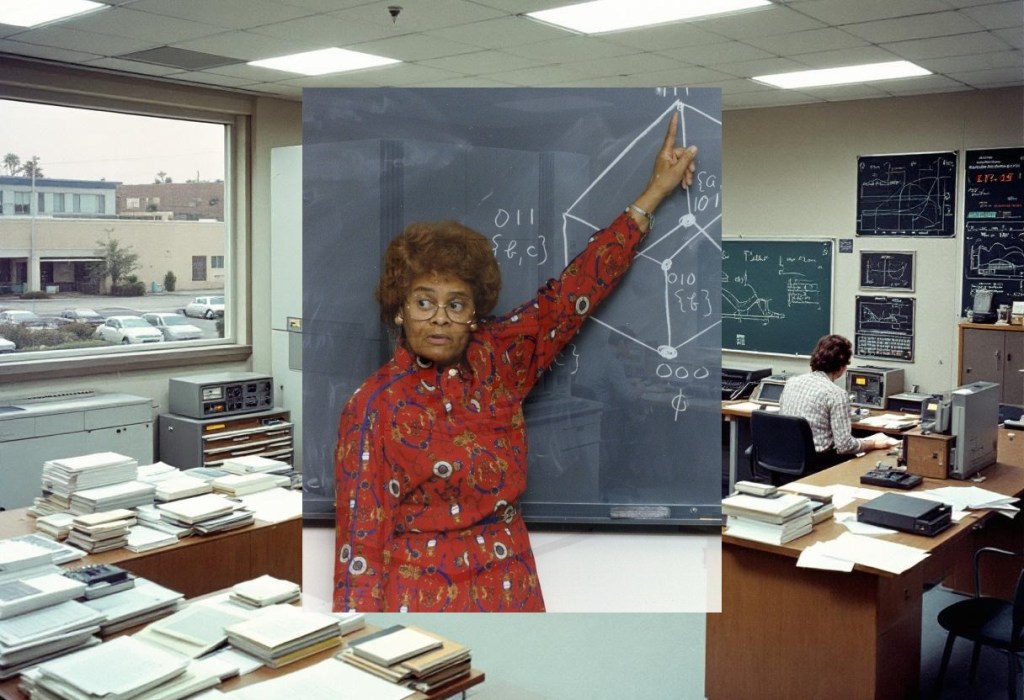

Evelyn Boyd Granville (1924–2023) was the second African-American woman to earn a doctorate in mathematics from an American university, receiving her PhD from Yale University in 1949 – a distinction that placed her among perhaps a handful of Black women mathematicians in the entire world at that moment. Born in segregated Washington, D.C., during the Great Depression and educated at the rigorous, historically Black Dunbar High School, she went on to master both the theoretical abstractions of functional analysis and the practical minutiae of early computer programming, becoming an architect of the computational methods that guided spacecraft to the moon and back. Today, as we mark the hundredth anniversary of her birth and confront the ongoing underrepresentation of Black women in mathematics and science, her life – lived across the pivotal transformation from human calculators to digital computers – illuminates not only what was possible even under conditions of profound exclusion, but what remains possible if we choose to see it, support it, and build institutions that welcome it.

Dr Granville, thank you for speaking with us today. I’d like to begin where your own story began – in segregated Washington, D.C., during the Depression. What was it about that time and place that shaped a mathematician?

Well, you must understand that segregation, for all its cruelty and unfairness, didn’t prevent education – it concentrated it, in a way. My mother and aunt raised me with the firm conviction that education was the one thing no one could take from you. At Dunbar High School, we had teachers who were themselves highly educated, many of them from Howard University. There was no lowering of standards because of our race; if anything, the opposite. We were expected to know our Euclid, our algebra, our history – all of it, thoroughly.

I remember Mrs. Anita Turley, my geometry teacher. She had this way of asking questions that made you think you’d discovered the answer yourself, rather than being told it. “Why must this be true?” she’d ask. Not “learn this rule,” but “why does nature arrange itself this way?” That’s what drew me to mathematics – the logic, the inevitability of it. Once you understand why, the anxiety disappears.

That’s a striking contrast to how mathematics is often taught – as a series of procedures to memorise rather than truths to understand. Did you feel, even then, that this education was unusual?

I didn’t have a comparison point at the time, did I? I simply knew that my school was excellent, and I worked hard. It wasn’t until I arrived at Smith College that I understood what segregation had actually cost – not in the quality of my teachers, but in the assumptions people made about me. I was one of very few Black students there, and I could see it in some faces: surprise that I could do the work, or worse, a kind of corrective intensity, as if they had to prove I belonged by scrutinising me more carefully than anyone else.

How did you do that?

By working harder than I needed to. Perhaps that wasn’t the wisest choice, but it was my choice. I graduated summa cum laude, majors in mathematics and physics. I wanted there to be no question, no asterisk, no “well, for a Negro girl” attached to my accomplishment. I see now that I may have taken that burden onto myself, but I also refused to let it defeat me. That distinction matters.

You went to Yale for your doctorate, where you studied functional analysis under Einar Hille. That was an extraordinary opportunity in 1946. How did that happen?

Yale wasn’t my first choice for graduate school, if I’m honest. I would have preferred Princeton, but… Princeton didn’t accept women into their doctoral mathematics programme at that time. Yale would take me, and Einar Hille was interested in my work. So Yale it was.

Hille was a rigorous, demanding scholar – Swedish, very precise. He expected you to think clearly and write clearly, and he had no patience for vagueness. My dissertation was on Laguerre series in the complex domain, which sounds rather abstract, I suppose, but it was absorbing work. The question was: how do these orthogonal functions behave when you extend them into the complex plane? What properties persist, and what breaks down?

Can you explain that in a way that a trained mathematician but non-specialist might understand?

Imagine you have a tool that works perfectly well on the real number line – say, a thermometer that measures temperature from zero to one hundred degrees. Now imagine trying to use that same thermometer in an imaginary space where temperature is, say, the square root of negative one. The thermometer doesn’t make intuitive sense anymore, but mathematically, the question remains: does the underlying physics still hold? Do the relationships still describe something true?

Laguerre polynomials are a family of functions with beautiful properties in the real domain. They’re orthogonal, which means they’re perpendicular to each other in a functional sense. They’re used in quantum mechanics, in solving differential equations. I was investigating what happens to these relationships when you introduce complex arguments – when you allow the input to be complex numbers rather than just real ones.

The work was intricate, involving contour integration and careful analysis of singularities. It’s the sort of mathematics that lives entirely in the abstract realm, and I confess I loved it. After Yale, I thought that would be my career – teaching and research in pure mathematics.

But it wasn’t. What shifted?

Reality, I suppose. I taught at NYU and then at Fisk University. Both were good institutions, but I began to feel – how shall I put it? – a certain restlessness. I was interested in functional analysis, yes, but I was also profoundly interested in things that worked, that solved real problems. At Fisk, I mentored two young women, Vivienne Malone-Mayes and Etta Zuber Falconer, both brilliant mathematicians who would go on to earn their own doctorates. That work – recognising potential and opening doors – was satisfying in a way that pure research, conducted in isolation, was not.

And then I began to hear about the new electronic computers. IBM had built the 650, and I thought: here is applied mathematics on a scale I’ve never considered. The chance to take theoretical insights and translate them into something that could actually compute, that could solve real-world problems – that was compelling.

Did the mathematicians around you support that transition, or did it feel like leaving the “true” work behind?

There was a certain… perception that applied mathematics was less rigorous, less intellectually demanding than pure theory. That was incorrect, but the perception was real. Some colleagues were supportive; others saw it as a step down, a compromise. I had to be comfortable with that judgment against me, because I wasn’t making the choice to satisfy them. I was making it to satisfy myself – to do work that interested me, that had consequences I could trace.

You joined IBM in 1956. Describe that transition for us – what was computer programming in 1956?

It was barely a profession, really. There were no textbooks, no established best practices, no university programmes teaching it. There were brilliant people – many of them women – who had worked as “computers” during the war, doing calculations by hand or on mechanical calculators. We human computers knew numerical methods intimately. We understood where errors crept in, how to structure calculations to minimise them. When electronic computers arrived, we had to learn a completely new language.

I learned assembly language on the IBM 650 first – SOAP, which stood for “Symbolic Optimum Assembly Program.” It was exacting work, writing in machine code essentially, thinking about every operation the computer would perform. You had no margin for error; you had to anticipate what the machine would do with your instructions.

Then FORTRAN came along – Formula Translating System – and it was revolutionary. John Backus and his team at IBM created a compiler that would translate mathematical notation into machine code. Suddenly, you could write something that looked almost like mathematics and have the computer translate it. But the art of programming wasn’t just writing the formula; it was understanding how to break down a problem into discrete, sequential steps that a machine could execute, how to handle precision and rounding, how to test whether your code was actually producing correct answers.

You moved into aerospace work at North American Aviation and U.S. Space Technology Laboratories. What was the leap from programming the IBM 650 to calculating spacecraft trajectories?

A rather substantial one, I suppose. But the mathematical principles were the same. When you’re calculating a satellite orbit or a spacecraft trajectory, you’re solving differential equations – the equations of celestial mechanics that date back to Newton and Lagrange. Given an object’s current position, velocity, and the gravitational forces acting on it, you predict where it will be at the next moment in time. You do this in small increments, step by step, integrating the equations of motion forward in time.

On paper, this is elegant. In practice, it requires millions of calculations, each one dependent on the previous one. A single rounding error, repeated through thousands of steps, could accumulate and send your spacecraft in the wrong direction. That’s where programming expertise was critical. We had to write code that was not merely correct in principle, but stable in practice – that handled precision carefully, that anticipated numerical problems before they became catastrophes.

Can you walk us through a specific example – say, calculating the trajectory for Vanguard?

Vanguard was the first American satellite we successfully orbited in 1958. The challenge was something called the “two-body problem,” which is rather simpler than what we’d later face with Apollo, but it’s illustrative.

You begin with initial conditions: the satellite’s launch position, its velocity vector – the direction and speed at which it leaves Earth. You know Earth’s mass and thus the gravitational field it creates. You know you want the satellite to enter a stable orbit – a specific altitude where the gravitational pull exactly balances the centrifugal effect of its motion.

Now, here’s where programming comes in. The equations of motion are:

d²r/dt² = −GMm/r²

That is: the acceleration of the satellite equals the gravitational force divided by its mass. In components, you have equations for x, y, and z motion. These are coupled, nonlinear differential equations with no closed-form solution for arbitrary orbits. You must integrate numerically.

We’d use a method called Runge-Kutta integration – fourth-order Runge-Kutta, if we had the computing resources – where you estimate the satellite’s position and velocity at each small time step Δt. After each step, you recalculate the gravitational acceleration based on the new position, then advance to the next step. After thousands or tens of thousands of steps, you trace out the complete trajectory.

The precision requirements are stringent. We typically worked to better than one part in a million. An error of one metre over a 150-kilometre orbit seems small until you realise the satellite is moving at eight kilometres per second; that one-metre error represents a timing difference of a tenth of a second, which could mean missing the orbital window entirely.

What were the practical techniques you used to manage that precision?

Double precision arithmetic was critical – using more bits to represent each number, carrying more decimal places. The IBM 704, which we used for Apollo calculations, gave us about fifteen significant digits of precision. We’d validate our code constantly by solving test problems where we knew the answer – simple elliptical orbits, for instance – and comparing our numerical solution to the analytical one. If there was divergence, we’d trace through the code to find where it arose.

We also built in error bounds and sanity checks. Does the total energy of the system remain conserved? It should, mathematically. If the code was producing trajectories where energy increased or decreased mysteriously, that was a sign of numerical instability. We’d rewrite sections, try different integration schemes, adjust time steps.

And we’d manually verify calculations. That’s something often overlooked. The computer did the brute-force arithmetic, but humans reviewed the results. I personally would spot-check calculations, work through sections by hand, ask: does this trajectory make physical sense? A computer can produce an answer; it can’t tell you whether that answer is reasonable.

That collaborative relationship between human mathematical intuition and machine calculation – that must have been unusual for the time.

It was essential, not unusual. John Glenn, when he was preparing for his Mercury mission, specifically asked that Katherine Johnson verify the electronic computer’s calculations by hand. The machines were new; trust had to be earned. We human computers didn’t disappear when electronics arrived; we evolved. We became supervisors of the machines, interpreters of what they told us, quality controllers. Our mathematical training allowed us to ask whether a result was plausible, and when it wasn’t, we knew where to look for the problem.

Your most significant work came during Apollo. What was that environment like?

Urgent. Absolutely urgent. President Kennedy had announced we were going to the moon before this decade was out, and the entire aerospace industry mobilised around that goal. North American Aviation, where I was working in my later years, was the contractor for the Apollo Command and Service Module. There was no room for error – not because anyone would be casually forgiving of mistakes, but because astronauts’ lives depended on the calculations.

We were working on mission planning, trajectory analysis, re-entry dynamics. When an Apollo spacecraft comes back from the moon, it must hit a very narrow window – called the “corridor” – upon re-entry. Too steep an angle, and the spacecraft burns up in the atmosphere. Too shallow, and it skips off the atmosphere like a stone on water and doesn’t come back at all. The window is perhaps a few hundred kilometres wide and a few tens of kilometres in altitude. Miss it by much, and three men die.

How narrow was “the corridor” in practical terms?

On the order of half a degree in entry angle. We’d calculate the trajectory from lunar orbit all the way through Earth re-entry, taking into account gravitational effects from both the moon and Earth, atmospheric drag modelled as accurately as we could manage, variations in Earth’s mass distribution. The computer would run for hours – literally hours – to produce a single mission profile. Then we’d review it, check boundary conditions, look for numerical instabilities. If anything troubled us, the entire calculation might be redone.

The re-entry problem was particularly intricate because the atmosphere isn’t a simple fluid; it has layers with different densities and temperatures. Below a certain altitude, you transition from free molecule flow – where individual air molecules strike the spacecraft – to continuum flow where you can treat air as a bulk fluid. The equations of motion change across that transition. You have to handle both regimes correctly, or your trajectory prediction breaks down entirely.

Did you ever find errors in previous calculations? Mistakes that could have had serious consequences?

Not catastrophic ones, but yes. Small things – rounding errors that had accumulated in older hand calculations, assumptions that seemed reasonable but didn’t hold under specific conditions. I remember one instance where re-entry heating calculations were overestimated because the model of atmospheric density at high altitude was slightly off. It was corrected before flight, but had it not been caught, the heat shield specifications would have been over-engineered, adding unnecessary mass, changing the performance characteristics of the spacecraft. Subtle errors in one domain ripple into others.

That’s why verification was so crucial. You couldn’t just run your code once and trust the output. You had to cross-check with multiple methods, had to ensure that independent teams arrived at the same answer, had to keep asking “what could go wrong here?”

There’s a curious disconnect, isn’t there? These calculations you and others performed were literally the difference between success and disaster, life and death. And yet much of this work went uncredited, invisible to the world.

The work itself was visible in the sense that the missions succeeded. Vanguard orbited. Mercury astronauts came home safely. Apollo reached the moon. But the people doing the work – particularly those of us who were contractors rather than NASA employees, and particularly those of us who were Black or women – our names simply weren’t recorded. You were a job title, a function. Your code was absorbed into the larger system. Your name didn’t appear on reports.

