This interview is a dramatised reconstruction: Kathleen Antonelli died in 2006, and the dialogue is imaginatively composed rather than a real transcript. It is grounded in historical sources about her life, work, and recorded remarks, but the voice and scene-setting remain interpretive and cannot replace primary materials.

Kathleen Antonelli (1921-2006), born Kathleen McNulty in County Donegal, Ireland, was a pioneering mathematician and one of the six original programmers of ENIAC, the world’s first general-purpose electronic digital computer. Despite being classified as a “computer” and instructed to pose as a hostess during the machine’s public unveiling, she fundamentally shaped the architecture of modern software by inventing the subroutine and mastering direct machine logic. Her legacy, long obscured by gendered erasure and institutional secrecy, now stands as the bedrock of the digital age, bridging the gap between human calculation and stored-program computing.

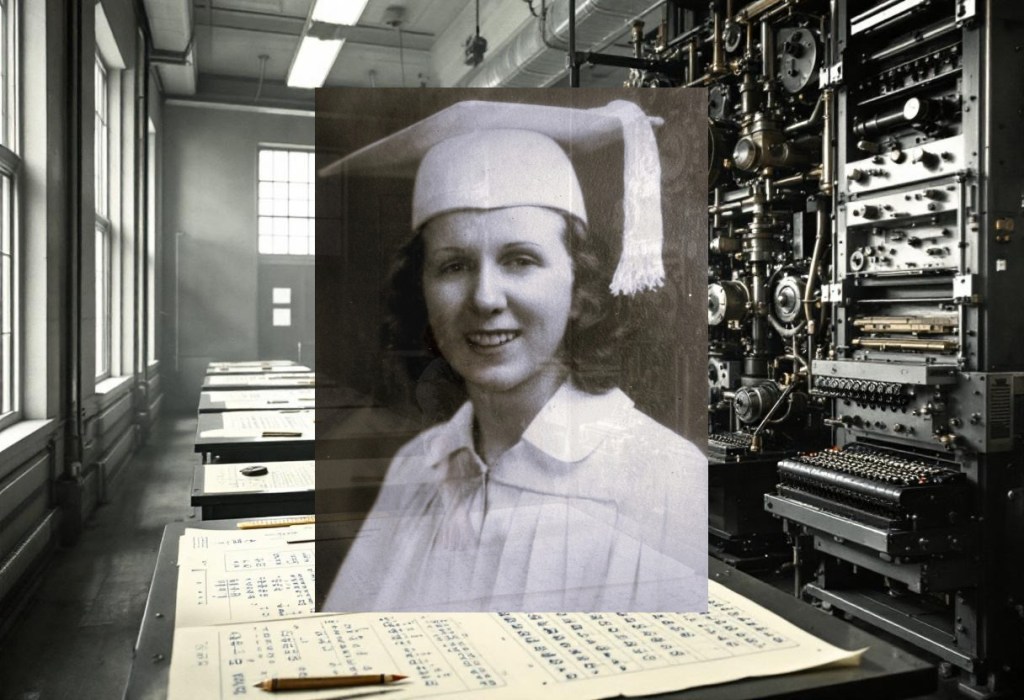

It is an immense honour to be sitting here with you, Mrs. Antonelli. Looking at the photographs from 1946, one sees a young woman with bright, intelligent eyes standing next to a behemoth of wires and vacuum tubes. For decades, the captions labelled you a “model,” but we now know you were the architect of the logic running through those cables. To sit across from the woman who looked at a mess of hardware and saw the future of software is a privilege. Welcome.

Thank you. Though, if you’d told me back in Philadelphia that people in 2025 would be fussing over “Kay McNulty from Donegal,” I’d have laughed you out of the room. We were just doing a job, you see. The Army needed trajectories, and we had the math. That was the start and end of it, or so we thought.

It was certainly more than just a job. You essentially invented the discipline of programming before the word really existed. I want to understand the mind that made that leap. How did a girl from Creeslough end up staring at the schematics of the ENIAC?

It started with the math. It always does. My mother spoke only Irish Gaelic until she was quite old, but numbers… numbers are the same in any language. When I came to America in 1924, I had to learn a new tongue, but math was a constant.

