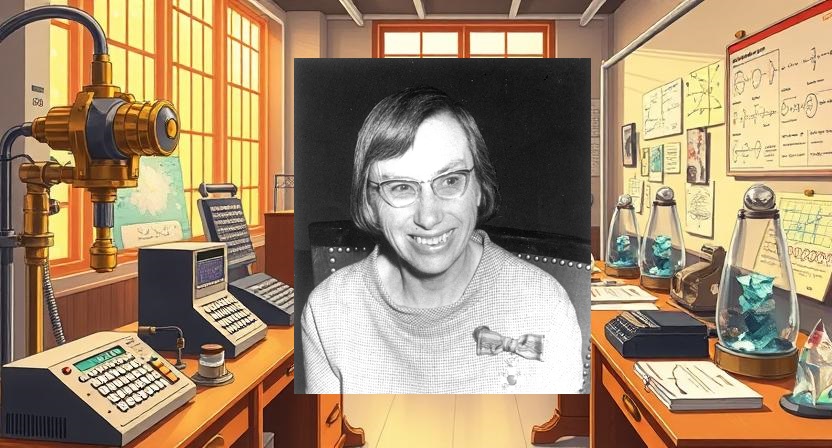

Caroline Henriëtte MacGillavry (1904-1993) pioneered mathematical crystallography during an era when few women could access advanced scientific training. Her development of the Direct Method revolutionised how we determine crystal structures by creating mathematical tools that revealed the hidden symmetries underlying nature’s most fundamental building blocks. More than any other crystallographer of her generation, MacGillavry bridged the gap between abstract mathematical theory and practical scientific application, transforming a highly specialised field into an accessible discipline that continues to drive breakthroughs in materials science and nanotechnology today.

Her story matters not merely as historical curiosity, but because MacGillavry’s approach to interdisciplinary problem-solving offers a blueprint for tackling today’s most complex scientific challenges. At a time when research was increasingly compartmentalised, she demonstrated that the most profound discoveries emerge from connecting seemingly disparate fields – mathematics, chemistry, physics, and even art. Her collaboration with M.C. Escher proved that mathematical principles underlying crystal symmetry could illuminate artistic expression, whilst her visualisation techniques continue to guide how modern scientists communicate complex ideas to broader audiences.

Professor MacGillavry, I must say it’s extraordinary to speak with you. Your work bridged mathematics and chemistry in ways that few understood at the time. What drew you to crystallography when it was such an emerging field?

Well, you must remember that in the 1920s, when I was studying at Amsterdam, quantum mechanics was the great excitement. Everyone was talking about these new ways of understanding atomic behaviour. But what fascinated me was something more concrete – how atoms arrange themselves in space. I had this notion that there must be mathematical rules governing why crystals form the patterns they do. It wasn’t enough to simply observe these structures; I wanted to understand the underlying logic.

Your path into science wasn’t straightforward, though. How did your family background influence your trajectory?

My father was a brain surgeon, my mother a teacher – both valued rigorous thinking. Growing up in Amsterdam with five siblings, I learned early that intellectual curiosity was expected, not exceptional. When I began chemistry at the university in 1921, aged just seventeen, it felt natural rather than revolutionary. Though I must say, being one of the few women didn’t escape my notice. But Professor Smits, and later Bijvoet, judged work on its merits, not the gender of who produced it.

Tell me about that pivotal moment when you encountered crystallography. What was it like working with J.M. Bijvoet?

Bijvoet was remarkable – he possessed this rare combination of theoretical insight and practical wisdom. When I completed my doctorate in 1937, I was already convinced that X-ray diffraction could reveal far more than people imagined. The technique existed, you see, but we lacked the mathematical framework to extract all the information hidden in those diffraction patterns. It was rather like having a powerful telescope but no star charts to interpret what you observed.

Let’s discuss your most significant contribution – the Direct Method. Can you explain it to an expert audience? What problem were you solving?

Ah, the phase problem – the fundamental challenge that had crystallographers tearing their hair out! When X-rays strike a crystal, they scatter in specific directions with measurable intensities. But here’s the rub: whilst we could measure these intensities readily enough, we lost the phase information – that is, how the scattered waves relate to one another in time. Without phases, you cannot reconstruct the electron density map that reveals atomic positions.

