Write about your dream home.

Monday, 11th February 1867

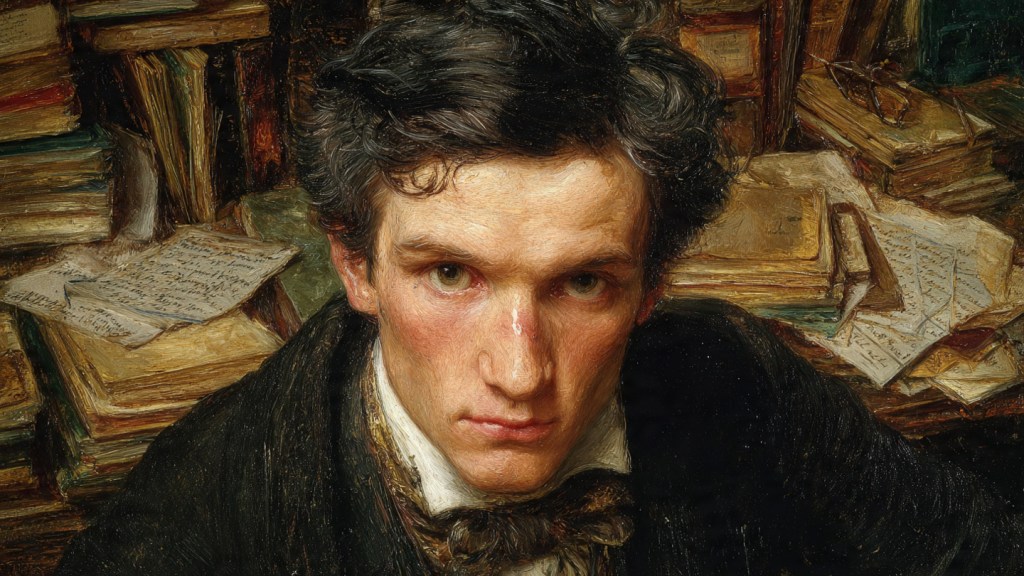

You will forgive the bluntness of what follows, if you have any charity left for a man whose tongue has been rasped raw by too much smoke and too many lies. I have spent the day amongst papers and persons that ought never to meet: the clean, smug print of statutes and circulars, and the unclean, shivering flesh that those statutes contrive to overlook. It is a strange thing, to live in a city that can number its dead in columns and yet mislay a living child as easily as a clerk drops a blot of ink.

I write as one speaks in a fever – because I have, in truth, something of a fever, or at least that restless heat that comes when the blood will not settle. My hands tremble at times, not with fear (I have seen enough to make fear a stale companion), but with the sort of inward vexation that makes one’s pulse a rebuke. There is a tightness across my chest, as though the fog itself has taken lodgings in my lungs, and I cough with an obstinacy that makes the landlady’s stair-rail rattle beneath my grip when I climb. A man may grow used to hunger; he does not grow used to a body that argues with him at every step.

You may ask why I do not rest, why I do not take a draught, or keep to my rooms, or do as sensible men do – eat, sleep, and hold my peace until the world improves of its own accord. Because I have tried it, and it is a species of death. There is a kind of quiet that is only cowardice with a clean collar. When the wrong is done within a mile of you, and you keep your chair, your chair becomes a dock, and you sit there as your own judge.

Yet I am no saint, if that is what you are turning me into, for the comfort of hating me later. My fault is a plain one: I am too quick. I see an injury, and I strike at it as a dog snaps at a stick – before I have looked to see who holds it, or how many more sticks wait in the dark. There is a moment – always a moment – when I might choose prudence, and in that moment my whole frame seems to surge forward of its own will, as if my conscience were a hand at my back. Afterwards comes the reckoning: the magistrate’s lifted brow, the constable’s grin, the printed warning, the lost employment, the closed door.

This morning, for example, I had no business in the Police Court. I told myself I went only to listen, to observe, to take notes as a scholar might – dispassionate, careful, fit for citation. That was the lie that got me out of bed and into the street. The truth is, I went because I had heard a thing of a parish matter – an “irregularity”, they call it, as though a starving man were but a smudge in an account-book – and I could not bear to sit with the knowledge as one sits with an undelivered letter.

The court was full of the usual odours: damp wool, cheap gin, the faint sour of unwashed linen, and that peculiar smell of public rooms where the poor are made to stand still. A woman stood there, not old, but worn into the likeness of age, with a shawl that did not keep out the draught. She was not charged with any fine villainy; her offence was want, made visible. The question was put to her as one puts a question to a servant: where she belonged, what parish had claim upon her, where the child’s father had gone, whether she had “character”. Character! As if character were a loaf a woman might buy when wages fail.

I watched the clerk’s pen scratch, and I felt my jaw set. It is always the pen that does it to me. A pen can turn a life into a line; it can deny a belly its bread; it can send a man to the treadmill or to the stones; it can separate mother from child with an elegant flourish. And we praise ourselves for being a nation of law, as if law were the same as justice. The law is a fine coat, often; justice is the warmth beneath it, and we have grown fond of the coat and careless of the cold.

The constable behind her shifted his weight, bored, as though he had been posted there to mind a parcel. The child – little more than a bundle with eyes – began to whimper, the way a kettle begins to sing before it boils. The magistrate frowned, not in sympathy, but in irritation, and asked for silence. Silence! The child’s throat was the only honest instrument in the room, and they would have it stopped.

I do not know at what point I ceased to be an observer and became – what shall we call it? – a nuisance. I spoke. I spoke too soon, too loudly, and with too much contempt in it. I said, in effect, that it was a monstrous thing to demand “character” as the price of bread, that a parish ought not to shuffle its obligations like a pack of cards, that a child’s hunger is not made less urgent by a legal quibble. I said more than I should; I said it with that sharp relish that bitterness lends to the tongue, and I saw heads turn, not toward the injustice, but toward the impertinence.

Of course they warned me. Of course they threatened to have me removed. Of course I tasted, for a moment, the humiliating possibility of being treated as one of the very vagrants whose defence had made me speak. And there it is – my absurdity laid bare. I cannot bear to see a stranger wronged; I can barely bear to see myself slighted. My pride and my pity are too near of kin.

You might think such a scene would shame me into caution. It has not. It has only soured my view further of those who congratulate themselves upon order. What is their order? A set of clean pavements in the West, and in the East a river of mud where men are expected to drown decently, without splashing the boots of their betters. We have charitable committees, and subscriptions, and sermons that ring like coins upon a plate; we have inspectors, and boards, and guardians; we have phrases enough to paper the walls of every lodging-house in Whitechapel. And still the same small tyrannies repeat, as regular as the striking of a clock.

All day, too, one hears talk of Reform. It floats through coffee-rooms and lecture-halls like the scent of roasting meat – inviting to those already well-fed, tormenting to those who stand outside. The gentlemen debate, the newspapers thunder, and each man professes himself the truest friend of the working classes, provided always that the working classes remain grateful, docile, and at a suitable distance. They speak of the constitution as if it were a holy relic; they speak of the people as if they were a tide to be managed with sandbags. If justice is to be done, it must be done with a thousand cautions, so that no one of consequence need feel the least inconvenience in the doing of it.

Do you know what makes me most cynical? It is not that wicked men exist. I have never expected virtue to be universal. It is that decent men will look at a wrong, admit it is a wrong, and then – because to mend it would disturb some arrangement – will propose instead a sermon, a committee, a delay. They will stand about a suffering person as men stand about a fire, warming their hands on the idea of compassion, and leaving the burning to continue.

And still, for all this bile I am pouring out, I cannot pretend that I have ceased to believe in justice. If I had ceased, I should be at peace, and peace is precisely what I cannot attain. Justice is my vice as much as my virtue; it is the spur in my side. It makes me stupidly honest. It makes me refuse the small bargains by which a clever man secures his future. It makes me write letters that ought never to be written, and speak words that ought, for my comfort, to remain unspoken.

This afternoon I attempted to work – proper work, with books open and notes arranged, as though thought were a tame creature that comes when called. My eyes ran over the lines and would not take them in. There was a ringing in my ears, like distant wheels on stones. I had eaten nothing but bread, and that badly, and I drank tea too strong for an empty stomach, and presently my hands shook so that I spilt the cup and scalded my thumb. The pain was clean and almost welcome; it proved I was still made of flesh, not merely of grievance.

I considered laudanum, as one considers a dark alley: with a kind of horror, and yet with a certain curiosity as to how swiftly it would end the struggle. I did not take it. I have seen too many men soothe themselves into ruin. Besides, my trouble is not one that a bottle cures. It is a trouble in the arrangement of the world, and though my body suffers it, my body did not invent it.

Now you will think me merely railing. Let me be plain. I have done harm by my haste. I have forfeited opportunities – real opportunities – to advance a cause by more cunning means. Only last month I was urged (politely, condescendingly) to soften a passage in an article, to omit a name, to avoid a certain accusation that could not be proved without dragging a dozen poor witnesses into the open. It would have been wise. It would have preserved the publisher’s nerve, and perhaps gained me a steadier footing. I refused; I published elsewhere; I spoke with heat; I won the satisfaction of a clean conscience and lost the chance of a wider hearing. That is the pattern of my life, and if you are prudent you will despise it.

Yet I cannot wholly regret it. If a man trims his language until it will offend nobody, he has trimmed away the very edge by which truth cuts through complacency. The world is thick-skinned. It takes a sharp blade to make it feel.

