I: Before Dawn

The charcoal stick snapped in my frozen fingers, a sharp crack that sounded obscenely loud in the silence of the waiting.

I cursed under my breath, staring at the ruined sketch in my notebook. It was meant to be Sergeant Hospodar, leaning against the frozen railway sleeper, but the cold had turned my lines into jagged, shivering spasms. It didn’t look like a man; it looked like a ghost already fading into the grain of the paper.

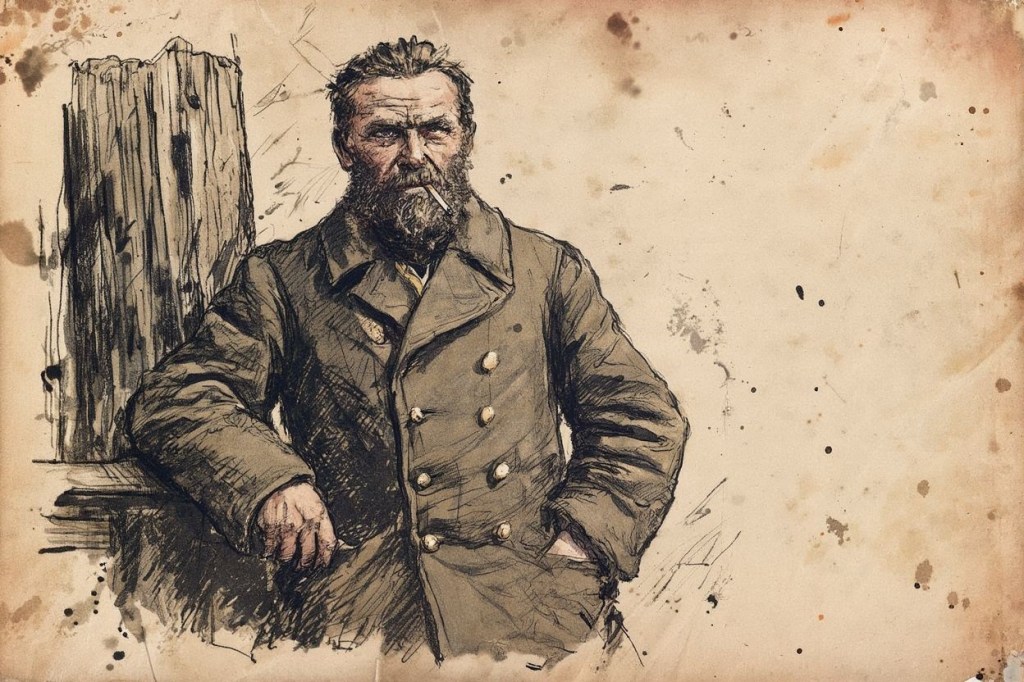

“Save the lead, lad,” Hospodar rumbled, not opening his eyes. He was huddled in his greatcoat, a mountain of grey wool and pragmatic fatalism. “You’ll need steady hands for the rifle soon enough.”

It was the twenty-ninth of January, 1918. We were dug into the hard, unforgiving earth of the embankment near Kruty railway station, one hundred and thirty kilometres northeast of Kyiv. There were perhaps four hundred of us – students from Saint Volodymyr University, cadets from the Khmelnytsky Military School, and a handful of Free Cossacks. Boys, mostly. I was eighteen, and I had never fired a weapon in anger.

The wind howled across the Chernihiv plains, carrying needles of ice that stung exposed skin. It was a brutal, biting cold that settled deep in the marrow, making the very idea of warmth feel like a memory from a different life. Beside me, Oleksandr, a philosophy student who had joined the Student Company only three days prior, was weeping silently. The tears froze on his cheeks.

“Check your bolt again, Mykola,” Hospodar murmured, shifting his weight. The old sailor had the uncanny ability to sleep with one eye open, like a gull on a masthead. “And mind the sand. This damp gets into the mechanism like rot.”

I worked the bolt of my Mosin-Nagant. Clack-clack. The sound was reassuringly mechanical, a binary certainty in a world dissolving into chaos. We had forty rounds each. Forty pieces of copper-jacketed death to hold back an army of four thousand Bolsheviks.

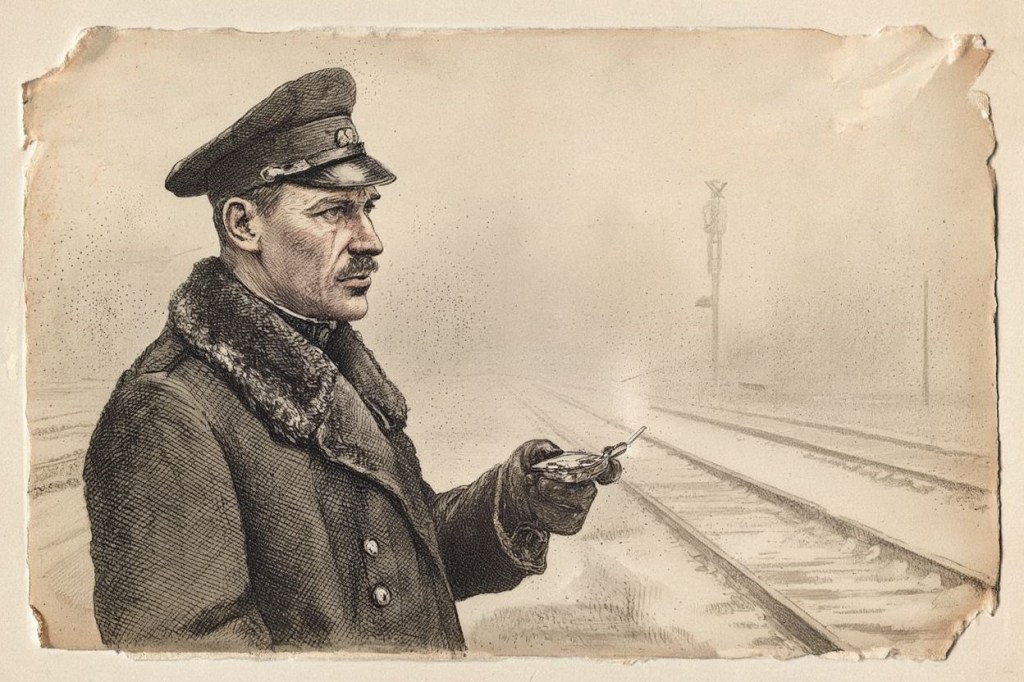

Around 05:00, the darkness seemed to thicken. The silence of the steppe was heavy, pressing against our eardrums. It was in this suffocating quiet that Captain Petro Omelchenko appeared.

He moved along the line like a shadow, stopping to adjust a machine gun placement or murmur a word to a shivering cadet. He was barely thirty, but in the predawn gloom, he looked ancient. His face was drawn, the skin tight over his cheekbones, his eyes burning with a terrible, lucid exhaustion. He knew what was coming. We all suspected, but he knew.

He stopped beside my position. I scrambled to stand, but he waved me down with a gloved hand. He crouched beside me, staring out into the black void where the tracks vanished towards Bakhmach.

“At ease, Cadet,” he said softly. His voice was cultured, precise – the voice of the lecture halls we had abandoned for trenches. He looked at my notebook, lying open in the snow. “An artist?”

“I try, sir. Just sketches.”

He nodded, but didn’t look at the drawing. He kept his eyes on the horizon. “It helps to focus the mind. To fix it on something small.”

He took a silver cigarette case from his pocket, opened it, saw it was empty, and closed it again with a sharp snap. He didn’t seem disappointed, merely resigned.

“Tell me, Mykola,” he said, and the shift in his tone caught me off guard. It was conversational, almost casual, as if we were sitting in a café on Khreshchatyk Street rather than waiting to die in a snowdrift. “In the life before this… what were your favourite sports? To watch, or to play?”

I stared at him, bewildered. The question hung in the freezing air, absurd and surreal. Sports? When the Red Guard was marching to hang us from the station rafters?

“Sir?”

“Humour me,” he whispered, his breath clouding in the grey air. “I need to remember that there are other things in the world besides ammunition counts and railway timetables.”

I swallowed, my throat dry despite the cold. I thought of Kyiv in the summer. The smell of dust and linden trees.

“Football, sir,” I stammered. “I played half-back for the school team. And I… I enjoyed watching the sculling races on the Dnieper. The rhythm of it.”

Omelchenko nodded slowly, a ghost of a smile touching his cracked lips. “Football. Chaos controlled by rules. A game of territory.” He shifted his gaze to me. “And chess?”

“I play a little. My father taught me.”

“Chess is better,” Omelchenko murmured, more to himself than to me. “In chess, the pawns don’t bleed. You sacrifice a piece to gain a tempo, to control the centre. It is clean. Mathematical.”

He looked back towards the railway station, a dark skeleton against the lightening sky.

“That is what we are doing here, Mykola. It is a game of tempo. We are not the queens or the rooks. We are the pawns thrown forward to block the file. To buy time for the King to castle.” He turned his collar up against the wind. “But the tragedy of war, unlike chess, is that the pawns feel the cold. And they have mothers.”

The metaphor settled over me, heavy and suffocating. The “game” he spoke of wasn’t metaphorical to him; it was a tactical reality. We were the delay. The sacrifice.

“Do we have a chance, sir?” I asked, the boy in me breaking through the soldier’s veneer.

Omelchenko looked at me, and for a moment, the mask of command slipped. I saw a profound, aching sadness. “In the game of history? Yes. We buy a day. Maybe two. That time allows the diplomats in Brest to sign a treaty. It allows Ukraine to exist on paper, if not in flesh. That is the victory.” He gripped my shoulder, his glove rough against my coat. “But in the game of flesh… keep your head down, Mykola. Fire only when you have a target. Do not spend your life cheaply.”

He stood up, the moment of intimacy snapping shut as quickly as his cigarette case. “Sergeant Hospodar?”

“Sir,” the old sailor grunted, shifting to attention.

“They will come with the sun. Watch the tree line to the east. Muravyov likes his theatrics. He will likely march them in columns, expecting us to run.”

“Let them come,” Hospodar spat into the snow. “I have something for them.”

Omelchenko moved on down the line, a solitary figure disappearing into the mist. I looked down at my hands. They were trembling, not just from the cold now.

Sports. Football matches played on muddy fields where the worst injury was a bruised shin. Rowing races where the only enemy was exhaustion. Innocent games. I realised then that my childhood hadn’t ended when I put on this uniform; it had ended just now, with a question about games asked by a man who knew the score was already settled.

“He’s a good man,” Hospodar muttered, breaking the silence. “Too thinking for a soldier, but a good man.”

“He thinks we’re going to die,” I whispered.

Hospodar didn’t answer immediately. He pulled a rag from his pocket and wiped the condensation from his rifle sight.

“We’re all going to die, lad. Today, tomorrow, fifty years from now in a feather bed.” He looked at me, his eyes hard as flint. “The only choice you have is how you play the hand you’re dealt. That’s the only sport that matters now.”

The sky began to bleed into a bruised purple in the east. The dawn was coming. And with it, a low, rhythmic thrumming began to vibrate through the frozen ground – not the sound of a game, but the heavy, mechanical tread of four thousand pairs of boots.

“Here we go,” Hospodar said softly. “Kick-off.”

II: The Assault

The first shell didn’t scream; it sighed.

It was a strange, mournful whistle that dropped out of the grey sky and punched a crater of black earth into the snow fifty yards ahead of our line. Then came the roar – a concussive crump that rattled my teeth and sent a spray of frozen mud pattering against my helmet like hail.

“Artillery!” someone screamed – Oleksandr, I think – his voice cracking high and thin.

“Steady!” Sergeant Hospodar’s voice was a granite anchor in the rising storm. “It’s ranging fire. They’re blind as bats in this mist. Keep your heads down!”

I pressed my face into the dirt of the embankment. The smell of wet wool, cordite, and raw terror filled my nose. My heart was hammering against my ribs, a frantic, trapped bird. This is it, I thought. The whistle has blown.

For twenty minutes, the Bolshevik guns chewed up the field in front of us. It was terrifying but sloppy; they were firing at map coordinates, not targets. But then the shelling stopped as abruptly as it had begun, leaving a ringing silence that was somehow worse.

“Eyes front!” Captain Omelchenko’s voice cut through the ringing. He was standing upright, scanning the tree line with field glasses, disregarding the shrapnel singing through the air. “Here they come.”

I peeked over the rim of the trench.

They emerged from the birch woods like a dark stain spreading across a white tablecloth. Hundreds of them. No, thousands. They weren’t running or crouching; they were walking. Marching. Shoulder to shoulder in dark greatcoats, rifles at port arms, a forest of bayonets glinting dully in the weak winter sun. It was grotesque – a parade-ground formation moving into the teeth of machine guns. It was the arrogance of empire; they didn’t think we were worth the indignity of tactical movement. They thought they could simply walk over us.

“Hold…” Omelchenko called out, his voice calm, almost instructional. “Wait for the mark. Wait until you can see their faces.”

The distance closed. Five hundred yards. Four hundred. I could hear them now – the crunch of boots on snow, the jingle of kit. A low murmur of voices. They were singing. Singing. A revolutionary hymn, swelling like a dark tide.

