You are driving home on a Tuesday. The day has been fine – not great, not terrible, just a standard Tuesday. Then, a song comes on the radio. It might be Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide,” or it might be a seemingly disposable pop ballad you haven’t heard since 2011. Suddenly, without permission or warning, your throat tightens. The road blurs. You are weeping at a red light, feeling a profound sense of loss for something you can’t quite name.

This experience is universal, but it feels intensely private. It also feels irrational. Why does organised sound – literally just vibrations in the air – trigger a biological survival response (tears, chills, elevated heart rate) in the absence of actual danger?

The answer is that you are not crying for “no good reason.” You are crying because music is a sophisticated technology that hacks your brain’s prediction systems, hijacks your memory, and simulates the structural forms of human suffering.

The Physics of Heartbreak (Music Theory)

If you strip away the lyrics, the “sadness” of a song is often a mathematical equation. Composers have spent centuries refining specific acoustic devices that bypass your intellect and hit your nervous system directly.

The Musical Sigh: The Appoggiatura

The most potent weapon in a tear-jerker’s arsenal is the appoggiatura (from the Italian appoggiare, “to lean”).

An appoggiatura is a note that clashes with the harmony underneath it. It creates a temporary dissonance – a moment of musical pain or tension – that demands a resolution. When the note finally resolves to the harmonious chord, the listener feels a physical release of tension.

A classic example is the chorus of Adele’s “Someone Like You.” When her voice breaks upward on the word “you,” she is often hitting an appoggiatura. The note leans painfully against the harmony before settling. Acoustically, this mimics the sound of a human voice cracking or sighing. Your brain hears this “sigh” and fires mirror neurons that simulate the feeling of crying, even if you aren’t sad.[1][2]

The Sound of Giving Up: The Lament Bass

Another structural trick is the “Lament Bass” or descending tetrachord. This is a bassline that steps down four distinct notes (e.g., A-G-F-E).

This pattern has signified grief in Western music since the 17th century. It mimics the physical sensation of sinking, falling, or exhaling a final breath. When we hear a melody that droops and a bassline that sinks, our bodies unconsciously interpret it as a loss of energy – the acoustic equivalent of giving up.[3][4]

| Musical Device | Acoustic Characteristic | Biological Simulation |

| Appoggiatura | Dissonance resolving to consonance | A voice cracking, sighing, or releasing tension |

| Lament Bass | Descending scale steps | Sinking, falling, loss of vitality |

| Minor Thirds | Lowered pitch interval | The prosody (tone) of a sad speech or weeping |

The Brain’s Prediction Machine (Neuroscience)

While music theory explains the sounds, neuroscience explains why they hurt. The leading theory comes from musicologist Leonard Meyer and later David Huron: emotion in music arises from thwarted expectations.[5][6]

Your brain is a prediction machine. When you listen to a song, you are constantly betting on what note comes next. If the song does exactly what you expect, it is boring (think: “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star”). If it is too chaotic, it is noise.

The “wrecking” songs live in the sweet spot. They tease you. They delay the resolution you crave, creating a micro-dose of anxiety. When the resolution finally hits (the “drop” or the final chord), your brain floods with dopamine – the same chemical released during eating or sex.

The ITPRA Model

David Huron’s ITPRA model breaks this down into five stages of reaction:[7][8]

- Imagination: You unconsciously imagine the next note.

- Tension: Your body prepares for the outcome (arousal increases).

- Prediction: The note hits (or doesn’t).

- Reaction: A fast, unconscious reflex (e.g., a gasp).

- Appraisal: You consciously realise, “Ah, that was beautiful.”

The “chills” or “frisson” you feel – that shiver down your spine – is actually a “skin orgasm.” It is a vestigial piloerection response (hair standing on end). In the wild, this happens when we are cold or threatened. In music, it happens when the violation of our expectations is so surprising and touching that our primitive brain signals a moment of intense vulnerability.[9]

The Ghost in the Machine (Memory)

Sometimes the music isn’t hacking your biology; it’s hacking your timeline. The reason a specific song wrecks you is often due to the Reminiscence Bump.

Research shows that the music we listen to between the ages of roughly 12 and 22 sticks to us harder than music from any other period. This is the era when your neural pathways are solidifying, and your identity is forming.[10][11]

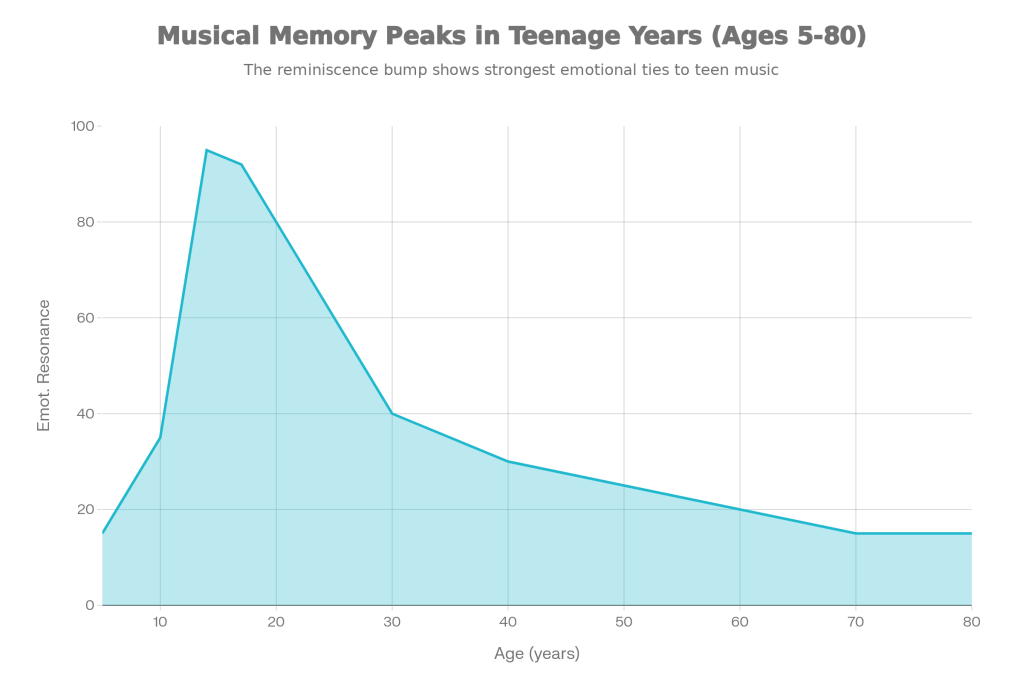

As the chart above illustrates, our emotional resonance with music peaks dramatically during adolescence. The songs from this “bump” period are not just files in your brain; they are entangled with your self-concept.

When you hear a song from this era, you are experiencing a Music-Evoked Autobiographical Memory (MEAM). Unlike visual memories, which you often have to “search” for, musical memory is involuntary. It bypasses the brain’s executive control and hits the limbic system (the emotion centre) directly.[12][13]

You aren’t just remembering 2008; you are simulating the neural state you were in during 2008. If that version of you was heartbroken, hopeful, or naive, the song forces you to inhabit that skin again. You cry because you are briefly possessed by a ghost: yourself.

The Philosophy of “Enjoyable Sadness”

Finally, we must ask: If this wrecks us, why do we like it? Why do we build playlists specifically to make us cry?

The Paradox of Tragedy

Philosopher David Hume called this the “Paradox of Tragedy.” Logic suggests we should avoid pain, yet we pay money to see tragic operas and listen to breakup albums. Hume argued that we don’t enjoy the pain; we enjoy the eloquence of the pain. The beauty of the artistic form converts the raw, ugly emotion into something pleasurable.[14]

Forms of Feeling

Susanne Langer, a philosopher of mind, offered perhaps the most profound explanation. She argued that language is good at describing facts, but terrible at describing feelings. You can say “I am sad,” but that doesn’t capture the sinking, heavy, dark texture of grief.

Langer argued that music is the form of feeling. A song doesn’t just describe sadness; it traces the shape of sadness – its rise, its fall, its tension, and its release. When we listen to a song that wrecks us, we feel a deep sense of recognition. We cry because, for three minutes, something in the external world understands our internal world perfectly.[15][16]

Conclusion: The Mercy of Being Wrecked

The “no good reason” is actually a dozen reasons working in concert. You are crying because the acoustics are mimicking a human sigh; because your dopamine receptors are recovering from a delayed prediction; because you are mourning the teenager you used to be; and because the music has given a voice to a feeling you couldn’t name yourself.

In a world that often demands we be numb to function, the song that breaks you is a vital reminder. It proves that despite the callouses of adulthood, the machinery of your heart is still working.

References

[1] Why Adele’s “Someone Like You” and its appoggiaturas …

[2] Anatomy of a Tear Jerker: Why does Adele make everyone …

[3] Shea | Descending Bass Schemata and Negative Emotion …

[4] Descending Tetrachords: Muse and Handel are both sad

[5] 24 What Comes Next? Musical Expectancy – Oxford Academic

[6] Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation

[7] Psychological Anticipation – TheisticScience.com

[8] The Role and Definition of Expectation in Acousmatic …

[9] Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with …

[10] Reminiscence bump invariance with respect to genre, age … – NIH

[11] Why Teenage Songs Define Us: The Science of Musical …

[12] Music-evoked autobiographical memory

[13] Exploring the nature of music-evoked autobiographical …

[14] Hume on the Paradox of Tragic Pleasure

[15] Pioneering Philosopher Susanne Langer on What Gives …

[16] Music is ‘significant form,’ and its significance is that…

[17] Susanne K. Langer

[18] ITPRA theory – A theory on brain processing | The Biased Mind

[19] Revisiting the musical reminiscence bump

[20] Philosophy in a New Key Quotes by Susanne K. Langer

[21] Frontiers | Revisiting the musical reminiscence bump: insights from neurocognitive and social brain development in adolescence

[22] Review article

[23] A Cross-Sectional Study of Reminiscence Bumps for Music-Related Memories in Adulthood – Kelly Jakubowski, Tuomas Eerola, Barbara Tillmann, Fabien Perrin, Lizette Heine, 2020

[24] Susanne K. Langer’s Philosophy on Music and …

[25] Team Development Stages – Tuckman Model Explained

[26] Effect of popular songs from the reminiscence bump as …

[27] The assignment of meanings [in music] is a shif…

[28] Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation

[29] Global study shows why the songs from our teens leave a lasting mark on us

[30] Revisiting Susanne Langer’s Philosophy in a New Key – …

Bob Lynn | © 2026 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved. | Prompt by Eric Foltin

Leave a comment