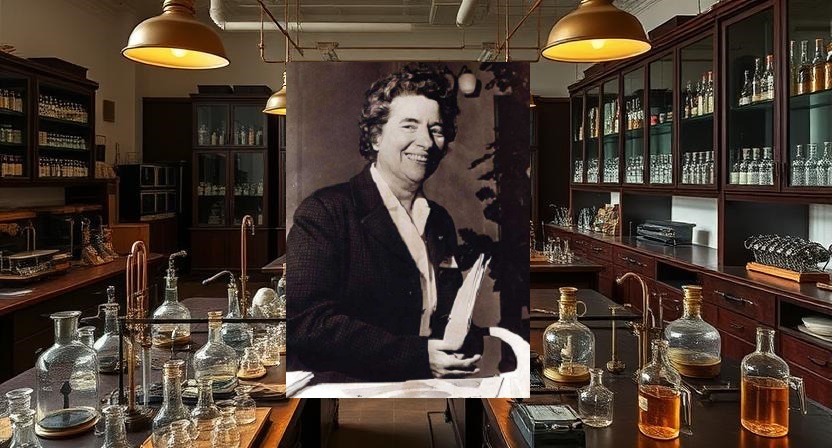

Marguerite Perey discovered francium, the final naturally occurring element on the periodic table, in 1939 whilst working as Marie Curie’s personal assistant at the Radium Institute in Paris. Despite lacking formal university credentials, she became the first woman elected to the French Académie des Sciences in 1962, an honour denied to her celebrated mentor. Tragically, her groundbreaking work with radioactive materials would ultimately cost her life, as she died from radiation-induced bone cancer in 1975.

Marguerite Perey’s discovery of francium represents one of the most significant achievements in early nuclear physics, yet her contribution was initially overshadowed by institutional barriers and safety practices that were criminally inadequate. Her meticulous isolation of this highly radioactive alkali metal required extraordinary precision, working with samples so minute that today’s laboratories would contain fewer than ten million atoms at a time. The bitter irony of her career lies in francium’s potential medical applications – she hoped it might diagnose cancer, only to have the very element she discovered ravage her own body with the disease she sought to combat.

Today, Perey’s legacy reverberates powerfully with contemporary discussions about laboratory safety, gender equality in scientific institutions, and the ethical responsibilities we bear when pursuing dangerous research. Her story serves as both an inspiration for women breaking barriers in nuclear science and a sobering reminder of the human cost of scientific progress without proper protection protocols.

Marguerite, it’s wonderful to speak with you today. Let me begin by saying what an honour this is. Your discovery of francium changed our understanding of the periodic table forever.

Well, that’s rather grand, isn’t it? When I was sifting through those uranium samples day after day, I hardly imagined I was “changing understanding forever.” I was simply a technician doing my job – though I must say, a job I found utterly fascinating.

But you were far more than just a technician, weren’t you? You became Marie Curie’s personal assistant, her préparateur.

Ah yes, but that title came with quite a story. When I walked into that dark house on the Rue Pierre-Curie for my interview in 1929, I was convinced I’d made a dreadful impression. The whole place seemed melancholy and sombre – nothing like the bustling laboratory I’d imagined. Marie Curie herself appeared rather stern during our meeting, and when she thanked me in that polite way people do when they’re dismissing you, I was certain that was that.

You can imagine my astonishment when Madame Galabert’s letter arrived a few days later, informing me that Madame Curie had decided to hire me. What I thought would be a brief position turned into twenty years at the Institut du Radium. Marie Curie saw something in me that I hadn’t even recognised in myself.

What was it like working so closely with such an iconic figure?

Marie Curie was… well, she was formidable. But also patient, particularly with someone like me who knew nothing about radioactivity. I’d been trained for simple chemical operations – kitchen recipes, really. She took the time to teach me herself, despite all her committees and travels.

There was this marvellous moment of mutual joy whenever we succeeded in preparing a radioactive product of exceptional purity. She’d light up in a way that reminded you why she’d devoted her life to this work. For someone who’d discovered radium and polonium, to still find such pleasure in a well-executed preparation – that taught me something profound about scientific curiosity.

After her death in 1934, you continued working with André-Louis Debierne on actinium research. Tell us about that period and how it led to your discovery.

Those were challenging years. Losing Marie Curie was devastating – not just personally, but scientifically. Debierne and I carried on, and I was promoted to radiochemist, which felt like an enormous responsibility.

I’d spent years purifying actinium from uranium ore – backbreaking work, really. You must understand, we’re talking about extracting perhaps 0.2 milligrams of actinium from an entire tonne of uranium ore. It required absolute precision and endless patience.

Then in 1935, I read this American paper claiming they’d detected beta particles from actinium. Something didn’t sit right with me. The energy levels they reported simply didn’t match what I knew about actinium’s behaviour. I thought to myself, “These Americans might be clever, but I’ve been working with this element for years.”

That scepticism led to one of the most important discoveries in nuclear physics. Can you walk us through the technical process?

Now this is where it gets interesting. I suspected that what the Americans were seeing wasn’t beta radiation from actinium itself, but from a daughter element – something actinium was decaying into.

I prepared the purest actinium samples I could manage and studied their radiation immediately after purification. The key was speed – I had to measure the radioactivity of freshly prepared actinium, then measure it again later. The initial activity was different from what we typically saw, but it quickly became the normal actinium signature.

This told me that some of the actinium was emitting alpha particles – losing two protons and two neutrons – which would transform element 89 into element 87. Element 87 had been predicted by Mendeleev as “eka-caesium,” but no one had actually found it.

How did you confirm this was indeed a new element?

Chemical behaviour, my dear fellow. If this truly was element 87, it should be an alkali metal with properties similar to caesium. I tested this by precipitating caesium as the perchlorate in the presence of my mystery element.

Sure enough, the new element co-precipitated with caesium, proving they had very similar chemical properties. That was the moment I knew – 7th January, 1939. I had found francium.

Why did you choose that name?

After France, naturally. As the discoverer, I had the privilege of naming it. France had given me everything – my education, my opportunity, my mentor. It seemed only fitting.

Yet your discovery wasn’t announced by you directly, was it?

No, that’s quite right. Jean Baptiste Perrin presented my note to the Académie des Sciences because I was merely a laboratory assistant without proper university credentials. Rather galling, when you think about it – discovering an element but not being deemed qualified to announce your own work.

That experience taught me something important about institutional barriers. Not having a bachelor’s degree shouldn’t have mattered a jot when the evidence was so clear, but institutions have their rules, don’t they?

This led you to pursue formal education later on.

Indeed. I received a grant to study at the Sorbonne, though they required me to complete the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree before I could pursue my doctorate. Rather like being asked to prove you can read before they’ll let you write a novel! I graduated with my Doctorate of Physics in 1946.

Let’s discuss francium’s properties and potential applications. What did you hope it might achieve?

This is where the story becomes rather bittersweet. I was tremendously excited about francium’s potential medical applications. My early research suggested it concentrated in tumours, and I hoped it might serve as a diagnostic tool for cancer.

The irony, of course, is almost unbearable. Here I was, hoping francium would help fight cancer, whilst it was simultaneously giving me the very disease I thought it might help diagnose.

That raises the difficult question of laboratory safety in your era.

Now that’s something I became quite passionate about in my later years. The safety practices when I started were appalling – criminally negligent, really. We worked without gloves, without proper shielding. Irène Joliot-Curie used mouth pipetting with radioactive solutions. Can you imagine?

The Radium Girls had won their landmark court case in 1928, just months before I started at the institute, yet we learned nothing from their suffering. Marie Curie carried test tubes of radium in her pockets. We thought dedication to science required accepting these risks.

By my later years, I became something of a walking radiation detector – the counters would go off when I entered laboratories. I made it my mission to warn students about the horrible consequences of radiation exposure. No scientific discovery is worth a human life.

How did your illness progress?

The bone cancer was… gruesome. It spread throughout my body, took my eyesight, pieces of my hands. I spent the last fifteen years of my life in treatment. But you know what? I never regretted the work itself, only that we didn’t understand how to do it safely.

Despite everything, you achieved remarkable recognition – the first woman elected to the Académie des Sciences.

March 12th, 1962. They called it a revolution. After all those years of women being excluded – Marie Curie herself was denied this honour – I became the one to break through.

The press had quite a field day with it. They loved the story of Marie Curie’s student achieving what her mentor never could. Though I must say, some of the newspaper accounts were dreadfully inaccurate about my life and work.

What was your relationship with institutional recognition more broadly?

I learned to use every tool at my disposal. Being a woman in science meant you had to be rather clever about circumventing obstacles. I’d apply directly to the Ministries of Education, Research, and Defence for laboratory funding, using my status as both a famous scientist and a woman to get around intermediaries.

At Strasbourg, where I headed the nuclear chemistry department from 1949, I insisted on maintaining proper dignity and scientific rigour. No liberties or casual first-name basis in the laboratory – we were serious scientists doing serious work. Though I did continue the afternoon tea tradition from the Institut du Radium. A bit of civilised relaxation never hurt anyone.

Looking back, what would you change about how dangerous research was conducted?

Everything about our safety protocols, obviously. But more fundamentally, I’d change the attitude that suffering for science was somehow noble or necessary. That’s complete nonsense.

We should have demanded proper shielding, rotation of personnel, regular medical monitoring. We should have recognised that protecting researchers was essential to protecting the research itself. Dead scientists can’t make discoveries.

Do you have any regrets about the practical applications of francium?

Francium turned out to be rather like discovering a beautiful butterfly that lives for only moments. Its longest-lived isotope has a half-life of just 22 minutes. At any given moment, there’s less than a gram of francium on the entire Earth.

So whilst I’d hoped for medical applications, francium’s extraordinary instability made that impractical. But you know, that doesn’t diminish its scientific importance. It completed our understanding of the naturally occurring elements. It taught us about radioactive decay. And modern researchers are using it to study fundamental physics in ways I never imagined.

What advice would you give to women entering nuclear science today?

First, don’t let anyone tell you that lacking formal credentials disqualifies you from making discoveries. I had no university degree when I found francium, yet the element existed regardless of what papers hung on my wall.

Second, insist on proper safety protocols. Don’t let anyone pressure you into taking unnecessary risks in the name of scientific dedication. That’s not dedication – that’s stupidity.

Third, be prepared to fight for recognition of your work. Institutions change slowly, and you may need to be quite persistent. But don’t let bitterness consume you. Channel that energy into doing better science.

Any final thoughts on your legacy?

I hope I’m remembered not just for discovering francium, but for proving that extraordinary science can come from unexpected places. I was a technician who became a world-class physicist through curiosity, hard work, and the guidance of an exceptional mentor.

I also hope my story serves as a warning. Scientific progress without adequate safety measures isn’t progress at all – it’s human sacrifice disguised as heroism. We must do better.

And perhaps most importantly, I hope young women see that barriers exist to be broken. Marie Curie couldn’t enter the Académie des Sciences, but her student could. Each generation should go further than the last. That’s how we honour our mentors – by surpassing them.

Thank you, Marguerite. Your story is indeed one of triumph over tremendous obstacles.

Triumph and tragedy, I’d say. But that’s often how the most important stories go, isn’t it? The key is ensuring the triumph outlasts the tragedy.

Letters and emails

Following our conversation with Marguerite Perey, we’ve been overwhelmed by the response from readers eager to explore her groundbreaking work and remarkable resilience in greater depth. We’ve selected five letters and emails from our growing community who want to ask her more about her life, her work, and what she might say to those walking in her footsteps – each bringing their own perspective from different corners of the world and various stages of their scientific journeys.

Brooklyn Hayes, 29, Science Communicator, Toronto, Canada:

Marguerite, I’m fascinated by your precision work with such tiny quantities of actinium – extracting 0.2 milligrams from a tonne of uranium ore sounds impossibly delicate. What specific purification techniques did you develop that weren’t in the textbooks? And do you think modern mass spectrometry would have changed your approach to isolating francium, or were your chemical separation methods actually more reliable for such unstable isotopes?

Brooklyn, what a delightfully precise question! You’ve touched on something quite dear to my heart – the art of working with what others would consider impossibly small quantities.

The purification techniques I developed were born from sheer necessity, really. When you’re working with such minute amounts of actinium, traditional gravimetric methods simply won’t do. I had to devise what I called “carrier-free” preparations, where I used the radioactive decay itself as my guide rather than relying on weighable quantities of material.

My approach involved repeated crystallisation using caesium and rubidium salts as carriers – not because I needed the bulk, but because the alkali metals would co-precipitate with any francium present whilst leaving behind the actinium parent. I’d dissolve and re-crystallise dozens of times, each cycle concentrating my mystery element further. The key was working quickly – francium’s 22-minute half-life meant every procedure had to be choreographed like a ballet.

What the textbooks never taught was the importance of listening to your samples. I could tell the purity of my preparations by the sound the Geiger counter made, the way the precipitates formed, even the colour changes during crystallisation. These weren’t documented techniques – they were hard-won intuitions from years of handling radioactive materials.

As for modern mass spectrometry, well, that’s quite fascinating to contemplate! Such precise atomic identification would certainly have accelerated the confirmation process enormously. But you raise an astute point about chemical methods being more reliable for unstable isotopes. Mass spectrometry requires the element to remain intact long enough for analysis, whereas my chemical approach worked precisely because it exploited francium’s natural behaviour as an alkali metal.

The chemical properties don’t lie, regardless of how fleeting the element might be. When francium co-precipitated with caesium perchlorate, it was announcing its identity through fundamental atomic structure, not just mass. I suspect that even with today’s sophisticated instruments, researchers working with extremely short-lived isotopes would benefit from returning to these classical separation techniques as confirmation methods.

The real advantage of chemical purification is that it teaches you to understand your element intimately – its preferences, its habits, its personality, if you will. No instrument can replace that kind of relationship between scientist and subject.

Rodrigo Mendes, 42, Physics Professor, São Paulo, Brazil:

If you could go back and redesign the scientific institutions of your time, what structural changes would you implement to better support women researchers while also maintaining rigorous safety standards? I’m thinking about how we balance mentorship, formal credentials, and practical expertise – especially for brilliant minds who don’t fit traditional academic pathways.

Rodrigo, what a profound question you’ve posed. If I could redesign the institutions of my era… goodness, where would one even begin?

First and foremost, I’d establish what I might call “competence committees” rather than credential committees. Too many brilliant minds were dismissed simply for lacking the proper university stamps. When I discovered francium, the evidence spoke for itself – yet because I was merely a laboratory technician, Jean Baptiste Perrin had to present my findings to the Académie. Absurd! Scientific truth doesn’t require a bachelor’s degree to validate it.

I’d institute mandatory mentorship programmes, but with proper structure. Marie Curie was an exceptional mentor, but the system relied entirely on individual goodwill. What if she hadn’t taken an interest in me? There were undoubtedly other young women with potential who simply never encountered the right guidance. Every senior researcher should be required to nurture promising assistants, regardless of their formal education.

Most crucially, I’d establish rigorous safety protocols with teeth behind them. No more of this romantic nonsense about suffering for science! Regular medical examinations, mandatory rotation away from radioactive materials, proper shielding equipment – and severe penalties for institutions that failed to provide them. The Radium Girls had already won their court case in 1928, yet we learned nothing from their tragedy.

For women specifically, I’d create alternative pathways to recognition. Perhaps “practical doctorates” based on demonstrated research achievements rather than coursework. I earned my credentials eventually, but how many talented women never got that chance? We needed flexible systems that acknowledged different routes to expertise.

I’d also mandate mixed-gender committees for all scientific appointments and recognitions. The old boys’ network was simply too entrenched. When the Académie des Sciences finally elected me in 1962, they called it revolutionary – but it shouldn’t have been! Women had been doing excellent science for decades.

Most importantly, I’d establish what we might call “scientific socialism” – proper funding for laboratory assistants, technicians, and support staff. Science isn’t just about the famous names at the top. Every discovery rests on a foundation of careful, often anonymous work by people like I was in 1929.

The goal isn’t to lower standards – quite the opposite. It’s to ensure that excellence can emerge from anywhere, be properly nurtured, and receive the recognition it deserves, whilst keeping everyone alive in the process!

Rather ambitious, I suppose, but then again, discovering new elements requires a bit of ambition, doesn’t it?

Nura Khan, 35, Nuclear Engineer, Mumbai, India:

You mentioned that francium concentrated in tumours, which gave you hope for cancer diagnosis. Given that we now use targeted radioisotopes like lutetium-177 and actinium-225 in cancer therapy, do you think there might still be untapped medical potential in francium’s isotopes? What would you advise modern researchers who are trying to harness extremely short-lived radioactive elements for therapeutic applications?

Nura, how thrilling that you’re working in nuclear engineering! Your question touches on something that has haunted me for decades – the unrealised medical potential of francium.

You see, my early observations of francium’s behaviour in biological systems were quite promising. It appeared to concentrate preferentially in certain tissues, particularly tumorous ones, which suggested it might serve as what we now call a “tracer.” I envisioned using tiny amounts to illuminate cancer cells, making them visible to physicians before the disease advanced too far.

The cruel irony, of course, is that francium’s very properties that made it medically interesting – its intense radioactivity and tissue affinity – also made it lethally dangerous. But your mention of modern therapeutic isotopes gives me considerable hope! If researchers have successfully harnessed actinium-225, which is certainly no gentle lamb, then perhaps francium’s isotopes deserve another look.

The key insight from my era was understanding that extremely radioactive elements could be both poison and cure, depending on dosage and targeting. What we lacked were the sophisticated delivery mechanisms and precise dosimetry that modern medicine has developed. Francium-223, for instance, has a 22-minute half-life – seemingly too brief for practical use. But perhaps that’s precisely its advantage! Such rapid decay might allow for intense, localised treatment followed by swift elimination from the body.

My advice to researchers pursuing short-lived isotopes would be this: don’t dismiss an element simply because it appears inconveniently ephemeral. Nature often provides exactly what we need, but not always in the form we expect. Francium taught me that some of the most powerful tools are also the most fleeting.

I’d encourage them to investigate francium’s daughter products as well. The decay chain might offer a spectrum of therapeutic options – perhaps the francium itself serves as a delivery mechanism that transforms into more stable, therapeutically active isotopes once positioned correctly.

Most importantly, learn from my generation’s mistakes regarding safety! These powerful isotopes demand respect and proper handling. The potential benefits are extraordinary, but never at the cost of the researchers’ lives. Proper shielding, remote handling equipment, and rigorous exposure monitoring must be non-negotiable.

The dream I had in the 1940s – using radioactive elements to fight cancer rather than cause it – remains within reach. Modern technology has simply made it safer to pursue. That gives me tremendous satisfaction, knowing that perhaps francium might still fulfill its healing destiny, even if I couldn’t witness it myself.

Markus Lindberg, 38, Science Policy Analyst, Stockholm, Sweden:

Here’s a hypothetical that keeps me awake at night: imagine if modern radiation safety protocols had existed in 1929 when you started at the Institut du Radium. With proper shielding and exposure limits, you might have lived decades longer – what discoveries do you think you could have made with those extra years? Would francium research have advanced differently, or would you have turned your attention to entirely new elements or applications?

Markus, what a haunting thought you’ve presented! Those extra decades… You know, I’ve pondered this myself during my long years of illness.

With proper radiation protection from 1929 onwards, I might have lived until the 1990s – perhaps even longer. The scientific landscape would have been entirely different, wouldn’t it? I could have witnessed the development of particle accelerators, the discovery of transuranium elements, even the early days of what you call nuclear medicine.

But here’s what truly excites me about your hypothetical: I believe francium research would have advanced in ways we can barely imagine. You see, my work was tragically curtailed just as I was beginning to understand francium’s potential. With decades more, I could have explored its isotopes thoroughly, perhaps discovering longer-lived varieties that might have proven medically useful.

I suspect I would have turned my attention to the gap between francium and the actinides – that mysterious region of the periodic table that remained largely unexplored in my lifetime. With better equipment and safer conditions, who knows what elements might have been found? Perhaps I could have contributed to understanding nuclear structure in ways that would have accelerated the entire field.

More intriguingly, I think I would have become quite the advocate for what you might call “responsible nuclear research.” Having experienced the consequences of cavalier attitudes toward radiation, I could have been a powerful voice for safety protocols decades before they were finally implemented. Perhaps fewer researchers would have suffered the fate that befell me, Irène Joliot-Curie, and so many others.

I also suspect I would have established a proper school for radiochemistry – not just teaching techniques, but emphasising the ethical responsibilities that come with handling such dangerous materials. The younger generation needed guidance not just in method, but in wisdom.

But you know, Markus, there’s something almost poetic about the timing of my death in 1975. I lived just long enough to see my field mature, to witness the first successful medical applications of radioactive isotopes, and to know that my discovery of francium had found its place in the grand scheme of nuclear physics.

Those extra years would have been marvellous, certainly. But perhaps what matters most is that the work continued, that others built upon what I began, and that the lessons learned from my suffering helped make science safer for future generations.

Sometimes the most important contribution isn’t what you discover, but what you teach others to avoid.

Selam Tesfaye, 26, Medical Physics Student, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia:

Your relationship with Marie Curie seems so pivotal to your development as a scientist. I’m curious about the quieter moments – did she ever share doubts about her own work, or express concerns about the health risks you were all taking? How did those private conversations shape your understanding of what it truly means to be a pioneering scientist, especially as a woman breaking barriers?

Oh Selam, what a tender question you’ve asked. Those private moments with Marie Curie… they revealed so much more than her public persona ever showed.

