The Geography Teacher Who Changed the World

In 1950s America, when computers were room-sized monsters requiring teams of specialists to operate, an eighth-grade geography teacher made a prophetic observation. “Mary Allen, when you grow up, you ought to be a computer programmer,” she told her student. That student, Mary Allen Wilkes, would go on to write the operating system for what many consider the world’s first personal computer—and become the first person to use one at home.

Born in Chicago on 25th September 1937, Wilkes initially harboured dreams of becoming a lawyer. She graduated from Wellesley College in 1959 with a degree in philosophy and theology, her mind set on a legal career. Yet the harsh realities of 1950s sexism soon intervened. Friends and mentors discouraged her from pursuing law, warning that the challenges women faced in the field were insurmountable. At that time, women who managed to complete law school were typically relegated to positions as legal secretaries or law librarians—hardly the professional equality she sought.

From Philosophy to Programming

Rather than accept defeat, Wilkes pivoted with remarkable prescience. On graduation day in 1959, her parents drove her directly to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she applied for—and immediately received—a position as a computer programmer. Her philosophy degree, far from being a hindrance, proved an unexpected asset. The symbolic logic training inherent in her philosophical education provided exactly the precise, methodical thinking required for early programming.

This wasn’t unusual for the era. Programming was still such a nascent field that formal computer science degrees didn’t exist. Employers looked for candidates with logical minds capable of exacting precision, and women were often considered particularly suited to this detailed work. Indeed, a significant portion of early programmers were women, as the meticulous nature of coding—requiring concise, precise instructions given the limited memory of early computers—was viewed as naturally fitting feminine capabilities.

The LINC Revolution

Wilkes’s career trajectory changed dramatically in June 1961 when she joined the Digital Computer Group at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory. She arrived just as work was beginning on an ambitious project under the direction of Wesley A. Clark—the Laboratory Instrument Computer, or LINC. Clark had previously designed Lincoln’s TX-0 and TX-2 computers, but his vision for LINC was revolutionary.

The LINC represented a fundamental departure from existing computing paradigms. Unlike the massive, remote, centrally-controlled machines that dominated the landscape, Clark envisioned a computer that would be small, interactive, and operated under the direct control of individual users. His design criteria were deliberately user-centred: the machine had to be easy to program, easy to communicate with during operation, easy to maintain, and capable of processing biomedical signals directly. With characteristic wit, Clark added two practical constraints—it couldn’t be too high to see over, and it must cost no more than $25,000, the threshold a laboratory director could approve without higher-level authorisation.

Designing the Future

Wilkes’s contributions to LINC development were foundational. She simulated the operation of the LINC during its design phase on the TX-2, designed the console for the prototype, and wrote the operator’s manual for the final console design. More significantly, she developed what would become the computer’s operating system—a series of programs called LINC Assembly Programs, or LAP.

Starting with the original LAP and continuing through successive iterations up to LAP6, Wilkes created what was arguably one of the first interactive operating systems for a personal computer. LAP6, in particular, represented a masterpiece of efficient programming. Running on a computer with just 2,048 12-bit words of memory, it provided full facilities for text editing, automatic filing and file maintenance, and program preparation and assembly. The system was segmented into 11 “layers” held on tape and read into memory as needed—a sophisticated approach to memory management that prefigured modern operating systems.

The First Home Computer User

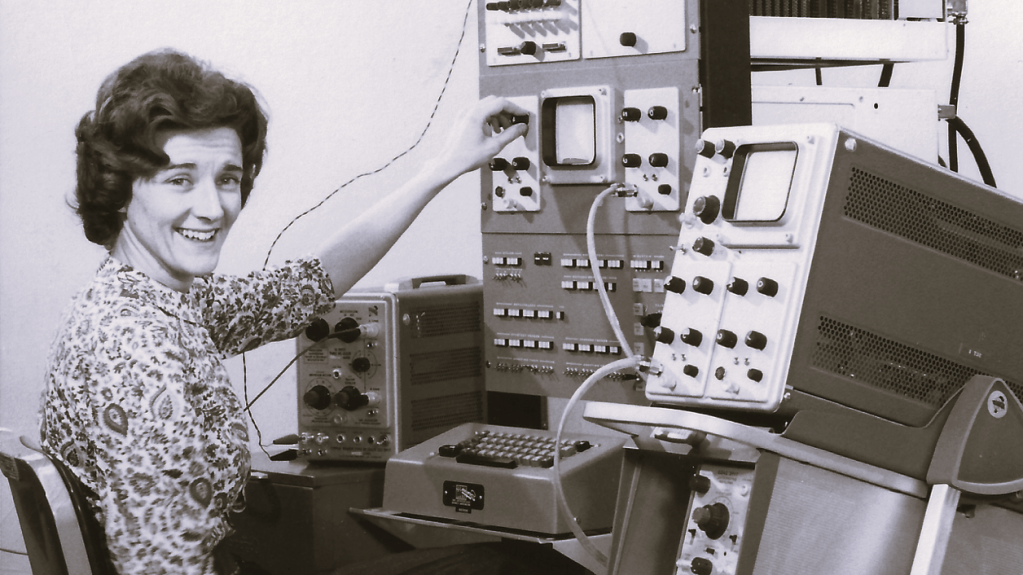

In 1964, the LINC team moved from Lincoln Laboratory to Washington University in St. Louis. Wilkes faced a dilemma—she wanted to continue her work but was reluctant to relocate because her mother was ill. The solution was unprecedented: Washington University shipped a LINC computer to her parents’ home in Baltimore. In 1965, Wilkes became the first person in history to have a personal computer in her home.

“My father, who was a clergyman, thought this was fabulous. He loved having the LINC in the living room,” Wilkes later recalled. The machine, roughly the size of a refrigerator, sat in the family’s living room connected by a telephone line to the university. In an era when most people had never seen a computer, Wilkes was pioneering what would eventually become known as remote work.

The Dismissal of Foundational Work

Despite her revolutionary contributions, Wilkes’s work was consistently characterised as “support” rather than fundamental innovation. This reflected broader patterns of gender discrimination in early computing, where women’s technical contributions were systematically undervalued. The irony is particularly stark given that Wilkes’s user-centred approach to computing—her focus on making machines accessible to individual users rather than requiring specialised operators—became the defining characteristic of personal computing.

Her LAP6 operating system embodied principles now recognised as central to user-centred design. It provided a uniform command set that users could augment, featured an intuitive text editing system that allowed users to work “as though working directly on an elastic scroll,” and prioritised reliability and user control. These innovations directly influenced the development of modern interactive computing interfaces.

The Return to Law

After eleven years in computing, Wilkes made another dramatic career transition. In 1972, she enrolled at Harvard Law School, finally pursuing her original dream. She graduated and became a practising attorney in 1975, building a distinguished legal career that spanned over 35 years. She served as head of the Economic Crime and Consumer Protection Division of the Middlesex County District Attorney’s Office, taught in Harvard Law School’s Trial Advocacy Program, and became an arbitrator for the American Arbitration Association, specialising in cases involving computer science and information technology.

Recognition at Last

Modern computing historians increasingly recognise Wilkes’s pioneering role. Her work has been featured in exhibitions at Great Britain’s National Museum of Computing and Germany’s Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum. In 2015, the Heinz Nixdorf Museum opened an exhibition honouring women in computing, recognising Wilkes alongside pioneers like Ada Lovelace. A colleague from Washington University, attending the opening, recalled: “Mary Allen gave a short speech in German. What a tour de force!”

The Lasting Legacy

Mary Allen Wilkes’s story illuminates both the possibilities and the prejudices of early computing. She helped create the conceptual and technical foundations of personal computing—the idea that individuals could directly control powerful machines, that computers could be user-friendly, and that computing could happen anywhere, including at home. Yet because her work was classified as “support,” her contributions were largely overlooked.

Today, as we reckon with ongoing gender disparities in technology—where women comprise only 16% of the UK’s technology workforce—Wilkes’s story serves as both inspiration and warning. Her career demonstrates that women have been central to computing’s development from its earliest days, despite being systematically written out of its history. Understanding figures like Wilkes isn’t merely about historical accuracy; it’s about recognising the full scope of human innovation and ensuring that future technological development benefits from diverse perspectives.

Mary Allen Wilkes proved that a geography teacher’s prediction could change the world. Her legacy reminds us that the most transformative innovations often come from those whose contributions are initially dismissed as mere “support.”

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment