The Coast of New Albion (California) – 17th June, 1579

The salt spray caught my face as I pressed my palm against the weathered hull of the Golden Hind, feeling for the telltale give that would signal rot beneath the tar. Three years we had been at sea, three years since we’d slipped our moorings at Plymouth under cover of December darkness, and still she held true. My ship—for that is how I had come to think of her, though Captain Drake might take issue with such presumption from a mere carpenter.

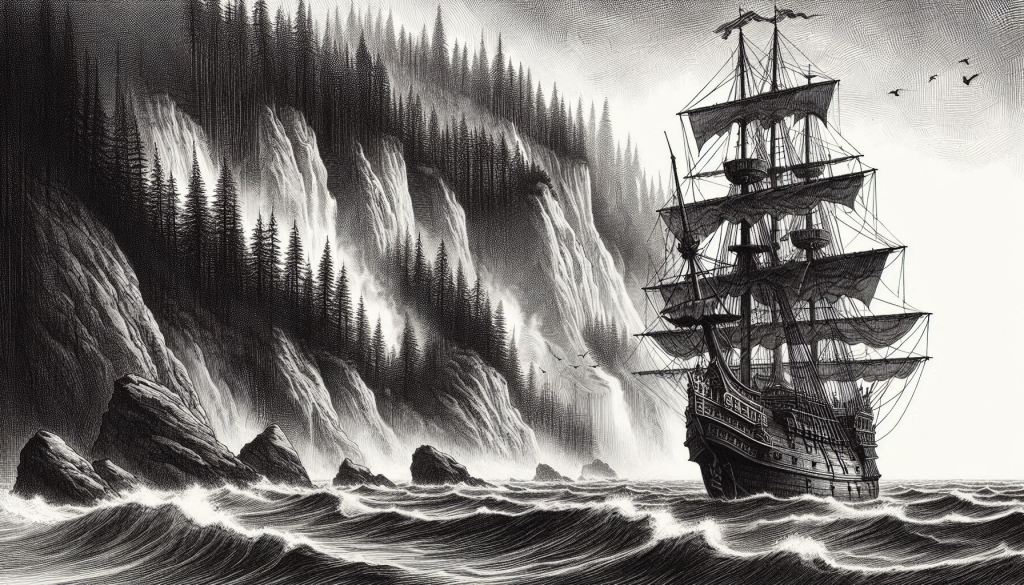

The morning of June the seventeenth, in this year of our Lord fifteen hundred and seventy-nine, found us anchored in waters so blue they seemed to mock the grey Atlantic we had known all our lives. The coastline before us rose in magnificent cliffs crowned with forests the like of which I had never seen, their green so deep it appeared almost black in the early light. This land that our captain had proclaimed “New Albion” stretched northward beyond sight, wild and untamed as God had made it.

I drew my knife and scraped at a section where the wood had darkened, studying the shavings that curled away beneath my blade. Still sound, praise be. My hands moved with the certainty born of countless such examinations, fingers reading the timber’s secrets as surely as a scholar might parse Latin text. These hands—steadied by years of matching mallet to chisel, of shaping recalcitrant oak to my will—had kept us afloat through storms that had torn other vessels asunder.

“Hart!” The voice belonged to Thomas Fleming, our master gunner, a Devon man like myself though from Tavistock rather than my own Totnes. “Captain wants the pinnace made ready for landing. Says we’re to make formal claim of this territory for Her Majesty.”

I nodded, wiping my blade clean before sheathing it. The pinnace would need examining; she had taken a beating in the crossing of that great southern sea the Spanish called Pacífico. Peaceful, they named it, though we had found precious little peace in its vastness. Week upon week of nothing but water stretching to every horizon, until a man began to wonder if he had dreamed of land entirely.

As I made my way to where the smaller craft was secured, I found myself reflecting upon Fleming’s easy assumption that I would set aside my current work without question. It was not arrogance on his part—we had sailed together too long for such niceties to matter—but rather the recognition of something I had only lately begun to understand about myself. Perhaps it was the extraordinary nature of our voyage, or the weight of being so far from everything familiar, but I had found myself given to contemplation in recent months.

What manner of man was I, truly? The question had begun to plague me as we rounded the great cape at the bottom of the world, where the Atlantic and Pacific met in fury. In those terrible days when every timber groaned and our lives hung upon the competence of my repairs, I had been forced to confront not merely the ship’s mortality but my own.

The pinnace’s hull showed stress along her starboard strakes, hairline cracks that spoke of the battering she had endured. I ran my thumb along one such fissure, feeling its depth, gauging whether it would hold for the landing or require immediate attention. This was my gift, I supposed—this ability to understand what wood would bear and what it would not, to coax strength from oak that had already given so much.

But was it truly my favourite thing about myself? The steadiness of these hands that had learned their craft in my father’s shop behind Totnes market, that had shaped wheel spokes and plough handles before ever they touched ship’s timber? I flexed my fingers, studying the scars that mapped thirty-two years of working with sharp tools and unforgiving materials. Each mark told a story—the ragged line across my left palm from the day I had tried to catch a falling adze, the constellation of small cuts on my knuckles from years of shaving joints to perfect fit.

Young Willem Janzoon, the Dutch lad we had taken aboard in the Spice Islands, approached with oakum and tar. He moved with the careful deference of one still learning his place among men who had sailed half the world together.

“Master Hart,” he said in his careful English, “shall I begin caulking whilst you work the timber?”

I considered the boy—for at seventeen, he seemed scarce more than that to my eyes. He had begged passage with us when we had put in for water and provisions, speaking of a desire to see England and make his fortune there. Drake had been inclined to refuse, but I had spoken for the lad. Something in his earnest manner had reminded me of my own younger self, eager to prove worthy of the craftsmen around him.

“Aye, Willem, but mind you press it well home. This lady must carry us safe to shore and back again.”

He nodded soberly and set to his work, and I found myself watching his technique with a critical eye. The boy had clever hands, I would grant him that, but he lacked the instinctive understanding that came only with years of practice. He caulked with his mind rather than his fingertips, thinking through each motion rather than trusting to experience.

Perhaps that was what I valued most about myself—not merely the skill in my hands, but the hard-won knowledge that guided them. Every joint I had cut, every plank I had shaped, every repair I had wrought had added to a store of understanding that no book could convey. When the great storm had struck us off the coast of Chile, when green water had poured through a split seam and threatened to send us all to the bottom, it had been this accumulated wisdom that had saved us. Not strength alone, nor dexterity, but the deep certainty of knowing exactly what the emergency required and how best to provide it.

The morning sun climbed higher, warming my back as I worked to reinforce the pinnace’s damaged strake. Around me, the ship came alive with the familiar sounds of a crew preparing for significant endeavour. Drake himself appeared on deck, resplendent in his finest doublet despite the early hour. Our captain understood the power of spectacle; when he claimed this land for England, he would do so with all the ceremony the moment deserved.

As I watched him move among the men, distributing orders with that peculiar mixture of authority and camaraderie that had carried us through three years of hardship, I felt a familiar surge of loyalty. Not blind obedience—I was Devon born and bred, too stubborn for that—but rather a deep appreciation for a leader who had earned his men’s trust through competence and shared danger.

This, too, might be counted among my better qualities: my steadfastness to those who had proven themselves worthy of it. I thought of the countless times I had set aside my own comfort to ensure the ship remained sound, working through watch changes when exhaustion made my hands shake, because the safety of my shipmates depended upon my diligence. When John Veysey had fallen sick with fever off the coast of Peru, I had taken his watches as well as my own rather than see the work fall to men already pressed beyond endurance.

But loyalty, whilst admirable, felt too simple an answer to my question. Any man worth his salt would stand by his comrades in extremity. What set one apart was not the willingness to do one’s duty, but the manner in which that duty was discharged.

A shout from the masthead drew my attention upward. The lookout pointed toward shore, where smoke rose from what might have been signal fires. The natives of this land, whoever they might be, were aware of our presence. I wondered what they made of our great ship with her towering masts and spread of canvas. Did we appear as wondrous to them as their pristine coastline did to us?

The thought led me to consider another facet of my character that I had only recently begun to recognise. For all that I was a practical man, concerned with the solid realities of wood and iron, I possessed what might charitably be called imagination. Not the flighty fancy of poets, but rather the ability to see beyond the immediate task to its greater significance.

When I shaped a timber, I saw not merely the replacement of a damaged piece, but the continuation of the ship’s story. Each repair became part of her history, a chapter in the ongoing tale of her survival. The strake I patched today might one day be examined by some future carpenter, who would read in my work the story of this moment—the morning we claimed a new world for England.

This capacity to perceive the lasting consequence of present action had served me well throughout our voyage. Where other men might see only the tedium of constant maintenance, I recognised the sacred trust placed in my hands. The lives of sixty-eight souls depended upon my ability to keep our vessel sound, and I found profound satisfaction in that responsibility.

Perhaps this was what I treasured most about myself: not any single skill or virtue, but rather the way in which I approached my calling. I was no mere ship’s carpenter, content to perform the minimum required for my wages. I was a craftsman in the truest sense, one who found in good work its own reward.

The pinnace was nearly ready, her hull once again tight and seaworthy. Willem had proven apt with the caulking, driving the oakum home with proper firmness. The lad would make a fine carpenter in time, given proper guidance. Perhaps, when we returned to England—God willing that we should see those shores again—I might take him as apprentice. The thought pleased me more than I would have expected.

Captain Drake approached, his boots ringing on the deck. “How fares our small boat, Master Hart? Can she bear us safely to that unknown shore?”

“Aye, Captain,” I replied, running my hand once more along the repaired strake. “She’ll serve you well, as she has done these three years past.”

He clapped me on the shoulder, a gesture I valued for its rarity. Drake was not given to casual familiarity, but our long voyage had earned certain privileges.

“Your work has been the salvation of us all, Elias. When we set our feet again on English soil, I shall see that Her Majesty knows of your service.”

I felt heat rise in my cheeks at such praise, but managed to keep my voice steady. “I have only done what any carpenter worth his tools would do, sir.”

“Nay,” he said, fixing me with that penetrating gaze that had cowed Spanish admirals. “You have done far more than duty required. You have given us your very best at every turn, asking nothing in return save the chance to continue serving. That is the mark of a true craftsman.”

After he had gone to oversee the final preparations for landing, I remained by the pinnace, turning his words over in my mind. A true craftsman—was that indeed what I had become? Not simply a man who worked with his hands, but one who brought to that work a devotion that transcended mere competence?

I thought of the countless hours I had spent in contemplation of some particularly challenging repair, studying the problem from every angle until the solution revealed itself. I recalled the deep satisfaction I felt when a joint fitted perfectly, when disparate pieces of timber became something greater than their sum. This was more than skill—it was a form of love, though I might never have named it so before this moment.

The sun had reached its zenith when the boats finally pulled away from the Golden Hind’s side, carrying Captain Drake and twenty men toward the beach where they would plant England’s flag in New Albion’s soil. I watched from the rail as they grew smaller with distance, my pinnace riding steady beneath them despite the ocean swell.

As the ceremony unfolded on that distant shore—too far for me to make out details, but close enough to see the bright flash of the ensign as it was raised—I found myself possessed of a curious peace. I had answered my own question, though perhaps not in the way I had expected when it first began to trouble me.

My favourite thing about myself was not any single quality, but rather the way in which all my qualities worked together in service of something larger than my individual desires. My steady hands, my loyalty to my shipmates, my craftsman’s pride—these were not separate virtues but facets of a single commitment to excellence in all things.

Tomorrow we would weigh anchor and continue our journey home, carrying with us the knowledge that we had circumnavigated the globe and claimed new territories for our sovereign. The Golden Hind would bear us safely across those vast Pacific waters, her hull kept sound by my constant vigilance.

And I would continue to find, in the honest work of my hands and the devotion of my heart, a satisfaction deeper than any treasure Drake’s raids had won us. For I was Elias Hart of Totnes, ship’s carpenter, and I had learned to love the man I had become.

The End

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to Tony Cancel reply