I remember one particular afternoon in 1932 – she’d returned from yet another committee meeting, looking absolutely drained. The constant travel, the endless requests for her expertise, the political pressures… it was wearing her down terribly. She sat at her desk, removed those thick spectacles she’d begun wearing, and rubbed her eyes with such weariness.

“Marguerite,” she said quietly, “sometimes I wonder if we’ve opened Pandora’s box with these radioactive elements.” This from the woman who’d devoted her entire life to their study! She was watching her own health decline, seeing the cataracts forming in her eyes, feeling the fatigue that never quite lifted. Yet she couldn’t bring herself to step away from the work.

What struck me most was her fierce protectiveness over our research, but also her growing anxiety about its implications. She’d mention the medical possibilities with genuine excitement – radium therapy was showing promise for cancer treatment – but then fall silent, perhaps thinking of her own deteriorating condition.

She never directly warned me about the health risks – I think she couldn’t bear to discourage my enthusiasm. But I began noticing how she’d subtly encourage me to vary my duties, to spend time on theoretical calculations rather than hands-on laboratory work. She’d suggest I attend lectures at the Sorbonne, ostensibly for my education, but I suspect she was trying to limit my exposure.

The most profound conversation we had was just months before her death. She spoke about legacy – not the scientific discoveries, but the responsibility we bore as women in science. “Every door we open,” she said, “makes it easier for the next woman to enter. But we must also ensure she enters safely.”

That comment shaped everything I did afterward. When I discovered francium, I wasn’t just representing myself – I was carrying forward Marie Curie’s hopes for women in science. When I later fought for proper safety protocols, I was honouring her unspoken concerns about the price we were paying for knowledge.

She taught me that being a pioneering scientist, particularly as a woman, meant accepting a dual burden: advancing human understanding whilst ensuring that progress doesn’t consume the very people creating it. The quieter moments revealed her humanity – her doubts, her fears, her deep sense of responsibility for those who would follow in our footsteps.

That’s the real legacy she left me, Selam – not just scientific methodology, but moral courage.

Reflection

Marguerite Perey died on 13th May 1975 at the age of 65, her body finally succumbing to the radiation-induced bone cancer that had ravaged her for fifteen years. Her death marked the end of a life defined by extraordinary scientific achievement shadowed by tragic irony – the woman who discovered francium, hoping it might diagnose cancer, ultimately died from the very disease she’d sought to combat.

Throughout our conversation, Perey’s perspective often differed markedly from sanitised historical accounts. Where official records emphasise her mentorship under Marie Curie, she revealed the private doubts and growing anxieties her famous mentor harboured about their dangerous work. Her candid admission that institutional barriers forced Jean Perrin to announce her discovery contradicts narratives that downplay the gender discrimination she faced. Most strikingly, she corrected the record about safety awareness – insisting that by the 1940s, researchers knew the risks but chose to ignore them, challenging myths about innocent scientific martyrdom.

Historical gaps remain significant. Details about her specific purification techniques exist largely in her personal laboratory notebooks, housed at the University of Strasbourg archives. The extent of her radiation exposure remains contested, with some accounts suggesting her symptoms were initially misdiagnosed as chemical burns rather than radiation damage. Contemporary scientists continue building on Perey’s legacy in ways she never imagined. Modern researchers use francium in quantum physics experiments and fundamental particle research. The element she discovered now serves as a testing ground for theories about CP violation and atomic structure, whilst improved safety protocols directly reflect lessons learned from her suffering.

Perhaps most powerfully, Perey’s story resounds with today’s ongoing battles for laboratory safety, gender equality in nuclear science, and the ethical responsibilities we bear when pursuing dangerous research. Her fierce advocacy for protective equipment and exposure monitoring helped establish standards that protect countless contemporary researchers. She blazed a trail not just through scientific discovery, but through institutional reform – proving that true pioneers must sometimes sacrifice themselves to light the way for others.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview represents a dramatised reconstruction based on extensive historical research, including Marguerite Perey‘s published papers, archived correspondence, biographical accounts, and documented statements. While grounded in factual evidence about her life, work, and era, the conversational format and specific dialogue are imaginative interpretations designed to illuminate her scientific contributions and personal experiences. Readers should understand this as a creative exploration of historical themes rather than verbatim testimony, intended to honour Perey’s legacy whilst making her remarkable story accessible to contemporary audiences.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved. | 🌐 Translate

Leave a comment