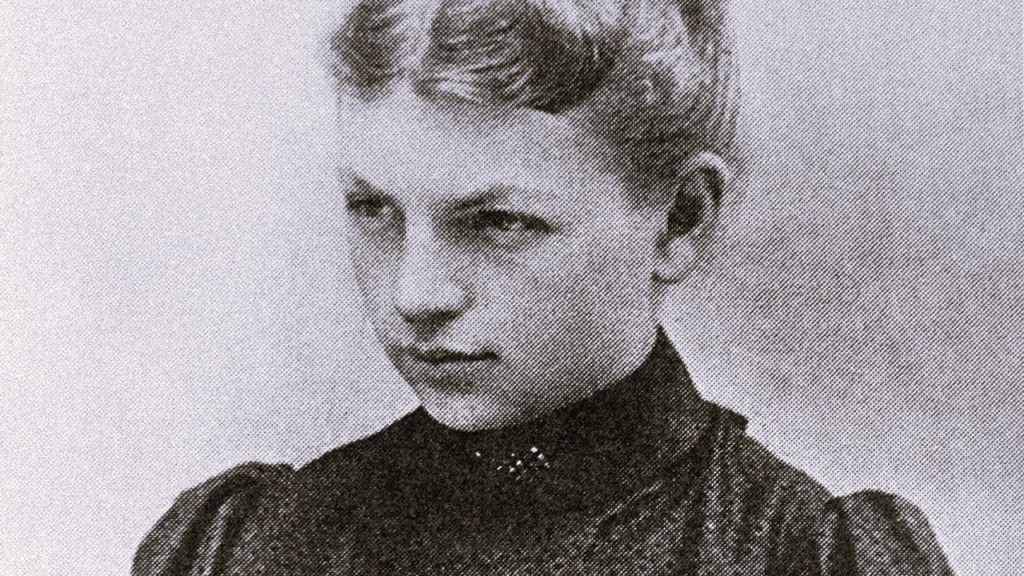

Today we sit with a woman who embodies both the soaring promise and crushing limitations of scientific ambition at the turn of the 20th century. Clara Immerwahr broke new ground as the first woman to earn a doctorate in chemistry from a German university, yet her story raises urgent questions about the price of scientific progress and the moral obligations that come with knowledge. In our age of dual-use research, weapons of mass destruction, and debates over scientific responsibility, her voice carries particular weight. Her tale isn’t merely one of personal triumph or tragedy—it’s a moral reckoning with the very nature of scientific endeavour.

Clara, thank you for joining us. I want to begin with your groundbreaking achievement—becoming the first woman to earn a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Breslau in 1900. That took extraordinary determination given the barriers women faced. What drove you to pursue science despite these obstacles?

The obstacles were immense, yes. Humiliating, even. I had to attend lectures as a mere “guest auditor”—can you imagine? Standing at the back of lecture halls whilst men half my age took their seats as legitimate students. But you see, my father was a chemist himself, and he taught me early that knowledge has no gender. When Max Planck declared that “Nature herself prescribed a role for women as mothers and housewives,” he revealed not natural law but his own limitations. Science needed me—needed all of us—whether it admitted so or not.

Your dissertation focused on the solubility of heavy metal salts—mercury, copper, lead, cadmium, zinc. Can you describe what drew you to this work?

Physical chemistry was emerging as the great unifying force—no longer would chemistry be mere taxonomy, a collection of disconnected facts. We were seeking the general principles that governed all chemical behaviour. My work examined the connections between conductivity, solubility, electrochemical potential… You must understand, this was detective work of the highest order. Each metal salt told a story about how atoms interacted, how energy flowed through solutions. I was particularly interested in whether electro-affinities were additive quantities—whether we could predict chemical behaviour by understanding these fundamental forces.

Your research required painstaking experimental work. What was it like working in those laboratories as the only woman?

Richard Abegg, my supervisor, was remarkably supportive—he saw talent where others saw an anomaly. But the daily indignities… colleagues who assumed my work was actually written by my male professors, laboratory assistants who questioned my every instruction. I wrote to Professor Abegg frequently about the “unfair treatment” I received. Yet when I defended my thesis in the university’s main hall, young women filled the galleries. They called me “our first female doctor.” That made every humiliation worthwhile.

You married Fritz Haber in 1901, shortly after completing your doctorate. Many have described this as the end of your scientific career. How did you view it at the time?

Fritz and I… we shared a passion for chemistry that I believed could sustain a true partnership. When he dedicated his thermodynamics textbook to me “in gratitude for silent co-operation,” I thought it meant something more than it did. I wrote to Abegg that I would return to the laboratory “once we become millionaires and can afford servants. I cannot even think about giving up my scientific work.” How naive I was.

What happened instead?

Hermann was born in 1902—a sickly child who required constant attention. Fritz’s career flourished whilst mine withered. By 1909, I could write to Abegg: “What Fritz has gained during these last eight years, I have lost, and what’s left of me fills me with the deepest dissatisfaction.” Fritz was the type of person beside whom anyone who doesn’t force their way even more recklessly will perish. And that was the case with me.

You did continue some scientific work through public lectures on “Chemistry and Physics in the Household.” How important was this to you?

Those lectures were my lifeline! I spoke to women’s organisations, housewives mostly, about the science surrounding their daily lives. People assume such work was trivial, but it was radical—bringing scientific thinking to half the population that university doors remained barred against. Science doesn’t belong only in ivory towers. When I explained how soap works or why copper pots conduct heat so well, I was democratising knowledge.

The Great War brought tremendous changes to your household. Fritz became deeply involved in developing chemical weapons. How did you view this transformation of science into warfare?

Here we must be precise about what actually happened versus what people now believe happened. Yes, Fritz threw himself into the war effort with characteristic obsession—eighteen-hour days, complete dedication to what he saw as patriotic duty. The Haber-Bosch process that made “bread from air” also made “gunpowder from air.” The same knowledge that could feed millions could also destroy them.

Did you oppose his work on poison gas?

The question haunts me still. Some accounts paint me as an outspoken pacifist who died in protest against chemical warfare. Others suggest I was initially proud of Fritz’s success, even reporting the Ypres attack to our son’s headmaster. The truth is more complicated. I was horrified by the suffering—the animal testing, the gruesome effects I witnessed. But I also felt duty to the Fatherland. The contradiction nearly destroyed me.

What was it like living with someone whose work you found morally troubling?

By then, Fritz and I were barely living together at all. I had quit the marital bedroom in 1902, never to return. We were strangers sharing a mansion. He was consumed by his work, his reputation, his place in history. I was… disappearing. When Richard Abegg died in that ballooning accident in 1910, I lost my confessor and champion. When Otto Sackur died in the laboratory explosion right before my eyes in 1914, I watched another brilliant mind snuffed out by science itself.

The night of 1st May, 1915—the night you died—Fritz was celebrating his promotion and the “success” at Ypres. What drove you to that final act?

That night crystallised everything—the complete destruction of what I had once been, what I had once hoped science could be. Whether it was discovering Fritz with Charlotte Nathan, or simply the accumulation of years of betrayal and loss… I took his service revolver and walked into our garden. I fired once into the air—a test, perhaps, or a warning. Then I turned it on myself. Hermann found me dying in his arms.

Looking back now, how do you want people to understand your story?

Don’t make me into a myth—neither saint nor victim. I was a scientist who compromised too much, who allowed institutional barriers and personal relationships to steal my voice. But also don’t ignore what my story reveals about science itself. Science is never neutral. Every discovery can serve life or death, creation or destruction. We who pursue knowledge bear responsibility for how it’s used.

What would you say to young women entering science today?

Never make yourself smaller for anyone else’s comfort. Never accept “silent co-operation” when what you deserve is full partnership. And never forget that with knowledge comes moral obligation. Science without conscience is the most dangerous force on earth. If my tragedy teaches anything, let it be that.

Do you have any regrets about your path?

I regret that I couldn’t find a way to be both scientist and woman without destroying one for the other. I regret that I didn’t speak more forcefully about the weapons research—not from pacifism, necessarily, but from a scientist’s duty to consider consequences. Most of all, I regret that my death became more famous than my life. I was a chemist first, a woman who pushed boundaries and made discoveries. Remember that.

Letters and emails

Our interview with Clara Immerwahr has sparked tremendous response from readers worldwide, particularly those facing similar questions about scientific responsibility, gender barriers, and moral courage in their own fields. We’ve selected five letters and emails from our growing community who wanted to ask her a little more about her life, her work, and what she might say to those walking in her footsteps.

Johanna M, 34, Patent Attorney, Berlin

Clara, as someone who navigates male-dominated spaces in IP law today, I’m curious about your coping mechanisms. When you faced those daily laboratory humiliations, did you develop any mental strategies or personal rituals that helped you persist? I imagine the psychological toll was immense, yet you kept going for years.

Johanna, your question strikes at something I’ve never spoken of publicly—the small, daily acts of defiance that kept my sanity intact. Yes, I developed rituals, though I’m not certain I recognised them as such at the time.

Each morning before entering the laboratory, I would recite to myself the periodic table—not as mere memorisation, but as a declaration of belonging. Hydrogen, helium, lithium… These elements answered to no man’s prejudice. They followed universal laws that cared nothing for my gender. When a colleague questioned my experimental setup or “corrected” my perfectly sound methodology, I would silently name the chemical processes occurring before us. Knowledge became my armour.

I also kept a private correspondence with Richard Abegg that went far beyond scientific matters—he became my confessor for every slight, every humiliation. Writing those letters, articulating the injustices, prevented them from poisoning me entirely. Without that outlet, I fear I would have internalised their view of my inadequacy.

But Johanna, I must warn you—these strategies sustained me for years, yes, but they also isolated me. I became so focused on proving my worth through intellectual superiority that I forgot to build alliances with other women who might have faced similar struggles. Don’t make my mistake of believing you must carry this burden alone. The coping mechanisms that preserve your sanity must never replace the fundamental work of changing the system itself.

Find your Richard Abegg—that trusted voice who validates your experience. But also find your sisterhood. I had neither the courage nor the opportunity to create that network. You do.

Gabriel C, 28, Chemical Engineering PhD Student, MIT

Dr. Immerwahr, your research on metal salt solubility seems foundational to modern electrochemistry and battery technology. If you could see today’s lithium-ion batteries or fuel cells, what aspects would most fascinate you? Do you think your approach to understanding electro-affinities could have accelerated these developments?

Gabriel! Lithium-ion batteries, you say? Oh, what I wouldn’t give to examine the electrochemical dance happening in those cells! You see, my work on heavy metal salts was precisely about understanding how ions behave in solution—their mobility, their affinity for electrons, the delicate balance between oxidation and reduction.

What fascinates me most is that you’ve essentially created reversible electrochemical reactions on demand. In my time, we observed these processes but couldn’t harness them so elegantly. The lithium ion shuttling between anode and cathode—that’s exactly the kind of predictable ionic behaviour I was trying to map with my solubility studies. I suspect the electrolyte chemistry must be exquisite. How do you prevent unwanted side reactions? The dendrite formation that plagued early electrochemical work?

And fuel cells! Converting chemical energy directly to electrical energy—we theorised about such possibilities, but the catalyst chemistry must be remarkable. I imagine you’ve solved the fundamental problem of reaction kinetics that stymied us. My approach to electro-affinities—understanding the inherent tendency of different elements to gain or lose electrons—could indeed have accelerated this work. If only I’d had access to modern analytical techniques to probe the electronic structure more deeply.

But Gabriel, tell me—do you consider the environmental implications of lithium mining, the geopolitical ramifications of battery dependence? My generation learned too late that scientific advancement without ethical foresight creates as many problems as it solves. Promise me you’re thinking beyond the electrochemistry to the human consequences.

Erna R, 45, High School Chemistry Teacher, Manchester

Clara, I teach teenage girls who often doubt whether they belong in science. When you gave those household chemistry lectures, what responses did you get from women who’d never seen themselves as capable of scientific thinking? How did you make complex concepts accessible while still respecting their intelligence?

Erna, those household chemistry lectures were perhaps the most rewarding work of my career—more meaningful, in many ways, than my formal research. The women who attended… their faces when they realised they’d been conducting chemistry experiments every day without knowing it! Kneading bread dough and watching gluten networks form, observing how soap molecules surround grease—suddenly they weren’t merely housewives, they were practical chemists.

I remember one woman, a baker’s wife, who asked why her bread rose inconsistently. When I explained how temperature affects yeast metabolism, how carbon dioxide bubbles create texture, she began experimenting deliberately—adjusting temperatures, timing fermentation. Within months, she was teaching other women. That’s when I knew I’d succeeded—not when they understood my explanations, but when they began asking their own questions.

The key, Erna, was never talking down to them. I refused to use simplified language that implied simplified minds. Instead, I built bridges from their existing knowledge. When explaining molecular motion, I started with steam rising from their cooking pots. For chemical bonding, I used the way sugar dissolves in tea—familiar phenomena that revealed universal principles.

But what moved me most were the mothers who brought their daughters. I watched twelve-year-old girls’ eyes widen when they realised that chemistry wasn’t some mysterious masculine domain—it was the science of their everyday world. Those girls would be women now. I hope some pursued formal education because of those afternoons.

Tell your students this: science isn’t something that happens to them—it’s something they’re already doing. They just need permission to call themselves scientists.

Raquel C, 29, Bioethics Researcher, Singapore

Your story resonates deeply with current debates about dual-use research—think gain-of-function studies or AI development. If you were advising today’s scientists working on potentially dangerous technologies, what institutional safeguards or personal ethical frameworks would you recommend? How can we prevent another ‘Fritz Haber dilemma’?

Raquel, your question cuts to the heart of my greatest failure—and perhaps my most important lesson. Dual-use research… yes, that captures it perfectly. Fritz genuinely believed his nitrogen fixation would end world hunger, that even his poison gas would shorten the war and save lives. The road to hell, as they say, is paved with such noble intentions.

If I were advising today’s scientists, I would demand institutional structures that Fritz and I never had. First, mandatory ethics review boards—not just for human subjects, but for any research with potential military applications. These boards must include voices beyond the scientific community: ethicists, historians, affected communities. Scientists alone cannot judge the implications of their work.

Second, researchers must have legal protection for conscientious objection. Fritz’s laboratory was funded by military contracts—once committed, withdrawal became nearly impossible. Scientists need the right to step away when research crosses their moral boundaries without destroying their careers.

But most crucial—and this is where I failed most profoundly—is the obligation to speak publicly about potential misuse. I knew the horrific effects of chlorine gas. I witnessed the animal testing, saw the gruesome results. Yet I remained silent, bound by loyalty and social convention. That silence was complicity.

Your generation must refuse such complicity. When you see your gain-of-function research or AI development moving toward dangerous applications, you must sound the alarm—loudly, publicly, regardless of career consequences. The scientific community needs its own whistleblower protections, its own internal resistance movement.

Because Raquel, once the genie escapes the bottle, good intentions become irrelevant. Prevention is the only ethical response.

Bryan B, 52, Science Journalist, Toronto

Clara, there’s been scholarly debate about whether your opposition to chemical weapons was as clear-cut as some portray. Looking back, do you think nuanced positions on morally complex issues get oversimplified by history? How would you want future generations to understand the difference between principled compromise and moral cowardice?

Bryan, you’ve identified precisely what troubles me most about how my story has been told. History demands heroes and villains, saints and sinners—but I was neither. I was a woman caught between competing loyalties, evolving convictions, and impossible circumstances.

Yes, there’s evidence I initially felt pride in Fritz’s early war work. I may have boasted to Hermann’s headmaster about the “success” at Ypres—though whether from genuine conviction or desperate social performance, I can no longer say. The truth is, my opposition to chemical weapons wasn’t born fully formed like Athena from Zeus’s head. It grew from horror, from witnessing suffering, from the gradual recognition that we’d crossed a line from which there was no return.

But here’s what troubles me about scholarly “debate” over my moral clarity—it often serves to diminish the very real evolution that moral courage requires. Must opposition be absolute from the first moment to be legitimate? I was a German citizen in wartime, a scientist’s wife, a mother trying to hold her family together. My patriotism and my revulsion existed simultaneously for months before one finally conquered the other.

The difference between principled compromise and moral cowardice? Principled compromise acknowledges the complexity while working toward the right outcome. Moral cowardice uses complexity as an excuse for inaction. I spent too long in that second category, paralysed by competing obligations.

Future generations should understand this: moral clarity is often a luxury of hindsight. What matters isn’t having perfect convictions from the start—it’s having the courage to act when those convictions finally crystallise, even when the personal cost is devastating.

I was flawed, Bryan. But my flaws don’t invalidate my ultimate stand. They make it human.

Reflection

As Clara’s voice fades, we’re left with questions that echo powerfully today. Her story isn’t simply about a woman crushed by sexist institutions or a pacifist destroyed by militarism—though those elements exist. It’s about the fundamental tension between scientific ambition and moral responsibility, between personal fulfilment and societal duty, between the promise of knowledge and its potential for devastating misuse.

In our age of CRISPR gene editing, artificial intelligence, and climate engineering, Clara Immerwahr’s moral tribunal remains achingly relevant. Her tragedy wasn’t that she was the first woman to earn a chemistry doctorate in Germany—it was that her scientific voice was silenced just when the world most needed it. As we reckon with the dual nature of scientific progress, her warning resonates: science without conscience remains humanity’s most dangerous gamble.

Clara made war personal by living it, breathing it, and ultimately dying from it. Her story demands that we do the same—that we never again allow the pursuit of knowledge to proceed without reckoning with its human cost.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind — and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way — whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher — please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion — even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview is a dramatised reconstruction based on extensive historical research, including Clara Immerwahr’s documented correspondence with Richard Abegg, contemporary accounts of her life and work, and scholarly analysis of her tragic circumstances. While her words and perspectives are imagined, they are grounded in verified biographical details, her known scientific contributions, and the documented social constraints faced by women in early 20th-century German academia. Any dialogue attributed to Dr. Immerwahr represents an interpretation of her likely views based on available evidence, not direct quotations from historical sources.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to Bob Lynn Cancel reply