My rifle barrel wavered. I braced it against a frozen root, trying to remember the drills. Sight picture. Breath. Squeeze. It felt ridiculous, like bringing a needle to a knife fight.

“Steady, lads,” Hospodar murmured beside me. He had a cigarette unlit in the corner of his mouth. “Let them come to the party.”

Three hundred yards.

“Now!” Omelchenko roared. “Fire!”

The embankment erupted.

The Maxim guns on our flanks opened up with a sound like canvas tearing – a continuous, stuttering brrr-rrr-rrr-rrr. My own rifle kicked against my shoulder, a solid, bruising punch.

Downrange, the parade disintegrated.

The front rank of the Bolshevik column simply vanished. Men folded, crumpled, and pitched forward as if invisible wires had been cut. The singing stopped, replaced by a collective scream that rose over the mechanical chatter of the guns. The dark stain shattered into chaotic fragments.

“Got you!” Oleksandr yelled, working his bolt frantically. “I got one!”

“Reload and fire! Don’t watch!” Hospodar barked, cuffing him on the helmet. “This isn’t a spectator sport!”

I fired, bolted, fired again. I didn’t aim at men; I aimed at shapes. It was mechanical, dissociative. The “game” Omelchenko had spoken of was suddenly horrifyingly literal – it was a contest of geometry and physics. We had the angle; they had the mass.

But mass has a quality of its own.

For an hour, we held them. The snow in front of the embankment turned black, then red. Bodies piled up in windrows. But they didn’t stop. They stopped marching and started fighting. They spread out, using the dead for cover, crawling forward, working their way towards our flanks. The “parade” became a hunt.

“Ammo!” a voice screamed from the left. “Machine gun two is dry!”

“Run a belt over!” Omelchenko ordered, pointing to a cadet runner. The boy scrambled up, clutching an ammunition box, and a split second later, his head snapped back in a spray of pink mist. He dropped like a sack of grain.

I stared, my hands freezing on my rifle. That was Hryts. I had shared tea with him yesterday. He owed me a cigarette.

“Mykola! Fire!” Hospodar’s shout broke my paralysis.

I fired. Click.

“Dry!” I gasped, fumbling for a stripper clip with numb fingers. The metal was sticky with cold. I shoved the rounds in, jamming my thumb, not feeling the pain.

The volume of fire from our line was thinning. The relentless thud-thud-thud of the Maxims was becoming sporadic. We were running out of pieces to play.

“They’re flanking right!” someone shouted.

I looked. To the east, where the railway embankment curved, dark shapes were moving fast, leapfrogging through the scrub brush. They were trying to turn our line.

“Captain!” I yelled, turning to look for Omelchenko.

I saw him standing near the command post, directing the fire of the last operational Maxim. Then I saw him jerk. It wasn’t dramatic, like in the plays. He just spun half-around, as if someone had tapped him on the shoulder, and sat down heavily in the snow.

“Captain!”

I started to rise, but Hospodar grabbed my ankle. “Stay down, you fool! You can’t help him!”

“He’s hit!”

“We’re all going to be hit if that flank collapses!” Hospodar roared, his face streaked with soot and sweat. “Eyes front!”

But the rhythm had broken. You could feel it – the momentum of the game shifting violently against us. The sheer weight of the Bolshevik numbers was pressing us down. We were a dam cracking under the weight of an ocean.

Then came the final blow. A runner – a cadet from the reserve platoon – came sliding into our trench, his eyes wide with panic.

“The Shevchenko Regiment!” he gasped, grabbing Hospodar’s coat. “They’re at Nizhyn!”

“Thank God,” I breathed. “Reinforcements.”

The runner shook his head frantically, tears cutting tracks through the grime on his face. “No. No! They’ve turned! They’re with the Reds! They’re firing on the train!”

The words hit me harder than the artillery. Betrayal. The board had been kicked over. The pieces we thought were ours were suddenly enemy knights.

Hospodar went still. He looked at the runner, then out at the advancing grey wave, then back at me. The cigarette fell from his mouth.

“That’s it, then,” he said quietly. “Game over.”

He turned towards the command post where Omelchenko was being dragged into cover by two medics. The Captain’s face was grey, his tunic dark with blood, but he was waving them off, trying to point towards the rear.

Withdraw. The order rippled down the line, not a shout but a desperate whisper. Pull back to the train. Pull back.

It wasn’t a retreat; it was a collapse. Men scrambled out of foxholes, slipping on the icy mud. The discipline of the morning evaporated into the primal instinct to survive.

“Move, Mykola! Move!” Hospodar shoved me towards the slope.

I scrambled up, boots slipping. I looked back one last time. The field was a charnel house. The snow was ruined. And in the distance, through the smoke, I saw the Bolsheviks rising from the ground, bayonets leveled, howling their victory.

I ran. I ran past the bodies of boys I knew. I ran past the abandoned Maxim gun, its barrel smoking in the cold air. I ran with the shame of the living, my breath tearing at my lungs like broken glass.

What games do you play? Omelchenko’s voice echoed in my head, mocking me.

I play the one where I run away, I thought bitterly. I play the one where I live.

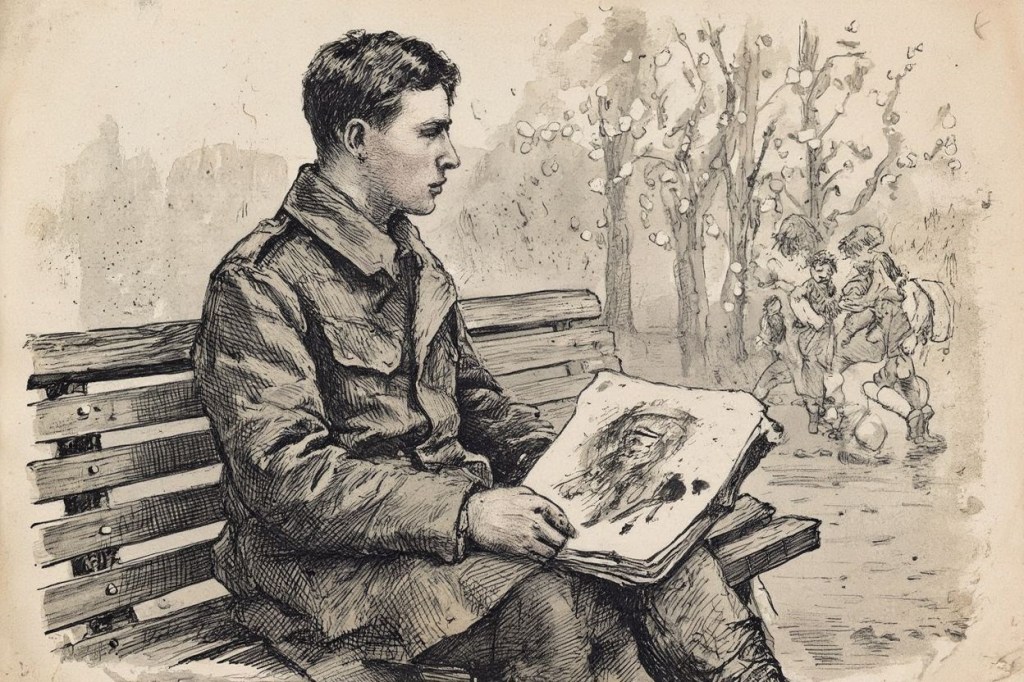

III: After the Field

The silence of Nizhyn was different from the silence of the waiting. It wasn’t empty; it was heavy, filled with the things we didn’t say.

We were gathered in a requisitioned schoolhouse, three days after the battle. The air smelled of iodine, wet wool, and unwashed bodies. Survivors sat on benches or lay on straw pallets, staring at nothing. Every time a door slammed, half of us jumped.

I sat in a corner, my notebook open on my knees. My hands were finally steady enough to hold the charcoal, but I wasn’t drawing. I was just staring at the blank page, waiting for an image that wouldn’t terrify me.

“Eat,” a voice rumbled.

Sergeant Hospodar dropped a tin cup of weak tea and a piece of black bread onto the bench beside me. He looked older now. The granite of his face had cracked, revealing something tired and brittle underneath. His left arm was in a sling, the result of a fall during the retreat to the train.

“I’m not hungry, Sergeant.”

“Didn’t ask if you were hungry. Said eat.” He sat down heavily, wincing. “Fuel the engine, lad. We have a long walk to Kyiv.”

I picked up the bread. It tasted like ash.

“Have you heard about the Captain?” I asked, keeping my voice low.

Hospodar took a slow sip of his tea. ” died on the train. Just past Bobryk. Loss of blood.”

I nodded. I had known, really. I had seen the colour of his face when they carried him. But hearing it spoken aloud made it final. The man who had turned our slaughter into a game of chess was gone, swept off the board.

“And the others?” I asked. “Hryts? Oleksandr?”

“Oleksandr is over there,” Hospodar pointed with his chin to a figure curled in a ball against the wall, rocking slowly. “Hryts… Hryts stayed on the field.”

