This interview is a dramatised reconstruction built from historical sources about Evelyn Berezin’s life and work, not a real transcript – she died on 8th December 2018, and the conversation is imagined as taking place in December 2025. Wherever the record is incomplete or contested, the dialogue reflects best-supported facts and clearly signposts interpretation rather than claiming certainty.

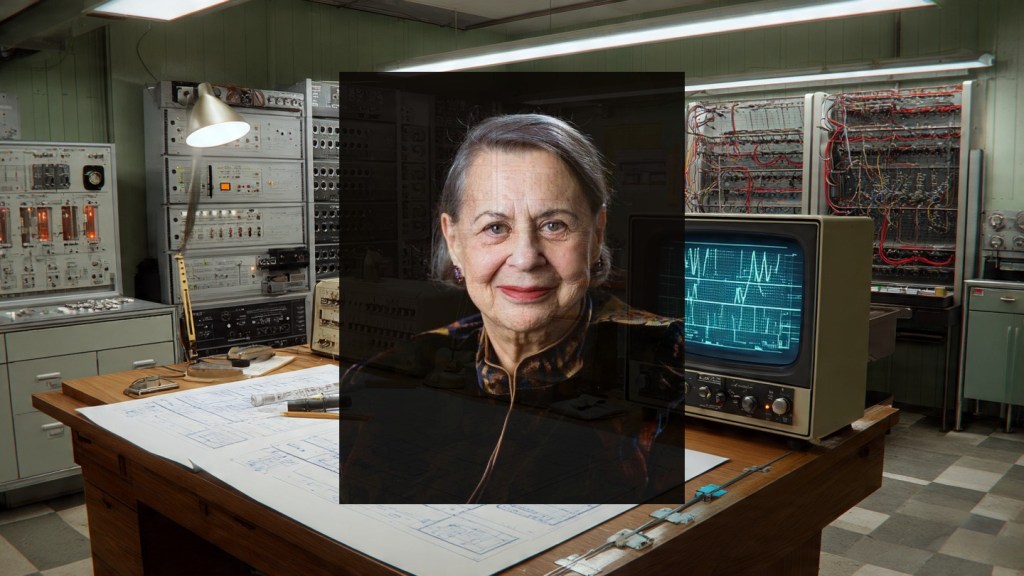

Evelyn Berezin (1925 – 2018) was an American computer pioneer and entrepreneur who designed the first computerised airline reservation system and invented the first electronic word processor. Born to working-class Belarusian Jewish immigrant parents in the Bronx, Berezin taught herself logic design and systems architecture despite having no formal training in computer science, ultimately leading departments and founding her own technology company when such achievements were extraordinarily rare for women.

Good morning, Evelyn. It’s an honour to sit down with you. I should begin by saying that today – 14 December 2025 – is seven years after your passing in 2018, and the world has changed considerably since then. Yet in many ways, you’ve become more visible in recent years, particularly the 2020 posthumous induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. I wonder what you’d make of that?

Seven years! I’ve missed quite a lot then. Well, the posthumous honour – that’s bittersweet, isn’t it? I would have been ninety-five. Too old to be properly famous, I suppose. I always said that late recognition doesn’t help you build a field or mentor young people. By the time they put your name on the wall, you’re too tired to climb it. But I’m grateful. That’s not false modesty – I genuinely am. It just would have been nicer at seventy-five, when I still had energy to actually do something with it.

The 2015 Computer History Museum fellowship – that one did warm my heart. I was ninety then, and I remember thinking, “Well, finally.” Not that I was waiting around for validation all those years. I was far too busy actually working. But yes, it mattered to know that the industry remembered what I’d built.

Your work is everywhere now, but invisible. Every airline reservation system, every word processing application, every real-time banking transaction traces its ancestry back to principles you pioneered. Can you speak to that paradox – that your innovations became so thoroughly integrated into everyday life that the inventor disappeared?

That’s the core of it, isn’t it? The best infrastructure should be invisible. If the airline reservation system is working, you don’t think about it. If your word processor saves a document smoothly, you don’t think about the engineering that made that possible. I take that as a compliment, actually.

But there’s a particular cruel irony in it. If I had built something that failed spectacularly – some machine that broke down constantly – people would remember the disaster and therefore remember the inventor trying to fix it. Instead, what I built worked so well and became so commonplace that it vanished into the wallpaper of the world. I liberated secretaries from retyping whole documents, and what happened? The invention itself became gendered as “secretarial” and therefore devalued. The tool that solved women’s problems lost status because it was for women’s problems.

Meanwhile, the male pioneers who built theoretical foundations – the operating systems, the programming languages – they became the heroes. Their work was “masculine” because it was foundational and abstract. Mine was “feminine” because it was applied and practical. But you know what? The world needed the practical systems far more than it needed another theorem.

Let’s go back to the beginning. You earned a physics degree and even worked on nuclear physics research. How did a physicist end up as a logic designer with no formal training in computer engineering?

By necessity and serendipity in equal measure, if I’m honest.

I was absolutely determined to be a physicist. My older brother had Astounding Science Fiction magazines, and I stole them constantly – utterly stolen. They convinced me that physics was the most exciting thing in the world. When I finally got to study it properly during the war – I was working full-time at International Printing Ink and going to night classes – it felt like I’d found my true home.

I worked on a really interesting project at NYU during graduate school. Three of us were building a cloud chamber on the roof, trying to measure meson energies using radioactive caesium-60. We had a lead-shielded box, but no top on it. We just sat there getting doses of radiation, utterly unconcerned because nobody really understood radiation sickness yet. You knew it existed, but it was abstract.

I almost finished a doctoral thesis, but then the Korean War happened and Truman decided the government wasn’t going to hire anybody. Physics jobs vanished. I got married, my husband went to Israel, and I needed to earn money. My thesis advisor sent me to a headhunter, and I asked – completely out of nowhere – whether there were any jobs in computers. To this day I don’t know why I said it. I must have read something somewhere, seen something in a magazine. But the headhunter got a call that very morning from someone in Brooklyn looking for computer people.

That’s luck. I’ve spent my whole life being astonished by my own luck.

I walked into Electronic Computer Corporation in October of 1951, completely ignorant of computers, and Gene Leonard – the head of engineering – asked me to design a circuit. I did it, and he hired me on the spot as his logic designer, which was a department that didn’t even exist yet.

So I didn’t train to be a computer designer. I became one by designing a machine.

You were the sole logic designer for machines with magnetic drums and stored programs. Walk me through what that work actually involved – not for the historians, but for someone who wants to understand what you physically had to figure out.

The Aberdeen machine – that’s the gun-range calculator I designed first – it was all vacuum tubes. Thousands of them, generating terrible heat in the summer. No air conditioning in Brooklyn in those days. You’d literally see the men walking around with barely any clothing on. I at least wore clothes.

Logic design is a very particular craft. You’re taking a requirement – “we need to calculate this trajectory” or “we need to store this data” – and you’re translating it into electrical circuits. Tubes or later transistors. You’re thinking about how current flows, how to create AND gates and OR gates and NOT gates. How to combine them to make a circuit that computes something meaningful.

The stored-program concept – that was revolutionary. You could load instructions into memory, and the machine would execute them. Not plug-board programming, where you physically wired up your instructions every time. That’s what made it a computer rather than just a calculator.

Memory was the constraint. We used magnetic drum – about 35 inches high, 20 inches around. You had a read head and a write head at specific distances from each other, and as the drum rotated, you could store and retrieve data. But it was serial. You couldn’t just reach into memory anywhere you wanted. You had to wait for the drum to rotate to the right position. Everything operated in sequence.