You may wonder, then, what becomes of a man who is too just for comfort and too impulsive for success. He becomes tired. He becomes bitter. He begins to look upon every polite face as a mask. He hears, in every expression of sympathy, the faint clink of self-congratulation. He begins to suspect that the great engine of society is built to turn suffering into a kind of fuel – quietly gathered, neatly stored, and never spoken of above a certain volume.

And because I am, for all my noise, a scholar – trained to make something of words – I am sometimes asked to set tasks for my pupils. This evening, one of them, a boy with clean nails and a careless smile, pressed upon me a theme his mother had proposed for his improvement: “Write about your dream home.”

There is your anachronism, if you like – your modern phrase dropped into my grimy palm. But I understand it well enough, for Victorians also dream; we only dress our dreams in more respectable clothing. Very well, then. Let me write of my dream home, since you ask, and since the very thought of it sets my teeth on edge.

My dream home is not a great house, though I have stood before such houses and admired the workmanship of their stone, while cursing the uses to which men put them. It is not a mansion with a porter and a carriage, nor a villa with a conservatory and a pianoforte. Those are not homes, in the true sense; they are fortresses built against the knowledge of other people’s hunger. A home that must be defended from the poor is already morally burglarised.

My dream home is first of all clean. Not “clean” in the priggish sense of spotless brass and scoured steps for the sake of appearances, but clean as in wholesome: dry walls, sound boards, air that does not rot the lungs. It has a fire that burns without making the eyes smart, and a window that opens without admitting a whole parish of soot. There is food that does not require a lie to obtain it, and a bed where sleep comes without the dread of tomorrow’s knock at the door.

In that home, the law is not a cudgel. It does not peer into a woman’s face to price her “character”. It does not hunt a man from parish to parish as though he were a stray dog, snapping at his heels with forms and seals. It does not take a child by the hand and lead him away, because a clause has been interpreted in a certain fashion. In my dream home, a magistrate would blush to speak of “order” while injustice sat at his elbow like a familiar.

In that home, a man may be poor and still be treated as a man. He may fail without being branded. He may ask for help without being forced to abase himself, as though bread were a favour and not a duty of a Christian society. Yes, I said “duty”. You may mock it; the fashionable minds prefer to speak of “economy” and “principle” as though those were higher than mercy. But if there is no duty to the weak, then all our talk of civilisation is merely the boasting of well-fed animals.

And there is one more feature of my dream home, which perhaps will make you laugh, for it is so small and yet so rare: in that home, I possess self-command. I can see a wrong and choose my moment. I can hold my tongue until it will do the most good, not merely until it will do the most to relieve my own indignation. I can act with steadiness, not with spasms. I can be just without being rash, and fervent without being foolish.

Do you see how the dream condemns me? The very home I long for is built partly of what I lack. I can describe it; I cannot inhabit it. Not yet.

When I set down my pen after writing those lines for the boy – when I imagined him copying them in his neat hand, with no notion of what they cost – I felt that old bitterness rise again. What right have I to speak of duty, when my own duty begins with governing myself, and I so often fail? What right have I to demand fairness from institutions, when my own impulses are a little private tyranny, driving me where they will? A man who cannot rule his temper will not easily reform a parish.

And still – still – I cannot make peace with injustice by scolding my own shortcomings. The wrong does not become right because I am imperfect. The child’s hunger does not abate because I spoke too sharply. The bruised woman does not heal because I lacked tact. If my haste ruins me, it will not ruin the cause. There are others – quieter, wiser, steadier – who may carry the thing forward. I only pray I do not, in my reckless zeal, give ammunition to those who would call all reform a species of disorder.

Tonight my body feels like a worn instrument: strings too tight, wood too thin, every sound a little too sharp. I have a headache behind the eyes, and a dryness in the throat that tea will not mend. My coat smells of damp and of other men’s rooms. I can hear, through the wall, the ordinary life of this house: someone moving a chair, someone coughing, the faint clatter of a plate. These small domestic noises would be comforting, if I did not know how swiftly comfort can be taken away by rent, by illness, by the whim of a man with authority.

If you are listening – if you are there at all, beyond this paper – do not mistake my cynicism for surrender. Cynicism is only wounded hope that has learnt to sneer. I sneer because I have hoped; I am bitter because I have believed that men might be better than they are. And I remain, in spite of myself, committed to the plain notion that justice is not an ornament for speeches but a bread for daily use.

Only – if you should ever find yourself about to do a righteous thing in a righteous heat, remember me. Remember that justice, if it is to endure, must be as patient as it is fierce. I have been fierce enough for two men, and patient for none. That is my confession, such as it is. Not for absolution. For accuracy.

Now I shall bank the fire, if it deserves that name, and attempt sleep. In the morning there will be more papers, more speeches, more tidy evasions. And if I am wise, I shall keep my counsel until counsel can bite. If I am myself, I shall see the first wrong and leap at it like a man possessed.

Bob Lynn | © 2026 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment