Runnymede, England – 15th June, 1215

The bronze grows warm beneath my fingers as I grip it, this ancient stylus that has known the touch of so many hands before mine. Six centuries it has served, first in the hands of Roman administrators who carved their careful records into wax tablets across this very land, then passed through generations of my brothers in Christ, each adding their own wear to its surface, each sharpening its point anew when the bronze grew dull with use.

Today, on this fifteenth day of June in the year of our Lord twelve hundred and fifteen, I hold it with trembling reverence as I prepare to inscribe words that may well reshape the very foundations of our realm.

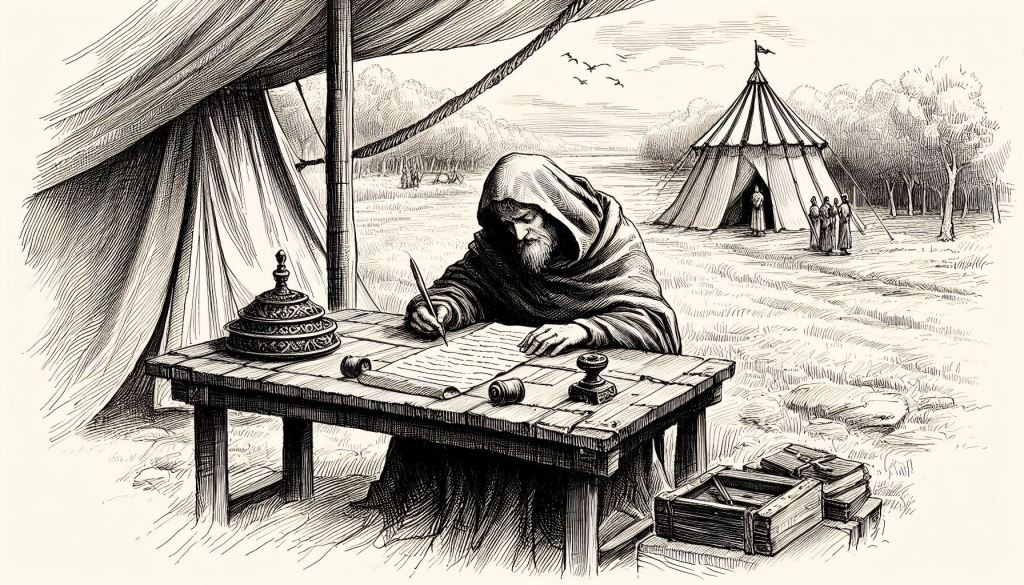

The water-meadow of Runnymede stretches before me in the early morning mist, the Thames flowing steady and silver beyond the gathering pavilions. Already, the barons’ men move about like ants disturbed from their hill, their mail gleaming dully in the pale light that filters through the river fog. King John’s banner hangs limp in the still air, whilst across the meadow, the rebel barons have arranged their own standards in a show of defiant unity that would have been unthinkable mere months ago.

I sit beneath a canvas shelter that my lord Archbishop Stephen Langton has commanded be erected for our work. Before me lie the wax tablets upon which we have laboured these past days, scratching and re-scratching the sixty-three clauses that shall form this Great Charter. My stylus has traced each word countless times, its flat end erasing, its pointed tip inscribing anew as we refined the language that must bind a king to law.

“Brother Godwin,” comes the gentle voice of my lord Archbishop, and I look up to see his weathered face creased with the weight of these momentous days. “Are you ready to begin the final copy?”

I nod, though my heart pounds like a smith’s hammer against my ribs. “Aye, my lord. The vellum is prepared, the ink mixed fresh this morning.”

He places a hand upon my shoulder, and I feel in his touch the gravity of this moment. “Remember, good brother, that what you write today shall echo through generations yet unborn. Let your hand be steady, your letters clear.”

As he moves away to resume his negotiations between the king and his rebellious barons, I turn my attention to the pristine vellum that awaits my pen. But first, I take up my stylus once more, running my thumb along its familiar weight. How many laws has this bronze tool helped to shape? How many charters, how many writs, how many records of justice dispensed or withheld?

I close my eyes and fancy I can feel the ghosts of all those previous scribes whose fingers have worn smooth this ancient metal. Brother Aldric, who used it to copy the Saxon law codes when the Normans first came. Brother Osmund, who scratched out ecclesiastical correspondence during the reign of the first Henry. And before them, nameless monks who preserved what learning they could through the dark years after Rome’s legions departed these shores.

But deeper still, I sense the presence of that first scribe—Roman, perhaps, whose precise Latin hand carved tax assessments and administrative orders when this land was still a distant province of an empire that thought itself eternal. That unknown man could never have imagined that his simple bronze stylus would one day help inscribe a document that would dare to place limits upon the power of kings.

A commotion from the king’s pavilion draws my attention. I see John himself emerge, his face dark as a thundercloud, flanked by his advisors who scuttle about him like worried hounds. Even from this distance, I can read the reluctance in his bearing, the barely contained fury at being brought to heel by his own subjects. Yet here he stands, at Runnymede, because even a king cannot govern without the consent of those he rules—a truth that shall be carved into law this very day.

I dip my pen in the fresh ink and begin.

Johannes Dei gratia rex Angliae…

John, by the grace of God, King of England. How the words flow from my stylus onto the vellum, each letter formed with the careful precision that years of training have instilled in my hand. Yet as I write, I cannot help but think of how this very formula—this divine right that kings claim—is about to be circumscribed by the clauses that follow.

The work is painstaking. Each word must be perfect, each letter clear and strong. There can be no ambiguity in a document of such import, no smudged ink or uncertain strokes that might later be used to dispute its meaning. My stylus has taught me patience over these years—how many times have I erased and begun again when working on my wax tablets? How many rough drafts has this ancient tool helped me perfect before committing ink to precious vellum?

As the morning wears on, I lose myself in the rhythm of the work. Around me, the drama of kingship and rebellion plays out, but I am consumed by the careful forming of each letter, each word that shall bind this unruly monarch to the rule of law. My stylus lies beside my writing hand, within easy reach should I need to make notes upon my wax tablet as the final negotiations proceed.

“Nullus liber homo capiatur, vel imprisonetur, aut dissaisiatur…“

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions… The words seem to burn themselves into the vellum as I write them. Here is the very heart of the matter—the promise that justice shall not be the mere whim of royal pleasure, but subject to the lawful judgement of peers and the law of the land.

I pause in my writing and take up my stylus, turning it between my fingers as I have done countless times before. Six hundred years, and still its bronze gleams where my thumb rubs against it. Still its point remains sharp enough to score clean lines in wax. Still it serves the cause of preserving law and learning, just as it did when Roman clerks used it to record the decisions of governors and magistrates in this same land.

There is something profoundly moving in this continuity—this unbroken chain of law and scholarship that stretches back through Saxon king and Norman conqueror to the eagles of Rome itself. Each generation has added its own understanding to the great work of justice, each has refined and improved upon what came before. And now, with God’s grace, we add our own contribution to that eternal struggle to bind power to law.

The afternoon brings fresh urgency to our work. Word comes that the king grows increasingly restive, that his advisors whisper of the dangers of signing such a charter. But the barons hold firm, and my lord Archbishop moves between the factions like a shepherd tending fractious flocks, his wisdom and moral authority the only force keeping this fragile peace from shattering.

I write on, my hand cramping with the effort, my eyes stinging from the close work. But with each clause I complete, I feel the weight of history settling around us like a mantle. This is no mere political compromise we craft here, but something that shall endure long after John’s bones have crumbled to dust, long after these proud barons have been forgotten.

As evening approaches, I near the end of my labour. The sixty-third and final clause takes shape beneath my pen, sealing this great work with the promise that it shall be observed faithfully by all. My stylus catches the last light of day as I set it beside the completed charter, its bronze surface seeming to glow with the satisfaction of work well done.

Tomorrow, this document shall bear the royal seal, and copies shall be made for distribution throughout the realm. But tonight, as I clean my ancient stylus and prepare it for whatever work tomorrow may bring, I am struck by the profound truth that some things endure not through their grandeur, but through their daily usefulness.

This simple tool has served justice for six centuries, and God willing, it shall serve for six centuries more. Kings may rise and fall, empires may crumble, but the need for clear writing, for careful record-keeping, for the preservation of law and learning—these needs are eternal. And so long as there are monks to tend the flame of knowledge, so long as there are scribes to set down the words that bind men to justice, there shall be need for tools such as this ancient stylus that rests now, warm and familiar, in my grateful palm.

The Magna Carta lies before me, complete and perfect, ready to change the world. And my stylus, older than cathedrals, humbler than crowns, prepares once more to serve whatever cause tomorrow may demand.

The End

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to The Sealing of the “Magna Carta” – Ingliando Cancel reply