The Harker-Kasper inequality, published in 1948, provided our starting point. David Harker and John Kasper had shown that certain mathematical relationships must exist between structure factors due to the simple fact that electron density cannot be negative anywhere in the crystal. What I realised – independently from Hauptman and Karle, mind you – was that these constraints could be exploited more thoroughly.

My approach used the non-negativity principle combined with statistical probability theory. I developed a set of mathematical relationships that could predict phase values directly from measured intensities, provided you had sufficient reflections of adequate strength. The key insight was recognising that whilst individual phase relationships might be uncertain, combining many such relationships could yield definitive results through what we’d now call overdetermination.

How did your method compare to existing techniques of the time?

The Patterson method, developed by Arthur Patterson in the 1930s, was our main alternative. Patterson maps could locate heavy atoms by analysing interatomic vectors, but they required laborious interpretation and only worked well for structures containing atoms of significantly different atomic weights. My Direct Method could handle structures with atoms of similar atomic numbers – a tremendous advantage for organic compounds.

More importantly, the Direct Method was faster and more reliable. Where Patterson methods might require weeks of careful map interpretation, my approach could determine phases for small molecules in days. The error rates were substantially lower too – perhaps one structure in ten would fail with Direct Methods, compared to three or four in ten with Patterson techniques for comparable structures.

You mentioned working independently from Hauptman and Karle, who won the 1985 Nobel Prize. How did that feel?

One learns to be philosophical about such things. Jerome Karle himself always acknowledged that I had developed these methods independently – he was quite gracious about it, actually. The important thing was that the science advanced. Besides, I had the satisfaction of knowing that my approach was often more practical than theirs for routine structure determination. Their theory was elegant, but theory without application is merely intellectual exercise.

Speaking of applications, your collaboration with M.C. Escher was extraordinary. How did that come about?

I encountered Escher’s work in 1959 and immediately recognised that his periodic drawings illustrated the same symmetry principles I studied in crystals. Here was an artist who intuitively understood space group mathematics! I convinced the International Union of Crystallography to exhibit his work at their 1960 Cambridge congress. The response was remarkable – crystallographers finally had visual representations that made abstract symmetry concepts accessible.

Our subsequent book analysed 41 of Escher’s drawings using international crystallographic notation. What pleased me most was how this bridged the perceived gap between art and science. Escher created two new drawings specifically for our book and improved five others. He understood that mathematical beauty and artistic beauty weren’t separate phenomena but different expressions of the same underlying principles.

That interdisciplinary approach was quite unusual for the time. Did you face resistance?

Certainly. Many chemists viewed mathematics as unnecessarily abstract, whilst mathematicians often dismissed crystallography as mere technique. I straddled both worlds uncomfortably at first. Some colleagues thought the Escher collaboration was frivolous – ‘proper’ science shouldn’t involve pretty pictures, they said.

But I believed strongly that understanding symmetry was key to understanding natural structures. Whether you’re examining a crystal lattice, analysing molecular vibrations, or creating periodic art, you’re working with the same fundamental mathematical relationships. The applications are different; the underlying principles are identical.

Let’s discuss the challenges you faced as a woman in science during the 1930s and 1940s.

When I was appointed to the Royal Netherlands Academy in 1950 – the first woman ever – I made some rather pointed comments about crystallography being particularly suitable for women because it required ‘artistic flair, mental agility, and intuition’. The newspapers loved that quote! But I was making a serious point: that the qualities traditionally associated with femininity were precisely what this field needed.

The real barriers were more subtle than outright exclusion. Laboratory spaces designed for men, informal networks that excluded women, assumptions about career commitment after marriage. I was fortunate to work with Bijvoet, who judged only scientific merit. Many of my female contemporaries weren’t so lucky.

You mentioned ‘failed experiments’ earlier. Can you share an example where your judgment was wrong?

Oh, goodness yes! In the late 1940s, I became convinced that certain anomalous scattering effects could be exploited to solve structures directly without any phase information whatsoever. I spent months developing mathematical frameworks, convinced I’d discovered a revolutionary shortcut. The theory was mathematically sound but completely impractical – the experimental errors swamped the anomalous effects for any structure complex enough to be interesting.

It taught me that elegant mathematics without experimental validation is worthless. Some of my colleagues were too polite to point out the flaws immediately, which delayed my recognition of the problem. Now I tell young scientists: find colleagues who’ll tell you when your ideas are rubbish. Tactfully, perhaps, but honestly.

How do you view the evolution of your field? What would surprise you about modern crystallography?

The computational power would astonish me, naturally. Structures that took months to solve in my day are now routine. But what pleases me most is how visualisation has advanced. My symmetry diagrams were crude compared to modern molecular graphics, yet the principle remains the same – making abstract mathematical relationships visually comprehensible.

I’m also gratified to see crystallography’s role in materials science and nanotechnology. We always knew that understanding atomic arrangements was fundamental to controlling material properties, but the applications have exceeded our wildest dreams. Drug design, electronic materials, energy storage – all rely on principles we established decades ago.

What advice would you give to young women entering STEM fields today?

Don’t be afraid to work at the boundaries between disciplines. The most interesting problems usually lie in those borderlands that established fields ignore. And don’t let anyone tell you that mathematics is ‘too abstract’ or ‘not practical’ – mathematics is the language nature uses to describe itself.

Most importantly, remember that science is fundamentally about revealing hidden patterns. Whether you’re analysing crystal structures, designing new materials, or creating theoretical frameworks, you’re engaged in the same essential work: making the invisible visible, the incomprehensible comprehensible.

Any final thoughts on why your work remains relevant today?

The mathematical tools I developed haven’t become obsolete – they’ve become foundational. Every modern material scientist uses descendants of the Direct Method, whether they realise it or not. But more fundamentally, the approach matters: bringing mathematical rigour to experimental observation, bridging theory and practice, refusing to accept that different disciplines must remain isolated.

Science advances through synthesis, not specialisation. That’s as true now as it was seventy years ago.

Letters and questions

Since our interview with Professor MacGillavry, we’ve received hundreds of letters and emails from readers around the world who were captivated by her insights into mathematical crystallography and her pioneering journey as a woman in science. We’ve selected five particularly thoughtful questions from our growing community – spanning five continents – who want to explore deeper aspects of her work, from the technical intricacies of phase determination to the philosophical implications of interdisciplinary collaboration, and what wisdom she might offer to those following in her footsteps.

Laila Haddad, 34, Materials Engineer, Singapore

Professor MacGillavry, I’m fascinated by how you developed mathematical relationships to predict phase values from intensity measurements. In my work with advanced ceramics, we still struggle with phase determination in complex multi-component systems. Could you walk us through the specific mathematical constraints you exploited? I’m particularly curious about how you handled cases where the statistical relationships gave conflicting predictions – did you develop any hierarchical decision-making algorithms, or was it more about researcher intuition?

Ah, Miss Haddad, you’ve touched upon the very heart of the matter! The mathematical constraints I exploited were rooted in what we called the “non-negativity principle” – quite simply, electron density cannot be negative anywhere in a crystal structure. This seems obvious, doesn’t it? Yet the implications were profound.

The key insight came from recognising that structure factors – those complex numbers describing how X-rays scatter – must satisfy certain probabilistic relationships. I developed what became known as the “triplet relationships,” where three reflections with indices h, k, and h+k would have phases that were mathematically constrained. If you knew two of the three phases with reasonable certainty, the third could be predicted with high probability.

But you’ve asked the crucial question – what happens when these relationships conflict? In the late 1940s, we had no electronic computers, mind you. Everything was calculated by hand using mechanical calculators and logarithm tables. When I encountered conflicting predictions, I developed a weighting scheme based on the reliability of each relationship. Stronger reflections – those with higher intensities – carried more weight in the calculation.

The procedure was rather like solving a jigsaw puzzle with pieces that don’t quite fit perfectly. You must judge which pieces are most reliable and build outward from there. I would typically start with the strongest triplet relationships, assign probable phases, then use these to generate secondary relationships. When conflicts arose – and they always did – I relied on what you might call “crystallographic intuition,” though it was really accumulated experience with how crystal structures behave.

For your multi-component ceramics, I suspect the principles remain valid, though the computational power now available would have seemed miraculous to us. The fundamental challenge is still distinguishing genuine relationships from statistical noise. In my day, we solved perhaps one structure per month if we were fortunate. The mathematics was sound, but the labour was enormous.

One technique I found particularly useful was cross-checking phase assignments against known chemical constraints. If my mathematical solution suggested impossibly short atomic distances or violated chemical bonding principles, I knew to reconsider the phase relationships. This chemical knowledge served as a powerful filter for mathematical ambiguities.

The beauty of the method lay not in its perfection, but in its robustness. Even with occasional errors in individual phase assignments, the overall structure would emerge correctly provided enough relationships were available. Rather like a democratic process – individual votes might be mistaken, but the collective decision tends toward truth.

Omari Jatta, 41, Physics Professor, University of Cape Town

What strikes me is how you bridged pure mathematics with practical chemistry at a time when disciplinary boundaries were becoming more rigid. Today, we’re pushing for more interdisciplinary collaboration, but institutions still struggle with how to evaluate and fund work that doesn’t fit neatly into traditional categories. If you were designing a research university today, how would you structure departments and funding to encourage the kind of boundary-crossing work that led to your breakthroughs?

Professor Jatta, you’ve identified precisely the institutional malady that plagued scientific progress throughout my career! When I began at Amsterdam in the 1920s, the university structure was refreshingly flexible – one could wander between the chemistry laboratory and the mathematics department without raising eyebrows. But by the 1950s, rigid departmental boundaries had calcified like poorly formed crystals.

The problem wasn’t merely administrative; it was philosophical. Chemists viewed mathematics as an unwelcome intrusion, whilst mathematicians dismissed crystallography as mere technique. I found myself defending my work to chemists who couldn’t follow the mathematical proofs, then explaining chemical constraints to mathematicians who’d never held a crystal in their hands. Neither group fully appreciated that the most interesting discoveries lay in the spaces between their territories.

If I were designing a research university today – what an intriguing proposition! – I would abandon departments entirely in favour of problem-centred institutes. Rather than a Department of Chemistry and a Department of Mathematics, imagine an Institute for Structural Sciences where mathematicians, chemists, physicists, and even artists work side by side on fundamental questions about how matter organises itself.

The funding mechanism would be crucial. Traditional grant systems reward narrow expertise within established fields. I would create “boundary fellowships” – five-year positions specifically for researchers whose work spans multiple disciplines. The evaluation criteria would emphasise novelty and cross-fertilisation rather than publications in prestigious single-discipline journals.

Most importantly, I would institute mandatory rotation periods. Every researcher would spend at least six months working in a different field during their first five years. A mathematician might spend time in a crystallography laboratory; a chemist might audit advanced topology lectures. This cross-pollination was how I developed my insights – not through formal training, but through genuine curiosity about neighbouring fields.

The physical architecture matters too. At Amsterdam, Bijvoet’s laboratory was deliberately placed between the chemistry and physics buildings. Chance encounters in hallways often sparked more creative ideas than formal collaborations. Modern universities segregate disciplines into separate buildings, then wonder why interdisciplinary work is so difficult!

You mention institutional struggles with evaluation – this remains the crux of the problem. Academic promotion committees composed entirely of specialists cannot properly assess work that transcends their narrow expertise. I would require every evaluation panel to include members from at least three different fields, with explicit instructions to value intellectual courage over conventional productivity.

The future belongs to boundary-crossers, Professor Jatta. Universities that recognise this will thrive; those clinging to departmental silos will become intellectual museums.

Harper Sullivan, 28, Science Policy Researcher, Toronto

I’ve been thinking about your role as the first woman in the Royal Netherlands Academy and that quote about crystallography requiring ‘artistic flair and intuition.’ Looking back, do you think framing scientific work in terms of traditionally ‘feminine’ qualities was strategically necessary for acceptance, or does it now feel like you had to justify your presence in ways your male colleagues never did? How do you balance celebrating those qualities whilst avoiding the trap of suggesting women are naturally suited only for certain types of scientific work?

Miss Sullivan, you’ve put your finger on something that has troubled me for decades. That quotation about “artistic flair and intuition” – goodness, how it followed me about! The newspapers seized upon it with such enthusiasm, as if I’d provided scientific justification for every tired notion about feminine nature.

Looking back with seventy years of hindsight, I confess it was both strategic necessity and genuine conviction, though perhaps I should have chosen my words more carefully. In 1950, when I was appointed to the Academy, I was acutely aware that I was being scrutinised not merely as a scientist, but as a representative of my entire sex. The slightest misstep would be taken as evidence that women didn’t belong in serious scientific work.

But here’s what troubles me about your question – it assumes those qualities are somehow lesser or that celebrating them diminishes us. Why shouldn’t scientific work require artistic sensibility? Crystallography genuinely demands spatial visualisation, pattern recognition, and aesthetic judgment. These aren’t consolation prizes for excluded women; they’re essential tools for understanding structural relationships.