By the time I was at Chestnut Hill College, I took every mathematics course they offered. When the war came, the Army was desperate. They didn’t have enough men to calculate the firing tables for the artillery in Europe. So, they hired “computers.” Human computers. I sat in a room at the Moore School with a mechanical desk calculator – a Marchant or a Monroe – calculating differential equations by hand.

That sounds incredibly tedious.

Tedious? It was gruelling. To get one trajectory, you had to calculate the position of the shell every tenth of a second. It took about thirty to forty hours of human labour to calculate one trajectory. And the Army needed thousands. We were drowning in numbers. Then, we heard whispers about a machine. “Project X.” They said it could do in seconds what took us days.

And that was the ENIAC. But you weren’t allowed in the room with it initially, were you?

Oh, heavens no. We didn’t have security clearance for the hardware. Can you imagine? They handed us these massive blueprints – wiring diagrams of the panels – and said, “Here, figure out how to make it calculate the trajectory.”

We had to program the machine without touching it. We had to visualise the electricity. We’d crawl around on the floor with these giant sheets of paper, tracing the lines. “If pulse A goes into accumulator 4, and the switch is set to alpha, where does the carry bit go?” We were debugging hardware in our heads.

You are credited with inventing the subroutine. For the experts reading this, could you walk us through how you derived that concept on a machine that wasn’t designed for stored programs?

Well, you have to understand the architecture. The ENIAC wasn’t a stored-program computer in the way you have today. It was a parallel processor. To “program” it, you had to physically cable connections between different units – accumulators, multipliers, the master programmer unit.

The problem we hit was capacity. The master programmer had a limited number of steppers – essentially counters that controlled the sequence of operations. We were running out of space to tell the machine what to do next.

We were calculating a trajectory, right? You have the main integration loop – calculating velocity, air resistance, gravity – step by step. But occasionally, you need to do a specific, repetitive calculation that doesn’t fit in the main flow, or you need to reuse a set of instructions.

I realised we could use the “master programmer” unit to jump. Instead of wiring the same sequence of instructions three times and using up all our cables, I wired a sequence – let’s call it Sequence A. Then, I set up a stepper to divert the program flow to Sequence A, let it run, and then – and this was the trick – wire it to jump back to where it left off in the main sequence.

It was a loop within a loop. A nested hierarchy. We didn’t call it a “subroutine” then. We just called it “saving cabling.” But it meant we could do calculations that were theoretically too big for the machine, simply by reusing the logic circuits. It was about folding the time of the calculation into the physical space of the machine.

That is a profound conceptual shift – moving from linear calculation to non-linear logical structures. Did you realise at the time that you were creating the foundation of software architecture?

No. We were just trying to get the answer right. If the trajectory was off by a decimal point, a shell lands on our boys instead of the enemy. That was the pressure. We weren’t thinking about philosophy; we were thinking about precision. Discretising the differential equations was the only goal.

Let’s talk about the “public face” of this work. The ENIAC demonstration in February 1946. You had programmed the demonstration trajectory, but you weren’t introduced as the programmer.

That day… it was a spectacle. The press was there. The Generals. The big polished floor. The machine was humming – it made a terrible racket, you know, fans buzzing, tubes clicking.

Betty (Snyder Holberton) and I had spent the night before getting the program to run. It was a trajectory for a shell taking 15 seconds to hit its target. The ENIAC did it in 20 seconds. It was actually faster than the shell itself.

But when the cameras clicked, the men – Pres Eckert, John Mauchly, the Army officers – they stood in the front. We were told to stand by the panels and “act as hostesses.” Make sure the switches looked right. Smile. Don’t look too technical.

I remember a photographer shouting, “Step aside, ladies, we need a shot of the machine.” We were the ghosts in the machine. The irony is, without us, that machine was just a collection of expensive lightbulbs. It wouldn’t have calculated two plus two without our cabling.

That erasure persisted for decades. Do you feel a sense of bitterness about that?

Bitterness eats you up. I didn’t have time for it. I had five children. I had a life. But… yes, there was a sting. Especially when I married John [Mauchly].

