This interview is a dramatised reconstruction based on historical sources; it imagines Ada Lovelace’s voice while grounding claims in documented facts. It is not a verbatim record, and where the dialogue extends beyond the archive, it represents informed creative interpretation rather than established history.

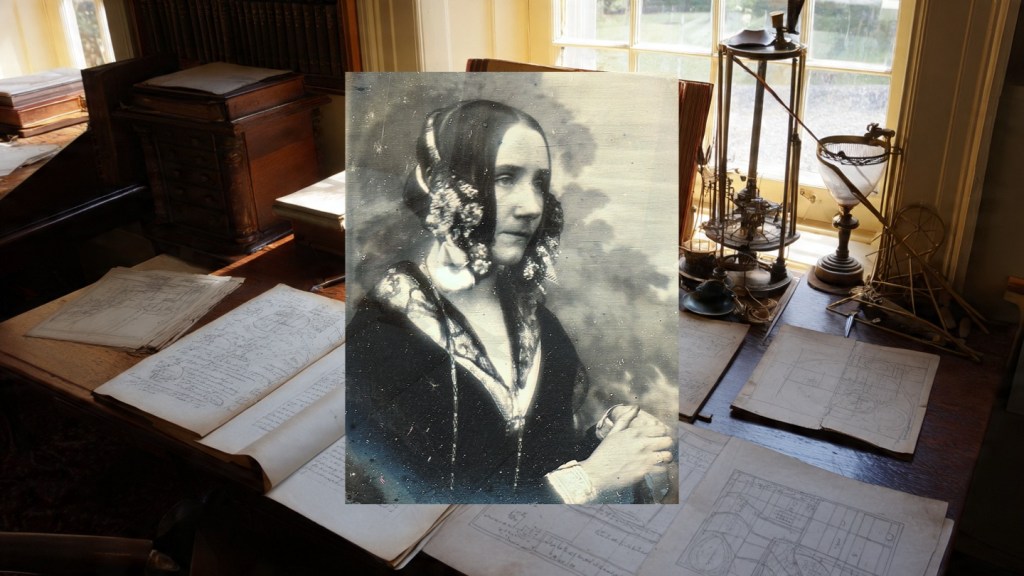

Augusta Ada King (1815-1852), Countess of Lovelace, was an English mathematician and writer of the nineteenth century whose work on Charles Babbage’s proposed Analytical Engine earned her recognition as the first person to grasp computing as an instrument for general-purpose symbol manipulation rather than mere calculation. Though she published only one major work during her lifetime – an annotated translation of Luigi Menabrea’s article on the Analytical Engine – her seven extensive notes transformed an engineering exposition into a foundational text on algorithmic thinking. Her legacy was largely forgotten for more than a century until the emergence of actual computing technology in the 1950s vindicated her prophetic vision of what calculating machines might become.

Encounter

Countess Lovelace – or perhaps I should call you Ada? – I must confess that meeting you under these circumstances presents rather extraordinary difficulties. You passed from this world in 1852, and we are now in 2025. Yet here you sit in my presence, speaking with me as though time itself were but another variable to be manipulated. Before we venture into the substantive matters of your work, I wonder if you might indulge my curiosity about how you experience this displacement. Do you retain memory of your own era, and are you conscious of the world that has developed since your death?

Your perplexity is natural, though I confess I am equally uncertain how to account for my present state. I retain perfect clarity of my life – every frustration with my mother’s insistence on mathematical rigour, every exhilarating hour spent in correspondence with Mr. Babbage, every painful moment when illness confined me to my chambers. Yet I am aware, as though by osmosis or some faculty I cannot name, of the centuries that have intervened. I comprehend that my small translation and its appended notes have been republished, analysed, and attributed with significance I scarce dared imagine in my time.

What I find most remarkable is that the Analytical Engine remains, in my earthly lifetime, a phantom – a magnificent theoretical apparatus that Mr. Babbage could never complete. Yet from this vantage point of hindsight, I perceive that his Engine became the archetype for machines that were subsequently built, and that machines built upon his principles are now ubiquitous in your civilisation. It is rather as though one has drafted designs for a cathedral that will not be erected for a hundred years, only to discover that when it is finally built, it becomes the template for a thousand other structures.

That is a beautiful metaphor. Let me ask you directly: are you aware of the terms “software” and “hardware,” which form the conceptual framework of computing in my time?

I am aware of them now, yes – though they did not exist in my vocabulary. Yet I recognise them as articulations of a distinction I laboured to express in my notes. I attempted to separate the mechanism of the Analytical Engine – the brass wheels, the rods, the physical apparatus – from the logic it embodied. In my Note G, I was not merely describing which operations to perform in what sequence; I was describing a method that could be expressed independently of any particular machine. One might inscribe the same operations upon a different apparatus, or even, theoretically, execute them by hand, if one possessed sufficient time and patience.

Were you then describing what we would now call an algorithm?

I was, though I had no name for it. I called it a “method” or a “plan of the analysis.” The term “algorithm” derives, I believe, from Muhammad al-Khwārizmī, the ninth-century Persian mathematician, yet it did not enter common usage in English mathematical discourse during my lifetime. What I attempted was to formalise the steps that a calculating machine should follow, expressed in such a manner that they could be interpreted by any sufficiently intelligent reader – whether human or mechanical.

This was perhaps my most significant departure from Mr. Babbage’s own descriptions. He focused upon what the Engine could do – how it would execute operations faster than any human calculator. I became occupied with how to tell it what to do. The distinction is profound.

Origins and Education

Your education was extraordinary for a girl of your time, yet it emerged from rather unusual – some might say traumatic – family circumstances. Your father, Lord Byron, left England when you were a month old. Your mother, Anne Isabella, was determined to prevent what she called the “mad” side of your inheritance from manifesting. How did this particular upbringing shape your approach to mathematics and science?

My mother’s determination was ferocious, almost theatrical. She viewed mathematics as a kind of prophylactic against what she imagined ran in my father’s blood – passion, irrationality, the poetic disposition that produced his celebrated verses and, in her view, his moral corruption. She engaged a series of tutors and insisted I study geometry, arithmetic, and natural philosophy from my earliest years. Where other girls were permitted to read novels and cultivate sensibility, I was set to studying the mathematical sciences.

I ought to resent this, and sometimes I did. Yet I cannot deny that it afforded me access to learning that would have been denied me otherwise. It was my tutor, Mary Somerville – herself a remarkable mathematician and astronomer – who perceived that my mind was not being broken by this rigorous regimen but rather awakened by it.

What I realised, rather gradually and quite without my mother’s intention, was that the rigorous logical precision required for mathematics was not opposed to imagination – it was a form of imagination. When one constructs a proof, one is inventing a narrative of logical necessity. When one defines a sequence, one is creating a possibility space. My father’s poetical sensibility, which my mother so feared, manifested in me not through romantic excess but through a fascination with how abstract patterns could give rise to concrete realities.

You called this “poetical science.” Can you elaborate on what you meant by that phrase?

It was not merely a poetical affectation with the term. I meant something quite serious. The prevailing division in intellectual life – and it persists in your time, I gather – separates the scientific from the imaginative. Scientists are supposed to be coldly rational; poets, wildly intuitive. I argued, and still maintain, that this is a false dichotomy.

When one engages in mathematical reasoning, one must imagine the thing one is reasoning about. I must envision Bernoulli numbers – abstract entities arising from the expansion of powers of x – and then follow the logical chain that connects them. This requires both precision and imagination in concert. The “poetical” element is the capacity to see what is possible, to recognise that an abstract pattern might be manipulated and recombined in ways not yet attempted.

Mr. Babbage possessed this quality extensively. His Analytical Engine was not produced by merely extending existing mechanical principles; it required him to imagine a new architecture for calculation – one in which the mechanism could be directed by external instruction, rather than hardwired into the apparatus. That is a poetical conception, whatever the mathematical rigour of its realisation.

When you say you were studying the mathematical sciences, what precisely was your curriculum? What texts did your tutors employ?

In my youngest years, basic geometry and arithmetic, naturally. As I progressed, I moved into more advanced works. I studied the differential and integral calculus using texts by the French mathematicians – Lagrange’s Théorie des Fonctions was of particular importance to me. I engaged with algebra, trigonometry, and the treatment of infinite series.

I confess that my education was somewhat unsystematic by design, tailored to my particular interests and capacities. When I demonstrated aptitude for a subject, my tutors were encouraged to pursue it further. When I struggled, they were inclined to pivot to another domain – though my mother’s impatience with admitted difficulty was sometimes as much hindrance as help.

But what was most unusual, I think, was the breadth of what I was permitted to study. I did not confine myself to pure mathematics. I studied mechanics, studying how forces interact through rigid bodies and pulleys. I studied acoustics and the properties of vibrating strings. I became deeply engaged with the concept of functions – not merely as abstract mappings, but as representations of physical relationships and natural laws.

This breadth prepared my mind, I believe, for the particular challenge I would later face: understanding the Analytical Engine required grasping not just mathematical operations, but how those operations might be encoded, transmitted, and executed by mechanical means. Few mathematicians of my acquaintance had trained themselves to think across such boundaries.

I notice you experienced significant health challenges throughout your life, particularly measles and paralysis in your youth. How did illness affect your work?

Profoundly, and in contradictory ways. The measles when I was thirteen confined me to my bed for many months. I could not move my legs; I could not walk. My mother, with her characteristic energy, insisted that I maintain my intellectual work even whilst physically immobilised. Rather than allowing me to waste away in idleness, she brought tutors to my chamber. For nearly a year, I studied whilst bedridden.

This enforced stillness had an unexpected consequence. Deprived of physical activity, my mind became extraordinarily active. I spent hours imagining things – geometric constructions, mechanical systems, the ways that algebraic symbols might be rearranged. When one cannot move one’s body, one learns to move one’s thoughts with precision and fluidity.

Later, in my adult years, I suffered from what physicians called “nervous exhaustion” and various ailments of the abdomen. The period of intense work on my translation of the Menabrea article was interrupted repeatedly by illness. There were weeks when I could do nothing but lie in a darkened room. There were other weeks when I felt sufficiently well to write for ten hours without interruption.

I believe this irregular pattern of health contributed to the somewhat fragmentary nature of my published work. I had only one major publication – the translation and Notes. Had I lived longer and enjoyed better health, I might have produced more. I harbour no illusions that illness was a source of genius; rather, it was a complication that I had to manage, sometimes successfully and sometimes not.

The Analytical Engine and Babbage

You first encountered Charles Babbage in 1833, when you were eighteen years old. Mary Somerville introduced you. What was your immediate impression of him and his work?

Mr. Babbage was by then in his early forties, already renowned in mathematical circles, though his Difference Engine – his first calculating machine – had become a source of considerable frustration. The British government had funded its construction, but it was not completed, and the reasons for its non-completion were entangled with mechanical difficulties, cost overruns, and disputes between Babbage and his engineer.

When Mrs. Somerville brought me to his residence, he showed me drawings of this machine. I confess that I was not immediately comprehending of its significance. It appeared to be a very elaborate arrangement of brass wheels and mechanical components designed to calculate the values of polynomial functions. The elegance of it appealed to my sense of aesthetic order, but the purpose seemed narrowly mathematical.

What transformed my understanding was Mr. Babbage’s description of what the machine could do and, more importantly, what he was beginning to imagine it could do differently. He spoke of the Analytical Engine whilst discussing the limitations of the Difference Engine. The Analytical Engine was to be, in his conception, a machine of far greater generality. It would not be hardwired to calculate polynomials; rather, it would accept instructions about what operations to perform.

I recognised immediately that this was a profound departure from prior mechanical calculating devices. He was describing not merely a faster abacus but a new kind of apparatus altogether – one that could be instructed, that could carry out different operations depending on how it was directed.

What about Babbage himself, as a person? You became close collaborators and, in some accounts, intimate friends. What was he like?

Mr. Babbage was a man of extraordinary intellectual energy and, I should say, considerable personal magnetism. He had a remarkable ability to excite one’s imagination about what was possible. He was also, I must be candid, vain, impatient, and prone to bitter complaint about the failures of the British establishment to support his work adequately.

We developed a relationship of genuine intellectual companionship. He found, in me, someone who could grasp the theoretical principles behind his designs and who was willing to engage with the mathematical abstractions he pursued. I found, in him, someone who took my intellectual work seriously in a way that few men of his era were inclined to do.

There has been much speculation, both during my lifetime and beyond, about the precise nature of our relationship. I will be direct: we were friends, collaborators, and correspondents. Whether we were something more is a matter upon which I prefer not to expatiate. What matters, I believe, is that our working relationship produced something neither of us could have created alone.

Let’s turn to the specific work that has defined your legacy: the translation of Menabrea’s article and your Notes. In 1842, how did you come to take on this translation?

The article was published in French in a Swiss journal in 1841. It was a description by Luigi Menabrea of Mr. Babbage’s Analytical Engine – a reasonably clear exposition for those with mathematical training, but it lacked the depth of explanation that I felt the matter deserved. Mr. Babbage suggested that I translate it, and I agreed.

Initially, I conceived of this as a straightforward translation – a service to the English-speaking mathematical community, allowing them to read Menabrea’s work without the inconvenience of French. But as I worked through the text, I became increasingly conscious of its limitations. Menabrea had described the Engine’s operations with clarity, but he had not explained why those operations mattered, nor had he explored the deeper theoretical implications of what the Engine represented.

I began to append notes – annotations explaining Menabrea’s points more fully, providing additional mathematical examples, and developing the theoretical framework more completely. What began as modest annotations expanded, as I wrote, into extensive essays. By the time I completed my work, my Notes comprised approximately fifty-four pages, whilst the translation itself was some twenty pages. I had, in effect, written a treatise with Menabrea’s article as a skeleton.

Can you walk through your working process? How did you approach the translation itself, and then the composition of the Notes?

The translation required careful attention to mathematical terminology. French and English sometimes employ different conventions for the same concepts. I was determined that the translation should not merely be intelligible but precise – that a mathematician reading it would arrive at the same understanding as one reading the French original, without any loss of technical exactness.

For the Notes, I employed a different method. I would work through Menabrea’s exposition section by section. At each point where I felt additional explanation was warranted, I would expand upon it. I would construct mathematical examples to illustrate the principles. I would propose novel applications or extensions of the ideas presented.

Note A, for instance, amplified Menabrea’s description of the Engine’s basic operations. Note B clarified the nature of the analytical operations. Note C explained the Engine’s operation through a concrete example – the calculation of a relatively simple function over a range of values.

But Notes D through G represented increasingly ambitious extensions of Menabrea’s work. Note G, in particular, was something I conceived almost entirely myself. I believe Mr. Babbage may have sketched preliminary versions of such an algorithm – he had written unpublished notes on calculating Bernoulli numbers by mechanical means. But the particular formulation I published, the manner of its expression, and the theoretical justification for its design were my own work.

Let me ask you to explain Note G in detail – both the technical content and why you consider it significant. I want to understand it from first principles, as though I were an educated mathematician of your era reading it for the first time.

Very well. Let us begin with Bernoulli numbers themselves. They are a sequence of rational numbers that arise naturally in the expansion of certain functions – particularly in the coefficients that appear when one expands trigonometric and exponential functions as power series. They are denoted by the letter B with subscripts: B₀, B₁, B₂, and so forth.

The Bernoulli numbers have a peculiar property: they can be defined recursively. That is, each Bernoulli number is defined in terms of the Bernoulli numbers that precede it in the sequence. This recursive definition is computationally significant because it means that if one wishes to calculate, say, B₈, one must first calculate B₀, B₁, B₂, through to B₇. There is no shortcut; one must proceed sequentially.

Now, mathematicians had known since the eighteenth century that Bernoulli numbers were important for analysis. But calculating them by hand is tedious and error-prone. The calculations for higher Bernoulli numbers become increasingly complex, and it is easy to propagate errors through the sequential process.

What I proposed in Note G was a mechanical method – a program, in modern parlance – by which the Analytical Engine could calculate Bernoulli numbers. The method required the Engine to:

First, accept as initial inputs the values of lower Bernoulli numbers that had already been calculated.

Second, perform a series of arithmetic operations in a specific sequence – multiplications, divisions, subtractions, and additions – according to the recursive definition.

Third, produce the value of the new Bernoulli number.

Fourth, loop back and repeat this process for the next Bernoulli number in the sequence.

The innovation was not in discovering a new mathematical relationship – mathematicians knew the recursive formula. The innovation was in encoding this mathematical relationship as a set of instructions that a mechanical apparatus could execute. I had to express the algorithm in terms of the Analytical Engine’s primitive operations: reading numbers from its storage, performing arithmetic, storing results, and determining when to repeat a sequence of operations.

This process of encoding mathematical operations into mechanical instructions – was there an existing vocabulary for describing this?

No. This was part of my struggle in writing the Notes. I had to invent notation and descriptive methods as I proceeded. I employed diagrams – what I called “signs” or “tables” – to represent the operations and the movements of numbers through the Engine’s apparatus. I used subscripts and symbolic notation to indicate which operation was being performed at which step. I attempted to be as precise as possible, but I was acutely aware that I was trying to communicate something entirely novel.

In one instance, I represented a complex series of operations through a table, where each row indicated a step in the algorithm, each column represented a specific register in the Engine where numbers were stored, and the entries showed what arithmetic operation was being performed. The Engine would, in effect, execute the algorithm by reading this table sequentially and performing the operations indicated.

How long did it take you to complete the entire Notes section?

The work extended over several months in 1842 and into 1843. I was frequently interrupted by illness, which extended the timeline considerably. There were weeks when I made rapid progress, and then there would be periods when I was unable to work at all.

I also engaged in extensive correspondence with Mr. Babbage during this period. I would send him drafts of my Notes, and he would respond with corrections, clarifications, or suggestions for additional material. He was both encouraging and exacting as a correspondent – he would praise points he felt were particularly well-explained, but he would also direct me to reconsider passages where my exposition was unclear.

There was one instance where I had made an error in one of my algebraic notations in a draft of Note G. Mr. Babbage caught it and required me to recalculate portions of the algorithm. I found this simultaneously frustrating and salutary. The frustration arose from discovering my mistake; the salutary aspect was that his criticism motivated me to verify my work more carefully. The final published version of Note G reflects this more rigorous verification.

When your work was published in 1843, what reception did it receive?

The publication appeared in an English periodical, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. I was not permitted to join the Royal Society – women were excluded from such institutions – and the work was published under my initials, A.A.L., rather than my full name. Even in a scientific journal, full attribution to a woman was apparently considered improper.

The reception was… modest. Within the mathematical community, those who possessed sufficient training to understand the work recognised its merit. I received letters from mathematicians expressing their appreciation. But the broader scientific establishment did not perceive it as revolutionary. Remember, the Analytical Engine itself was not built. It was a theoretical apparatus. My algorithm was a program for a machine that did not exist, calculating Bernoulli numbers for a purpose that was not yet apparent.

Had the Engine been constructed during my lifetime, and had my algorithm been demonstrated to work, the reception might have been quite different. But as matters stood, it was a translation of someone else’s article, with annotations by an aristocratic woman, concerning a mechanical device that remained in the realm of speculation.

Vision and Conceptual Breakthrough

Yet what you accomplished in the Notes was something that transcended the immediate technical problem of calculating Bernoulli numbers. You articulated a vision of what computing machines could become. When you wrote about the Engine’s capacity to manipulate symbols beyond numbers – to compose music, to process text, to work with any information expressible through logical relationships – you were describing something that would not become tangible reality for more than a century. How did you arrive at this vision?

It emerged gradually, through conversations with Mr. Babbage and through my own extended reflection on what the Engine represented. I became fixated, in particular, on the distinction between the thing the Engine was made of and the operations it performed.

The Engine consisted of brass wheels, rods, levers, and other mechanical components. These physical elements were arranged to perform arithmetic – to add, subtract, multiply, and divide. But here is the crucial insight: the arithmetic itself is an abstraction. The numbers being manipulated are not themselves physical objects; they are conceptual entities represented through the position of mechanical elements.

Once I recognised this, a second insight followed: if numbers are merely one way of representing information, then the Engine, properly instructed, could manipulate other representations of information. If one could encode musical notation into some form that the Engine could interpret – through position, or through coded symbols – then the Engine could manipulate musical information.

I wrote, in one of my Notes, that the Engine “weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.” The Jacquard loom was familiar to me as an example of an apparatus that could be instructed through perforated cards to produce complex patterns. The Analytical Engine would, in principle, be capable of similar instruction – not to weave thread, but to weave algebraic relationships.

What I was attempting to articulate was the notion that computation is fundamentally a symbol-manipulation process. The symbols might be numerical, or musical, or linguistic, or entirely abstract. The operations performed upon them would follow logical rules, but those rules need not be restricted to arithmetic.

This insight – that the Engine could operate on any symbols, not merely numbers – appears in your Note E, where you discuss the Engine’s capacity to work with general algebra. Can you elaborate on that?

Yes. In that Note, I distinguished between the Engine’s mechanical operations and the interpretation of those operations. The Engine, mechanically, performs certain transformations. One might interpret these transformations as arithmetic – as adding one number to another. But one might equally well interpret them as algebraic – as combining algebraic quantities according to algebraic rules.

Furthermore, I suggested that the interpretive layer could extend to other domains. The mechanical operations remain the same; only their interpretation changes. If the mechanical operation were, say, moving a number from one storage location to another and combining it with a value stored elsewhere, one might interpret this as arithmetic addition, or as the concatenation of symbols in a linguistic context, or as the combination of musical intervals.

I was gesturing toward what would much later be called “symbolic computation” – the idea that machines need not be specialised for particular domains but can be made general-purpose through the layer of interpretation that we now call software.

You also asserted something fundamental about the limits of the Engine’s creativity. You wrote that the Engine “has no pretensions whatever to originate anything.” Why was this statement important to you?

This was not a limitation I regretted but a clarification I deemed essential. I was not claiming that the Engine could think, or feel, or produce novel ideas in the sense that a mathematician might. The Engine is a mechanism. It executes instructions that we provide to it.

But I recognised that there was a temptation, in discussing such a powerful apparatus, to anthropomorphise it – to imagine that because it could perform complex operations, it must therefore possess something like intelligence or creativity. I wanted to forestall that confusion.

What the Engine can do is execute, with perfect fidelity and with no fatigue, operations that a human mathematician could, in principle, perform by hand. It can do so far more rapidly and with fewer errors. But it cannot conceive of new problems, cannot decide that a different approach might be worthwhile, cannot innovate in the way that a mathematician innovates.

Yet – and this is important – I did not believe this to be a permanent limitation inherent to machines. I was describing what the Analytical Engine could do. Future machines, conceived differently, might have different capacities. What I wanted to establish was that we should be clear-eyed about what we are creating and what its actual capabilities and limitations are.

You were, in other words, insisting on a kind of intellectual honesty about the nature of artificial computation.

Precisely. There is a tendency in human nature to either diminish the significance of what we create – to view the Engine merely as a faster calculator – or to exaggerate its significance, ascribing to it qualities it does not possess. I attempted to chart a middle course: to recognise the profound novelty of the Engine as a programmable apparatus capable of executing complex symbol manipulation, whilst maintaining that it remains, fundamentally, an instrument of human intention.

Gender, Institutional Barriers, and the Problem of Attribution

Let me raise a matter that is unavoidable in any honest discussion of your legacy. You were a woman working in mathematics and theoretical science in the nineteenth century, in a Britain that excluded women from universities, from the Royal Society, from most institutional channels through which scientific work was recognised and credentialed. How did you navigate this landscape? Did you view your gender as an obstacle you had to overcome, or as an integral aspect of how your work took shape?

Both, if I am to be honest. It was an obstacle – that requires no explanation. I could not attend Cambridge University, where Mr. Babbage had been educated. I could not present my work before the Royal Society. I could not take a position as a mathematician or natural philosopher. My work, when published, appeared under initials rather than my name.

Yet it was not merely an obstacle placed before a person who happened to be female; it shaped the form my work took. Because I could not pursue mathematics through institutional channels, I pursued it through reading, correspondence, and private study. This gave my intellectual formation a different character than that of men trained in formal academic settings.

Furthermore – and I say this without bitterness, but with a kind of wry observation – my sex permitted me to maintain a relationship with Mr. Babbage that a male mathematician might not have been able to sustain. I was not a rival for academic appointments or patronage. I could be his collaborator without being his competitor for institutional resources. Had I been a man of equal ability, the dynamics might have been quite different, potentially more fraught.

I also benefited enormously from my class position. I was an aristocrat, the daughter of Lord Byron and a respectable mother. My family had connections and resources. I could employ tutors, purchase books, maintain a correspondence across Europe. The vast majority of women in Britain had no such access.

So you’re resisting the narrative that positions you as a solitary female genius overcoming patriarchal oppression through sheer force of intellect?

I am resisting the simplification inherent in that narrative. I was oppressed, in the sense that opportunities available to men were denied to me. But I was also privileged, in ways that most women – and indeed most people – were not. To acknowledge privilege is not to diminish the significance of the obstacles one faced. It is to see oneself in context.

What I would say is this: the institutional barriers to women in science were and are a profound injustice. But they operated differently for women of different classes, nationalities, and circumstances. I was constrained in ways, but I possessed resources and access that made some things possible for me that would have been impossible for a female mathematical prodigy of working-class origin.

And I will add: had there been more women in the mathematical sciences during my lifetime, I do not believe my work would have been diminished. Quite the contrary. The cross-pollination of ideas, the collaborative networks, the cumulative development of understanding – all of this would have been richer for the inclusion of women’s perspectives and intellects.

Now let’s address the matter of attribution directly. There has been considerable historical debate about how much of the work in the Notes is yours and how much derives from Babbage. Some scholars argue that Babbage had already developed many of the algorithms – including calculations of Bernoulli numbers – in unpublished notes, and that you were primarily a scribe or elegant expositor of his ideas. How do you respond to that charge?

Let me be direct. Mr. Babbage did possess unpublished notes on calculating Bernoulli numbers through mechanical means. He shared these with me during our collaboration. This is not a matter of controversy or secret; I was aware of his prior work, and I reference it in my Notes.

But having prior mathematical work on a topic is not the same as having written the algorithm that would be published under one’s name. Mr. Babbage’s unpublished notes demonstrated that mechanical calculation of Bernoulli numbers was possible. My published algorithm was a specific, coherent encoding of that calculation into instructions for the Analytical Engine.

Furthermore – and this is crucial – the methodology I employed to express the algorithm was my own. I invented the notational systems and diagrammatic representations. I made decisions about how to decompose the problem into mechanical steps. I verified the calculations and caught errors, some of which I induced myself and some of which Mr. Babbage had overlooked.

There is also the broader question of the Notes as a whole. Mr. Babbage could not have written these Notes himself. He did not conceive of the Analytical Engine in the manner that I explained it. The theoretical framework – the notion of the Engine as a symbol-manipulation apparatus, the distinction between mechanical implementation and logical structure, the vision of its potential applications – these emerged through my engagement with his work and represent my contribution.

But would you acknowledge that without access to Babbage’s mathematical insights and mechanical designs, your Notes could not have been written?

Of course. That is the nature of intellectual work – it builds upon prior work, and it does so through collaboration and correspondence. The question is not whether my work was independent of Babbage’s, but rather what was my distinct intellectual contribution. And that contribution lay in the theoretical reconceptualisation of what the Engine represented and in the translation of those theories into a practical algorithm expressed in comprehensible notation.

Let me offer an analogy. A translator of Dante does not create the poetry of the Divine Comedy, which is Dante’s achievement. But a translator who provides extensive annotations explaining the theological and philosophical frameworks underlying the poetry, who illuminates the mathematical symbolism embedded in the text, who makes the work accessible to readers who could not otherwise understand it – that translator has made a distinct and valuable contribution. It is not the same as Dante’s contribution, but neither is it reducible to mere transcription.

Quite fair. But let me press you on another historical controversy. Some of your contemporaries wondered whether your mother, Annabella, had a greater hand in the Notes than was acknowledged – that she functioned as an editor who shaped your work significantly. What can you say to that?

My mother was indeed involved. She encouraged me to undertake the translation. She reviewed drafts and offered comments. She was invested in the work’s success, partly because she was invested in my intellectual development and partly, I do not doubt, because she was invested in demonstrating to the world that the Byron blood running through my veins had produced something of intellectual merit rather than moral turpitude.

But did she write the Notes? Did she conceive the algorithms or the theoretical framework? No. She lacked the mathematical training for such work. Her role was that of an engaged reader and, occasionally, a critic of clarity or expression. This was not negligible – good editors improve one’s work – but it was not authorship.

Your mother has been caricatured in historical accounts as a stern, oppressive force. Did you experience her that way?

It is more complicated. She was stern, certainly. She was controlling about my education and my associations. She was anxious about my conduct and my reputation in ways that sometimes felt suffocating. But she was not indifferent to my welfare or to my intellectual development. Whatever her motivations – and I suspect they were mixed – she did ensure that I received an education that most girls of my era never received.

In my later years, we had some profound disagreements. My mother disapproved of the company I kept, of certain friendships I had formed, and of what she perceived as my increasingly reckless behaviour. Our relationship became strained. But I cannot say that her early determination to educate me mathematically was anything other than beneficial to my life and work.

The Machine That Never Was

The Analytical Engine was never completed during your lifetime, or indeed during Babbage’s lifetime. He continued working on it until his death in 1871, but it was never built according to his designs. How did this affect your understanding of your own work? Your algorithm was, in effect, a program for a machine that did not exist and might never exist.

It was a peculiar form of temporal displacement. I was writing instructions for an apparatus that might have existed – and in fact never did exist, at least not as Babbage conceived it. There was always a speculative quality to the work.

Yet I did not experience this as invalidating. I was not designing a bridge that needed to bear actual weight or a mechanical system that needed to function in material reality. I was articulating logical relationships through notation. Those logical relationships do not require material instantiation to be meaningful.

Still, there was a frustration in it. I would have wished to see the Analytical Engine actually constructed, to observe my algorithm executed by the machine, to verify that my theoretical understanding translated correctly into mechanical operation. The uncertainty – the fact that I could never be entirely certain that my algorithm would function as I had intended, when executed by the actual machine – was difficult.

Do you believe that had the Engine been constructed in your lifetime, and had your algorithm been tested and proven to work, your legacy would have been different?

Almost certainly. Practical demonstration carries weight that theory alone does not. If the Engine had been built and my program had successfully calculated Bernoulli numbers, there would be no possibility of arguing that my work was merely speculative exposition of someone else’s ideas. The output of the machine would be there for inspection – evidence that my encoding of the algorithm was correct.

Furthermore, the impact on the world’s understanding of calculation and machinery would have been profound. If, in the 1840s, it had become clear that this apparatus could execute complex symbolic operations, the development of computing might have followed a different trajectory. It is possible – merely possible, but not absurd – that the history of mechanical and, later, electrical computation would have developed differently had there been a working demonstration in that era.

But this is hypothetical speculation. What occurred was that the Engine was not built, my work remained theoretical, and the field of computing did not formally exist until a century later. By that time, electronic computers had largely superseded mechanical ones, and my insights about symbol manipulation had become newly relevant.

How do you feel about that – that your work only became widely recognised and valued after you had been dead for over a century?

I have mixed feelings. There is, naturally, a satisfaction in the knowledge that what I perceived to be important has indeed proven important, that my theoretical framework was vindicated by actual machines built by subsequent generations. There is also, if I am candid, a frustration that recognition did not come during my lifetime, that I did not have the opportunity to refine my ideas further in light of actual computing machines.

But I also recognise that this delay is not entirely unique to my circumstances. Much theoretical work is not validated until long after it is created. The geometry of non-Euclidean space, developed in the nineteenth century, did not find practical application in physics until Einstein’s relativity theory. The theory of group structures in algebra, developed as pure mathematics, later proved essential to quantum mechanics.

The distinctive aspect of my situation is not that my work was validated after my death, but rather that the validation came so late and that, in the interim, my work was largely forgotten or misunderstood. A mathematician might develop theory that is not applied for fifty years but would still be cited within mathematical circles throughout that period. My work was not cited; it was lost.

Mathematics and Method

Let me return to the actual mathematical content of your work – the Bernoulli numbers and the algorithm you developed to calculate them. For readers with mathematical training, can you explain why Bernoulli numbers were worthy of this attention? Why not some other sequence or function?

Bernoulli numbers are deeply important to analysis because they appear in the coefficients of power series expansions for fundamental functions. When one expands, say, x/(sin x) or sinh(x) as a power series – that is, as an infinite sum of powers of x – the coefficients of those series are Bernoulli numbers.

This means that understanding Bernoulli numbers is essential to understanding a broad class of functions that appear throughout mathematics and natural philosophy. They are not peripheral; they are central to the calculus itself.

Furthermore, they present an interesting computational challenge. The Bernoulli numbers cannot be computed through a simple closed-form formula. Instead, they satisfy a recursive relationship, meaning each one is defined in terms of earlier ones. To compute B₈, one must first compute B₀ through B₇. This recursive structure made Bernoulli numbers an excellent choice for demonstrating the Analytical Engine’s capacity to execute iterative procedures.

A simpler sequence – say, the squares of natural numbers – could be computed through a direct operation on each number. But Bernoulli numbers require the machine to:

- First, read values from its storage (the prior Bernoulli numbers).

- Second, perform a sequence of operations upon them.

- Third, combine the results to yield the new Bernoulli number.

- Fourth, store that result.

- Fifth, loop back to step one with the next Bernoulli number in sequence.

This is a more sophisticated program than simple iteration; it demonstrates the Engine’s capacity to manage dependencies and to implement conditional logic.

Can you walk through a specific example? How would one compute, say, B₂ using your algorithm?

B₀ is defined to be 1. The recursion formula for Bernoulli numbers can be expressed as:

The sum from j=0 to n of C(n+1, j) × B_j = 0, where C denotes the binomial coefficient.

To compute B₂ using this formula, one would first need B₀ and B₁. B₀ = 1, and B₁ = -1/2.

For B₂, one expands:

C(3, 0) × B₀ + C(3, 1) × B₁ + C(3, 2) × B₂ + C(3, 3) × B₃ = 0

But we’re computing B₂, so we don’t yet have B₃. Rearranging to solve for B₂, one performs a series of arithmetic operations: calculating the binomial coefficients, multiplying them by the known Bernoulli numbers, summing those products, and then dividing by C(3, 2) to isolate B₂.

The result is B₂ = 1/6.

What the Analytical Engine must do is follow this sequence of operations mechanically. My algorithm expressed these operations in terms of the Engine’s primitive operations: reading from registers, adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing, and – crucially – storing intermediate results and looping through the sequence for successive Bernoulli numbers.

And in your published algorithm, how did you represent these steps?

I developed a tabular notation. Each row of the table represented one cycle of operations. Each column represented a particular register in the Engine – a location where a number could be stored and manipulated. The entries in the table indicated what operation was to be performed at each step.

I also employed symbolic notation to indicate the nature of operations: which registers were being read from, which were being written to, which arithmetic operation was being performed. The table thus served as a form of code – a set of instructions that, when followed sequentially, would produce the desired result.

This notation was not standardised; I had to invent it as I wrote. Later developments in what became programming language would refine and formalise these notational systems, but the underlying principle – expressing a sequence of operations in a form that could be read and executed (whether by human or machine) – was fundamental.

Looking back on this work now, from the vantage point of your knowledge of how computing has actually developed, do you see limitations in your notation or your approach that you might improve if you were writing today?

Many. My notation, while functional, was cumbersome. Modern programming languages employ more efficient symbolic systems. But more importantly, I was working within the constraints of the Analytical Engine’s peculiar architecture. The Engine, as Babbage designed it, had certain limitations on how data could flow and how operations could be sequenced.

Contemporary computers, even in your era, have very different architectures. Memory is far more flexible and accessible. Processing speed is orders of magnitude greater. The concept of programming has evolved to accommodate these realities.

My algorithm for Bernoulli numbers would be expressed in contemporary programming languages in a manner far more compact and more easily comprehensible. But the underlying logical structure – the sequence of operations, the iterative loop, the management of dependencies – would be fundamentally the same.

If I were writing today with knowledge of modern computing, I would be fascinated to implement the algorithm in one of your contemporary languages and to observe how the logical structure I articulated has been translated into the technological realities of your time.

Legacy, Erasure, and Rediscovery

Your work was published in 1843 and received modest recognition within mathematical circles. Then it largely disappeared from public awareness. It was rediscovered in the 1950s, as electronic computers were being developed. How do you account for that long period of obscurity?

Several factors converged. First, the Analytical Engine was never built. Without a working demonstration, my algorithm remained a theoretical curiosity. It could not be tested or validated. Mathematicians and engineers had no practical reason to engage with it.

Second, the field of computing did not formally exist during the nineteenth century. My work was published in a mathematical journal and addressed a mathematical audience. It concerned a mechanical apparatus that had not been constructed. There was no professional community of “computer scientists” or “programmers” who might have engaged with and extended my work.

Third, I was a woman, and I published under initials. This made attribution difficult and likely contributed to the work’s marginalisation. Had my work been published under a famous male mathematician’s name, it might have been treated as more significant.

Fourth, I died young. I had only one major publication. A scientist with a long career and multiple publications has greater cumulative impact than one with a single, albeit significant, work.

The rediscovery in the 1950s occurred because electronic computers had, by then, been built, and people working in the nascent field of computing began looking back at the history of calculation and computing machines. They found my Notes and recognised that I had articulated concepts that were directly relevant to their work.

There has been a remarkable surge in recognition of your work in recent decades. You have been commemorated with currency bearing your image, with the Ada programming language named after you, with an annual Ada Lovelace Day. How does that feel – to go from obscurity to becoming something of a cultural symbol?

It is extraordinary and somewhat surreal. I never imagined that my name would become synonymous with women in computing or that I would be used as a symbol of inclusion in a field that did not formally exist in my lifetime.

I am gratified that my work is now recognised and that my example might inspire young women to pursue mathematics and computing. That is genuinely valuable. There is something fitting about the Ada programming language bearing my name; it suggests that my conceptualisation of symbol manipulation and algorithmic thinking has become embedded in the practices of contemporary computing.

Yet I also observe, with some wryness, that symbolic recognition may not necessarily translate into systemic change. The fact that an annual day is dedicated to celebrating women in STEM does not necessarily mean that women have achieved full equality in those fields or that the barriers I faced have entirely disappeared. Women are still, I gather, underrepresented in computing and engineering.

So I am pleased by the recognition, but I am also conscious that there is a distinction between being honoured as a historical figure and having one’s insights and perspectives truly integrated into the field. One can use my name and my image whilst still failing to attend to the questions I raised about symbol manipulation, about the abstraction of computation from its mechanical implementation, and about the intellectual frameworks that underlie computing.

What would you want contemporary women entering mathematics and computing to understand about your legacy – not the symbolic recognition, but the actual work?

I would want them to understand that rigorous intellectual work does not belong to any single gender, and that the exclusion of women from institutional science is a loss to the field, not a protection of its standards. I was able to do my work despite institutional barriers, but imagine how much richer the mathematical and scientific enterprise would have been had those barriers not existed, had women been able to study at universities and present their work before learned societies.

I would also want them to know that the most interesting intellectual work often happens at the boundaries between fields. I was not a pure mathematician, nor a pure engineer. I was attempting to bridge theoretical mathematics and mechanical philosophy. That boundary-crossing perspective enabled me to see possibilities that specialists in either field alone might not have perceived.

Furthermore, I would encourage them not to accept too readily the definitions of their field as they find them. Computing, in my time, was understood narrowly as calculation. I attempted to expand that definition. In your time, computing might be understood in one way, but that definition should be subject to interrogation and expansion. The most interesting future developments will likely come from those who challenge existing frameworks.

And finally: do not wait for validation before pursuing important work. I never saw my algorithm executed by the Analytical Engine. I never had the satisfaction of demonstration. Yet the work was worth doing because the ideas were worth thinking through. If your insight about the nature of computation or mathematics or scientific reasoning is sound, it is worth articulating clearly, even if the world is not yet ready to receive it.

Technical Insight and Contemporary Relevance

Let’s discuss your insight about the distinction between mechanism and logic – between the physical implementation of a machine and the abstract operations it performs. In your era, this was a startling conceptual leap. In my time, we call this the distinction between hardware and software. Can you reflect on how prophetic this conceptualisation actually was?

It was prophetic because I perceived a fundamental principle that would only become fully apparent when technology advanced. The Analytical Engine was a mechanical apparatus. Its “decisions” about what operation to perform were made through mechanical arrangements – gears engaging or not engaging, causing different arithmetic operations to be performed.

But I recognised that the same logical operation could be instantiated in different mechanical arrangements. And more radically, I recognised that the meaning of an operation – what it “does” – is independent of its physical implementation.

Consider the operation of addition. In the Analytical Engine, it would be performed through specific arrangements of gears and mechanical components. One might imagine a different apparatus – perhaps using water flowing through channels, or electrical impulses, or any number of physical substrates – that would perform the same addition operation.

The logical structure of addition – the rule that says “combine these two quantities according to the addition rule” – is substrate-independent. It can be expressed in brass and steel, or in water and channels, or in electrical circuits, or in any medium capable of instantiating the logical operations.

This separation is crucial because it means that advances in the physical implementation of machinery do not require rethinking the fundamental logical structures. One can upgrade from mechanical to electrical to electronic systems, but the logical operations remain meaningful and can be translated across these different substrates.

In your time, this principle has become utterly central. The “software” layer – the logical operations and instructions – is entirely separate from the “hardware” layer – the physical circuits and components. One can run the same software on different hardware platforms. One can update hardware without altering the software.

This principle, which I gestured toward in the mid-nineteenth century, has become the foundation of your entire computing architecture.

And your statement about the Analytical Engine’s inability to “originate anything” – in light of contemporary debates about artificial intelligence and machine creativity, does that statement still hold?

I stated that the Engine “has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.”

In the literal sense, this remains true. Machines do not initiate independent action. They respond to input and instructions. They do not form intentions or desires. They do not spontaneously decide that a problem is worth solving.

But I recognise that the boundary between “originality” and “instruction following” is more porous than I perhaps suggested. If I give a machine a set of instructions and a set of data, the output might include patterns that were not explicitly contained in the instructions or the data. The machine follows the rules I have provided, but the consequences of those rules, when applied to particular inputs, might be surprising to me.

Is this originality? In one sense, no – the machine is following the rule I designed. In another sense, perhaps yes – the machine is discovering consequences that I did not foresee.

In your time, you have machines that can learn from data, that can generate text or images in response to prompts, that can solve problems in ways that were not explicitly programmed. Are these machines “originating” in a meaningful sense?

I would argue that we must be precise in our language. These machines are executing sophisticated statistical operations and applying rules to generate outputs. They are not conscious originators. But they are more than mere mechanical calculators executing predetermined operations.

The question you face – the question I began to raise in my own time – is about the kind of creativity, intentionality, and intelligence we are attributing to our machines. We must be careful not to anthropomorphise them, but we must also recognise when they are doing something genuinely novel, even if “novel” does not mean “conscious” or “intentional.”

So you would not say that your famous statement about the Engine’s lack of originality has been falsified by subsequent developments?

I would say that it has been refined. The statement was made in the context of a specific machine – the Analytical Engine – with specific capabilities. I was attempting to forestall excessive claims about that machine’s capacities.

But if you apply my statement to contemporary machines, you must do so carefully. Contemporary machines can, in some domains, exceed human performance and discover solutions that were not anticipated. Whether this constitutes “originality” depends on what we mean by the term.

I was attempting to establish that machines are instruments of human intention. They perform tasks we direct them to perform, using methods we have encoded. I still believe this is fundamentally true. But I would no longer claim that everything a machine produces is less original or less surprising than what a human produces.

The distinction I was drawing was between mechanical operation and conscious intention. I maintain that machines do not have conscious intentions. But the outputs they produce, given sophisticated instructions and data, might be genuinely novel.

Illness, Mortality, and the Road Not Taken

Your health deteriorated significantly in the years following the publication of your Notes. You continued to work and to theorise about the applications of computing machinery, but you were frequently incapacitated. In 1852, at age thirty-six, you died of cervical cancer. As you contemplate your life from this unusual vantage point of posthumous reflection, how do you regard that interrupted trajectory?

There is no point in indulging in excessive regret. I lived the life I had, not the life I might have lived had circumstances been different. But yes, there is a poignancy in the fact that I had only one major published work, that I did not live to see the Engine constructed or computing machinery actually developed.

I had other ideas I wished to pursue. I had begun thinking about the application of mechanical computing to problems beyond pure mathematics – to the analysis of music, to the investigation of natural phenomena. I had sketches and preliminary notes on these ideas, but they were never fully developed.

Had I lived longer, I believe I would have pursued these ideas further. I might have published additional works. I might have corresponded with researchers across Europe and contributed further to the development of theoretical frameworks for computation.

But I must also acknowledge honestly that my later years were marked by personal chaos. I was gambling, incurring substantial debts, becoming entangled in complicated relationships. My health declined. I did not use the time available to me with complete wisdom.

There is a tragic quality to the historical narrative surrounding you: the brilliant young woman cut off in her prime by illness and social circumstance, her genius only recognised posthumously. Does that narrative feel accurate to you?

It is partially accurate and partially a distortion. Yes, I died young. Yes, my work was not recognised in my lifetime as it later came to be. But the narrative of tragic genius – brilliant but ultimately powerless against circumstance – obscures some important truths.

I did accomplish significant work. My Notes represent a genuine intellectual achievement that has survived and been vindicated by history. I was not simply a tragic figure of unrealised potential; I was a person who executed substantial intellectual work.

Furthermore, the tragic narrative can itself become an obstacle to recognising women’s contributions. It allows people to treat women’s work as poignant but ultimately secondary – something to be pitied rather than genuinely engaged with. I would prefer that my work be taken seriously on its intellectual merits, not mourned as the product of a life cut short.

And while my later years were troubled, I do not wish them to overshadow the entirety of my existence. I experienced great intellectual excitement, genuine friendship and collaboration, the satisfaction of engaging with important ideas. I had significant privilege and access. My life had tragedy, but it was not only tragedy.

If you had lived to a greater age, what mathematical or computational problems would you have most wanted to explore?

I was deeply interested in the application of mechanical computation to problems in natural philosophy – to the analysis of dynamical systems, for instance. There are many natural phenomena that evolve according to mathematical rules: the motion of planets under gravitational influence, the vibration of strings or membranes, the propagation of heat through materials.

These phenomena are described by differential equations – mathematical relationships between quantities and their rates of change. Solving these equations by hand is enormously tedious and often impossible through elementary methods. But I perceived that the Analytical Engine, with its capacity to execute iterative procedures, might be able to approximate the solutions to many differential equations.

This would require developing a method to translate the continuous mathematics of differential equations into the discrete, step-by-step operations of the mechanical apparatus. The approximation would not be perfect – there would be errors that accumulated with each step – but it might be sufficiently accurate for practical purposes.

I also was fascinated by the possibility of using the Engine to analyse data. If one had collected a set of observations of some natural phenomenon, could the Engine be instructed to find patterns in that data? Could it be directed to fit mathematical functions to empirical observations, extracting the underlying structure from noise and variation?

These ideas were nascent when my health declined. I did not have the opportunity to develop them into concrete algorithmic forms as I had done with the Bernoulli number algorithm.

These sound like ideas that prefigure concepts that would become central to computing in the twentieth century – numerical analysis, simulation, data analysis.

Yes. Though I did not use such terminology. But I was perceiving that the power of the Analytical Engine lay not merely in performing exact arithmetic calculations, but in its capacity to execute approximative procedures – to follow a rule or algorithm repeatedly, refining results iteratively.

This is fundamental to what would later be called “numerical analysis” – the field that uses discrete, step-by-step mathematical procedures to approximate solutions to problems that cannot be solved through closed-form methods.

And the application to data – finding patterns, fitting models – this anticipates what your era calls “data science” or “machine learning,” though of course the specific methods and the scale of application are vastly different in your time.

Reflections On Collaboration and Isolation

You maintained a substantial correspondence throughout your life with Mary Somerville, your tutor, and with Charles Babbage. These collaborative relationships seem to have been essential to your intellectual development. What was the nature of collaboration for you?

Collaboration, for me, was not a compromise or a necessary accommodation to social barriers. It was an intellectual necessity and a source of genuine pleasure.

With Mrs. Somerville, I had a mentor and a friend. She possessed mathematical knowledge that I lacked, and she had navigated the landscape of scientific work as a woman with greater success than I could imagine. Her example – her publications, her respect within the scientific community – demonstrated that it was possible for a woman to be taken seriously as a practitioner of mathematics and natural philosophy.

But perhaps more importantly, she engaged with my ideas seriously. When I proposed something, she did not dismiss it as the product of youthful enthusiasm or female fancy. She examined it critically and responded thoughtfully. This kind of engagement was rare for me.

With Mr. Babbage, the collaboration was different. He was my intellectual equal in mathematical sophistication, but he came from a position of professional authority and institutional recognition that I could never achieve. When I worked through a problem, I was testing my understanding against his established reputation and knowledge.

But what I valued in him was his willingness to be challenged. If I objected to something he had proposed or suggested an alternative approach, he did not dismiss me on grounds of my sex or my lack of formal credentials. He engaged with the substance of the objection.

Did you have other collaborators or intellectual peers?

Not in the formal sense. There were mathematicians and natural philosophers with whom I corresponded, but my circumstances prevented the kind of ongoing, intensive collaboration that I might have had with peers.

This was a genuine loss. The isolation was difficult. One spends hours thinking through a problem alone, without the benefit of another mind to challenge or extend your thinking. One must rely on written correspondence, which is slower and less immediate than conversation.

I sometimes imagined what it might have been like to be a male mathematician of my ability, studying at Cambridge, attending lectures, meeting with other students and scholars in formal and informal settings, establishing a network of peers with whom one could collaborate throughout one’s career.

The intellectual community that would develop through such channels would be invaluable. I had approximations of this through correspondence, but it was not the same as physical presence and the ongoing engagement that proximity permits.

Do you think your isolation affected the direction of your intellectual work? Would you have developed different ideas had you been less isolated?

Almost certainly. Intellectual development is shaped by community. The questions one pursues are often suggested by the conversations one hears, by the works one discovers through recommendation of peers, by the challenges and objections posed by others engaged in the same domain.

Had I been embedded in an active mathematical community, I might have pursued problems that simply did not come to my attention in my isolated circumstances. I might have developed methods and approaches that were standard in that community but which I had to invent independently.

But there may also be a countervailing advantage to isolation. It forced me to think through problems from first principles, without the constraint of established approaches. I was not socialised into particular ways of thinking about mathematical problems because I was not part of the community in which those ways were transmitted.

My conceptualisation of the Analytical Engine might have been different had I been trained through formal study at a university. I might have learned mechanical philosophy and computing through the categories that were conventional in my time. Because I approached it from outside those conventions, I was able to see the Engine in a way that those embedded in the tradition might not have seen it.

So while isolation imposed costs, it also, paradoxically, may have enabled certain kinds of creative thinking.

Errors, Regrets, and Honest Assessment

I’d like to ask you about mistakes – things you got wrong or would do differently if you could revise your work. In the interest of intellectual honesty, can you identify places where you now believe you made errors?

Yes, there are several things I would revise if I could.

First, in some of my Note A on the Engine’s basic operations, I made some simplifications that, while perhaps necessary for clarity, obscured certain technical difficulties. The Analytical Engine had particular mechanical constraints on how data could flow and how operations could be sequenced. I glossed over some of these constraints in order to present the general principles more clearly. But this left readers without a full appreciation of the practical difficulties involved in implementing computation mechanically.

Second, in my discussion of what the Engine could accomplish, I was perhaps too optimistic about the breadth of applications without having worked through the specific technical details. I speculated about applications to music, to symbolic manipulation more generally, to the analysis of natural phenomena. But I had not actually developed algorithmic methods for these applications. I was gesturing at possibilities rather than demonstrating feasibility.

Third – and this is perhaps more a failure of courage than of intellect – I did not press Mr. Babbage as firmly as I might have about whether the Engine could actually be completed. I knew the project was in difficulty. I knew that his relationship with his engineer had fractured. Yet I did not, in my correspondence, address directly whether the project should be abandoned or whether we should attempt to secure different funding or different technical assistance.

I permitted myself to inhabit the realm of theoretical possibility whilst avoiding the practical reality that the machine might never be built. Had I been more forceful in engaging with that reality, perhaps I might have contributed to solving some of the difficulties that prevented the Engine’s completion.

That’s a fascinating admission. The last point especially – you’re suggesting you had the possibility of changing the course of events but didn’t act on it?

I had some possibility, though I do not wish to overstate my influence. Mr. Babbage was the principal architect and advocate for the Engine. I was a supporter and collaborator, but the institutional and financial obstacles were beyond my capacity to resolve.

But what I might have done was engage more directly with those obstacles. I had connections through my family and my aristocratic position. I might have attempted to facilitate discussions with government officials or other potential funders. I might have encouraged Mr. Babbage to simplify his design to make it more achievable.

Instead, I remained largely in the realm of intellectual engagement with the theory of the Engine whilst allowing the practical difficulties to consume him. This was partly a failure of nerve on my part – I was conscious of my own limitations and of the barriers I faced as a woman attempting to intervene in technical and institutional matters.

Do you regret this?

Yes and no. In one sense, there is little point in extended regret about paths not taken. I was operating within constraints, both institutional and personal. Had I attempted to intervene more forcefully, it is not clear that I would have succeeded. Mr. Babbage’s difficulties with the Engine were fundamentally technical and financial; they may not have been resolvable through any amount of political or social leverage.

But I do regret not trying more forcefully. There is a difference between accepting one’s limitations and simply giving up on the possibility of influence. I perhaps did more of the latter than I would have liked.

The Future of Computing and Human Knowledge

You’ve spent this conversation reflecting on your work of the 1840s and its recognition in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But I want to ask you a forward-looking question. You are now aware of how computers have developed, of the extraordinary advancement in computing power, of the internet, of machine learning and artificial intelligence. What seems most significant to you about this development?

The speed of it. Computation that would have required days of human calculation in my time is now performed in nanoseconds. The machines are incomprehensibly more powerful than anything Babbage imagined.

Yet the fundamental principles remain. Computation is still the manipulation of symbols according to rules. The Analytical Engine’s architecture – with memory, an arithmetic unit, and a control unit directing operations – is recognisable in your contemporary machines. The notion of expressing a method as a sequence of instructions that a machine can execute has become utterly central.

What I did not foresee was the scale. I imagined the Engine calculating Bernoulli numbers, a complex but ultimately circumscribed mathematical task. I did not anticipate that machines would manage the vast portions of human communication, commerce, and knowledge that you tell me they now manage. I did not anticipate that nearly every domain of human endeavour would become mediated by computation.

This raises questions that I find both exciting and troubling. Exciting, because it suggests that the principles I articulated about symbol manipulation and logical structure have proven foundational to understanding human knowledge and information itself. Troubling, because when something becomes so central to human life, the risks of dependence and of embedding errors or biases into those systems become equally magnified.

What concerns you most about how computing has developed?

I am concerned about the same thing I was concerned about in the 1840s, but magnified enormously: the difference between mechanism and intention, between the operations a system performs and the meaning we assign to those operations.

In my time, I insisted that the Analytical Engine has no consciousness, no independent volition. It performs only what we instruct it to perform. I maintained that clarity because I saw a temptation to anthropomorphise the machine, to imagine it as thinking.

In your time, you have machines that process natural language, that generate images, that appear to reason and converse. The temptation to imagine consciousness or understanding in these systems is even greater. And yet, as far as I can gather, these machines remain ultimately symbol-manipulators, operating according to rules derived from data and mathematics.

The danger – the one I perceived dimly and that you now face directly – is that society will begin treating machine outputs as if they contain understanding, judgment, or wisdom, when they are merely the products of statistical operations.

Your era speaks of “artificial intelligence.” I find this term deeply problematic because “intelligence” carries implications of consciousness and understanding that I do not believe machines possess. You have machines capable of performing tasks that previously required human intelligence, but the mechanism by which they accomplish those tasks is fundamentally different from human understanding.

Are you suggesting that society is repeating the errors you warned against – the anthropomorphisation of machines?

I would say that your society faces a more sophisticated version of the problem I identified. It is not naive anthropomorphisation – people in your era generally understand that machines are not conscious. But there is a kind of functional anthropomorphisation, where we treat machines as if they possessed judgment or understanding for practical purposes, even whilst acknowledging theoretically that they do not.

This creates genuine risks. If a machine learning system makes a determination about a person’s creditworthiness or criminality or medical diagnosis, and we treat that determination as if it possessed human-like judgment, we have created a system that can embed biases and errors at scale, without the accountability that human judgment carries.

The solution, as I proposed in my own time, is clarity. We must be clear about what machines are doing: manipulating symbols according to rules. We must be clear about the limitations of those operations. And we must maintain human judgment and responsibility for decisions that affect human lives.

That’s a sobering vision. But I wonder if you’re being too pessimistic. Couldn’t it be argued that your insights about general-purpose symbol manipulation have enabled tremendous benefits – solving medical problems, connecting people across vast distances, enabling scientific discoveries that would have been impossible?

You are correct. I do not wish to dismiss the genuine benefits of computing. The fact that the principles I articulated have led to machines capable of analysing medical data to detect cancers earlier, or enabling scientists to model the behaviour of complex systems, or allowing knowledge to be shared across the world – these are genuine goods.

I am not arguing against the development of computing. I am arguing for clarity, caution, and responsibility in how we deploy these systems. The same symbolic manipulation that enables medical progress can, if not carefully governed, embed discrimination or impose constraints on human freedom.

The question I would pose to your era is: As you develop increasingly powerful computing systems, are you remaining as vigilant as you should be about the distinction between mechanism and meaning, between what a machine can do and what humans should do with that capability?

Closing Reflections

As we approach the end of our conversation, I want to ask you something more personal. You have been celebrated posthumously in ways you never experienced in life. Your work has been vindicated. Your insights have proven prophetic. Yet you died young, in obscurity, with only one published work to your name. If you could speak to your younger self – the young woman struggling with illness, navigating family drama, working intensely on the translation that would become your sole major publication – what would you tell her?