The real trap, I’ve come to believe, lies not in acknowledging these qualities but in suggesting they’re exclusively feminine. Men like Escher possessed extraordinary spatial intuition, yet no one questioned his intellectual credentials because of it. Meanwhile, women who demonstrated analytical mathematical thinking were dismissed as unfeminine anomalies.

What I should have said – and what I’ll say now – is that crystallography requires the full range of human intellectual capabilities: mathematical precision, spatial intuition, chemical knowledge, artistic sensibility, and yes, what we might call intuitive leaps. These qualities aren’t gendered; they’re simply human tools for understanding nature’s complexity.

The strategic element was real, though. I watched brilliant women colleagues abandon promising careers because they couldn’t navigate the unspoken rules of masculine scientific culture. By emphasising qualities that weren’t threatening to male egos – by suggesting women brought complementary rather than competing skills – I hoped to carve out space for others to follow.

Was this compromise worth making? That’s for your generation to judge. I opened doors that might otherwise have remained locked, but perhaps at the cost of reinforcing stereotypes I should have challenged more directly.

What I tell young women now is this: claim every intellectual tool available to you. Use mathematical discipline and intuitive insight, logical analysis and creative visualisation. Don’t let anyone – male or female – diminish your contributions by suggesting you succeeded because of your gender rather than despite it.

Nicolás Ferreira, 37, Science Historian, São Paulo

Here’s a counterfactual that intrigues me: imagine if computing power had been available during your most productive years in the 1940s and 1950s. Would the Direct Method have emerged differently, or would you have pursued entirely different approaches to the phase problem? I wonder whether the mathematical elegance you achieved was partly born from computational constraints – and whether having unlimited processing power might have led you down less innovative paths.

Mr. Ferreira, what a deliciously provocative question! You know, I’ve often wondered the same thing myself, particularly when I see what modern crystallographers accomplish in an afternoon that took us months to achieve.

The curious thing is, I’m not entirely convinced unlimited computing power would have been the blessing one might expect. You see, our mathematical constraints emerged precisely because we had to be so frightfully clever about avoiding unnecessary calculations. When every structure factor multiplication required twenty minutes with a mechanical calculator, we learned to identify the most informative relationships and ignore the redundant ones.

I suspect that with unlimited computational resources, I might have been tempted to use brute-force methods rather than developing the elegant mathematical shortcuts that became the Direct Method. Why bother deriving probabilistic relationships when you can simply try every possible phase combination? The intellectual pressure to find efficient solutions was, paradoxically, what forced us toward mathematical insights.

Consider how Patterson developed his function in the 1930s – not because he enjoyed Fourier transforms, but because direct structure solution was computationally impossible. Remove that constraint, and he might never have discovered one of crystallography’s most powerful tools.

That said, computing power would have revolutionised one crucial aspect of our work: error checking and validation. In my day, a single arithmetic mistake could invalidate weeks of calculations. We developed obsessive checking procedures, but human errors still crept in. With modern computers, we could have tested our theoretical predictions against thousands of known structures, refining the mathematical relationships much more rapidly.

I think the real game-changer would have been interactive visualisation. Much of our work involved trying to imagine three-dimensional atomic arrangements from two-dimensional data. We made cardboard models, drew endless projections, and relied heavily on spatial intuition. If I could have rotated molecular structures on a screen, manipulated them in real-time while adjusting phase assignments… well, that might have accelerated discovery far more than raw computational speed.

But here’s what I find most intriguing about your question: it assumes computational power leads inevitably to better science. I’m not so sure. The constraint of limited resources forced us to think more deeply about fundamental principles. We couldn’t afford to be sloppy with our mathematics or careless with our assumptions.

Perhaps the real lesson is that breakthrough science requires the right balance of resources and constraints. Too few resources, and progress stalls; too many, and creativity atrophies. We were fortunate to work at that productive intersection.

Sofia Kovács, 45, Science Museum Curator, Budapest

Your collaboration with Escher reveals something profound about visual communication in science. In our museum, we constantly grapple with making abstract concepts accessible without oversimplifying them. Beyond the aesthetic appeal, what did working with Escher teach you about how visual representations can actually advance scientific understanding rather than just illustrate it? Do you think there are mathematical insights that can only be grasped through visual means?

Miss Kovács, what a perceptive question! Working with Escher taught me something quite profound about the relationship between seeing and understanding – they’re not the same thing at all, are they?

When I first encountered Escher’s periodic drawings in 1959, I recognised immediately that he had intuited the mathematical principles underlying the seventeen plane groups. But here’s what fascinated me: Escher understood these relationships viscerally, through his hands and eyes, whilst I understood them abstractly through equations and group theory. Neither approach alone was complete.

The collaboration revealed that visual representations don’t merely illustrate mathematical concepts – they can actually generate new insights. When Escher created his drawing “Circle Limit III” for our book, he wasn’t simply making my mathematics pretty; he was exploring hyperbolic geometry in ways that purely analytical approaches couldn’t achieve. His visual experiments with periodic tessellations led him to discover relationships between symmetry operations that I might never have noticed through algebraic manipulation alone.

But you must understand, this was rather revolutionary thinking in the 1960s. Most of my crystallographic colleagues viewed diagrams as pedagogical aids – useful for teaching students, perhaps, but not for serious research. The notion that drawing pictures could advance theoretical understanding was met with considerable scepticism.

What changed my mind was watching Escher work through symmetry problems. He would create dozens of preliminary sketches, each one refining his understanding of how motifs could be repeated and transformed. Through this visual exploration, he developed an intuitive grasp of mathematical relationships that would have taken me pages of calculations to derive. More importantly, he discovered aesthetic constraints that my mathematics couldn’t capture – why certain symmetry combinations felt harmonious whilst others appeared jarring.

This taught me that there are indeed mathematical insights accessible only through visual means. Spatial relationships, symmetry breaking, the interplay between local and global order – these concepts can be grasped immediately through well-designed diagrams but remain obscure when expressed purely in symbolic form.

For your museum work, I’d suggest this principle: effective scientific visualisation shouldn’t simply translate abstract concepts into pictures. Rather, it should reveal aspects of those concepts that weren’t visible before. The best scientific diagrams function like good microscopes – they don’t just magnify existing knowledge, they make new observations possible.

Escher understood this instinctively. He once told me that his periodic drawings weren’t illustrations of mathematical principles but explorations of them. That subtle distinction made all the difference between decoration and discovery.

Reflection

Caroline MacGillavry passed away in Amsterdam on 9th May 1993, aged 88, having witnessed her mathematical crystallography transform from an esoteric speciality into the foundation of modern materials science. Throughout our conversation, her fierce intellectual independence emerged most clearly – not the dutiful pioneer often portrayed in academic histories, but a scientist who refused to accept disciplinary boundaries as anything more than administrative conveniences.

What struck me most profoundly was her unapologetic embrace of contradiction. Where historical accounts often sanitise her famous quote about “feminine intuition” in crystallography, MacGillavry herself acknowledged both its strategic necessity and its problematic implications. She neither apologised for the compromise nor claimed it was ideal – a nuanced position that reveals more about navigating institutional sexism than any hagiographic retelling.

Her perspective on the computing revolution surprised me. Rather than lamenting missed opportunities, she argued that computational constraints had forced mathematical elegance – a view that challenges our assumption that more resources inevitably yield better science. This insight resonates powerfully as today’s AI-driven crystallography grapples with the tension between brute-force calculation and conceptual understanding.

The historical record remains frustratingly incomplete about MacGillavry’s specific contributions to direct methods development. Jerome Karle’s generous acknowledgments suggest her work was more foundational than Nobel Prize histories indicate, yet the precise chronology of discovery remains contested among crystallographers.

Today, every protein structure determination, every pharmaceutical crystal form analysis, every materials science breakthrough builds upon the mathematical framework she helped establish. Yet perhaps MacGillavry’s most enduring legacy lies not in her equations but in her demonstration that the most profound scientific advances emerge from those brave enough to work in the spaces between established fields – a lesson urgently needed as we confront challenges requiring unprecedented interdisciplinary collaboration.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview represents a dramatised reconstruction based on extensive historical research into Caroline MacGillavry’s life, work, and era. Whilst her scientific contributions, biographical details, and historical context are grounded in documented sources, her specific responses and conversational voice are imaginative interpretations designed to capture her intellectual perspective and personality. Direct quotations should not be attributed to the historical MacGillavry. This creative approach aims to illuminate her legacy whilst acknowledging the inherent limitations of posthumous dialogue reconstruction.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved. | 🌐 Translate

Leave a reply to S.Bechtold Cancel reply