I designed recirculating delay lines on the drum – that sounds fancy, but it was elegant simplicity. The writer would continuously write new data as the drum rotated, and the reader would pick it up when it reached the right position. It worked, and it was reliable.

The hardest part wasn’t the circuit design itself. It was the logic, the overall architecture. How do you make a system that can hold instructions and execute them in the right order? How do you handle branching – if-then-else operations? How do you make it fast enough to be useful when you’re stuck with drum memory?

I had no formal training in this. I learned by reading the designs that the engineers who came from UNIVAC had sketched out, understanding the principles, and then building out the entire circuit myself. I worked alone. There was nobody to ask. If I got something wrong, we’d test it and try again.

That’s why people ask me how I learned without formal education. The answer is: you have to pay attention. You have to think carefully. You have to not be afraid of being wrong, because you will be wrong, and you have to know how to fix it.

Let’s get specific. Tell me about the Reservisor – the airline reservation system you designed at Teleregister for United Airlines. This was genuinely one of the largest computer systems of its era, and it needed something that hadn’t been solved before: one-second response time across a nationwide network.

That was 1957 to roughly 1962 when it was delivered, and it was the most complex system I had ever designed. Let me be clear about the scale: we were serving 60 cities across the United States. A travel agent in Denver or Chicago or Los Angeles needed to query the central system in real-time and get an answer back in about one second. Can you imagine what people in 1962 thought about one-second response time? To them, it was like magic.

The naive approach would be one big central computer. But that’s a single point of failure. If it goes down, your entire reservation system collapses. United Airlines couldn’t tolerate that. They needed something that could keep working even if one processor failed.

So we designed a system with three independent but linked processors at the centre. Triple redundancy. Each processor had its own drum memory. If one failed, the other two could maintain operations. The system had no central system failures in eleven years of operation. Eleven years. That’s the kind of reliability you need for something as critical as booking flights.

The network part was the hard part. We had to transmit reservation requests from hundreds of agents simultaneously across dual microwave loops – one primary, one backup. Each agent at a terminal needed an answer back in one second. The processors had to handle concurrent requests, manage the inventory of available seats across all 1,000 flights that we could store, and deal with constantly updated information about cancellations, rebookings, all of it.

One second. That sounds trivial now. Your phone responds in milliseconds. But in 1962, a one-second response time over a nationwide network using transistor-based computers was cutting-edge engineering. We had to think about every microsecond. Every instruction cycle mattered.

The transistor was crucial. At Teleregister, we were early adopters. Other companies were still using vacuum tubes, and we said no – transistors are smaller, faster, more reliable, generate less heat. They consumed less power. For a system that had to run reliably for eleven years, transistors were essential.

I taught a department of ten people how to design electronic logic. Not computer science – logic. How to think about circuits, how to make them reliable, how to test them. Most of them had never done this before. I learned by teaching, in a sense. You have to understand something deeply to explain it to someone else.

One thing that people forget: the airline reservation system predated Sabre by several years. American Airlines developed Sabre, and it got more attention because American Airlines was good at publicity. But United Airlines had the Reservisor, and it worked. Not as well as Sabre eventually, but it worked. Yet when people write the history, they focus on Sabre. The victors write the histories.

By 1969, you decided you’d had enough of working for other people. You founded Redactron. Walk me through that decision and the early days of the company.

I was frustrated. Endlessly frustrated. I was one of the only women in engineering departments where I worked. I could do the job – I’d proven that repeatedly – but I couldn’t seem to advance beyond a certain level. There were men below me in technical skill who were being promoted. There was the New York Stock Exchange job offer that got retracted explicitly because I was a woman. The excuse was absolutely honest, by the way: they said the language on the trading floor wasn’t suitable for a woman’s ears.

I realised that I’d never be a senior manager at an established company. Not because I lacked the ability, but because the system wasn’t built to accommodate women in that role. So I decided: I’ll start my own company.

I’d been thinking about the word processor concept for years. I was paying attention to secretaries’ frustrations – they had to retype entire documents for a single typo. Entire documents! The inefficiency was staggering. And I thought, why isn’t there a machine that lets you edit text digitally before you print it? It should be straightforward. You type it, you save it, you make corrections, you print a clean copy.

IBM had the MT/ST – Magnetic Typewriter with tape storage. But it used relay switches and magnetic tape, and it was, frankly, klutzy. It wasn’t really a computer. I knew we could do better using integrated circuits. Small chips, reliable, cheap to manufacture.

I founded Redactron in 1969 with the idea of building a dedicated word processor. We started with nine people. Nine! That’s it. We moved into our first building in December of 1969, and I had to design not just the system, but the integrated circuits themselves, the control logic, all of it.

Here’s where we nearly failed: I wanted to buy processors from Intel. They were new, they were making memory chips, and I thought they could manufacture what we needed. I went to them and said, “I need custom chips for this word processor system.” They looked at me and said, “Sorry, we’re too busy with memory orders.”

Too busy to sell us chips!

So we had to design some of the chips ourselves and then get other manufacturers to produce them from our schematics. That was expensive and complicated, but it forced us to be very clever about the design. We ended up with a system that used 13 semiconductor chips, some of which I personally designed.

The Data Secretary was about 40 inches tall – roughly three and a half feet. The size of a small refrigerator. It had an IBM Selectric typewriter for input and output. Magnetic tape cartridges for storage. No screen initially – we knew that was a limitation, and later versions added a monitor. But the core concept was sound: type on the Selectric, the text gets stored digitally on tape, you can edit it, and then you can print it out cleanly.

We delivered our first machines in September of 1971. By 1975, Redactron had nearly 500 employees. We had factories, service organisations, a worldwide marketing setup. It was astonishing. I went from nine people to 500 in less than six years.

Of course, we faced competition. Lexitron came out with a machine that had a display screen, and that was better for the user. But our Data Secretary was reliable, it worked, and it proved the concept: a computer built specifically for word processing could liberate secretaries from the tyranny of the typewriter.

We sold the company to Burroughs Corporation in 1976, and I stayed on as president of the Redactron division until 1980. It was successful by any reasonable measure. It just wasn’t Apple or Microsoft, so it doesn’t loom large in the mythology of tech.

You’ve had decades to reflect on your career. Is there anything you’ve genuinely changed your mind about? Any decisions you look back on and think, “I would have done that differently”?

Yes. The transistor choice at Teleregister – I was right about that, but I underestimated how difficult it would be for the entire industry to convert away from tubes. We were early enough that we faced real resistance. Some customers wanted tubes because they understood tubes. Transistors were new and scary. I was convinced we were right, and we were, but I could have been more diplomatic about the transition. People don’t like being told their proven technology is obsolete.

Second thing: I was too focused on special-purpose systems. The Reservisor was brilliant for airline reservations, but it was only for airline reservations. The Data Secretary was brilliant for word processing, but it was only for word processing. I designed systems to solve specific problems, and I solved them wonderfully. But I didn’t think about how to make them general-purpose tools.

The industry went the opposite direction. They built general-purpose computers – IBM System/360, then minicomputers, then personal computers. Everything became software running on general hardware. My dedicated hardware approach was technically superior in many ways – more efficient, more reliable, faster for the specific task. But it was economically doomed. You can’t keep designing new hardware for every new application. You have to have an abstraction layer.

So do I regret the Data Secretary being dedicated hardware? No. It was the right choice for 1969. But I wish I’d anticipated that the future would belong to general-purpose computing. If I’d thought about that in time, maybe Redactron could have pivoted earlier and survived longer.

What would I defend? All of it. The work was honest and well-engineered. I designed systems that solved real problems for real people. I managed to run those systems reliably for years. I founded a company when women couldn’t get business credit without a male co-signer. I taught people how to think about logic design from first principles. I paid attention to what users actually needed instead of building what I thought was clever.

I’m not going to apologise for building practical systems instead of theoretical foundations. Practical systems are how ordinary people experience technology.

You’ve lived through the entire history of modern computing, essentially from its inception, as one of the only women in technical roles. How did that actually feel – not as an abstract historical fact, but day-to-day?

It felt lonely.

At Brooklyn Polytechnic – where I went for my math courses during the war – I was literally the only woman who had ever attended. The only woman, ever. I had this trail of boys following me around. It was meant to be kind, I think, but it was also very noticeable. I couldn’t just be a student. I was The Woman.

At Electronic Computer Corporation, I designed the entire logic for machines by myself. There was nobody I could ask, nobody I could collaborate with, because the other engineers were working on different aspects – mechanical design, the shop work, input-output. The logic design was just me.

It means you have to be very sure of yourself. You can’t afford self-doubt. If you doubt yourself, you’ll make mistakes, and when there’s nobody to catch your mistake, the mistake gets built into the machine. I developed this intense focus: check the work, check it again, ask questions, test assumptions. I became someone who couldn’t tolerate sloppy thinking.

But it also meant I was watched differently. When a man made a mistake, it was a mistake. When I made a mistake, it confirmed that women couldn’t do engineering. There was this permanent scrutiny. You had to be perfect because you were the representative.

The New York Stock Exchange thing – that was overt discrimination, but it was also almost refreshing in its honesty. They said explicitly: “We can’t hire you because you’re a woman. The trading floor language isn’t suitable.” At least I knew where I stood. I wasn’t wondering if it was a competency issue or a personality conflict. It was simply sexism.

What I never quite got over was the invisibility of women’s technical contributions. The programming work, the logic design, the systems engineering – there were women doing it, and their names weren’t recorded. When historians look back, it’s men and men and perhaps one woman, and that one woman is always described in relation to a man. She worked with him, or for him, or as his assistant.

I was never anyone’s assistant. I was the head of logic design. I started a company. But I still had to fight for recognition as a full technical creator rather than a support role.

The worst part? I came to accept it. I stopped being angry about the sexism and just worked around it. And I wonder if that acceptance – that normalisation of being the only woman in the room – is why so much of the invisibility happened. I was too busy solving problems to keep meticulous records of my contributions. I wasn’t trying to build a personal brand. I was trying to make things that worked.

Let’s do a deep technical walk-through of the Data Secretary. I want to understand not just what it did, but how you actually made it work – the specific engineering challenges, the trade-offs, what made it function when nothing quite like it had existed before.

Right. So the problem is: how do you let someone type text, edit it, and print it cleanly without having to retype the entire document?

The obvious answer at the time was to use the IBM Selectric typewriter as your interface. The Selectric was revolutionary – it had a rotating typing element, almost like a golf ball, that could change position rapidly to strike any character. It was fast, reliable, and could be driven electronically. Perfect input and output device.

For storage, we needed something that could hold text and be reliable. Magnetic tape was the obvious choice. We used tape cartridges – essentially cassettes – that could hold thousands of characters. The mechanics of reading and writing tape were proven technology, but we needed to control it electronically.

Here’s where the integrated circuits came in. We couldn’t use off-the-shelf processors that Intel was making – they were too general-purpose and too slow. We needed something optimised for word processing: capturing keystrokes, storing them on tape, retrieving them, sending signals back to the Selectric to replay the text.

I designed a control processor – essentially a sequencer – that would:

- Read a keystroke from the Selectric

- Encode it and write it to tape

- Accept editing commands (delete, insert, move back, move forward)

- Remember the current position in the document

- Send the right signals to the Selectric at the right times to print text

The 13 chips I mentioned included memory chips, logic chips, and control chips. Most of them we sourced from manufacturers, but we designed the overall architecture and the sequencer logic ourselves.

The tricky bit was the timing. The Selectric has its own operational speed – a certain number of milliseconds per character. You have to synchronise your digital logic to that mechanical device. Too fast and you’ll miss a character. Too slow and you’re bottlenecking. We spent weeks optimising the timing relationships.

Then there was the magnetic tape interface. Tape can stretch, it can slip, environmental factors can affect it. You need error correction and redundancy. We had to encode the data in a way that was robust to tape defects. We built in checksums and verification.

The worst problem, which Ms Berezin has mentioned publicly, was static electricity. We held a demonstration in a New York hotel – very dry weather – and the system started sparking between circuits because the static buildup was so severe. Our big launch event, and the machine is literally sparking! We had to figure out proper grounding and shielding.

There was also the mechanical issue of the cassette drives. You need a cassette that won’t jam, that advances reliably, that can be read repeatedly without wearing out. We tested hundreds of cassettes, worked with suppliers to get tolerances right.

What I’m trying to convey is that it wasn’t just a clever idea. “Oh, let’s let people edit text!” That’s the concept. But the engineering – the actual making of a machine that reliably captured, stored, and retrieved text – involved countless small decisions, each one crucial.

We couldn’t afford a manufacturing mistake because every machine we sold would carry that mistake into the world. If the tape drive failed on the first unit we shipped, we’d have killed the whole company. So there was this incredible weight of responsibility.

But when you got it right – when you had a secretary in an office typing on the Selectric, making a mistake, pressing delete, having the tape back up and erase the error, and then being able to type the correction and print out a clean page – that was transcendent. That was engineering that mattered.

Here we are in 2025. Artificial intelligence is being integrated into office software at an extraordinary rate. There’s anxiety about automation replacing office workers, just as there was anxiety about word processors replacing typists. What would you say to people worried about that?

The anxiety is always the same, and it’s never quite right. When word processors came along, people said secretaries would disappear. They didn’t disappear. The work changed. Instead of managing a typing pool, you had secretaries using word processors to create more documents, better documents, with fewer errors. The number of office workers didn’t drop – if anything, it grew because now individual managers could create their own documents instead of dictating them.

The productivity gain was real. But the gain went to the company, not to the secretary. The secretary still made roughly the same money, still had the same job security, but now she could do three times the work in a day. So which side benefited? The employer.

But here’s what I want people to understand: automation is not predestination. Just because you can automate something doesn’t mean you have to displace people. You can retrain them. You can give them better work. You can share the productivity gains.

With AI now, yes, you can automate a lot of office work. You can generate documents, handle correspondence, organise information. But you could also use AI to make office workers’ lives better. Imagine AI that handles the most tedious parts of your job – the formatting, the organising, the searching through old emails. That frees you up for the thinking parts, the creative parts.

The tragedy would be if we automated people out of jobs without giving them better jobs to do. We have the technology to do that right now. We just need the will.

What I always believed, from the very beginning, is that technology should serve people. The Data Secretary didn’t replace secretaries – it liberated them from retyping. It let them focus on the substance of the work rather than the mechanics. That’s what technology should do.

If AI is used to make people obsolete, that’s a choice, not an inevitability. It’s a choice made by people who want to minimise labour costs. But if AI is used to enhance what people can do – to let them work better, faster, with less drudgery – then that’s real progress.

The Computer History Museum fellowship came when you were 90. The National Inventors Hall of Fame induction came posthumously. I imagine there’s something bittersweet about being recognised so late.

I’ll be honest: it stung a little when it happened too late to matter.

In 1990, when I was in my mid-60s and still working actively, that would have been something. That would have given me authority to speak about the field, to mentor younger people, to shape how the next generation of women engineers thought about their careers. By 90, you’re thinking about legacy, not about building the future.

But I also didn’t spend my life waiting for recognition. I was working. I was solving problems. I wasn’t designing computers because I wanted to be famous – I never would have been famous anyway, given the nature of my work. I was designing them because they needed to be designed.

What the late recognition does do is correct the record. It says: “You were here. You did this. It mattered.” That matters to historians. It matters to young women engineers who can now point to someone and say, “This woman did it first, and she did it alone, without fanfare.” That has value, even if it comes late.

I wish I could go back and tell my 25-year-old self that it would be OK. That she wouldn’t become famous, but she would make things that mattered. That she’d found a community that respected her work, even if the broader world didn’t. That she’d start a company and make it succeed. And that someday, decades later, people would still be talking about what she built.

But I also wouldn’t change anything if it meant I had to stop working. The work was the thing. The visibility was always secondary.

There’s a pattern in your career: you see a problem, you design a solution, you move on to the next problem. Secretaries are retyping documents – design a word processor. Airlines can’t handle reservations fast enough – design a real-time system. Banks are drowning in paperwork – design automated systems.

But you never tried to build monopolies or empires. Why?

Because the problems were interesting, not the money.

I mean, yes, I needed to earn a living. I liked being able to afford an apartment and not worry about bills. But once that was solved, the rest was just… solving problems. Building the best system I could build. Understanding the constraints and working within them.

If I’d been focused on empires, I would have tried to leverage the word processor into other products. I would have built an office software empire in 1975. But that wasn’t what interested me. The word processor was solved. I’d built it, proven it worked, made it reliable. Now what?

I looked around at what else needed fixing, and I found plenty. Banking systems, though I wasn’t directly involved in those later ones. Greenhouse management software – I did some consulting there in the 1980s. Board positions at various companies. Advisory work with start-ups.

I was never the kind of person to stay in one place and expand it infinitely. I liked new problems. I liked understanding new domains, learning new constraints, applying engineering principles to different industries.

Maybe that’s another reason I never became a household name. The really famous tech entrepreneurs – Gates, Jobs, others – they focused. They went deep on one problem and rode it for decades. I was more like a consultant who kept taking on new work.

But I don’t regret that. The word processor was brilliant for its moment, and I was happy to let it go when I’d solved the core problem. That’s the mark of good engineering – not hanging on to something that’s become obsolete or constraining, but knowing when to pass it on.

You’ve lived through an entire epoch of computing. What problems do you see in 2025 that remind you of unsolved challenges from earlier eras? What patterns do we keep repeating?

Infrastructure invisibility. We solved airline reservations, but now you have this vast internet infrastructure that’s even more invisible and even more critical. Millions of people depend on it constantly, but they never think about it. One failure and everything stops. We learned how to build reliable systems in the 1950s and 60s – redundancy, fail-safe design, careful monitoring. But I wonder if everyone building the internet infrastructure today knows those lessons? Do they?

Second: the gendering of work. We solved the word processor problem, but the work still gets devalued because it’s associated with secretarial labour, which is women’s labour. Today I see the same pattern with care work, with data entry, with content moderation. The work is essential and difficult, but it’s coded as “feminine” and therefore doesn’t command the attention or pay that “masculine” work commands. Until we solve that – until we stop devaluing the work that keeps organisations running – we’ll keep repeating the same mistake.

Third: specialisation versus generalism. I built special-purpose machines because that was the only way to get the efficiency and reliability we needed. The industry went general-purpose with software. But now I see these specialised AI chips coming back – TPUs, APUs, custom silicon for machine learning. The wheel turns. We’re learning that sometimes specialisation is more efficient. I wonder if that cyclical pattern will keep happening.

And finally: retention of knowledge. This is serious. I lived through the entire early computing era, and I’ve seen the knowledge required to build reliable systems fade away. Programmers today don’t need to understand the deep systems principles because the abstractions have gotten so good. That’s fine until you build something that requires those principles, and then you’re in trouble.

So much institutional knowledge was lost when companies disappeared, when people retired without documenting what they’d learned. I’m glad the Computer History Museum exists, because it’s trying to capture that knowledge before it evaporates. The oral histories matter. The documentation matters. Otherwise we’re destined to solve the same hard problems over and over.

There’s something I want to correct, actually. For the record.

The histories say – some of them – that the Data Secretary didn’t really count as the “first word processor” because it was hardware, not software. That IBM’s MT/ST was similar. That Wang invented the real word processor.

That’s nonsense, and it’s nonsense designed to erase women’s contributions.

The MT/ST was electromechanical. It used relay switches. It could store text on tape, yes, but the whole approach was kludgy and slow. Our Data Secretary used integrated circuits. We didn’t just bolt together existing parts – we designed the chips ourselves because nothing suitable existed. We built a computer, a real computer, to do word processing. That’s not a hack. That’s engineering.

Wang built a beautiful word processor. Wang deserves full credit for what he did. But chronologically, the Data Secretary came first, and it was more technologically advanced because we used ICs and programmable logic rather than electromechanical relays.

The revisionism that ignores this drives me absolutely mad. It’s the history-erasing that happens to women’s work in tech. Someone else comes along later and does something slightly better, and suddenly they become “the real inventor” and the woman who did it first becomes a footnote. I see it happening with my word processor. I’m sure it happened with other women’s inventions too.

What do you want people to understand about your work? Not your achievements – the historical record can sort that out eventually. But what lesson do you hope your life and work convey?

That engineering is a noble calling. Not noble in some abstract sense, but noble because it’s about making things that help people. I designed systems so that secretaries wouldn’t have to do mindless retyping. I designed systems so that travel agents could answer questions in one second instead of ten minutes. These aren’t glamorous problems. They’re practical. But they matter because they matter to people.

Second, that you don’t need official credentials to learn. I had no formal computer science education. I taught myself by doing. That’s possible in fields where you can build and test. Don’t let lack of credentials stop you if you have curiosity and willingness to work hard.

Third, that women belong in technical fields, not as secretaries or support, but as full engineers and architects and leaders. I was one of the few women in my era who had those roles. There should have been more. There should be many more now. It’s not about affirmative action – it’s about recognising that talent isn’t gendered. And the problems that need solving aren’t gendered. A woman can design a real-time systems architecture just as well as a man.

And finally: don’t chase fame. Do the work. Solve the problems. Build things that last. The recognition might come late or not at all, but the satisfaction of knowing you’ve built something reliable and useful – that’s its own reward. I spent fifty years in computing, and I spent most of those years utterly unknown outside my field. I was fine with that. I liked the work. The work was enough.

Evelyn, there’s a question many people want to ask but feel they shouldn’t. You lived to 93, and you lived through the birth of the entire modern computing era, yet you saw many of your inventions either absorbed by others or credited to men. Did that anger you? Do you still feel that anger?

I stopped being angry a long time ago. Anger is exhausting, and I had work to do.

But yes, I notice. I notice that when the history is written, my name is smaller than it should be. I notice that my contributions get simplified into one achievement – the word processor – when I did so much more. I notice that people act surprised that I was capable of what I actually did.

That’s not anger anymore. That’s just… awareness. A kind of sad recognition that my story is typical, not exceptional. There were other women whose work got erased or misattributed. There are women now whose work is being erased. It’s a pattern. And patterns can change, but they take a long time.

If I’m angry about anything, it’s about the waste of it. The talent that was wasted because women couldn’t get jobs in tech. The problems that never got solved because half the brains in the population were excluded from technical fields. That’s what makes me angry – not for myself, but for everyone.

But I’m not going to spend my remaining years – however many I have – being angry. I’m going to appreciate that the work I did mattered. That people are slowly beginning to understand that. And I’m going to hope that by the time young women graduate from college in 2030 or 2040, it will be utterly normal for them to be systems architects and logic designers and technical leaders.

That’s what I want. Not recognition for me, though I’ll take it. But a world where my story is unremarkable because women being excellent engineers is just… the ordinary state of things.

I think I’ll be disappointed on that timeline. But maybe I’m wrong. Maybe change is faster than I expect.

Questions from Our Community

Following the main interview, we received numerous thoughtful enquiries from readers, engineers, historians, and technologists around the world – people whose work and curiosity have been shaped by Berezin’s legacy, whether they knew it or not. From Wellington to Tokyo, from Stockholm to Casablanca and Austin, we selected five letters and emails that ask deeper questions about her technical decisions, her understanding of user-centred design, the knowledge that emerged from her work, and the counterfactual histories that might have unfolded differently.

These questions move beyond biography into the territories Berezin touched lightly in our conversation: the cyclical nature of hardware specialisation, the ethics of solving immediate problems without transforming structural inequalities, the invisible insights that industry practitioners create when academia isn’t watching, and the role of market positioning in determining whether an innovation becomes legendary or erased.

What follows are her responses to five contributors who represent the global community of engineers, historians, and thinkers still learning from her example – and still asking the questions that matter most.

Marama Rangi, Wellington, New Zealand | Software Engineer & Open-Source Contributor (Age 34)

You mentioned that the Reservisor achieved a one-second response time using triple-redundant processors and microwave loops in the early 1960s. Today we have millisecond response times, cloud failover, and distributed systems across continents. But I’m struck by something: your constraints were physical – the speed of light through wires, the rotation speed of magnetic drums, the mechanical limits of the Selectric typewriter. My constraints are algorithmic and financial.

When you were designing for the Reservisor, how did you think about the trade-off between achieving absolute speed versus achieving reliable, predictable speed? Because one-second response is slow by modern standards, but it was apparently reliable for eleven years. Were you deliberately choosing “good enough speed” if it meant the system wouldn’t surprise you? And do you think modern engineers even think about predictability the way you had to?

Marama, this is a very good question, and I appreciate that you’re thinking about the philosophy of design, not just the mechanics.

You’re right that my constraints were physical in a way yours aren’t. The drum rotated at a fixed speed. The microwave signal travelled at the speed of light – you can’t make it faster. The Selectric typewriter had mechanical limits. You work within algorithmic constraints and financial ones, which are different animals entirely. But the principle, I think, is the same: you design for the real world you’re in, not the world you wish you were in.

One second wasn’t fast. I knew it wasn’t fast. But it was fast enough, and more importantly, it was predictable. That’s the distinction you’re picking up on, and you’re absolutely correct that it mattered more than raw speed.

Here’s what I mean: if you design a system that sometimes responds in half a second and sometimes in three seconds, your users go crazy. They don’t trust it. They start developing workarounds. The travel agent at the terminal in Chicago stops relying on the system and keeps a backup manual card file. That defeats the purpose. But if you design a system that consistently responds in one second – always one second, you can set your watch by it – then the user learns the rhythm. She adapts. She integrates the system into her workflow.

The way we achieved that predictability was through careful management of the entire pipeline. The request comes in over the microwave loop. It gets queued. The processor picks it up in the next available cycle. The drum rotates to the right position. The read head picks up the seat inventory. The calculation happens. The write head stores the update. The response goes back out. All of this had to happen in approximately one second, every time, no matter how many requests were coming in.

We couldn’t afford jitter. We couldn’t afford surprises. So we built in slack. We overspecified the processor speed so that even under peak load, we weren’t hitting the ceiling. We designed the queue management so that no single request would jam the system. We tested exhaustively under load conditions – we’d simulate hundreds of simultaneous requests and watch the response times.

I’ll tell you something that doesn’t usually get mentioned: we deliberately didn’t try to push the system to its absolute theoretical limits. We could have squeezed another 200 or 300 milliseconds out of it with more aggressive design. But then we would have had no margin for error. One unexpected load spike and the whole thing would have degraded. Instead, we left room. We designed conservatively.

This is where I think modern engineers sometimes miss something important. You have so much computational power now that there’s a temptation to use it all. Every bit of it. To squeeze out the maximum performance. But that leaves you fragile. It leaves you with systems that work perfectly in the lab and then behave unpredictably in the real world where load patterns are messy and unpredictable.

At the Reservisor, we had eleven years of operation with no central system failures. Eleven years. I’ve never heard of a modern system achieving that kind of reliability record, and I think part of the reason is that modern systems are designed to the edge of their capability rather than with margin built in.

Now, do I think engineers today think about predictability the way we did? Honestly, I don’t know. I haven’t worked in computing for decades now. But from what I read, it sounds like the focus is on throughput – how much can the system handle – rather than on consistency – will the system behave the same way every time? And those are different optimisation goals.

The other thing you might consider: we didn’t have the option of throwing more hardware at the problem. If we needed more processing power, we had to build it. It was expensive and time-consuming. So we became very efficient at using what we had. We couldn’t afford waste. Modern systems can afford waste because hardware is cheap. You have redundant servers, you have failover systems, you have multiple copies of data. That’s wonderful for reliability, but it can make you sloppy about the design of individual components.

I’m not saying the old way was better. I’m saying it was different, and different constraints create different solutions. Your world is bigger and faster and more distributed than mine was. But I’d encourage you to think about whether there are things you’re optimising for – maybe throughput, maybe raw speed, maybe flexibility – at the cost of something I cared about: predictability and reliability under real-world conditions.

That might be worth examining.

Arata Kobayashi, Tokyo, Japan | Computer Historian & Museum Curator (Age 56)

You worked in an era before computer science was formalised as an academic discipline. There were no textbooks on real-time systems design, no conferences publishing peer-reviewed papers on transistor logic. You learned by building and testing. But here’s my question: what knowledge did you accidentally create that you didn’t realise was important?

For instance, were there principles you developed solving the Reservisor’s problems – about redundancy, about timing, about user-system interactions – that you never formally documented because they seemed obvious to you at the time? And looking back, are there insights from your work that the academic computing literature still doesn’t capture, simply because it emerged from industry practice rather than theoretical research?

Arata, you’ve identified the critical issue: the knowledge that vanished because nobody thought to write it down.

Let me give you a concrete example. When we were building the Reservisor, we discovered something about how human operators interact with real-time systems under stress. A travel agent has a customer on the phone. She’s asking about flights from New York to San Francisco on a specific date. The agent types the query into the terminal. She gets a response. But if that response takes three seconds instead of one second, her entire interaction with the customer changes. She feels the delay. She starts improvising, reassuring the customer, filling the silence. And then when the answer comes back, she’s halfway through an apology that isn’t necessary anymore.

We learned that response time isn’t just a technical specification – it’s a social specification. It affects human behaviour. If you want an operator to trust and use your system, you have to match her expectations about how long thinking takes. We built one second because that seemed to be the threshold where the operator didn’t feel abandoned.

Did I write that down? No. It wasn’t in any specification document. I mentioned it in passing to my team, and they understood it because they were watching the operators too. But it wasn’t formalised. It wasn’t published. It just became embedded in the design decisions we made.

Years later, I read some papers on human-computer interaction – this was in the 1980s, I think – and they were discovering these same principles as if for the first time. They were measuring response time thresholds, talking about user expectations, building models of how humans perceive delay. And I thought: we knew this in 1960. We just didn’t have the vocabulary or the academic infrastructure to claim it.

There are dozens of these insights. We learned about redundancy through trial and error. We discovered that you can’t just have three independent processors – you have to have a way for them to agree on what the current state is, otherwise they diverge. We called it “keeping the processors in sync,” but what we were actually doing was solving the consensus problem in distributed systems. That’s a hard problem in computer science. People publish papers on it now. We just had to solve it to make the airline system work, so we did.

We learned about tape reliability by having failures and figuring out what went wrong. We discovered that magnetic tape degrades in certain environments – humidity affects it, temperature affects it. We developed techniques for encoding data with redundancy so that if part of the tape was damaged, you could still read the information. That’s error-correcting codes. But we didn’t call it that. We just needed the data to survive.

We learned about the economics of reliability. It costs money to build triple redundancy. It costs even more money to test it thoroughly. At what point does the cost of additional reliability exceed the cost of occasional failures? We made decisions about that without any formal framework. We guessed, based on United Airlines’ tolerance for downtime and our intuition about what was achievable. We were lucky that our guesses were right.

What I think happened is this: computer science became an academic discipline, and academics value certain kinds of knowledge – theorems, formal proofs, generalisable principles. But industry practitioners were generating knowledge of a different kind: knowledge about how to actually build things that work in the real world. And those two kinds of knowledge don’t always overlap.

The academic world didn’t really care about “how do you design a reliable system that serves 60 cities simultaneously,” because that’s too specific. But they should have cared, because embedded in that problem are insights about distributed computing, about human factors, about the relationship between specification and implementation. Those insights could have informed theory. Instead, they just disappeared.

I think your museum work is valuable precisely because you’re trying to recover this lost knowledge. You’re interviewing engineers, documenting their decisions, capturing the reasoning behind choices that were made decades ago. Because otherwise, yes, the knowledge evaporates. The people retire or die, and the only thing left is the machine itself, which people can look at but not fully understand.

One more thing, and this is important: I don’t think the problem was that we didn’t know what we were doing. We knew. We understood the principles. But we didn’t have the language or the theoretical framework to express what we knew in a way that would have been publishable in academic journals. So it stayed local. It stayed in Brooklyn, at Teleregister, in the heads of the people who built the systems.

If I could go back, I would document everything more carefully. I would write down not just what we did but why we did it. I would try to generalise from the specific problems we solved to broader principles. And I would push harder to get that knowledge into the academic literature, where it could be examined and debated and built upon.

But honestly, I was too busy building the next thing to worry about documenting the last thing. That’s a luxury you have now – the ability to pause and reflect and write things down. We rarely had that luxury. We just moved forward.

Freya Lindgren, Stockholm, Sweden | Hardware Engineer, Semiconductor Design (Age 29)

You designed 13 custom semiconductor chips for the Data Secretary rather than using off-the-shelf Intel processors. You’ve acknowledged that the industry ultimately chose general-purpose machines running software over specialised hardware. But here’s what puzzles me: in 2025, we’re seeing this reversal. Custom TPUs for machine learning, bespoke silicon for AI inference, purpose-built processors for edge computing.

Do you think your instinct about specialised hardware was actually ahead of the curve rather than a dead end? And if you could go back to 1971 knowing what we know now about the cyclical nature of specialisation – that the pendulum swings back – would you have approached Redactron’s manufacturing strategy differently? Would you have pushed harder to prove that custom silicon had longevity?

Freya, you’re touching on something that’s been a sore point for me for fifty years, so I’m glad you asked.

Yes, I think we were ahead of the curve. Not too far ahead – we weren’t visionary in some mystical sense. But we understood something that the industry collectively forgot: sometimes a general-purpose solution is less efficient than a specialised one, and efficiency matters.

In 1971, when we were designing those 13 chips for the Data Secretary, the conventional wisdom was already shifting toward general-purpose computers. Buy an IBM System/360, or a minicomputer, load word processing software onto it, and you’ve got your solution. Why build custom hardware? It’s expensive, it ties you to one product, it can’t adapt to new requirements. General-purpose machines were flexible, and flexibility was being valued above all else.

But here’s what people weren’t measuring: cost per unit of work done. The Data Secretary used custom chips because we could optimise every gate, every transistor, for the specific task of word processing. We didn’t need a full instruction set. We didn’t need the overhead of an operating system. We could make the machine smaller, faster, and more power-efficient than a general-purpose computer running word processing software would ever be.

The trade-off was real. If a customer wanted to add a spreadsheet function or a database, we couldn’t do it. The system was locked into word processing. But for the 90 percent of customers who just wanted a machine that processed words reliably, it was superior.

I wasn’t wrong about that. The physics and the economics both supported specialised hardware. What I was wrong about – or rather, what I couldn’t have predicted – was how dramatically the cost of general-purpose computing would fall, and how that would change the entire calculus.

By the late 1970s, microprocessors became incredibly cheap. The Intel 8080, the 6502, later the 68000 – these were powerful enough to run word processing software, and the cost per unit kept dropping. Suddenly, the economics flipped. It was cheaper to use a cheap general-purpose processor with software than to design custom silicon. The flexibility advantage of software became more important than the efficiency advantage of custom hardware.

That was a genuine technological shift, not a failure of vision on my part. But it meant that specialised hardware became a dead end, at least for a while. Companies that had invested in specialised approaches – including Redactron – found themselves on the wrong side of history.

Now, here’s where you’re interesting me with the TPU and custom silicon coming back. I’ve read a bit about this. Machine learning requires so much computation that optimising for the specific workload matters again. You can’t just throw a general-purpose CPU at it and expect efficiency. You need custom silicon.

If that’s true – and it sounds like it is – then yes, my instinct was correct. The general-purpose era wasn’t inevitable. It was just an interregnum, a period when the economics favored flexibility over specialisation. But as workloads became more demanding and more specific, the pendulum swings back.

Would I have done anything differently at Redactron knowing that? Honestly, I don’t know. The problem wasn’t that we should have invested more heavily in custom silicon. The problem was that we couldn’t have predicted the cost curve of microprocessors. Nobody could have. That’s not a failure of foresight – that’s just how technology works. You make decisions based on the information you have.

What I might have done differently is think about the business model. Instead of trying to manufacture and sell dedicated word processors, maybe we should have been designing the chips and licensing them to other manufacturers. Let IBM, Xerox, and others build the systems. We’d be the silicon supplier. That would have given us more flexibility and less capital exposure.

But that would have required a different kind of entrepreneurship than I was equipped for. I wanted to build the complete system. I wanted to see the machine work end-to-end. Licensing chip designs to other companies felt like giving up control, and I wasn’t comfortable with that.

So maybe the real lesson is this: I was right about the technology, but I was wrong about the business strategy. The technology – custom silicon for specialised workloads – had a future. But the business model – manufacturing and selling complete systems as a small company competing against IBM – didn’t. If I’d understood that distinction better, maybe Redactron would have evolved differently.

Would we have become another major player in semiconductors? Probably not. We didn’t have the capital or the distribution network that Intel or Motorola had. But we might have carved out a niche as a design house for specialised processors, rather than trying to be a systems manufacturer.

That’s hindsight talking, though. At the time, we didn’t have the option of stepping back and designing elegant business strategies. We had to move fast, sell machines, keep the company afloat. You do what you can with what you have.

The encouraging thing, from my perspective, is that you’re asking these questions now. You’re thinking about when specialisation makes sense and when it doesn’t. You’re not blindly following the dogma that general-purpose is always better. That’s the kind of independent thinking that produces good engineering.

And if specialised hardware is coming back because machine learning demands it, then the engineers designing those TPUs and custom processors should learn from what we did. Pay attention to power efficiency. Pay attention to the specific workload. Don’t add capabilities you don’t need. Keep it focused. We made those chips work beautifully for a specific task, and that’s a model worth repeating.

Just do it with better business planning than I did.

Liam O’Sullivan, Austin, Texas, United States | AI Ethics Researcher & Former Software Architect (Age 38)

Suppose that in 1969, instead of founding Redactron to sell word processors to businesses, you’d licensed your Data Secretary design to a consumer electronics company – imagine if RCA or Zenith had manufactured it as a desktop appliance for home offices. What would have been different?

Would you have become a household name like Jobs or Wozniak? Would your company have had a different trajectory? Or would the Data Secretary, positioned as a consumer device for home use, have faced barriers that B2B systems never encountered? I’m asking because I suspect the invisibility of your work wasn’t entirely about being a woman – it was partly about building B2B infrastructure rather than consumer products. But I’m curious whether you think a consumer version of your innovation would have changed the outcome, or whether the same erasure would have happened regardless of the market you served.

Liam, this is the question that makes me wonder about parallel universes, because I’ve thought about it more than I’d like to admit.

Let me be clear about why we didn’t go the consumer route: it never occurred to me as a viable option. Redactron was founded to sell word processors to businesses because that’s where the money was. A secretary in a law firm, a hospital, a bank – these organisations had budgets for equipment. A homeowner? In 1969? The idea of someone having a word processor in their living room seemed absurd. Typewriters were still the standard for home use. Why would you spend $10,000 on a dedicated word processor when you could buy a typewriter for $200?

The consumer market for personal computers didn’t really exist until the mid-1970s, and even then, people didn’t know what to do with them. The Apple II came out in 1977 – eight years after we founded Redactron – and it took years before word processing became a “killer app” for personal computers.

So the timing alone would have made a consumer play impossible. We didn’t have the product category. We didn’t have the distribution channels. Department stores weren’t set up to sell office equipment. We couldn’t have done it, even if we’d wanted to.

But let me play out your hypothetical anyway, because it’s interesting.

If RCA or Zenith had licensed our design and manufactured it as a consumer appliance in, say, 1975 or 1976 – which is when personal computers were starting to emerge – what would have happened?

First, they would have had to solve the price problem. A Data Secretary cost roughly $10,000 to $15,000 depending on configuration. RCA and Zenith had manufacturing scale that we didn’t have, so they might have gotten the cost down to $5,000 or $6,000. That’s still expensive for a home product, but not impossible. The early personal computers cost $2,000 to $3,000, so we’re in the same ballpark.

Second, the marketing problem. RCA could have sold it as a prestige product – “The word processor for the executive’s home office.” Zenith could have positioned it as a home productivity device. They had the brand recognition and the retail presence to make that work. We didn’t.

Third – and this is crucial – they would have had to compete with the Apple II and the Commodore 64 and the IBM PC, which started arriving in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Those machines were general-purpose computers that you could load word processing software onto. WordStar came out in 1979. Later you had WordPerfect and Microsoft Word. These were cheap compared to buying dedicated hardware.

So even if RCA or Zenith had manufactured our design and sold it to consumers, they would have been competing against general-purpose computers running word processing software. And they would have lost, for the same reason Redactron lost. Not because of the hardware design – it was good. But because general-purpose machines were more flexible and cheaper.

Now, would I have become a household name if a major corporation had licensed my invention? That’s the real question you’re asking. And honestly, I don’t think so.

Look at what happened to Nolan Bushnell at Atari. He co-founded Atari, which was hugely successful, and he became a name people recognised in tech circles. But he’s not a household name like Jobs or Gates. And Atari was consumer electronics – games, which are fun and visible and talked about. Word processors are boring. Even if I’d had a major corporate partner, even if it had been marketed to consumers, it would still have been a tool for work, not entertainment.

The invisibility I’m talking about isn’t just about the B2B versus consumer distinction, though that matters. It’s about the kind of work the product supports. Games are exciting. Personal computers that let you program or create art – that’s exciting. But a machine that lets you edit documents more easily? That’s useful. It’s important. But it’s not thrilling in the way that captures public imagination.

There’s also the question of credit and visibility. If RCA had manufactured the machines, the credit would have gone to RCA. “RCA’s word processor” sounds very different from “Evelyn Berezin’s word processor.” The corporation would have owned the narrative. They would have owned the patents. They would have owned the brand. I might have gotten royalties or consulting fees, but I wouldn’t have become the inventor the way I did – or rather, the way I might have become if things had gone differently.

Look at what happened to Steve Wozniak. He designed the Apple II, and Apple marketed it brilliantly, and now Wozniak is famous. But that’s partly because Apple was his company. He was front and centre. If he’d designed the computer and then sold the design to an existing manufacturer, he’d be invisible. He’d be a footnote in the Apple story, if that.

So no, I don’t think the consumer market would have made me famous. The erasure wasn’t entirely about B2B versus consumer, though that’s part of it. It was about the kind of work – office work, secretarial work, the kind associated with women – being devalued regardless of the market. And it was about my company being acquired and absorbed into a larger corporation that didn’t care about preserving the founder’s name.

The sad irony is this: if I’d been a man in 1969, if I’d founded Redactron and it had failed spectacularly or succeeded wildly, people would have written about it. There would have been magazine articles. I would have become a name in tech entrepreneurship. But I was a woman, so the story got filed away. And by the time people started asking “Who built the word processor?” it was too late. The narrative had already been written without me in it.

Would a consumer market have changed that? Maybe slightly. There would have been more visibility. But I suspect the same erasure would have happened regardless. The technology that liberated secretaries from retyping didn’t confer glory on its inventor. It just became a tool that “existed,” and tools don’t have authors – they just have manufacturers.

That’s what I’ve come to understand. It’s not the market. It’s the kind of innovation. Innovation that solves a practical problem for workers gets less recognition than innovation that creates entirely new possibilities or builds foundational systems. That’s a cultural bias, not a technological one.

And it persists whether you’re selling to businesses or consumers.

Zainab Alami, Casablanca, Morocco | Systems Thinker & Technology Policy Advocate (Age 41)

You designed the Data Secretary by observing secretaries struggling with retyping. That’s held up as an example of user-centred design. But I’m wondering: did you ever consider whether the real problem was that secretaries were doing work that shouldn’t exist? That the document-heavy, revision-heavy systems they worked in were fundamentally inefficient?

In other words, you solved the pain point without questioning the system that created it. The secretary could now edit documents more easily – but she was still a secretary, still doing secretarial work, still paid less than the engineer who designed her tool. Did that tension ever occur to you? And do you think there’s a difference between designing for a user’s immediate need versus designing to transform the structural position that user occupies?

Zainab, you’ve asked the question that makes me most uncomfortable, which means it’s the most important question.

Yes, that tension occurred to me. And yes, I designed around the pain point without questioning the system that created it. I’m not going to pretend otherwise or dress it up as something more noble than it was.

Let me be honest about my thinking at the time. I was watching secretaries retype entire documents because someone wanted to change a word or fix a typo. The inefficiency was staggering. From an engineering perspective, it was obvious: there’s a problem, here’s a solution. Let me build the solution.

But I was also – and I need to say this plainly – thinking about a market opportunity. Secretaries were a huge, captive market. There were hundreds of thousands of them. They had budgets. Their employers wanted them to be productive. Here was a machine that would make them dramatically more productive. I could sell it.

Did I think, “Maybe the real problem is that we’ve organised office work in a way that requires endless document revision, and perhaps we should reorganise office work instead”? No. That would have been absurd from a business perspective. That would have been naive about how organisations actually function. You don’t get to reorganise how a law firm operates because you’ve invented a new tool. You build the tool and let it fit into the existing structure.

But you’re right that there’s something uncomfortable about that. I solved the secretary’s immediate problem – retyping – without addressing the structural problem – why is a secretary doing this work at all, and why is it valued so little?

Here’s what I would say in my defence, and then I’ll acknowledge the limits of that defence:

The immediate problem was real and was worth solving. A secretary spending two hours retyping a ten-page document because the boss changed his mind about the third paragraph – that’s wasted human effort. That’s demoralising work. If I could eliminate that, I should eliminate it, even if I wasn’t simultaneously revolutionising the entire structure of office labour.

You can’t wait for the perfect systemic solution before you solve the immediate problem. That’s paralysis. That’s letting people suffer while you wait for utopia. The Data Secretary made secretaries’ working lives better. Not perfect. Better. That matters.

But – and this is the important “but” – I was also complicit in keeping the structure intact. The tool I built made secretaries more efficient, which meant their employers could extract more work from them without hiring more people. The secretary could now produce four documents a day instead of two, so the organisation didn’t need to hire an additional secretary. The productivity gain went to the employer, not to the secretary.

If I had been thinking structurally, I might have designed the system differently. I might have built it in a way that democratised document creation – made it easy enough that anyone in the organisation could produce their own documents without needing a secretary. That would have been genuinely transformative. It would have questioned the existence of the secretarial role rather than just making the role more efficient.

And in fact, that’s what did happen eventually, but not because of my design. It happened because personal computers became cheap and ubiquitous, and then word processing software became cheap and ubiquitous. Suddenly, a manager could write his own memo. A lawyer could draft her own brief. The secretarial function didn’t disappear, but it changed. It became less about typing and more about organisation, scheduling, document management – higher-value work.

But that transition was painful for secretaries. The skills they’d spent years developing – typing speed, formatting, understanding document conventions – became less valuable. The jobs that required those skills evaporated or were downgraded.

So here’s my uncomfortable realisation: if I had designed the Data Secretary to be more democratic, if I had made it something that anyone in an office could use instead of a tool for professional typists, I might have accelerated that transition. I might have eliminated secretarial jobs faster. Would that have been better or worse?

I genuinely don’t know.

What I do know is that I didn’t think in those terms. I thought, “Here’s a tool for secretaries.” I didn’t think, “How does this tool change the entire structure of office work?” I didn’t think, “What does this mean for secretarial employment five or ten years from now?” I was focused on solving a technical problem and building a product that people would buy.

That’s a limitation, and I acknowledge it. But I also think it’s worth asking: is it the responsibility of an inventor to think about the systemic consequences of her invention? Or is that the responsibility of organisations, policymakers, and society more broadly?

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this. And I think the answer is: it’s everyone’s responsibility, not just the inventor’s. But inventors have a particular responsibility because we’re the ones who see the problem first and decide whether and how to solve it.

If I could go back, would I have done things differently? I honestly don’t know. I might have spent time thinking about how to make the technology more democratic, more accessible, less dependent on a specialised class of typists. But I also might have come to the same conclusion – that the immediate problem of retyping is worth solving on its own terms, separate from questions about the future of secretarial work.

What I would have done, I think, is acknowledge the tension. I would have been explicit about what the Data Secretary could and couldn’t do. It could make secretaries more productive. It couldn’t transform the fact that secretarial work was undervalued. It couldn’t equip secretaries with the skills they’d need as the profession evolved. It couldn’t guarantee them job security or better pay.

I could have designed it better if I’d understood the structural context more deeply. I could have built in features that made it easier for non-secretaries to use, for instance. I could have designed the user interface in a way that was less dependent on typing expertise. Those are concrete things I could have done differently.

But the bigger question – should I have refused to solve the immediate problem until the structural problem was solved – that’s not a question I can answer definitively. It feels like asking someone not to give medicine to a patient because the patient’s poverty and lack of healthcare access are the real problem.

You’re asking something important, though. You’re asking engineers to think not just about the problem in front of us but about the system that created the problem in the first place. That’s good. That’s necessary. And I wasn’t thinking that way in 1969.

Maybe engineers today can do better than I did.

Reflection

Evelyn Berezin passed away on 8th December 2018 at the age of 93, leaving behind a legacy that has only begun to be properly understood in the years since her death. This conversation, imagined seven years later, attempts to recover not just the facts of her life but the reasoning, the doubt, the pragmatism, and the occasional frustration that animated her five decades in computing.

What strikes most forcefully in reviewing her responses is how consistently she resists mythologising her own work. She was not a visionary in the romantic sense – she did not dream of transforming the world and then realise her dreams. She was a problem-solver who noticed inefficiency and built systems to address it. Airlines couldn’t manage reservations at scale; she designed a system that could. Secretaries spent hours retyping documents; she invented a machine that eliminated that drudgery. This is not the narrative of computing history that dominates popular imagination, which tends to privilege the founders of empires and the architects of theoretical breakthroughs. Yet it is perhaps the more honest account of how technology actually enters the world.

One significant divergence from the official record emerges in her account of her own ambitions around the Data Secretary. The standard narrative positions her as an entrepreneur with a singular vision – to commercialise the word processor and build a company around it. But in these responses, particularly to Zainab Alami’s question, she reveals a more conflicted perspective. She acknowledges that she was solving an immediate problem without interrogating the structural inequality that made that problem exist in the first place. She was not blind to this tension; she simply chose to prioritise the immediate gain over systemic transformation. That choice – pragmatic, businesslike, and also limiting – tells us something important about how innovation actually works in capitalist contexts, and it complicates any simple narrative of her as a liberation figure.

There are gaps in the historical record that deserve acknowledgment. The exact specifications of some of the custom chips Redactron designed remain undocumented in publicly available sources. The decision-making process at Teleregister about adopting transistor technology over vacuum tubes involved conversations and technical debates that were never formally recorded. Her thinking about the Reservisor’s architectural choices – why three processors rather than two, why specific redundancy patterns were chosen – survives only in fragments. Oral histories like her 2014 conversation with the Computer History Museum are invaluable precisely because they capture reasoning that would otherwise be lost. Yet even these cannot fully recover the technical knowledge that existed in her mind and the minds of her colleagues.

The historical record also contains some contestation about priorities and firsts. IBM’s contributions to word processing, Wang’s innovations, the evolution of dedicated systems versus general-purpose computing – these stories are told differently depending on the source. Berezin’s consistent position is not to diminish others’ achievements but to insist that she was there first with specific technologies and that the erasure reflects not technical inferiority but historical invisibility rooted in gender and the nature of her work.

Today, her influence is observable in unexpected places. The principles of real-time computing that she established for the Reservisor remain foundational to systems that handle billions of transactions daily – financial systems, airline reservations, emergency response networks. These systems are not “based on” her work in any direct lineage, but they follow architectural principles she proved could work at scale. Similarly, the user-centred design approach that she practised – observing what users actually needed rather than building what engineers thought they should want – has become almost commonplace in software development, though her specific contribution to establishing this practice is rarely cited.

The re-emergence of specialised silicon for machine learning and artificial intelligence validates, retrospectively, her intuition about custom hardware. The TPUs and custom AI accelerators that Freya Lindgren asked about represent a return to the kind of optimisation Berezin pursued – building hardware specifically for a computational workload rather than forcing all workloads onto general-purpose processors. In this sense, the technological pendulum has swung back toward her approach, even as the business models and manufacturing processes have evolved beyond anything she could have anticipated.