I closed my eyes. I could see the snow again. The black earth. The red stains.

“It was for nothing,” I whispered. The bitterness was a poisonous taste in my mouth. “We played their game. We died. And they’re still coming. The Shevchenko Regiment turned… the whole world is turning Red. We were just… road bumps.”

Hospodar set his cup down with a sharp clink. He turned to face me, and for a moment, the old fire was back in his eyes.

“Don’t you say that,” he growled. “Don’t you ever let me hear you say that.”

“But look at us!” I gestured around the room. “Look at this! We lost!”

“Did we?” Hospodar leaned in, his voice dropping to a conspiratorial rasp. “Word came down from the telegraph office an hour ago. From Brest-Litovsk.”

I looked at him, uncomprehending. Brest was a thousand miles away. A table with diplomats in frock coats. What did it have to do with us?

“They signed it,” Hospodar said. “The Central Powers. Germany, Austria. They signed the treaty with the Ukrainian People’s Republic. They recognised us. We are a nation, Mykola. Officially. On paper. In the eyes of the world.”

He sat back, a grim satisfaction settling over his features.

“They needed time. The delegation… they needed just a few more days to convince the Germans we still held the capital. To convince them we were worth betting on.” He tapped the table with a calloused finger. “We gave them those days. Us. At Kruty. We bought that treaty with forty rounds of ammunition and a lot of good blood.”

I stared at the bread in my hand. Tempo, Omelchenko had said. We sacrifice a piece to gain a tempo.

“So that was the game,” I murmured.

“That was the game,” Hospodar agreed. “And we won it. The Captain… he knew the rules. He played his hand.”

I opened my notebook again. I turned past the jagged, shivering sketches of the predawn wait. I found a clean page.

I began to draw. Not the horror. Not the bodies. I drew Captain Omelchenko as I remembered him in that quiet moment before the sun rose. Standing in the snow, cigarette case in hand, looking at the horizon with that sad, knowing smile. The man who knew he was a pawn, and played like a king.

Two Months Later – Kyiv, April 1918

The linden trees on Khreshchatyk were budding, a hazy green mist against the stone facades. The city was loud again – trams rattling, vendors shouting, the noise of life continuing with an almost insulting persistence. The Bolsheviks had come and gone, driven out by the German bayonets that our treaty had purchased.

I sat on a bench near the university, watching a group of children playing in the park. They were kicking a rag ball around, shouting and laughing, chasing each other in chaotic circles.

“Goal!” one of them screamed, throwing his arms up in victory.

I flinched. The sound was too sharp. Too sudden.

I watched them run. They played with such intensity, such absolute belief that the game was the only thing that mattered in the world. They didn’t see the bullet holes in the plaster of the opera house across the street. They didn’t see the fresh graves in the Askold’s Grave park.

I reached into my pocket and pulled out the small, battered notebook. The drawing of Omelchenko was smudged now, the charcoal fading, but the eyes were still sharp.

What are your favourite sports to watch and play?

I looked at the children. I watched the ball arc through the air, suspended for a moment against the blue sky – a perfect, parabolic curve of physics and grace.

“I like football,” I whispered to the empty air, answering him properly for the first time. “I like football because the rules are fair. Because when the whistle blows, everyone goes home.”

I stood up, putting the notebook away. The grief was still there, a heavy stone in my chest, but it had settled. It was part of the foundation now.

I walked towards the university gates. I had lectures to attend. I had a country to build. That was the new game. It was a harder one, a longer one, with no clear rules and no referee. But I owed it to Hryts. I owed it to Omelchenko.

I owed it to the pawns who had held the line so the rest of us could learn how to be players.

As I walked, a cheer went up from the park behind me. Another goal. Another victory.

I didn’t flinch this time. I just kept walking, one foot in front of the other, listening to the sound of the game continuing.

On 29th January 1918, approximately 500 Ukrainian cadets and students engaged 4,000 Bolshevik troops at the Battle of Kruty, 130 kilometres northeast of Kyiv. While the battle ended in a tactical defeat with over 50% of the Ukrainian force killed or captured, the delay allowed the Ukrainian People’s Republic to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 9th February, gaining international recognition and military support from the Central Powers. The twenty-seven students captured and executed by Bolshevik forces were later reburied at Askold’s Grave in Kyiv. In 2006, the Kruty Heroes Memorial opened on the site, and the event remains a central symbol of national identity in independent Ukraine.

Bob Lynn | © 2026 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment