3rd June 1781, Louisa County, Virginia

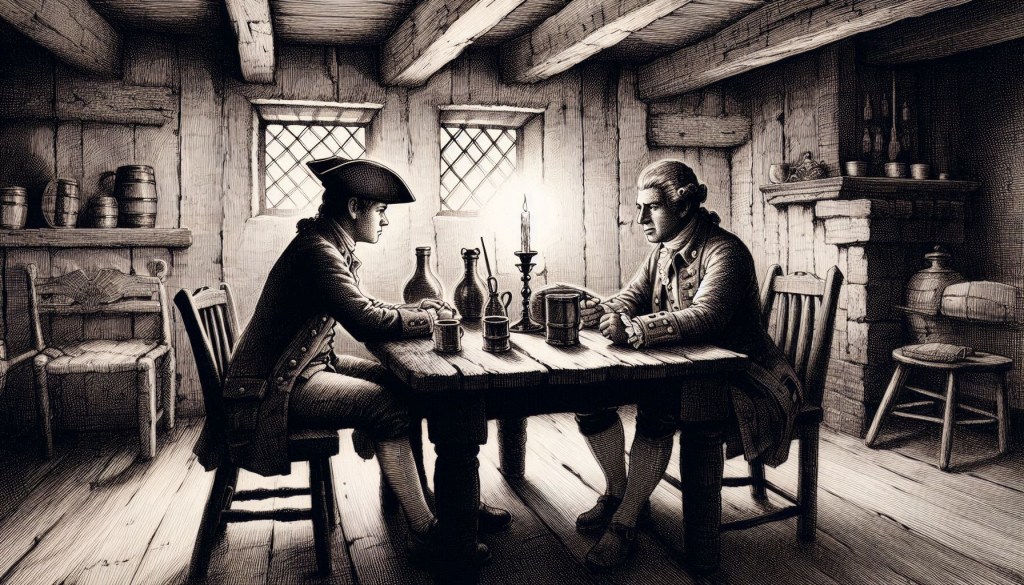

The amber glow of candlelight danced across the weathered oak tables of the Cuckoo Tavern, casting long shadows that seemed to whisper of the Revolution’s uncertainty. I shifted my weight carefully, favouring my good leg whilst cradling the pewter tankard of cider that had grown warm in my hands. The tavern hummed with the low murmur of conversation—farmers discussing crops, militiamen sharing news from distant counties, and the occasional merchant lamenting the war’s toll on commerce.

My name is Elijah Green, and at nineteen, I’ve already seen more of Virginia’s backwoods and British sabres than most men twice my age. The musket ball that had found my thigh three weeks prior near Charlottesville had earned me these days of enforced rest, though my mind remained as restless as ever. In my saddlebags upstairs lay three books—the only possessions of true value I carried beyond my rifle and the dispatches that were my livelihood.

The tavern door swung open with a groan of ancient hinges, admitting a figure whose very presence seemed to command the room’s attention. Jack Jouett stepped inside, his tall frame filling the doorway, his eyes scanning the assembled company with the practiced wariness of a man who lived between worlds—patriot and scout, gentleman and warrior. His riding boots bore the dust of hard miles, and there was something in his bearing that spoke of urgency barely contained.

He settled at the table beside mine, and I couldn’t help but study him in the flickering light. Here was a man whose reputation preceded him—a planter’s son who’d chosen the dangerous life of a militia officer and courier, carrying intelligence through enemy lines with the same casual efficiency other men might employ to tend their tobacco fields.

“You heard the commotion up the road?” I said, breaking the comfortable silence that had settled between us. “Rider said he saw redcoats near Louisa. Cavalry, not regulars—fast.”

Jouett’s eyes narrowed, and I saw his fingers tighten imperceptibly around his own tankard. “Cavalry? That’d be Tarleton. Devil rides hard when he smells prey.”

The name sent a chill through me that had nothing to do with the evening air. Banastre Tarleton—”Bloody Ban” to those who’d felt the edge of his sabre or witnessed the aftermath of his victories. I’d seen the ruins his dragoons left in their wake, the burned farms and the hollow-eyed survivors who spoke his name in whispers.

“If he’s headin’ west,” I said, allowing myself a grim smile, “there’s only one prey worth the trouble—Richmond’s gone quiet. But Monticello? That’s a prize.”

The realisation struck Jouett like a physical blow. I watched his face transform, the casual alertness giving way to something harder, more urgent. “Jefferson and the Assembly… If they’re caught, it’s over. No time for generals or letters now. I ride.”

“At night?” I asked, alarmed despite myself. “Through the woods?”

He was already pushing back his chair, reaching for his coat with movements sharp and decisive. “There’s no choice. The Revolution doesn’t wait for daylight.”

As he prepared to leave, something compelled me to speak—perhaps it was the books in my saddlebags, or the weight of words unspoken that had accumulated during my convalescence. “Jouett,” I called softly. “If you don’t mind my asking—what drives a man to ride forty miles through enemy territory in the dark? What makes such a risk seem reasonable?”

He paused, one arm already through his coat sleeve, and for a moment the urgency left his features. “You’re a reading man, aren’t you, Green? I’ve seen you with books.”

I nodded, surprised he’d noticed.

“Three books changed how I see this war,” he said, settling back down for just a moment. “First was Plutarch’s Lives—my father made me read it when I was your age. Those ancient Romans and Greeks, they understood something about duty and sacrifice that we’ve nearly forgotten. When Cato chose death over submission to Caesar, when Cincinnatus left his plough to save Rome—that’s what shapes a man’s character.”

The tavern seemed to grow quieter around us, as if the very walls were listening.

“Second was Common Sense,” he continued. “Paine’s words cut through all the genteel debate about reconciliation and showed us what we really faced—tyranny or freedom, with no comfortable middle ground. Made it clear that some fights can’t be avoided, only won or lost.”

“And the third?” I prompted, genuinely curious now.

“The Bible,” he said simply. “Specifically, the Book of Nehemiah. A man who rebuilt Jerusalem’s walls whilst his enemies plotted against him. He worked with a tool in one hand and a weapon in the other, because the work was too important to stop, even when surrounded by danger.”

I thought of my own three books—the worn copy of Robinson Crusoe that had fired my imagination as a boy, teaching me that resourcefulness and persistence could overcome any trial; the volume of Shakespeare’s histories that had shown me how power and politics played out across generations; and my own well-thumbed Bible, inherited from my grandfather, which had given me the moral framework to understand why this war mattered beyond mere politics.

“You see,” Jouett said, standing again and adjusting his coat, “those books taught me that some moments demand everything of a man. This is one of those moments. If Jefferson falls, if the Assembly is captured, then all our words about liberty become meaningless. Sometimes the only way to preserve the idea is to risk everything for it.”

He moved towards the door, then turned back one final time. “Keep reading, Green. When this war is over, we’ll need men who understand both action and reflection. The country we’re building will need both swords and scholars.”

The door closed behind him with a finality that seemed to echo through the tavern. I listened to the sound of his horse’s hooves receding into the night, carrying him towards whatever fate awaited at Monticello. Around me, the other patrons resumed their conversations, unaware that they had just witnessed the departure of a man riding not just to warn Jefferson, but to preserve the very possibility of the future we all hoped to build.

I finished my cider and climbed the stairs to my room, thinking about books and the men who let them shape their choices. In a few hours, dawn would break over a Virginia that might be forever changed by one man’s midnight ride through enemy territory. The Revolution, as Jouett had said, would not wait for daylight.

The End

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to Bob Lynn Cancel reply