Describe a man who has positively impacted your life.

Monday, 18th December, 1865

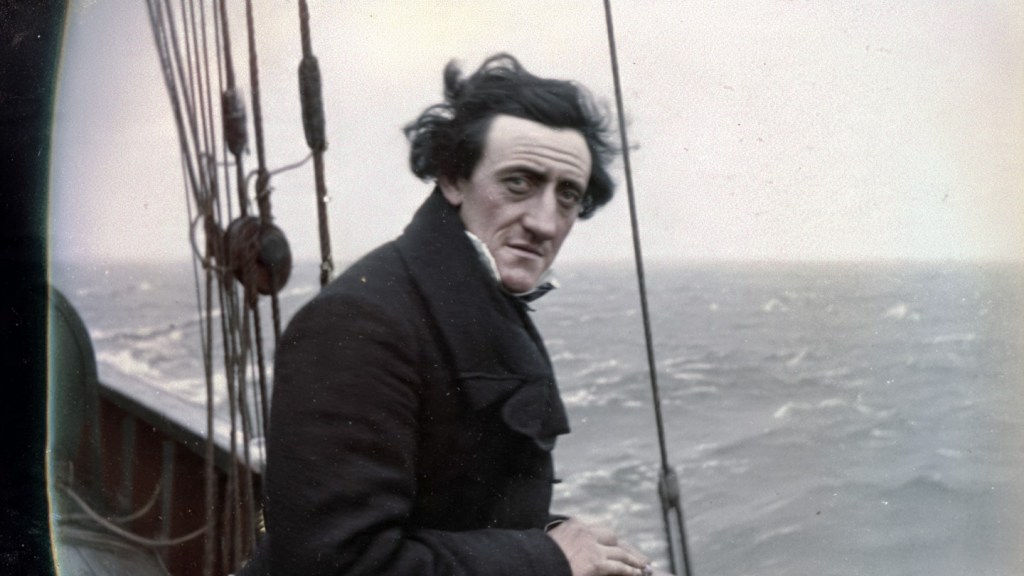

Aboard the mail-packet Euphrates, Bay of Biscay

You ask me why I smile – why, when the mourning-band is still upon my sleeve and the crêpe yet stiff with salt – I stand at this rail and call it justice done. Well, sir, I shall tell you plain, for I have no patience left for pretty evasions, and the sea makes a man blunt.

My brother is dead. Fever took him at Bombay three months since, and I have his effects in a locked chest below: his watch, his Bible, his commission, and a letter he never finished. I ought to weep. I ought to bow my head and speak of the Lord’s inscrutable will. Instead I feel the wild surge of vindication in my chest, hot as brandy, sharp as the December gale that rattles these shrouds. For the man who wronged him – who slandered his name, who drove him out to that pestilent posting with lies and malice – has been cashiered. Dismissed. Broken. The enquiry sat whilst I was yet outbound, and the verdict came by telegraph to Gibraltar. The truth won.

It was I who forced the matter. Oh, I see you mark that – yes, I pushed it forward, wrote the letters, demanded the hearing, spent money I had not got and called in debts I should have left sleeping. My wife begged me to let it lie. “He is gone,” she said, “and you will make enemies.” But I am not a man to let injustice fester. I never have been. I act, sir. I strike whilst the iron is hot, and devil take the consequences.

That is my nature, and it has served me ill more than once. There was a matter at school – a fight, a broken collarbone, my own expulsion narrowly avoided because my father knew the Head. There was the duel I nearly fought at two-and-twenty over a card-game insult, until a friend locked me in his rooms the night before and talked me cold. There was the business venture I plunged into without counsel, which cost me two years’ income and my father’s regard. Impetuous, they call it. Rash. My mother, God rest her, called it “hasty blood,” and said I had it from her side of the family – Cornish folk, who would sooner leap than look.

But this time – this time, by God, I was right. My brother’s honour has been restored. The record is amended. His widow will receive the pension, and his children will not grow up under a cloud. I have won.

And yet.

The wind cuts like a blade across this deck, and my hands upon the rail are raw. I think of home – of England – green and cold and mercifully small, where a man may know his neighbours and his duty, where the rain falls soft and the churchyard lies quiet under yew-trees. I have been gone eighteen months. I volunteered to go out and fetch my brother’s body back – they would have buried him at Bombay, you understand, in that crowded Christian cemetery by the docks, but I could not bear it. I thought: he shall lie in Somerset, beside our father, where he belongs. So I took passage, and I brought him home. Or rather, I brought his bones home, sealed in a lead coffin that weighs upon my conscience like a millstone.

I have not yet opened his last letter. It lies in my coat now, against my heart, growing warm with my body’s heat. I fear what it will say. I fear his forgiveness.

Do you know what wounds me most, sir? Not the fever. Not the squalor of that death – though I have seen the hospital, and it is a shameful place, rank with neglect. No. What wounds me is this: I quarrelled with him before he sailed. It was three years ago, in our father’s house, at the reading of the will. There was a question of property – trifling, now I look back – a hundred acres of grazing-land my father had promised to him in conversation, but which the will assigned to me. He said I had influenced the old man in his dotage. I said he was grasping and ungrateful. We spoke hotly. I – God forgive me – I struck him. Not hard, but enough. A blow to the shoulder, the mark of which he carried for a week.

We did not speak again before he shipped out to Bengal.

So you see, sir, this vindication is salt in the wound. I have proven him innocent of the charges laid against him. I have restored his name. But I cannot restore the years we lost, nor take back the blow, nor hear his voice again in this life.

There was a man – I must speak of him now, for the thought is upon me like a hand at my throat – there was a man who might have prevented all of this, had I heeded him. My uncle, my mother’s brother, who kept a school at Truro and whom I loved as dearly as any father. He was a stern old Methodist, thin as a riding-whip, with a face carved from Cornish granite and a voice that could shake a chapel roof. But he was kind. When I was sent to him at thirteen – my parents despairing of my temper – he did not beat the rashness out of me. He taught me instead to count to twenty before I acted in anger. “The Lord gave you a tongue and a brain, boy,” he would say, “so that you might use them before your fists.”

I loved him for that. He never made me feel a fool, though I deserved it. He would walk with me along the Truro quays when I was sullen or shamed, and speak to me of his own youth – of mistakes he had made, of hasty words that cost him friendships, of the long labour of learning patience. He died when I was seventeen, of a stroke, sudden as a thunderclap. I wept at his funeral as I have not wept since.

Had I written to him before that quarrel – had I asked his counsel – he would have told me to wait, to breathe, to let the heat pass. He would have reminded me that my brother was flesh of my flesh, and that property is dross compared to blood. I knew this. I knew it, even as I raised my hand. But I am my mother’s son, and I struck first and thought after.

Now I carry the consequence. My uncle’s lessons are carved upon my heart, but they came too late for my brother’s sake.

The captain tells me we shall sight the Lizard tomorrow if this wind holds. Home. Homeland. England. I have dreamt of it every night since Suez – the smell of woodsmoke and wet earth, the sound of church-bells on a Sunday morning, the particular grey of a Somerset sky. I have been too long in the heat and the dust, amongst strangers who do not know my name or my family’s standing. I want my own country. I want my wife’s arms and my children’s voices. I want to lay my brother’s bones in English ground and hear the parson say the words over him, and know that it is finished.

But I fear the homecoming, too. For what am I now? A man vindicated, yes. A man who has done his duty to the dead. But also a man who lives with the knowledge of his own rashness, his own unforgiving pride. My brother’s honour is restored, but mine is tarnished in my own sight. I cannot forget the blow. I cannot unknow the truth of myself.

The sea is grey and cold, and the gulls wheel overhead, crying like lost souls. I watch them and think: justice is a poor substitute for mercy. Vindication is a hollow triumph when the one you sought to vindicate is dead. I have won the battle, but I have lost the war. And all my life, I shall carry this wound – invisible, unhealable – the wound of knowing I was right, but that being right has bought me nothing but grief.

Tomorrow, England. Tomorrow, the reckoning. Tonight, I stand at this rail and let the wind scour me, and I do not weep. For tears would be an indulgence I have not earned.

You ask why I smile. I smile, sir, because vindication is bitter, and I have learned to swallow bitter draughts. I smile because I have no other expression left that will serve. And I smile because I am my mother’s son, and we are a hasty, proud, ungentle people who do not know how to grieve with grace.

God have mercy upon us all.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment