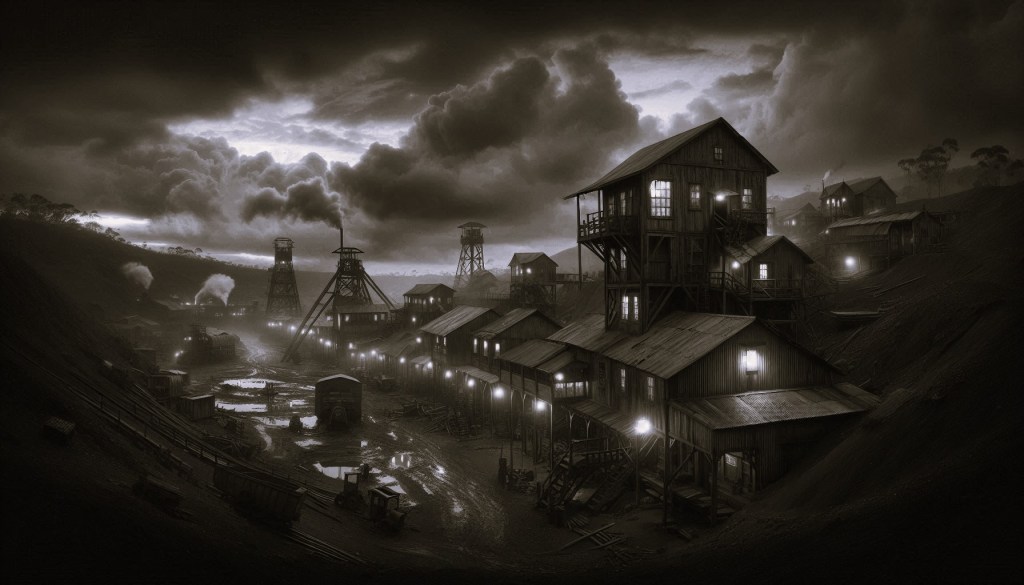

Oriental Mine Quarters, Kolar Gold Fields

18th February, 1886

My Dearest Mary,

I received your letter of November 15th yesterday morning, and I confess I have not moved from this chair since reading those terrible words. Our little Edward. Our precious boy. Gone.

The paper grows wet beneath my hand as I write. I cannot seem to stop the tears, Mary. They come without warning, in the middle of conversations with other miners, during the hottest part of the day when even breathing requires effort. MacLeod found me weeping over the ore samples yesterday and sent me back to quarters, saying I was “unfit for duties.” He does not know why I weep. I have told no one here about our loss.

How can I write of other matters when our child lies cold in Yorkshire earth whilst his father labours uselessly beneath this burning sun? You held him as he died, Mary. You held our boy whilst I counted gold specks in foreign rock. What manner of father abandons his family for such fool’s dreams? What manner of husband leaves his wife to face such sorrows alone?

I should have been there. God forgive me, I should have been there to carry his small coffin, to comfort you in your grief, to dig his grave with my own hands rather than leave such sacred duties to neighbours’ charity. Instead I pursued phantom wealth in this accursed place whilst death claimed our innocent child. The guilt burns in my chest worse than the fever that has plagued me these past weeks.

Yes, I am ill, my love. The cough that began during the monsoon has worsened considerably, bringing with it blood-tinged sputum that Dr. Stewart says indicates “lung inflammation common to miners in tropical climates.” I wake each morning feeling as though invisible hands squeeze my chest, and the simplest tasks leave me gasping like a landed fish. My left shoulder, weakened by the old Middleton injury, now pains me constantly, making it difficult to swing a pick with proper force.

The medicine Dr. Stewart prescribes costs more than I earn in a week. I have been forced to borrow money from Hartwell – the fellow from Barnsley I mentioned in earlier letters – to pay for treatments that provide only temporary relief. The debt weighs upon me almost as heavily as my guilt over Edward’s death, for I know each shilling borrowed delays my return home by that much longer.

The Oriental Mine grows worse with each passing month. The promised American pumping equipment never arrived – we learned last week that the machinery was diverted to a more profitable operation in Burma, leaving us to battle the perpetual flooding with implements suited for a village well. Our workforce has dwindled to fewer than thirty men, mostly newcomers like myself who lack the experience to secure positions at the productive mines. MacLeod speaks constantly of closure unless productivity improves, yet how can we improve output when we spend more time pumping water than extracting ore?

Three more Europeans have died since Christmas. Curnow from Cornwall succumbed to the fever that seems to claim men regardless of their strength or constitution. Bennett from Cardiff developed what Dr. Stewart termed “tropical consumption” – a wasting disease that reduced him from a robust fourteen-stone man to a skeletal shadow within two months. Most tragically, young Peters from Birmingham – barely nineteen years old – died from complications following a minor injury that became infected in this climate where wounds refuse to heal properly.

I fear I may be following their path, Mary. The cough grows stronger each week, my weight continues to drop despite the starchy diet they provide, and I find myself struggling to complete even half a day’s work. Yesterday I collapsed in the shaft from what I thought was mere exhaustion, but when I awoke in the hospital, Dr. Stewart’s expression suggested more serious concerns than simple fatigue.

The company’s attitude towards sick miners has become increasingly harsh as profits decline. Men who cannot maintain productivity are quickly dismissed and given passage back to the nearest port – but only if they can prove sufficient funds for the journey. Those who fall ill whilst in debt to the company, as I now am, face a more uncertain fate. Dr. Stewart mentioned, with obvious discomfort, that the cemetery behind the European quarter contains more miners than managers, and most died owing money rather than having earned it.

I have calculated my debts against my meagre earnings, Mary, and the arithmetic fills me with despair. Between medical expenses, accumulated accommodation costs, and the money borrowed for basic necessities, I owe the company nearly forty pounds – more than I could earn in six months even if the Oriental Mine returned to full productivity. The truth I have avoided writing until now is that I cannot afford passage home. Even if I recovered my health tomorrow and worked without wages until Christmas, the debt would barely diminish.

MacLeod has suggested I might apply for transfer to one of the more successful operations – Champion Reef or Mysore Mine – where experienced miners can earn wages sufficient to clear such debts within a year or two. But such positions require robust health and a clean record with the company, neither of which I possess. My persistent cough and recent collapses have marked me as a poor risk, whilst my mounting debts make me a liability rather than an asset.

I think constantly of Edward’s final days, wondering if I might have made some difference had I been present. Could I have afforded better medicine? Might additional coal have kept him warmer during those terrible nights when fever burned through his small body? The questions torment me, Mary, because I know the gold I pursued so desperately could have provided the comfort our dying child needed.

Your letter speaks of your own struggles – the additional mending work, the harsh winter, the financial strain of Edward’s illness and funeral. Each word cuts me deeper than any mining accident could, for I see clearly how my selfish ambitions have left you to bear impossible burdens alone. You needed your husband during our child’s final hours, not a pile of debts from a failed colonial adventure.

The electric lights that once amazed me now seem to mock my predicament. This technological marvel illuminates a world of human misery, where desperate men die far from home whilst their families struggle in poverty. The “Little England” that so impressed me upon arrival reveals itself as a cruel parody – English order imposed upon alien soil for the profit of distant shareholders who never witness the cost in human suffering.

I have been writing to you of my illness and despair, yet I must also write of love and hope, though both seem distant as morning stars. Every laboured breath reminds me of the life I abandoned in Yorkshire – your gentle touch when I returned exhausted from Middleton pit, the children’s laughter filling our small house, the simple contentment of family gathered around our modest table. Such memories sustain me through the darkest hours when physical pain and emotional anguish threaten to overwhelm entirely.

Tell Margaret and young William that their father loves them beyond measure, and that every remaining day of my life will be devoted to atoning for my absence during their brother’s final illness. I pray they will forgive their foolish father for chasing dreams whilst tragedy struck our family. If I survive this place – and I confess the prospects grow dimmer each week – I will spend whatever years remain making amends for my terrible choices.

Should this illness claim me, Mary, know that my final thoughts will be of you and our children. The lock of Edward’s hair you sent rests always against my heart, a sacred reminder of the innocent life lost whilst I pursued worthless ambitions. I have written instructions for Dr. Stewart to ensure my few possessions reach you, though they amount to little more than a few books and the mining tools that have served me so poorly in this foreign earth.

Forgive me, my beloved wife. Forgive a husband who failed to protect his family, who chose distant gold over present love, who was absent when needed most. I do not deserve your forgiveness, yet I beg for it with the desperation of a dying man seeking salvation.

If God grants me recovery and opportunity to return home, I will never again place ambition above family. But if He calls me to join our little Edward in that far country where mining accidents and tropical fevers hold no dominion, know that I depart this world loving you more than life itself, and regretting every moment spent away from your side.

Your devoted and remorseful husband,

William Baldwin

P.S. – I can write no more tonight. The coughing has worsened, and my hand shakes too violently to guide the pen properly. Dr. Stewart will post this letter for me, as I am too weak to walk to the postal office myself. Kiss our remaining children and tell them their father’s greatest treasure was never gold, but the family he left behind.

◄ Go back to part 6 | Continue to part 8 ►

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to Violet Lentz Cancel reply