What is something others do that sparks your admiration?

Wednesday, 10th December 1913

You will forgive me, I hope, if I speak plainly. I have been twenty-three years in this office – longer than some of you have drawn breath – and I have learnt that there are two sorts of men in this world: those who understand that order is the very sinew of civilisation, and those who persist in believing that muddle is somehow the natural state of affairs. The latter sort I have been obliged to supervise for most of my working life.

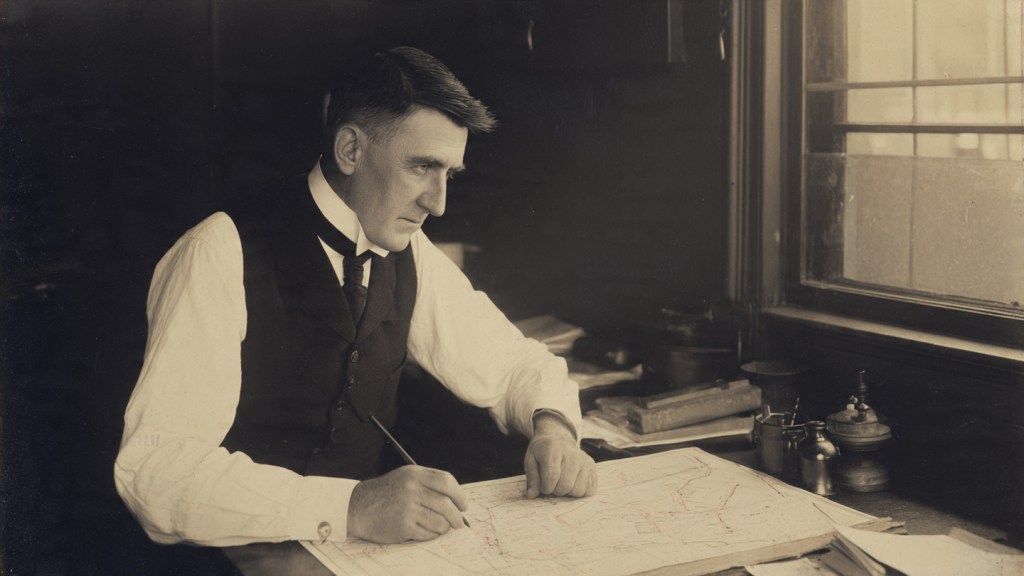

I am chief clerk at Hawdon & Sons, shipping agents, down by the Albert Dock. My desk commands a view of the warehouse floor, and upon that desk sits the great chart of the Eastern routes – India, Ceylon, the Straits – marked in red ink according to the sailing schedules, and in black where cargo is logged and expected. It is my chart. I drew it myself, for the one supplied by Head Office was riddled with errors and omissions that would have shamed a schoolboy. Every line is ruled true; every port marked to scale. When I look at it I see what this firm ought to be: precise, methodical, predictable as the tides.

And yet chaos encroaches daily. Bills of lading arrive in the wrong order. Manifests are mislaid. Young Barker in the counting-house contrives to spell “Calcutta” three different ways in the same ledger. I correct him, naturally, and he grins – grins! – and promises to do better, though we both know he shan’t. It is not malice, I grant you; it is simply that he lacks the temperament for rigour. Most men do. They are content with “near enough” and “roughly speaking,” as though approximation were a virtue.

I do not say this to exalt myself. If anything, I am aware – acutely aware – that my own nature borders on the tyrannical. I have been told so. My wife remarks, with what I believe is intended as affection, that I would rearrange the stars if I could reach them. Perhaps I would. There is a satisfaction in seeing things set to rights that I cannot adequately explain, and an almost physical discomfort when they are not. I have re-filed the entire shipping correspondence these past five years because I could not bear the previous clerk’s method, which appeared to rest upon no method whatsoever. Call it a weakness if you will; I have no other name for it.

But here is the curious thing. You ask me – or at least, you might ask me, were we conversing face to face – what is it that others do that stirs my admiration? I shall tell you. It is precisely that quality I lack and cannot seem to acquire: the capacity to set a thing aside when it is not quite perfect, and to carry on regardless. Old Howlett, the foreman, does it daily. He knows full well that the crates in Bay Seven are stacked crookedly; that the inventory is three weeks out of date; that half the dockers cannot read the labels I so painstakingly write. And yet he shrugs – he actually shrugs – and says, “Well, Mr. Crowle, it’ll do. It’ll see us through.” And the maddening thing is, it does. The ships sail. The cargo arrives. Trade continues, in spite of imperfection.

I confess I do not know how he manages it. I watch him sometimes from my window, striding across the cobbles with that easy, rolling gait of his, giving orders left and right, and the men obey him without question. They like him, which is a thing they do not say of me. When I give an order, it is obeyed because I am their superior; when Howlett gives one, it is obeyed because they trust him to know what must be done and what may be left to chance. There is a kind of genius in that, I think, though I am not constituted to imitate it.

You will have gathered by now that I am not a man much given to leisure or frivolity. My evenings are spent reviewing the day’s work; my Sundays, in checking over the charts for the week to come. It is not that I am a slave to duty – or rather, perhaps I am, but I am also a slave to the conviction that if I relax my grip for even a moment, the whole edifice will come tumbling down. Chaos waits at every threshold. One mis-entered figure, one unsigned manifest, one cargo sent to the wrong hold, and the consequences ripple outward like a stone thrown into still water. I have seen it happen. I have spent days – weeks – untangling the results of another man’s carelessness, and I am determined it shall not happen on my watch.

And yet I grow weary. There, I have said it. I grow weary of the endless vigilance, the constant corrections, the knowledge that if I were to vanish tomorrow, the office would descend into chaos within a fortnight. It is both my pride and my burden. I look at Howlett and his ilk, and I wonder what it must be like to shrug and say, “It’ll do.” I wonder, and I know I shall never learn the trick of it.

So here we are, you and I. You have listened – if you are still listening – to the ramblings of a man who cannot abide a crooked line or a misplaced decimal, and who has made a career of correcting other men’s errors. I do not expect your sympathy. I scarcely expect your understanding. But if you have ever felt the weight of holding everything in place, of being the lone bulwark against disorder, then perhaps you will comprehend a little of what I am telling you. Order is a fragile thing. It must be defended daily, hourly, against the tide of human carelessness. And I – God help me – I am its defender, whether I will or no.

Now, if you will excuse me, there is a discrepancy in this morning’s receipts that wants attending to.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to Tony Cancel reply