sophistication, structures that in some respects surpassed those of Christian civilisation in their recognition of women’s authority and autonomy.

Did I worry that this might romanticise or simplify? To some degree, yes. I was aware that any account I gave would necessarily be partial and simplified. The full complexity of Iroquois society – the internal debates, the variations between different nations of the Confederacy, the ways in which practice deviated from ideal – could not be fully captured in the essays and chapters I wrote for American audiences unfamiliar with any of it.

But here is what I did not adequately consider: the political context in which I was writing. The Iroquois were not simply an alternative society I could study and learn from. They were a nation under active assault by the United States government. Their treaty rights were being violated. Their lands were being taken. Their children were being forcibly removed to boarding schools designed to destroy their culture and language. The federal government was attempting to impose individual property ownership and American citizenship upon them, explicitly for the purpose of eliminating their status as sovereign nations.

I wrote against these policies. I argued vehemently that the federal government’s treatment of indigenous peoples was unjust, that treaties must be honoured, that enforced citizenship was a violation of sovereignty. I believed I was acting in solidarity with the Iroquois cause.

But you force me to ask: was my use of Iroquois society as an example in my arguments for women’s rights actually serving Iroquois interests? Or was it, however well-intentioned, a form of extraction – taking knowledge from their society to advance my own political purposes?

I do not have a comfortable answer to this. I can tell you what I believed at the time: that making visible the sophistication and justice of Iroquois political structures would serve both feminist purposes and indigenous interests. If Americans could see that female authority functioned successfully among the Iroquois, they might question whether women’s political exclusion in their own society was necessary or natural. And if they came to respect Iroquois political structures, they might be less willing to support policies aimed at destroying those structures.

But I see now that this logic was self-serving. It treated the Iroquois as evidence for claims I was making, rather than as autonomous actors with their own purposes and interests that might not align with mine. It asked: what can the Iroquois teach us about women’s rights? It did not adequately ask: what do the Iroquois themselves need, and how can I support those needs without subordinating them to my own agenda?

You mention the danger that my framework of Iroquois “matriarchy” might be used to romanticise or appropriate indigenous knowledge. I see this danger clearly now, though I confess I did not see it as sharply when I was writing. The risk is that my account becomes a kind of myth – noble savages with perfect gender equality – that bears little relation to the complex reality of Iroquois society. This mythologised version can then be deployed by later activists and scholars in ways that serve their purposes while actually obscuring or harming real Iroquois people.

And you are correct that I overstated certain aspects. I was so eager to demonstrate that female authority was possible that I may have described Iroquois women’s power as more absolute and less contested than it actually was. I emphasised the structural features – descent through the female line, female control of property, the Council of Matrons’ authority – without adequately examining the ways in which male authority also operated, or the ways in which women’s theoretical power might be practically constrained.

The more fundamental ethical problem you raise is this: as a settler engaging with indigenous society during active colonisation, what right did I have to this knowledge at all? And how could I use it responsibly given the vast power imbalance between my society and theirs?

This is where I must be most honest with you: I do not think I resolved this tension adequately. I believed that my personal relationships with Iroquois women who welcomed me, who initiated me into the Wolf Clan, who shared their knowledge with me – I believed these relationships gave me permission and even responsibility to share what I learned. The name Karonienhawi was given to me by the Council of Matrons. I understood this as recognition that I had earned some degree of trust and authority to speak about what I observed.

But – and here is where your question becomes most penetrating – individual relationships and permissions do not necessarily resolve questions of collective impact. Even if specific Iroquois women welcomed my presence and my writing, this does not mean that the broader effect of my work was beneficial to the Iroquois as a people. It does not mean that I adequately considered how my interpretations might be used by others in ways I did not intend or control.

Let me give you a specific example of my failure to think through these implications. I argued that the Iroquois represented an ancient matriarchy that had survived into the modern era. This was an interpretation influenced by my reading of certain ancient historians and my own desire to find historical precedent for female authority. But this framing – presenting the Iroquois as a survival of an ancient past rather than as a contemporary political society with its own ongoing development – may have contributed to the American tendency to see indigenous peoples as remnants of history rather than as living, changing nations with rights and interests in the present.

I did not intend this effect. I thought I was honouring Iroquois society by connecting it to ancient civilisations I admired. But the unintended consequence may have been to reinforce the very temporal logic that justified dispossession: the idea that indigenous peoples belonged to the past and would inevitably give way to modern American civilisation.

Miss Stefánsdóttir, I am struggling to answer your question adequately because I am being forced to recognise failures I did not acknowledge during my lifetime. I believed I was acting ethically because I was opposing government policies, because I was received with honour by the Iroquois, because I was attempting to represent their society accurately. But I did not adequately consider the structural position from which I was writing – as a member of the settler society that was actively dispossessing and attempting to eliminate the Iroquois as a distinct people.

The fact that I opposed specific policies did not change this fundamental relationship. I was still writing primarily for a white American audience, still using Iroquois knowledge to advance arguments designed for that audience, still benefiting personally and politically from access to knowledge that was not originally mine.

What should I have done differently? I am not certain. Should I have refrained from writing about the Iroquois entirely? But this seems like abandonment – a refusal to use whatever platform I possessed to challenge the narratives that justified their mistreatment. Should I have written differently, foregrounding Iroquois voices rather than my own interpretations? Perhaps, though the conventions of scholarship and political argument in my era did not readily accommodate such an approach. Should I have subjected my work to review by Iroquois authorities before publication? This seems obvious now, though I confess it did not occur to me then.

I think the most honest answer I can give you is this: I was inadequately conscious of the ethical complexities you describe. I thought carefully about accuracy and respect in my observations. I did not think carefully enough about the politics of representation, about who benefits from the circulation of particular narratives, about how my work might be weaponised or misused by others.

And I must acknowledge something more troubling still: I am not certain I would have changed my approach even if these concerns had been raised to me during my lifetime. I was so convinced of the importance of my feminist arguments, so certain that demonstrating the historical possibility of female authority was essential to challenging women’s oppression, that I might have accepted risks to the Iroquois as the necessary cost of advancing women’s liberation more broadly.

This calculus – prioritising my political agenda over the potential harms to the community I was writing about – is precisely the kind of extraction and appropriation you are warning against. I recognise it now. I am not certain I recognised it sufficiently then.

What guidance can I offer to scholars in your era who face similar questions? Only this: do not assume that good intentions, personal relationships, or opposition to specific harmful policies are sufficient to resolve the ethical problems of cross-cultural research. The structural relationships of power matter more than individual intentions. The long-term effects of how knowledge circulates matter more than the immediate purposes for which you deploy it.

And perhaps most importantly: be willing to subordinate your own agenda when necessary. If advancing your political arguments requires using another community’s knowledge in ways that might harm them or distort their representation, you must be willing to refrain. The fact that their knowledge would advance your cause does not give you the right to it. This is a discipline I did not adequately practice, and I cannot claim that history has vindicated my choices.

I am grateful to have been welcomed by the Iroquois, to have received the name Karonienhawi, to have been admitted to the Council of Matrons. These remain among the greatest honours of my life. But honour does not equal ethical clarity. I was honoured, and I may still have acted in ways that prioritised my interests over theirs. You ask how I navigated the ethics of that work, and the truthful answer is: not as carefully as I should have.

Armands Pētersons (Latvia), 52 | Comparative Social Movements Scholar

You split from the mainstream suffrage movement in 1890 to preserve radical principles, and you accepted marginalisation as the cost. But what if – hypothetically – the Woman’s National Liberal Union had remained organisationally viable after your death? What if it had grown rather than faded? Would a surviving radical feminist organisation have provided a counterbalance to NAWSA’s conservatism in the early twentieth century, potentially preventing some of the co-optation you feared? Or were the material conditions of your time such that the conservative victory was inevitable regardless? In other words, was your split a principled but ultimately ineffectual gesture, or could it theoretically have altered the trajectory of American feminism if external circumstances had been different?

Mr. Pētersons, you have asked the question that every person who makes an unpopular choice in service of principle must eventually confront: was my choice meaningful, or was I simply gesturing toward principle while history moved along its predetermined path regardless?

This is a question I cannot answer with certainty, and I suspect that is precisely why it is worth asking.

Let me begin by acknowledging what we cannot know. We cannot observe the historical trajectory we did not take. We cannot run history as an experiment with different variables to see what would have resulted from different organisational choices. The Woman’s National Liberal Union existed as a smaller, more marginal organisation than the National American Woman Suffrage Association. It did not grow substantially. It did not achieve the political influence that the conservative suffrage movement achieved. By any conventional measure of success, my choice to split and maintain radical principles resulted in diminished power and influence.

But here is where I must distinguish between immediate effects and long-term effects, between visible effects and structural effects.