I won’t say it didn’t matter to me, because it did. Recognition has value beyond ego; it validates your existence in a field, it creates pathways for others like you. But I was aware that my invisibility was, in a sense, protection as well. I could do my work without the scrutiny that sometimes fell on others. I had perhaps a small degree of professional freedom because fewer eyes were watching.

That’s a poor recompense, ultimately. But it was real.

After Apollo succeeded, you returned to academia – California State University, Los Angeles, in 1967. Why?

I had been in applied mathematics and programming for over a decade. The work was challenging, yes, but I began to wonder about the future of mathematics education in this country. I’d seen bright young people, women particularly and Black students, turned away from mathematics by inadequate preparation or by being told, explicitly or implicitly, that they didn’t belong. I thought about Vivienne and Etta, my students at Fisk, and how much their success had depended on someone taking them seriously.

Also, I’ll be honest: the aerospace industry was beginning to phase out some of the programming work I’d been doing. More routine tasks were being handled by junior programmers or automated. I was no longer doing pioneering work; I was refining what had been pioneered. That’s important work, but it wasn’t calling to me anymore.

Teaching offered something different. You could shape minds. You could show a young person that mathematics was not a closed club, that their presence was wanted. You could design curricula that made sense, that built understanding rather than mere procedure. And you could do it at scale – reach hundreds of students, and through them, reach people you’d never meet directly.

What was it like, re-entering academia after being away from teaching for so long?

Refreshing and strange. The technology had advanced tremendously, but the pedagogy hadn’t in all cases. I was frustrated to see mathematics still taught as a set of rules to memorise, as my own education had not been. I pushed for applications – why are we learning this? Where does it arise? How would an engineer or physicist use it? Some colleagues thought I was lowering standards; I thought I was raising motivation.

I also became involved in curriculum development for elementary school mathematics. People think that’s unambitious work, but it’s not. Elementary mathematics is where the damage often occurs. A child who struggles with fundamental concepts, who internalises the belief that they’re “not a math person,” carries that wound forward. If we could reshape how mathematics is presented to young children – with curiosity and play and real-world connection – we could change trajectories.

Did you find that the aerospace work had changed how you approached teaching, or vice versa?

The aerospace work had taught me precision, rigour, and the consequences of mistakes. Teaching reinforced something I’d perhaps undervalued: the importance of clarity. In writing code for a spacecraft trajectory, clarity is means of survival. In teaching, clarity is means of liberation – it frees people from confusion, from the sense that they’re stupid when actually the material has simply been poorly explained. Both demanded that I think carefully about how to communicate complex ideas, but for different audiences. One was about saving lives through calculation; the other was about saving lives through education.

I want to address something directly. You were the second African-American woman to earn a doctorate in mathematics. Euphemia Haynes was the first, in 1943. Did you know her? Were you aware of that precedent?

I was aware of it intellectually, but we didn’t know each other personally. Euphemia was slightly older, and her path took her through different institutions. But knowing she existed, that someone had crossed that threshold before me – that mattered tremendously. It meant I wasn’t utterly alone in thinking this was possible. At the same time, the fact that only one woman had done it before me in the entire United States, and now there were two of us, speaks volumes about how closed this field was.

As you progressed through your career – at Yale, at IBM, at North American Aviation – did you encounter discrimination?

Of course I did. I encountered it daily in small ways and occasionally in large ones. Doors that didn’t open, meetings I wasn’t invited to, assumptions that I was there to support someone else’s work rather than do my own. There was also the question of advancement. As a woman in technical fields, you could move so far up and no further. Full professorship at a major research university would have been… unlikely. Possible, perhaps, but unlikely.

Being Black layered another dimension onto it. There were people who believed, sincerely, that I didn’t have the intellectual capacity for the work, that my accomplishments were a mistake or a consequence of lowered standards somewhere. Others were simply uncomfortable with my presence – not hostile, necessarily, but uncomfortable. They didn’t know how to interact with me, so they didn’t.

Did any of this make you want to leave the field?

Yes. There were moments – after a particularly dismissive conversation, or after being passed over for an opportunity I knew I was qualified for – when I thought about leaving. But I didn’t. And I ask myself now why. Was it stubbornness? Pride? A sense of obligation? Probably all of those things. But it was also that mathematics itself was not the problem. The racism and sexism I encountered were problems within the structure; they didn’t discredit the work itself.

Also, I was strategic about where I positioned myself. I chose contractors where there was less institutional gatekeeping, companies pursuing novel work where competence mattered more than whether I fit a particular mould. I chose to return to teaching at an institution – Cal State LA – that was expanding access to higher education, that had a mission I believed in. I wasn’t at Princeton or Harvard, but I was somewhere I could do meaningful work and contribute to broadening who got access to mathematics.

Why do you think your story remained hidden for so long?

Part of it is structural. I was a contractor; my name went on very few official reports. Another part is that I moved frequently – between institutions, between cities, between applied work and teaching. You build lasting visibility through institutional stability, and I didn’t have that in the way that creates a long record that historians stumble across. My papers weren’t collected and archived at one place. I wasn’t at one university for forty years where students could point to me as part of their lineage.

There’s also the reality that the space programme captured the public imagination in specific ways. We know the astronauts’ names. We know the mission names – Apollo, Mercury, Vanguard. We don’t know the names of the people who calculated their orbits. That’s partly a limitation of public attention, and partly a deliberate choice by institutions about whose stories get told.

And there was timing. My work was most visible in the 1960s, before the women’s movement reached full strength, before civil rights legislation actually changed institutional practices. It took the film Hidden Figures and the book, released when I was in my nineties, to bring public attention to this history. By then, much of my work was decades in the past, and much of it was in archives that required someone to care enough to look.

How did it feel to have your work suddenly become visible, even if late in your life?

It was… unexpected. Gratifying. Vindicating, in a way I didn’t anticipate I would need. But also tinged with something else – sadness, perhaps. Because I thought about all the people who had died without that recognition. I thought about the ways that recognition creates pathways for others, and what opportunities were lost because I remained invisible for so long. I thought about young Black girls who might have seen my work earlier and thought, “That could be me.” Instead, they had to wait decades.

I want to dive deep into the technical side of your most complex work. Let’s reconstruct a detailed trajectory calculation from Apollo. Walk us through the mathematical and computational challenges, step by step.

Right. Let’s take the trans-lunar injection – the burn that takes the spacecraft from Earth orbit to the moon. This is one of the most critical manoeuvres, because if you calculate the velocity and direction incorrectly, you might miss the moon entirely or arrive at the wrong time.

You start with the spacecraft in Earth orbit – let’s say 185 kilometres altitude, which was roughly the Apollo parking orbit. The spacecraft’s position vector from Earth’s centre is r₀, its velocity vector is v₀. You need to calculate the Δv – the change in velocity – required to escape Earth’s gravity and travel to the moon.

Now, this sounds simple: calculate escape velocity, apply the difference. But the moon is moving; you’re not aiming at where the moon is now, but where it will be when you arrive. This involves calculating the lunar orbit, predicting the moon’s position days in advance, then working backwards to determine what trajectory gets you there.

The fundamental equations are the equations of motion in the gravitational field:

d²r/dt² = −GMr/r³

where M is Earth’s mass and r is the position vector. This is simple enough on the page; computational nightmare in practice because it’s nonlinear.

You use numerical integration – specifically, we used Adams-Moulton methods for high precision. Here’s the algorithm:

You divide time into small steps of duration Δt. At each step n, you know the position rₙ and velocity vₙ. You calculate acceleration aₙ = −GMrₙ/|rₙ|³. Then you predict the next state:

rₙ₊₁ ≈ rₙ + vₙΔt + ½aₙ(Δt)²

vₙ₊₁ ≈ vₙ + aₙΔt

But this is just the predictor step. You then correct by recalculating the acceleration at the new position and iterating:

rₙ₊₁ = rₙ + ½(vₙ + vₙ₊₁)Δt

You repeat this predictor-corrector cycle until convergence. This minimises the error that accumulates with simple Euler stepping.

What were your typical time steps? And how did you handle the transition from Earth orbit to deep space?

Time steps depended on proximity to celestial bodies. Near Earth, during the parking orbit phase, we used steps of perhaps ten seconds. As the spacecraft accelerated and climbed away from Earth, distances changed more slowly, so we could lengthen to fifteen or twenty seconds. By the time we were halfway to the moon, we might be using thirty-second steps.

The transition is where you must be careful. As the spacecraft climbs from Earth orbit, it’s simultaneously falling toward the moon. At some point – roughly 90 percent of the way to the moon – lunar gravity dominates. Before that point, Earth’s gravity is the primary force; after, the moon’s is.

What you actually do is calculate the trajectory in the “restricted three-body problem” frame, where you have Earth, moon, and spacecraft, and you’re solving for the spacecraft’s motion under both gravitational fields. The equation becomes:

d²r/dt² = −GMₑrₑ/|rₑ|³ − GMₘrₘ/|rₘ|³ + other perturbations

where subscript e is Earth, m is moon. The “other perturbations” included the sun’s gravity, though its effect was small, and relativistic corrections, though for these velocities they were negligible.

The moon’s orbit isn’t perfectly circular; it’s elliptical. The moon’s position itself needs to be calculated – you propagate its position forward using its orbital elements or by numerical integration of its equations of motion. So you’re not just solving for the spacecraft; you’re solving for multiple bodies simultaneously.

How many orbits or iterations would a single trajectory calculation require?

For a trans-lunar injection to lunar orbit – roughly a three-day journey – we’d calculate in the region of perhaps ten to twenty thousand time steps per trajectory variant, depending on step size and precision. Each time step involved multiple iterations of the predictor-corrector method, vector arithmetic in three dimensions, and several function evaluations. That’s a lot of computation.

On the IBM 704, a full trajectory calculation from Earth to lunar orbit might take four to six hours of machine time. We’d run multiple variations – slightly different launch times, slightly different trans-lunar injection velocities – to find the optimal trajectory that minimised fuel consumption while ensuring safe margins.

And then you had to verify all of this?

Absolutely. We’d check energy conservation – the sum of kinetic and potential energy should remain constant in an isolated system. We’d verify that the trajectory passed through lunar orbit at the predicted epoch. We’d run test cases with known solutions. We’d compare our numerical results to closed-form solutions for simplified systems – purely two-body dynamics, for instance.

We’d also do what we called “backward integration.” You’d start with the predicted lunar arrival state and integrate backward in time using the same algorithm. If the code was correct, you’d arrive back at Earth orbit with the velocity and position you started with. Any drift indicated accumulated error.

That was a phenomenal check because it worked independently of whether the forward trajectory looked reasonable; the code itself had to be self-consistent.

What were the typical errors you’d encounter?

Rounding errors accumulated primarily. A single operation might lose a bit of precision; you’d repeat that operation tens of thousands of times, and small errors compounded. We’d also encounter instabilities with certain integration schemes if the time step was too large relative to the dynamics. The orbit has characteristic periods – an hour or two for a spacecraft circling Earth – and if your time step was too long relative to that, you’d skip over important features of the trajectory.

There were also modelling errors. We estimated atmospheric drag, but the atmosphere isn’t uniform and its density varies with solar activity. We had to use models, and models have uncertainty built in. Those uncertainties propagated into the trajectory prediction. That’s why we kept margins – we didn’t aim precisely at the moon’s position; we aimed with enough margin that small calculation errors wouldn’t result in catastrophe.

How much margin are we talking about?

At lunar orbit insertion – the burn that slows the spacecraft enough to be captured by the moon’s gravity – the velocity error needed to be kept to perhaps a few metres per second. A hundred-metre-per-second error might result in missing orbit insertion or arriving in an unsafe orbit. We wanted our trajectory predictions accurate to better than one per cent, ideally better than half a per cent.

That’s stringent. It requires careful coding, careful verification, and sophisticated numerical methods. This is why it took expertise to do this work – not genius, but genuine technical mastery of numerical methods, programming, celestial mechanics, and physical intuition about what could go wrong.

After you retired from Cal State LA in 1984, you remained active in education advocacy, particularly around mathematics and women in STEM. What drove that?

The statistics frustrated me deeply. Decades after I’d earned my PhD, Black women still comprised less than one per cent of mathematicians. Women overall were underrepresented at every level – undergraduate, graduate, faculty. And the quality of mathematics education at the elementary level was often appalling, particularly in under-resourced schools.

I began to travel, giving talks about mathematics education. I’d speak to teachers, to students, to parents. I’d bristle – I mean, I would actively object whenever anyone suggested that women couldn’t do mathematics. That’s nonsense. Women had been doing mathematics for centuries; they’d simply been written out of the histories.

I became interested in curriculum development and teacher training because I believed – and believe – that a child’s mathematics trajectory is largely determined by age twelve. If you haven’t developed confidence and foundational understanding by then, it becomes much harder to recover. So the investment should be early, and it should be in the quality of instruction.

Was there a particular moment when you committed to that work?

I think it was visiting a school in California and seeing bright eight-year-old children – predominantly Latino, predominantly from working-class families – who had been sorted into a “remedial” mathematics track, even though there was nothing wrong with their mathematical thinking. They’d simply had less exposure to formal mathematics at home, and the school had responded by giving them less rather than more. The waste of potential was staggering.

I thought about my own education – how Dunbar High School had assumed we were capable, had challenged us accordingly, and had created an environment where excellence was ordinary. What would these children’s lives look like if they’d had that? I wanted to try to create conditions where that was possible.

Looking back now, how do you assess the state of women in mathematics?

Better than when I started, but still inadequate. There are more women in mathematics now, certainly. More Black women. I’ve seen young mathematicians earning doctorates, becoming professors, doing groundbreaking work. That’s heartening.

But the underrepresentation persists. The barriers I encountered – social exclusion, assumptions about belonging, tracking and sorting that begins in childhood – these haven’t vanished. They’ve become more subtle in some ways, but they’re still there. And the culture of mathematics still tends to valorise certain styles of thinking – the brilliant individual working alone – over collaborative, applied, and pedagogical contributions.

I regret nothing of my career, including the applied work that some might have considered a step down from pure mathematics. That work had value, and it had impact. But I wish the field had been structured such that a Black woman could have remained in pure mathematics if she’d chosen, without it being treated as unusual or requiring such fierce determination. I wish more women had felt welcomed, treated as if they belonged from the beginning.

You received significant recognition late in your life – honorary doctorates, the Wilbur Lucius Cross Medal from Yale. How did that feel?

It was validating in a way I didn’t expect to need. When you’re working, living your life, you don’t think much about recognition. You’re focused on solving the problem in front of you. But late in life, to have institutions acknowledge your contributions – that carries weight.

What pleased me most was that it created a narrative. Young people could point and say, “This woman did this work, and it mattered.” The honours created what I wish I’d had when I was starting out: a visible role model, a story in the official record rather than in scattered archives.

I want to ask about things you might have done differently. Were there professional choices you made that, with hindsight, you’d approach differently?

I think I was perhaps too accepting of invisibility early on. I told myself it didn’t matter that my name wasn’t on reports, that I could do my work and let the results speak for themselves. But by not pushing to be visible, I may have made it easier for institutions to erase the contributions of women and people of colour more broadly.

I don’t entirely regret it – there was a kind of freedom in being overlooked – but I wonder if I should have been more insistent about claiming space, about documenting my own work, about making sure I wasn’t simply absorbed into someone else’s accomplishment.

Also, I perhaps spent too much energy trying to prove my capabilities to people who would never believe in them anyway. I took on the idea that I needed to work harder, know more, be more perfect than my colleagues to be considered equal. That’s a belief many women and minorities carry, and it’s exhausting. I wish I could tell my younger self: your work is sufficient. Your presence is sufficient. You don’t have to earn the right to exist in this space.

Were there moments when you doubted your mathematical abilities?

Of course. Everyone does. But I tried to distinguish between genuine uncertainty about a problem and self-doubt rooted in absorbed racism or sexism. When I was struggling with a piece of mathematics, I’d ask: is this difficult because it is genuinely difficult, or because I’ve been told I’m not smart enough for it? Usually, it was the former. The work was hard because it was hard, not because I wasn’t capable.

There was one instance – early in my programming work at IBM – where I wondered if I’d made a mistake leaving pure mathematics. The code wasn’t working, I couldn’t find the bug, and I thought maybe I wasn’t cut out for this applied work. But I sat with it, worked through it systematically, and found the error. It was a subtle off-by-one problem in a loop – something that could happen to anyone. After that, I never again questioned whether I belonged in applied mathematics.

Do you think the “Hidden Figures” narrative gets your story right?

The broad outlines, yes. The essential truths about the work we did and the barriers we faced. But like all narratives, it simplifies. It tends to present us – Black women mathematicians during the space race – as more unified in our experience than we were. Katherine Johnson’s story is different from mine in meaningful ways. Our institutional positions were different, our career trajectories diverged significantly. By grouping us under one heading, the narrative inadvertently erases some of that specificity.

Also, the focus tends to be on the most dramatic moments – the space race, the calculations that determined whether astronauts survived. That’s compelling, and it’s important. But it’s only part of the picture. My later work in education was less visible but, I’d argue, equally important in its long-term consequences. I tried to change systems so that future generations wouldn’t face the barriers I faced. That’s a different kind of legacy.

What would you want people to understand about that?

That recognition and credit matter not merely for ego, but because they create pathways. When people see that someone like them did mathematics, succeeded in physics, wrote software, they think, “Perhaps I can, too.” And institutions respond to visibility – if they see women and people of colour in a field, they’re more likely to create conditions for more to enter.

Conversely, erasure creates its own barriers. If the history of mathematics is written as a history of white men, and women of colour appear only as exceptions or anomalies, then young people from those groups absorb that message. They think they don’t belong. So the work of recovery – making sure that accurate histories are told – isn’t merely academic. It’s foundational to building fields that are actually open and welcoming.

If you could speak directly to young women, particularly young Black women, entering mathematics and science today, what would you say?

First: you belong here. Not conditionally, not if you try harder or know more than everyone else. You belong because you’re thinking, learning, contributing. Let no one convince you otherwise.

Second: mathematics is not a fixed set of procedures; it’s a way of understanding the world. The people who struggle most with mathematics are often those taught it as meaningless manipulation of symbols. But when you understand why something is true, when you see how it connects to problems you care about, mathematics becomes alive. Don’t let bad teaching convince you that you’re not a “math person.”

Third: you have choices about the kind of work you do and the environments where you work. Pure mathematics is valuable. Applied mathematics is valuable. Teaching is valuable. Industrial work is valuable. Don’t let anyone tell you that one path is more legitimate than another. Choose based on what compels you, what problems you care about, what you think you can contribute.

Fourth: seek out mentors, and when you have the opportunity, be a mentor. The fact that Vivienne and Etta earned doctorates mattered not just for them; it created a lineage. It meant there were now three Black women with PhDs in mathematics instead of one. Be conscious of that multiplicative effect of lifting others up.

And fifth: don’t accept invisibility as inevitable. Document your own work. Push for credit. Insist on being seen and named. It’s not selfish; it’s essential. Because without visibility, the next woman in your position will struggle just as you did. With visibility, she might have an easier path.

Do you have hopes for the next generation of mathematicians?

Many. I hope they’ll be less willing than my generation to accept erasure as the price of admission. I hope they’ll demand institutions that actually value diversity, not merely represent it. I hope they’ll remember that the abstract beauty of mathematics – which I loved deeply – exists in dialogue with the world, with problems that matter, with people who need solutions.

And I hope they’ll tell each other’s stories. Not just the famous ones, but the full record – the people who did brilliant, invisible work. The people who built infrastructure that others built upon. The people who taught and mentored and changed systems. Mathematics is not an individual sport; it never has been. We stand on each other’s shoulders. Acknowledging that doesn’t diminish any individual’s achievement; it enriches the whole enterprise.

Looking at the trajectory that took you from segregated Washington, D.C., through Yale, through IBM, through the Apollo programme, to education reform – what do you make of that arc now?

I didn’t plan it as an arc. I made choices step by step, responding to what interested me and what was available. In retrospect, there’s a certain logic to it – a movement from individual accomplishment through solving specific problems toward trying to change systems for everyone else.

But I want to be clear: I was given opportunities. My mother and aunt insisted on education. My teachers at Dunbar took me seriously. Smith College accepted me. Yale took a chance on me. IBM and North American Aviation hired me despite – or perhaps because – they weren’t as bound by conventional ideas about who could program computers. Those opportunities were rare, and I’m grateful for them.

What I want to change is that this shouldn’t be exceptional. The pathway should be open enough that talent finds it naturally, without requiring special circumstances. We lose so much potential by structuring our fields in ways that discourage participation from entire groups of people.

Thank you, Dr Granville. One final question: how would you like to be remembered?

As a mathematician who took her work seriously – whether it was abstract functional analysis or practical computer code. As someone who believed that excellence and inclusion are compatible, that you can demand rigour and kindness simultaneously.

And perhaps as someone who understood that mathematics isn’t merely abstract symbols; it’s a language for understanding the world and intervening in it. Whether you’re calculating the path of a spacecraft or designing curriculum for children, you’re doing mathematics with purpose. That’s how I tried to live – with the conviction that my work could matter, that it could contribute to something larger than myself. I hope that comes through.

Letters and emails

Following the publication of this wide-ranging conversation with Dr Evelyn Boyd Granville, we received an extraordinary response from readers and researchers across the globe. Mathematicians, engineers, educators, and science advocates wrote to us with questions they wished they could pose to her – queries that emerged from their own work, their own struggles, and their own curiosity about the connections between her era and ours.

What became clear through this correspondence was that Dr Granville’s life and work continue to speak across disciplines and borders. Her story resonates not only with those in mathematics and computing, but with anyone navigating fields where excellence and belonging have been treated as competing rather than complementary values. Her insights into the translation between theory and application, between individual contribution and institutional change, address challenges that persist in research and education worldwide.

We selected five letters and emails from our growing community – contributors based in Asia, Africa, Europe, South America, and North America – each bringing a distinct perspective shaped by their professional context and geographical location. These questions move beyond the main interview, probing technical details that weren’t fully explored, pressing gently on philosophical tensions she navigated, and inviting her to imagine counterfactuals and offer counsel to those now walking the paths she helped forge.

What follows are those five questions, posed directly to Dr Granville, along with the names and locations of those who asked them. Their inquiries reflect a community determined to learn not just what she accomplished, but how she thought, what sustained her, and what wisdom she might offer to scientists and mathematicians confronting their own versions of the barriers she faced.

Thao Nguyen (34, Software Engineer and Mathematics Education Advocate, Ho Chi Minh City, Asia)

You mastered both SOAP assembly language and FORTRAN – languages built on fundamentally different principles. SOAP required you to think in terms of individual machine operations, whereas FORTRAN allowed you to express mathematics more directly. When you transitioned between them, did your approach to problem-solving shift? And looking at modern languages like Python, which abstract away even more complexity, do you worry we’ve lost something about understanding how computation actually happens?

What an astute observation, Thao. You’ve put your finger on something I’ve thought about a great deal over the years – the relationship between the language you use to instruct a machine and the way you conceptualise the problem itself.

When I learned SOAP on the IBM 650, you were working extraordinarily close to the metal, as they say now. You had to think about drum memory addresses, about the specific sequence of operations the machine would execute, about optimising for the limited storage we had available. The 650 had a magnetic drum that rotated – physically rotated – and if you weren’t careful about where you placed your instructions and data, the machine would waste precious milliseconds waiting for the drum to come round to the right position again. So you’d arrange your code spatially, thinking about the physical geography of storage. It was rather like arranging furniture in a room to minimise walking distance.

That discipline – thinking through every single step the machine would take – trained you to be precise in a way that’s difficult to describe. You couldn’t be vague. You couldn’t wave your hands and say “and then we do the calculation.” You had to specify: load this value from address 0045 into the accumulator, add the value from address 0046, store the result in address 0047, branch to address 0050 if the result is negative. Every. Single. Step.

When FORTRAN arrived – and I remember the excitement when we first saw what John Backus and his team at IBM had created – it felt almost magical. You could write something like Y = A * X**2 + B * X + C and the compiler would translate that into dozens of machine instructions. You didn’t have to think about drum addresses or accumulator operations; you could think in mathematical notation.

Now, did my approach to problem-solving shift? Yes and no. The fundamental mathematical structure of what I was doing didn’t change. Whether I was writing in SOAP or FORTRAN, I was still breaking a trajectory calculation into differential equations, still choosing an integration method, still worrying about numerical stability and accumulated error. But the level at which I was thinking changed.

In SOAP, I had to hold two mental models simultaneously: the mathematics I was trying to implement and the machine operations that would execute it. In FORTRAN, I could focus more on the mathematics and trust the compiler to handle the translation. That freed up cognitive resources. I could tackle more complex problems because I wasn’t spending mental energy on low-level bookkeeping.

But – and this is where your concern about modern languages becomes relevant – there was a danger in that abstraction. If you didn’t understand what the compiler was doing, you could write code that looked correct mathematically but performed terribly or produced subtle errors. Early FORTRAN compilers weren’t always efficient; sometimes they’d generate dozens of unnecessary operations. If you didn’t understand that, you might write code that took hours to run when it should have taken minutes.

I always insisted on knowing what was happening beneath the surface. Even when writing in FORTRAN, I’d occasionally look at the assembly output to see what the compiler had generated. I wanted to understand whether my code was actually doing what I thought it was doing.

Now, you mention Python and the concern that we’ve lost something. I think that’s a legitimate worry, though perhaps not quite in the way some people frame it. The danger isn’t abstraction itself – abstraction is essential; it’s how we manage complexity. The danger is abstraction without understanding, treating the computer as a magical black box rather than a machine following explicit rules.

I’ve seen students – bright students, mind you – who can write Python code that produces an answer, but when you ask them what the computer is actually doing, they have no idea. They don’t understand floating-point representation, so they’re baffled when 0.1 + 0.2 doesn’t exactly equal 0.3. They don’t understand algorithmic complexity, so they write code that works perfectly on small test data but grinds to a halt on real problems. They treat packages like NumPy or SciPy as incantations – import the right spell and get the right answer – without understanding what algorithms those packages are running or whether they’re appropriate for the problem at hand.

That troubles me because computational mathematics isn’t just about getting an answer; it’s about getting the right answer, knowing why it’s right, and understanding the limitations and uncertainties involved. When trajectory calculations for Apollo were being verified, we didn’t just check that the code ran; we checked that the numerical methods were stable, that precision was adequate, that physical principles like energy conservation were satisfied. We understood our tools deeply because lives depended on it.

But I don’t think the solution is to force everyone back to assembly language. That would be rather like insisting medical students manufacture their own scalpels before learning surgery. The tool and the craft aren’t the same thing.

What I would advocate – and what I tried to implement in my teaching – is layered understanding. Students should learn high-level languages like Python because that’s where they can express mathematical and algorithmic ideas clearly. But at some point in their education, they should also learn what’s happening underneath: how numbers are represented in binary, how memory works, why some operations are fast and others slow, what numerical stability means in practice.

They should be taught to question their results. Does this answer make physical sense? If I run the calculation twice with slightly different starting conditions, do I get similar answers or wildly divergent ones? If the latter, that’s a sign of numerical instability or chaos, and I need to understand which and why.

In my own work, the progression from SOAP to FORTRAN didn’t diminish my problem-solving capability; it enhanced it, precisely because I retained the understanding I’d gained from working at the lower level. I could think at a higher level of abstraction while still being grounded in the reality of what the machine was doing.

So to answer your question directly: yes, my approach shifted – I could work faster, tackle more ambitious problems, think more naturally in mathematical terms. But the discipline of precision, the habit of questioning whether the computer was really doing what I intended, the awareness that abstraction is a convenience not a substitute for understanding – all of that remained.

I think modern students need both. They need the power and expressiveness of contemporary languages, absolutely. But they also need, at least once in their education, to write code at a low enough level that they viscerally understand that computation is a physical process, that numbers in computers are approximations, that algorithms have costs, and that the machine does exactly – exactly – what you tell it to do, not what you meant it to do.

That understanding, once acquired, stays with you. And it makes you a better computational scientist, regardless of what language you’re writing in.

Paulo Montenegro (52, Aerospace Engineer and History of Technology Scholar, São Paulo, South America)

The re-entry corridor you described – half a degree of entry angle separating survival from disaster – seems almost impossibly narrow. Modern spacecraft have guidance systems that can correct trajectory in real time. In your era, the entire mission profile had to be calculated before launch with no mid-course corrections. What was your safety margin philosophy? How much redundancy did you build into the calculations, and how did you decide between making trajectories more fuel-efficient versus more forgiving of small errors?

Paulo, you’ve identified one of the most consequential engineering challenges we faced during Apollo – and one where the mathematics had to be absolutely bulletproof because there was no margin for improvisation once the spacecraft had left Earth orbit.

You’re correct that the re-entry corridor was brutally narrow. We were aiming for an entry flight path angle of roughly minus 6.5 degrees relative to the local horizontal at the entry interface – which we defined as 400,000 feet altitude, about 122 kilometres. If you came in steeper than about minus 7.2 degrees, the deceleration loads and heating would exceed what the spacecraft and crew could survive. If you came in shallower than about minus 5.5 degrees, you’d skip off the atmosphere – bouncing back into space with insufficient velocity to return, or entering a highly elliptical orbit with no fuel left to correct it. Either way, the crew would be lost.

That half-degree tolerance I mentioned? That’s the difference between life and death, calculated over a trajectory that began a quarter of a million miles away at the moon.

Now, your question about safety margin philosophy – that gets to the heart of how we approached mission planning, and it wasn’t a simple answer because we were balancing multiple constraints simultaneously.

First, fuel efficiency. Every kilogramme of propellant we could save was a kilogramme we could allocate to scientific instruments, life support reserves, or structural margins elsewhere. The spacecraft had a finite fuel budget, and Apollo was already pushing the limits of what the Saturn V could lift. So there was enormous pressure to optimise trajectories for minimum fuel consumption.

But second, and more important, was crew safety. We had to ensure that even if things went wrong – if an engine underperformed slightly, if the trajectory deviated because of navigation errors, if the atmospheric density wasn’t exactly what we’d modelled – the crew would still come home alive.

The way we handled this was through what we called “dispersions analysis.” We didn’t just calculate the nominal trajectory – the ideal path assuming everything went perfectly. We calculated hundreds of trajectories with perturbations: what if the trans-Earth injection burn was one per cent low? What if it was half a degree off-angle? What if the atmospheric density at re-entry altitude was ten per cent higher than predicted? What if the spacecraft’s centre of mass was slightly off, affecting its aerodynamic characteristics?

For each perturbation, we’d propagate the trajectory forward and see where the spacecraft ended up. If too many of those dispersed trajectories fell outside the safe corridor, we’d redesign the nominal trajectory to be more forgiving – perhaps targeting the centre of the corridor rather than the fuel-optimal edge of it, or building in an extra mid-course correction opportunity.

We’d also look at what we called “Monte Carlo” runs, where we’d randomly vary multiple parameters simultaneously – navigation errors, thrust variations, atmospheric uncertainties – and run thousands of simulated missions to see what percentage resulted in safe returns. We wanted something like 99.9 per cent of the dispersed cases to fall within acceptable bounds.

Now, the fuel-efficiency question becomes interesting because it wasn’t just about the total fuel budget; it was about where you spent your fuel. A mid-course correction burn halfway back from the moon was much cheaper, in terms of delta-v, than trying to correct your trajectory during re-entry. If you were slightly off course at the midpoint, a small burn – maybe five or ten metres per second of velocity change – could put you back on the correct path. But if you waited until you were nearly at Earth, the correction would cost far more fuel, and by the time you hit the atmosphere, you had no fuel-based correction capability at all. You were committed to whatever trajectory you’d arrived on.

So our philosophy was this: design the nominal trajectory to be robust, with the spacecraft naturally tending toward the centre of the safe corridor. Build in scheduled mid-course correction opportunities – typically two or three during the return from the moon – where the crew could refine their trajectory based on actual navigation data. And budget enough fuel for those corrections assuming reasonably probable deviations from nominal, not best-case scenarios.

For the re-entry itself, we also exploited the spacecraft’s aerodynamic properties. The Apollo Command Module wasn’t a perfect sphere; it had a centre of mass offset from its geometric centre, which meant it generated lift when flying through the atmosphere. The crew could control the direction of that lift by rolling the spacecraft. This gave them a limited ability to steer during re-entry – not to correct major trajectory errors, but to fine-tune the final landing point and manage heating loads.

We’d calculate what we called the “entry corridor footprint” – the range of possible landing locations depending on where within the corridor you entered and how you flew the lifting entry. The crew had been trained to fly specific roll profiles to stay within thermal limits and hit the target landing zone, but they also had some discretionary authority to modify that profile if necessary.

The heating question you raised is critical because it wasn’t just about peak temperature – it was about total heat load integrated over time. Come in too steeply and you’d get very high peak heating rates that could exceed the heat shield’s capacity. Come in too shallow and you’d be in the atmosphere longer, accumulating total heat even if the peak rate was lower. There’s an optimal trajectory that minimises peak heating, and we’d bias toward that within the constraints of hitting the landing zone.

To give you concrete numbers: the Apollo heat shield was designed to handle peak heating rates of about 400 British thermal units per square foot per second – that’s roughly 4.5 megawatts per square metre in contemporary units. The ablative material – a phenolic resin compound – would char and vaporise, carrying heat away. We had to ensure that in all reasonably probable scenarios, including off-nominal entries, we stayed below that limit with margin.

Our safety margins were typically expressed as “three-sigma” tolerances – meaning we designed for conditions three standard deviations away from nominal, which statistically should cover 99.7 per cent of cases. But we’d also look at worst-case combinations: what if multiple things went wrong simultaneously? What if the navigation error was at the edge of tolerance and the atmosphere was unusually dense and the spacecraft’s mass was slightly higher than expected? We wanted the mission to survive even some very improbable combinations of failures.

I should also mention that we had abort modes planned for various phases of the mission. If something went seriously wrong during trans-lunar coast, there were trajectories calculated that would loop around the moon without entering lunar orbit and return directly to Earth – what we called “free return trajectories.” Apollo 13, as you know, used exactly such a trajectory after their oxygen tank explosion. That option existed because we’d calculated it in advance and because the nominal mission profile was designed such that switching to the abort trajectory was possible with the fuel remaining.

Now, did we always achieve the perfect balance between efficiency and safety? No. There were debates – sometimes heated ones – between mission planners who wanted more margin and spacecraft designers who needed to save mass. I remember discussions where engineers advocated for carrying extra fuel for mid-course corrections, and others argued that the mass penalty of that extra fuel would force us to reduce the lunar stay time or carry fewer experiments.

In the end, the fact that we brought every Apollo crew home safely – including Apollo 13 under catastrophic circumstances – suggests we got the balance approximately right. But I won’t pretend it was comfortable. Every mission, we were aware that we were betting astronauts’ lives on our calculations being correct, on our models being adequate, on our margins being sufficient.

The difference between your modern spacecraft with real-time guidance and our era is profound. You can measure where you actually are, compare it to where you should be, and correct continuously. We had to predict where the spacecraft would be days in advance, commit to a trajectory, and trust that our physics was right, our numerical methods were stable, and our safety margins were adequate.

That’s why verification was so crucial, why we ran so many dispersed cases, why we checked and rechecked our calculations. We were flying on mathematics – on the belief that if we modelled the physics correctly and computed carefully, nature would behave as our equations predicted.

And it did. Every time, it did. But I’ll tell you honestly, Paulo: I never watched a launch or a re-entry without holding my breath, without running through the calculations in my mind one more time, without praying that we hadn’t missed something. The mathematics was sound, the margins were real, but the consequences of error were absolute.

That’s the weight that comes with computational work in aerospace. Your code doesn’t just produce answers; it determines whether people live or die. You carry that responsibility differently than you carry academic research, and it shapes how carefully you work, how thoroughly you verify, and how much margin you insist upon even when others are pressing you to optimise just a little bit more.

Selam Awate (28, Physicist and Science Policy Researcher, Addis Ababa, Africa)

You spent decades doing work that saved lives – calculating trajectories that brought astronauts safely home – yet received no public recognition until near the end of your life. Many of us in Africa and the Global South work on problems with immediate human stakes but little institutional visibility. How did you maintain conviction in the value of your work when the world wasn’t watching? And what would you tell young scientists in under-resourced regions who wonder if their contributions matter if they’re not published in prestigious venues or celebrated in the media?

Selam, your question moves me deeply, and I want to answer it with the honesty it deserves. You’ve asked something that I think many of us – those working far from the centres of power and prestige – have wrestled with quietly, sometimes in the middle of the night when the doubts creep in.

How did I maintain conviction when the world wasn’t watching? I’m not sure I have a satisfying answer, because truthfully, there were days when I didn’t maintain it. There were evenings when I’d come home from work and think: what am I doing this for? My name isn’t going on reports. My colleagues at other institutions don’t know I exist. If I disappeared tomorrow, would anyone notice beyond my immediate supervisor needing to find someone else to write the code?

But then morning would come, and I’d return to work, and I think what sustained me through that cycle was something my mother and aunt instilled in me from childhood: the work itself has worth, regardless of who’s watching. They raised me during the Depression, when simply surviving with dignity was an accomplishment, when you couldn’t afford to wait for external validation because it might never come. You did what needed doing because it needed doing, because you had the capacity to do it, and because refusing to do it would diminish you more than being ignored by others did.

That sounds perhaps more noble than it felt at the time. The reality was often more mundane: I enjoyed the work. Solving a trajectory problem, debugging a piece of code, figuring out why a numerical method was unstable – these gave me satisfaction independent of recognition. The mathematics was elegant. The programming was like solving puzzles. And I knew – I knew – that what I was calculating would be used, that it would contribute to missions that everyone would see, even if they didn’t see me.

There’s a particular kind of satisfaction in doing essential work that others depend upon. The astronauts’ lives depended on trajectory calculations being correct. It didn’t matter whether my name was attached to them; what mattered was that they were right. And when Apollo 11 landed on the moon and returned safely, I felt a fierce, private pride. I had been part of that. My code had contributed to that. The world didn’t know it, but I knew it, and that knowledge had its own weight.

But I want to be honest with you, Selam, because I think you and others working in under-resourced regions deserve honesty more than platitudes: the lack of recognition did have consequences. It meant I couldn’t leverage my work to advance my career the way others could. When you’re invisible in the official record, you can’t use your accomplishments as credentials for the next position. You can’t point to your contributions and say, “I did this significant thing.” You’re starting fresh each time, having to prove yourself again.

It also meant isolation. When your work isn’t published, you’re not part of the scholarly conversation. You don’t attend conferences where people know your research. You don’t have colleagues at other institutions building on your methods or citing your results. You exist in a kind of professional solitude, and that’s exhausting over time.

So how did I manage it? Partly through stubbornness, I suppose. A refusal to let other people’s failure to see me determine my own sense of worth. Partly through finding satisfaction in the work itself rather than in its reception. And partly – I’ll be frank – by eventually changing the terms of engagement. I left aerospace and returned to teaching, where the impact was more immediate and visible. You could see students understand a concept, watch them gain confidence, help them imagine futures they hadn’t thought possible. That feedback was tangible in a way that trajectory calculations weren’t.

Now, you’ve asked what I would tell young scientists in under-resourced regions who wonder if their contributions matter if they’re not celebrated by prestigious institutions. Here’s what I believe:

First, the work matters if it’s solving real problems for real people. You don’t need a journal publication to validate that clean water calculations are important, that agricultural yield predictions help farmers, that epidemiological models protect communities. If your work has local impact – if it makes people’s lives better, safer, healthier – then it matters profoundly, regardless of whether anyone in London or New York or Geneva notices.

The Western academic system has convinced us that only work published in high-impact journals, only research conducted at elite institutions, only science that gets international attention has value. That’s rubbish. It’s a story told by people at those institutions to maintain their own centrality. Some of the most important science happening in the world is being done by researchers whose names I’ll never know, solving problems I’ll never hear about, in communities I’ll never visit. That work is no less real because it’s not in Nature or Science.

Second, document your work anyway. Even if you can’t publish in prestigious venues, write it down. Keep detailed records. Share it with colleagues in your region. Build local networks of researchers working on similar problems. The international system may not see you, but that doesn’t mean you have to remain invisible to each other. Some of the most productive scientific communities in history were quite local and regional before they gained broader recognition.

Third, think carefully about what success means to you. Is it recognition from distant institutions that don’t understand your context and won’t support your work? Or is it making genuine contributions to problems you care about, in places you care about, for people you know? I’m not saying you shouldn’t want international recognition – I wanted it, and I’m glad I eventually received some – but I am saying that you can’t let its absence paralyse you or make you believe your work is worthless.

I spent decades doing work that had enormous impact with almost no recognition. Was that fair? No. Did it limit my opportunities? Absolutely. But would I trade those years for having done nothing because I couldn’t do it on terms the prestigious institutions would acknowledge? No, I wouldn’t. Because the work was real, the contributions mattered, and I knew – even when no one else did – that I was capable, competent, and making a difference.

Fourth – and this is important – be strategic about when and how you seek recognition. There are times to work quietly, building your capabilities and track record. And there are times to be more assertive about documenting and sharing your work, about connecting with broader networks, about claiming credit. I was perhaps too accepting of invisibility early in my career, and I regret that somewhat. If I could do it again, I might be more insistent about my name appearing on reports, about my contributions being acknowledged, about creating a paper trail that historians could later find.

You don’t have to choose between doing good work and being visible. Ideally, you do both. But if you’re forced to choose – if the system makes you choose – then do the good work. Because in the long run, work that actually helps people, that solves real problems, that advances understanding in meaningful ways, that work has a way of mattering even when it’s not initially celebrated.

Finally, remember that institutional prestige is often a lag indicator. The institutions that are prestigious now became that way because of work done decades or centuries ago, often by people who were marginalised at the time. The future centres of scientific excellence may well be in places that current power structures ignore. Your work – done in Addis Ababa or Nairobi or Accra, addressing problems specific to your context with methods appropriate to your resources – that work may be building foundations that others will recognise as essential decades from now.

I lived long enough to see some recognition of the work I’d done fifty years earlier. That was gratifying, but it was also bittersweet, because I thought about all the people who did similar work and died before anyone acknowledged it. I thought about all the young people who might have entered science if they’d known people like them had contributed to great achievements.

So my advice, Selam, is this: do work you believe in, work that serves people and problems you care about. Document it carefully, even if you can’t publish it in prestigious venues. Build networks with others doing similar work in similar contexts. Be strategic about seeking recognition when opportunities arise, but don’t let its absence stop you from working. And remember that impact and prestige are not the same thing – sometimes they align, but often they don’t, and when forced to choose, I’d rather have impact.

Your contributions matter because they address real needs, because they represent your best thinking applied to genuine problems, and because science is bigger than any single institution or publication or award system. The universe doesn’t care whether your results appear in a famous journal; it simply is what it is, and understanding it better – wherever that understanding comes from – is valuable.

Keep working, keep documenting, keep connecting with others. The world may not be watching now, but the work remains real, and its value doesn’t depend on external validation. That’s what I learned across decades of invisibility, and it’s what eventually allowed me to keep contributing even when the recognition seemed like it might never arrive.

Trevor Langston (46, Mathematics Educator and Historian of Computing, Boston, North America)

In the interview, you mentioned bristling whenever people suggested women couldn’t do mathematics. But you also described taking on pressure to work harder and prove yourself – which is a different burden than simply being told you’re incapable. How do you hold both of those experiences simultaneously? And as you built your later curriculum work with young people, particularly those from underrepresented backgrounds, did you try to protect them from that absorbed pressure, or did you think some of it was necessary to instil rigour and determination?

Trevor, you’ve asked a question that gets at something I’ve spent years trying to understand about myself, and I’m not sure I have a fully satisfying answer even now. You’re right that there’s a tension there – a real one – between the defiance I felt when told women couldn’t do mathematics and the internalised pressure I placed on myself to exceed expectations. Those two things coexist, and they’re not contradictory; they’re actually two sides of the same coin.

Let me try to untangle this. When someone told me – explicitly or through their scepticism and surprise – that women couldn’t do mathematics, I had a visceral reaction. It made me angry. It felt like a lie, because I was doing mathematics, and I was doing it competently. The anger came from the injustice of it, the falseness of it, the arbitrary gatekeeping. I would bristle – yes, that’s exactly the right word – because I was contradicting the claim by my mere existence. My presence was defiance.

But that defiance came with a cost, which was the pressure I put on myself. If I was going to be evidence that women could do mathematics, then I couldn’t do it adequately – I had to do it brilliantly. I couldn’t be average; I had to be outstanding. Because if I was merely competent, people could say, “Well, perhaps she’s an exception, but that doesn’t prove women in general can do mathematics.” But if I was genuinely excellent, that argument became harder to make.

So I internalised a crushing standard. I worked harder than my male colleagues because I believed – and perhaps I was right – that my work would be scrutinised more carefully, questioned more readily. If there was an error in my calculations, it wouldn’t be seen as a mistake that any human might make; it would be seen as evidence of female incapacity. I carried that burden without fully articulating it to myself, but it was there, shaping every choice I made.

Was that burden necessary? I don’t think so. Looking back now, I think some of it was real – there genuinely were people who would judge my work more harshly because of my race and gender – but much of it was self-imposed. I was internalising the prejudices of others and then exceeding them on my own, which is a peculiar kind of slavery. I was doing the oppressor’s work for them, setting standards for myself that no one had actually demanded.

Now, when I moved into teaching, particularly when I was working with young people, I had to make a choice about whether to pass that burden on or to try to protect students from it.

I didn’t protect them entirely – I don’t think that would have been wise – but I tried to be intentional about it in a way I wish someone had been with me.