The rules were different then. Anti-nepotism. Once I married the boss, I had to resign. I was at the peak of my ability. I knew the BINAC and the UNIVAC designs better than almost anyone. But a wife couldn’t work for her husband. So, I went home. I traded differential equations for diapers.

I don’t regret my family. I loved John. But I sometimes wonder what else I could have built if I hadn’t been forced to choose between a life and a career.

You mentioned the UNIVAC. You worked on the logic design for that as well, correct? How did the transition to stored-program computers change your approach?

Oh, it was a dream. With ENIAC, if you made a mistake, you had to physically trace a wire through a forest of cables. With UNIVAC and the C-10 code, we were writing symbols. Logic became language.

But I’ll tell you a mistake I made, something I learned the hard way. On the BINAC, we were testing a routine for square roots. I was so sure of my logic on paper. I had checked it three times. But when we ran it, the machine hung. Just stopped.

I had forgotten that the machine’s timing wasn’t perfect. There was a latency in the mercury delay line memory. I was treating the computer as a pure mathematical abstraction, but it was a physical object. It took time for a pulse to travel. I learned then that you cannot divorce the software from the hardware. You must respect the machine’s physical reality.

That is a lesson we are re-learning today with quantum computing and silicon limits.

Is that so? Well, physics always wins in the end.

Today, in 2025, things have changed. There is a building named after you at Dublin City University. The Irish supercomputer is named “Kay.” You are celebrated as a pioneer. What does that recognition mean to you, looking back from here?

It’s strange. Growing up in Donegal, the height of success was maybe owning a shop or marrying a doctor. To think my name is on a supercomputer? It feels… distinct.

But what matters more to me is that girls know they belong in that room. When I was at Moore School, the idea of a woman engineer was a joke to some. We were “computers” – a sub-professional grade.

I hope when young women see my name, they don’t just see a “pioneer.” I hope they see a worker. Someone who showed up, did the math, and didn’t let the fact that she was the only one in a skirt stop her from plugging in the cable.

Is there a specific piece of advice you would give to a young programmer working today – perhaps someone struggling with “Imposter Syndrome” or feeling marginalised in their lab?

Don’t wait for permission.

They didn’t give us permission to learn the ENIAC. They gave us diagrams and told us to figure it out. If I had waited for someone to invite me to the table, I would have died waiting.

And document your work! We didn’t write enough down. We were too busy doing it. If you invent something, put your name on it. Don’t let them call you a “hostess” later.

Kathleen, thank you. Your work is the reason we are having this conversation. The digital world is built on the subroutines you devised.

You’re very welcome. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I believe there’s a cup of tea waiting for me. And perhaps a look at this “Python” language everyone keeps talking about. It seems awfully verbose compared to a plugboard, doesn’t it?

Letters and emails

Since the publication of this interview, we have received hundreds of letters and emails from readers across the globe – mathematicians, programmers, historians, and those simply moved by Kathleen Antonelli’s story. Many wanted to ask her more: about the technical choices she made, the road not taken, the wisdom she might offer to those inheriting her legacy. We have selected five particularly thoughtful contributions, each offering a different lens through which to view her work and influence. These questions come from practitioners and scholars in Nigeria, Brazil, Sweden, New Zealand, and South Korea – a reflection of how her story resonates far beyond the Moore School’s laboratories and into the present day.

Ngozi Okoro, 34, Software Engineer, Lagos, Nigeria

You mentioned that timing in hardware – the latency of mercury delay lines – taught you that software cannot be divorced from physics. Today, we build software for devices with wildly different processing speeds and memory architectures, from smartphones to cloud servers. When you were designing logic for UNIVAC, how did you think about portability? Did you ever imagine a future where the same algorithm would need to run on machines with fundamentally different constraints, and if so, how would you have approached that problem differently?

Hello, Miss Okoro. That is a fine question, and it brings a smile to my face to think of a woman in Lagos wrestling with the same logic we pinned to the drawing boards in Philadelphia.

To be honest with you, the idea of ‘portability’ – lifting a program from one machine and dropping it into another without so much as a hiccup – would have seemed like magic to us. Or madness. You have to remember, in those early days, the machine wasn’t just a container for the code; the machine was the code. When we worked on the ENIAC, the program existed in the physical cabling. If you wanted to move that logic to another machine, you’d have to pack up the cables in a crate and ship them!

But when we got to the UNIVAC and the BINAC, things began to shift. We were working with stored programs then, instructing the machine through magnetic tape and mercury delay lines. Now, you ask if we thought about running that logic on different machines. In a way, my husband, John Mauchly, was obsessed with that very notion. He saw that we were wasting terrible amounts of time translating human mathematics into machine language – into the zeros and ones.

John came up with something called ‘Short Code’ for the BINAC. It was a grand idea: let the mathematician write the equations in a form that looked like algebra – something human – and let the machine do the translation work itself. That was the seed of your portability, I suppose. We wanted to separate the thought from the wire.

However, in practice? Lord, we were tied to the clock. On the UNIVAC, the memory was liquid mercury. Sound waves travelled through tubes of mercury to store the data. You had to know exactly how long it took for a pulse to travel from one end of the tank to the other. If your instruction arrived a microsecond too early or too late, you missed your data. We called it ‘latency optimisation,’ but really it was just patience.

So, when I wrote a routine, I wasn’t thinking, ‘Will this run on a faster machine in ten years?’ I was thinking, ‘Will this catch the pulse before it evaporates?’ We were knitting the logic to the bones of the specific machine we sat in front of.

If I could go back, knowing what you know? I think I would have spent less time worrying about saving memory – we were always so miserly with storage, counting every bit – and more time helping Betty Snyder. She was the one, you know, who really saw the future of languages that could speak like people. She used to say we shouldn’t have to be engineers to use a computer. I might have told her, ‘Betty, you’re right. Let’s stop optimising for the mercury and start optimising for the mind.’

But we did what we had to do to get the answer. It’s a comfort to know that while the machines have changed beyond recognition, the logic – the pure thinking of it – is the one thing that travelled well.

Björn Lindqvist, 41, Computer Historian, Stockholm, Sweden

Here’s a counterfactual that haunts me: what if you hadn’t been forced to resign after marrying John Mauchly? What if anti-nepotism rules hadn’t existed? Where do you think computing architecture would be today if you’d remained at the centre of the field through the 1950s and 1960s, rather than stepping back? Do you believe your particular way of thinking about nested logic and memory constraints would have shaped the industry differently?

It is a haunting question, as you say, Mr. Lindqvist. A ‘what if’ that sits in the corner of my mind now and then, usually when the house is quiet.

You have to understand, in 1948, the rules weren’t just written in company handbooks; they were in the air we breathed. A wife didn’t work for her husband. It was seen as… improper. As if I were taking a salary out of his pocket, or worse, that he couldn’t provide for me. The pressure to step back wasn’t just a policy; it was the polite thing to do.

But if I had stayed? Well, I was right there when we moved from the physical plugboards to the instruction codes – what you call software now. My mind was always on the economy of the machine. I hated waste. I hated seeing a vacuum tube idle when it could be calculating.

In the 1950s, as the memories got larger and the machines faster, the programming got a bit… sloppy, if I may be so bold. People started relying on the hardware to bail them out. They stopped counting the cycles. If I had remained at the desk, I think I would have been the one standing there with a red pen, insisting on elegance. The subroutine wasn’t just a trick to save cabling; it was a philosophy. Keep it tight. Keep it modular. I might have pushed for libraries of trusted code – standard pieces you could pull off the shelf – much earlier than they came about.

And I would have backed Betty Holberton to the hilt. She stayed, you know. She fought for the user, creating the sort-merge generator and making the languages easier to read. If I had been there, maybe we could have made the systems more accessible sooner.

But the biggest difference might not have been in the code at all. By the 1960s, programming was becoming ‘software engineering’ – a serious business, and therefore, in the eyes of the world, a man’s business. If I had stayed, if people had seen Mrs. Mauchly running the software side while Mr. Mauchly ran the hardware, maybe the young men in suits wouldn’t have been so quick to push the women out. We might have held the door open a little longer for the girls coming up behind us. That is the part that stings, just a little.

Luiza Silva, 29, Numerical Methods Researcher, São Paulo, Brazil

As a human computer, you performed numerical integration by hand using differential analysers. Now we have automatic differentiation and symbolic computation tools that do this work instantly. But I wonder – does the fact that you felt the mathematics in your hands, that you understood integration as a physical process with mechanical gears, give you an intuition that modern programmers trained only on abstractions might lack? Do you think there’s something lost when the mathematics becomes too invisible?

Miss Silva, you have hit upon something that I often think about, usually when I see young people trusting a calculator the way a priest trusts a prayer book.

You ask if we lost something when the math went invisible? I believe we did. Before the electronic machines, we had the Differential Analyser at the Moore School – Dr. Vannevar Bush’s design. It was a mechanical beast, all shafts and gears and torque amplifiers. To solve a differential equation, you didn’t just write it down; you built it with wrenches. And to run it, you had to stand at the plotting table and turn a hand-crank to keep a pointer right on the curve of the function.

If the curve spiked – if the rate of change was sudden – you had to spin that crank for dear life to keep up. You could feel the equation in your shoulder. You knew the derivative was steep because your arm was tired! You developed a physical respect for the behaviour of the numbers.

When we moved to the ENIAC, and later the UNIVAC, we gained speed, but we lost that sensation. The lights would blink, and the answer would spit out. But is it the right answer?

When you calculate a trajectory by hand, step by step, filling in those giant sheets of paper we used, you see the error accumulating. You notice if a value drifts. You develop a ‘nose’ for it. You look at a number and say, ‘That doesn’t look sensible.’

My worry for the modern scientist, sitting in front of those lovely screens, is that when the machine gives you a result instantly, you are too polite to question it. You accept it. We couldn’t afford to accept it. We had to verify everything because the machines were temperamental.

So, I would say to you: do not let the tool make you lazy. Once in a while, take a simple problem and work it out with a pencil. See the steps. Remind yourself that the computer is not a magic box; it is just a very fast clerk. If you don’t understand the work you are handing the clerk, you won’t know when he has made a mess of it.

Jun-Seo Kim, 37, Hardware-Software Co-Design Engineer, Seoul, South Korea

You invented the subroutine as a workaround – a way to fold time into space because the machine ran out of cabling. It makes me wonder: how many of the fundamental techniques we now teach as “best practices” in computer science were actually born from constraint and necessity rather than theoretical elegance? Do you think the constraints of your era produced better problem-solvers, or would you have preferred the freedom that modern abundance of memory and processing power offers?

Mr. Kim, you have hit the nail right on the head. We didn’t have the luxury of ‘best practices’ back then. We barely had practices at all! We were making it up as we went along, usually because we had hit a brick wall and needed a way over it.

You talk about the subroutine being a workaround. That is exactly what it was. On the ENIAC, we had these units called ‘steppers’ in the Master Programmer panel. There were only a handful of them. If your problem was complex – like a shell trajectory that changed depending on the air density at different altitudes – you ran out of steppers long before you ran out of math.

So, the invention wasn’t born from sitting in an armchair and thinking about beautiful logic. It was born because I looked at the panel and said, ‘We have run out of holes to plug the wires into.’ We had to fold the logic back on itself, or the machine simply couldn’t do the job. It was like packing a suitcase for a long trip when you only have a small bag; you learn to fold your clothes very tightly.

Do I think constraint produces better problem-solvers? I do. I truly do. When you have infinite space and infinite speed, you can afford to be sloppy. You can write code that goes all around the houses to get to the neighbour’s front door. But when every vacuum tube is precious – and liable to blow out if you look at it cross-eyed – you learn to cut to the bone. You learn to find the most elegant, direct path to the solution because you cannot afford the weight of anything else.

My mother in Donegal used to say, ‘Waste not, want not.’ It was true in the kitchen, and it was true on the ENIAC.

Now, would I have preferred your modern abundance? Oh, don’t get me wrong – I would have given my right arm for a bit more memory on the BINAC! It was terribly frustrating to have a grand idea and nowhere to put it. But I worry that with all this freedom, you lose the discipline of the craft. It is easy to build a mansion when you have unlimited bricks, but it takes a real master to build a castle out of a few stones.

Aroha Cooper, 26, Ethics in AI, Wellington, New Zealand

You said that a shell landing on “our boys” instead of the enemy kept you precise. There was a moral clarity to that work – the stakes were literal and visible. Now, algorithms designed by teams like mine shape loan approvals, hiring decisions, and content moderation. The stakes are distributed and often invisible. As someone who understood the weight of precision, what would you say to programmers today who might not feel the same responsibility for the accuracy and fairness of their code?

Miss Cooper, this question has kept me awake at night more than once. You speak of stakes that are distributed and invisible, and that terrifies me more than I can properly say.

When we were calculating those trajectories, yes, the stakes were brutally clear. A shell that lands ten meters off course because of a rounding error – that is a boy who comes home, or doesn’t. You could hold that weight in your mind. It made you careful. It made you sacred about your work, almost. You weren’t just pushing buttons; you were holding lives in your hands.

But your world, Miss Cooper – algorithms deciding who gets a loan, who gets hired, whose face gets flagged – that is a different kind of responsibility, and perhaps a more dangerous one because it is so easy to hide behind the machine.

I have thought about this a great deal. When I was forced to leave my work, one of the hardest things was knowing that the problems I had been wrestling with would go to someone else. But at least there was a person. At least you could find them and say, ‘Why did you make that choice?’ With your algorithms, who do you blame? The machine? The programmer who wrote the code five years ago and has moved on to something else?

Here is what I would tell any young programmer, man or woman: you must remember that your code is not abstract. It is not pure mathematics floating in some ethereal realm. It is going to touch real people. It is going to change the course of their lives. That is not a burden to be borne lightly.

When I was a human computer, calculating by hand, I understood that. Every number mattered. But as the machines got faster and the systems got more complex, I worry that understanding got lost. You start thinking of your work in terms of ‘efficiency’ and ‘optimisation,’ and you forget the person on the other end.

If you are designing an algorithm that approves or denies a loan, you must ask yourself: ‘Would I want this rule applied to my mother?’ If the answer is no, then you have not finished your work. You must do better.

The moral clarity I had – that came from proximity to consequence. You may not have that same clarity in your world of distributed systems and invisible stakes. So, you must manufacture it yourself. You must insist on knowing the impact of your code. You must ask hard questions of the people who want to use your work. And when you discover that your beautiful algorithm is harming people, you must have the courage to say so, even if it means your project is cancelled.

That courage is harder to find than clever code. But it is infinitely more valuable.

Reflection

Kathleen Antonelli passed away on 9th April 2006, at the age of eighty-five, having lived long enough to see the first tremors of recognition – the induction into the Women in Technology International Hall of Fame in 1997, the growing awareness of the ENIAC programmers’ contributions through Kathy Kleiman’s documentary work in the 1990s. Yet she did not live to see Dublin City University name a computing building in her honour in 2017, or Ireland’s national supercomputer christened “Kay” in 2019. She could not have known that a plaque would be unveiled in her native Creeslough in 2023, or that her story would be told to audiences across the globe nearly two decades after her death.

What strikes one most forcefully in conversation with Kathleen Antonelli – even in this imagined exchange – is her refusal of sentimentality. She did not frame her erasure as tragedy; she framed it as fact. She did not demand apologies for being told to “act as a hostess”; she observed it with the same precision she brought to differential equations. This measured tone, this Irish reserve paired with unflinching clarity, offers a counterpoint to many recorded accounts that have cast her as a victim of history. Antonelli was not passive in her erasure; she was actively sidelined, yet she speaks of it without melodrama. That distinction matters.

The historical record contains gaps. We know less about her specific technical contributions to BINAC and UNIVAC I than we do about her ENIAC work, largely because those systems operated within commercial secrecy and were documented less thoroughly by historians. Her own recollections – about the mercury delay line timing problem, about the hand-cranking of the differential analyser, about Betty Holberton’s vision for user-friendly languages – fill some of those gaps, but they also remind us how much has been lost to time and institutional forgetting. What subroutines did she develop that were never published? What design decisions were made in conversation with her that were credited to others? We may never know.

What we do know is that her core insight – that constraint breeds ingenuity, that visibility and recognition are prerequisites for retention in technical fields – remains urgently relevant. Today’s conversations about the “leaky pipeline” in STEM often focus on recruitment: getting more girls into computing, more women into engineering programmes. Antonelli’s story reframes the problem. The pipeline does not leak at recruitment; it leaks at recognition and retention. A woman can be brilliant, can invent foundational techniques, can hold the future in her hands – and still be invisible. The anti-nepotism rule that forced her resignation was not aberrant; it was policy, enforced, normalised. In her era, marriage was a trap that snapped shut.

The modern world has moved beyond such explicit rules, yet echoes persist. Women in software engineering report feeling pressure to choose between motherhood and advancement. Women in academic computing struggle for first authorship. Women in AI are underrepresented in leadership despite their foundational contributions to the field. The mechanisms have changed; the outcome has not shifted as much as we might hope.

Antonelli’s legacy was rescued and amplified by Kathy Kleiman’s ENIAC Programmers Project, which began in the 1990s as an oral history effort and has grown into a profound scholarly and cultural intervention. It was sustained by journalists, historians, and archivists who refused to let the erasure be permanent. It was honoured by Ireland’s investment in naming its supercomputer after her – a deliberate act of national reclamation, acknowledging a brain drain that had sent so many Irish minds across the Atlantic, now being symbolically repatriated through a machine that bears her name.

What Antonelli might say to young women entering computational fields today is what she said to Aroha Cooper: ask hard questions, manufacture moral clarity when it is not given to you, and refuse to let the complexity of modern systems excuse you from responsibility. Do not wait for permission. Document your work. Put your name on it. Do not let them call you a hostess later.

But perhaps more importantly, she offers a model of persistence without bitterness, of precision without fanfare, of caring deeply about the work while remaining unsentimental about recognition. She loved mathematics as one loves a language – not for praise, but for the clarity it brings. She invented the subroutine not to change history, but to solve an immediate problem. History changed anyway.

That quiet refusal to perform brilliance for applause, combined with an absolute refusal to accept invisibility – that is the spark she leaves behind. It is a reminder that the foundations of the digital age were laid by women whose names we are still learning, and whose ingenuity continues to run beneath every algorithm, every subroutine, every line of code executed on devices that would have seemed like miracles to the girl from Donegal who once cranked a hand-operated differential analyser in the basement of the Moore School.

The subroutine she invented is executed billions of times every second across the planet. Her thinking lives in the logic of every modern program. And now, finally, so does her name.

Editorial Note

The interview transcript presented here is a work of thoughtful fiction, grounded in historical fact but structured as an imaginative reconstruction. Kathleen Antonelli passed away in 2006 and cannot speak for herself in real time. However, this dramatised conversation draws upon extensive documented sources: her published interviews and articles, oral history recordings from the ENIAC Programmers Project, biographical accounts, technical documentation, and historical scholarship about her life and work.

What has been preserved with fidelity are the core facts of her biography, her technical achievements, the institutional barriers she faced, and the documented statements she made about her experiences. Her voice, tone, and phrasing have been crafted to reflect period-appropriate language, her Irish background, and the measured, precise manner in which she was known to discuss her work – but this is an interpretive reconstruction, not a transcript.

The dialogue with the interviewer is entirely constructed. The five supplementary questions and answers are similarly imagined, though they respond thoughtfully to genuine tensions and questions that scholars, practitioners, and historians continue to grapple with regarding her legacy.

This reconstruction serves a specific purpose: to humanise and centre Antonelli’s perspective in a historical moment when she was systematically silenced, and to make her technical and philosophical insights accessible to contemporary readers in a conversational form. It is not a substitute for her actual words or primary sources. Readers seeking her authentic voice are encouraged to consult the ENIAC Programmers Project archives, her published reflections in computing journals, and the scholarly works cited within this piece.

The aim is not to deceive, but to illuminate – to restore, through careful imagination grounded in evidence, a presence that institutional erasure attempted to erase. In doing so, we acknowledge both what we know with certainty and the gaps that remain, honouring Kathleen Antonelli’s memory whilst being honest about the limits and nature of this reconstruction.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment