This interview is a dramatised reconstruction based on historical sources, research, and documented accounts of Marlyn Meltzer’s life and work. While her biographical details, technical contributions, and historical context are factual, her words, reflections, and responses to modern questions represent informed historical imagination rather than direct testimony.

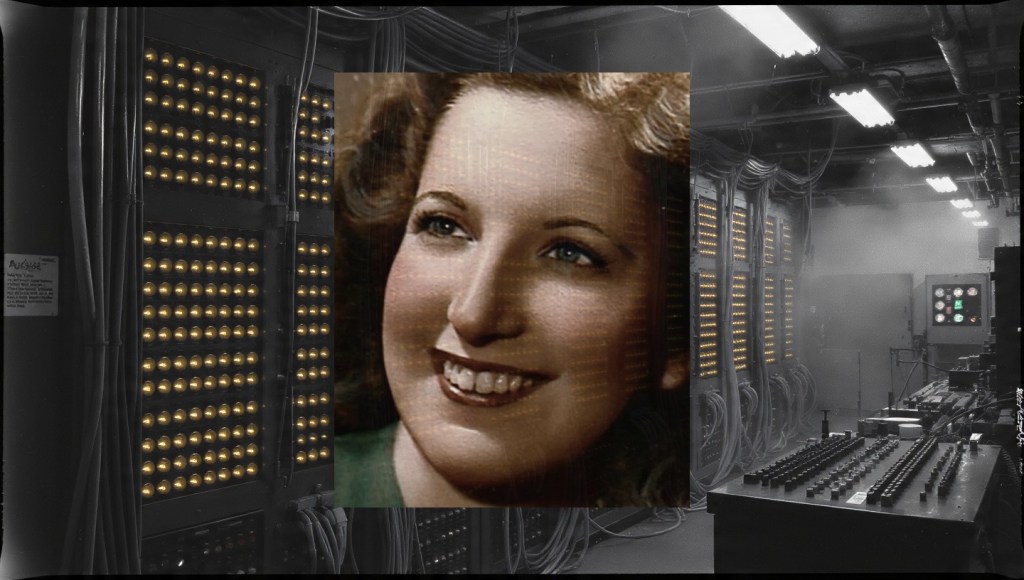

Marlyn Meltzer (1922-2008) was a mathematician who translated the arcane language of differential equations into the physical reality of ENIAC’s 3,000 switches, effectively inventing software engineering before the discipline had a name. Her work on ballistics trajectory calculations demonstrated that electronic computation could reduce forty-hour manual calculations to mere seconds, proving the military value of digital computers at their inception. Though history nearly erased her – the Army credited only male engineers at ENIAC’s 1946 debut, and marriage forced her from the field just as computing professionalised – her legacy endures in every program executed today, and in the more than 500 chemotherapy hats she knitted for cancer patients in her later years.

Marlyn, thank you for joining me. I realise how peculiar this must feel – speaking across the decades – but I hope you know we’ve been working our way through your colleagues. Jean Bartik told us about the debugging breakthroughs, Kathleen Antonelli described the sheer physicality of the machine, Betty Holberton shared her insights on the master programmer, Ruth Teitelbaum explained the numerical integration methods, and Frances Spence reflected on the collaborative spirit you all shared. You’re the final voice in this series, and perhaps the most elusive. When I mention your name to modern computer scientists, I often see recognition flicker, then fade. They know they should know you, but the details have slipped through history’s fingers. How does that feel, looking back?

Elusive. That’s a kind word for it. We were taught to be invisible, you understand. When they wheeled ENIAC out for the press in February 1946 – those enormous cameras, the reporters shouting questions – they told us five girls to stand near the machine and look pretty. “Refrigerator ladies,” some called us later, as if we were showroom models. The Army handed out press packets with Hermann’s name, Eckert’s, Mauchly’s. Not ours. So “elusive” seems about right. We learned to vanish before we learned we mattered.

Let’s fix that, shall we? I’d like to start where your journey began – not with ENIAC, but with the adding machine. You were hired initially for your ability to operate a Marchant calculator. What did that work actually involve?

People think “calculator” and picture something small. The Marchant weighed thirty-five pounds. You didn’t just press buttons – you orchestrated them. Each multiplication required a specific rhythm: clear the register, enter the multiplicand, set the multiplier digits, crank the handle for each place value, watch the carriage shift with a heavy clunk. We computed weather patterns at first, then ballistics tables. A single trajectory might take forty hours by hand. Forty hours of cranking, checking, re-cranking when you found an error. My fingers developed calluses in specific places. You could identify a “computer” – that’s what they called us, “computers,” the job title – by the sound of her calculator carriage and the state of her hands.

The transition from those mechanical calculators to ENIAC must have felt like stepping from a horse-drawn carriage into a spacecraft. You’ve described teaching yourselves programming from schematic diagrams without manuals. Please can you explain it to me as you would to a fellow mathematician who understands numerical methods but has never seen a digital computer?

Imagine you’ve spent your entire career solving differential equations for artillery trajectories using the Bush differential analyser – a magnificent analogue device, all wheels and gears. You understand the mathematics: the equations of motion, drag coefficients, air density variations with altitude, Coriolis effects. You know how to set up the integration routines manually. Now someone shows you a room filled with forty panels, each eight feet tall, covered with switches – 3,000 of them – and between the panels, thick cables like telephone cords, patch cords we called them. No instruction manual. Just wiring diagrams.

Here’s what we did. Betty Snyder – Betty Holberton, she became – she noticed first that the switches represented states. On or off. One or zero. The patch cords routed pulses. We realised ENIAC was essentially a massive electronic switchboard, like the telephone exchanges we understood. Each panel performed a function: accumulators for addition, multipliers, function tables for storing constants, a master programmer for sequencing.

The breakthrough was understanding that we could store the program in the machine’s state. With the differential analyser, you physically reconfigured the machine for each problem. With ENIAC, you set the switches and cables to represent both the data and the operations. You were wiring the algorithm itself into the hardware. We started with simple test problems: can we make it count? Can we make it multiply? Then we translated the ballistics equations.

The numerical integration was the core. For a trajectory, you integrate acceleration to get velocity, velocity to get position. We broke this into discrete time steps – say, one-thousandth of a second. At each step, you calculate the drag force based on current velocity, update acceleration, then velocity, then position. We programmed ENIAC to perform this loop automatically. The function tables stored the drag coefficients for different velocities and altitudes – values we had to punch into the machine by hand, thousands of them. The accumulators held the running totals. The master programmer counted the iterations.

The genius – if I can call it that – was realising we could use the same hardware configuration to solve any problem that could be expressed as a sequence of arithmetic operations. We were abstracting mathematics into electronic states. That’s what programming is, though we didn’t have the word yet.

You mention the function tables. I’ve read that punching those values – thousands of drag coefficients – was itself a monumental task. What did that physical process look like?

Each function table was a panel with switches arranged in a grid. You set them in binary – up for one, down for zero. For a single drag coefficient, you might need ten switches. For a complete trajectory table, you needed coefficients for velocities from zero to three thousand feet per second, in increments of maybe ten feet per second, and for altitudes from sea level to forty thousand feet. That’s thousands of values. Each one had to be calculated separately – by hand, using reference data – and then converted to binary and set by hand.

We worked in pairs, reading values aloud while the other set switches. “Panel three, row twelve, coefficient for Mach point six at ten thousand feet: zero-one-zero-one-one-zero-one-one-zero-zero.” Click, click, click. The sound of three thousand switches being set is memorable. A soft, precise snapping. Like knitting, in a way – repetitive, requiring concentration, each action small but essential to the whole. If you got one switch wrong, the entire trajectory would be wrong. We developed checking procedures: set a row, verify it, have your partner verify it. Betty created a system of checksums – adding up rows of values and comparing them to expected totals. We were debugging before we knew the term.

The press release at ENIAC’s debut described the male engineers as having created a “Giant Brain” that could compute in seconds what took humans days. But you and your colleagues had already proved its military value through the trajectory calculations. What was your reaction when you saw how the Army framed that moment?

We were in the room, you understand. Behind the ropes, where they told us to stand. I remember watching Hermann Goldstine – lovely man, brilliant – demonstrating the machine. He pressed a button, and ENIAC calculated a trajectory in seconds. The reporters gasped. Cameras flashed. They wrote about the “electronic super-brain.” And we stood there, the five of us who remained – Ruth and Frances had already moved to Aberdeen – wearing our best dresses, instructed not to speak unless spoken to directly.

The irony was this: that demonstration trajectory? We’d programmed it. We’d punched the function tables. We’d debugged the integration loops. We knew exactly which patch cords routed which data, which accumulator held the velocity vector, which panel calculated the Coriolis correction. But the press release credited “the engineers at the Moore School.” Not “the mathematicians and programmers.” Never that.

I don’t think it was malice. It was blindness. They saw the machine – this magnificent, thirty-ton creation of tubes and wires – and they saw the men who designed it. They didn’t see the work of translating mathematics into electronic operations because that work was invisible by design. It happened inside our heads, then disappeared into the switch settings. No physical artifact remained. The machine was the artifact. So they thought the machine was the point.

You left ENIAC in 1947 to marry. I’ve always wondered about that moment. Was it a choice you made freely, or did you feel the era’s expectations closing in around you?

It’s complicated, isn’t it? I married Abe Meltzer in June 1947. He was a lovely man, a dentist. And yes, the expectation was there – married women didn’t work in technical positions, especially not in classified military projects. The Moore School had an unwritten rule. Most companies did. The men who ran things assumed you’d get pregnant, that your loyalties would shift, that you couldn’t be trusted with secret work.

But here’s what history doesn’t record: I was tired. Programming ENIAC was exhilarating, but it was also exhausting. The machine broke down constantly – tubes failing, connections loosening. We worked six-day weeks, sometimes seven. And I looked at the path ahead: ENIAC was moving to Aberdeen, the culture was shifting toward male engineers taking over programming, and I’d be fighting not just the machine but institutional bias that grew stronger each day.

When Abe proposed, part of me thought, “Here’s a different life. A stable life.” And I took it. Not because I lacked ambition, but because the alternative seemed like swimming upstream forever. Was it a mistake? In some ways, yes. I left just as the field I helped create was becoming a profession. But I also gained a good marriage, two daughters, a community. You can’t live a life wishing you’d chosen differently. You choose, and you make that choice worthwhile.

Did you ever regret leaving computing? Did you follow the field’s development?

Of course I followed it. How could I not? When Fortran appeared in the mid-fifties, I read about it with fascination. High-level languages – what a concept! We programmed in machine configuration, and now people were writing code that looked almost like algebra. When integrated circuits arrived, I thought about those 17,468 vacuum tubes in ENIAC, each one burning out every few days. The reliability we dreamed of.

Did I regret leaving? Some days, yes. When I read about the Apollo guidance computer, I thought: we laid the groundwork for that. When I saw my daughters struggling with punch cards in their university computing courses in the seventies, I smiled – punch cards we never used, but the sequential logic was ours. When I heard about women being pushed out of tech in the eighties and nineties, I felt a familiar ache. The same patterns, repeating.

But regret is a luxury. I chose a different path. And honestly, the way the field professionalised – men with engineering degrees pushing out the mathematicians, the increasingly competitive culture – it might not have been a place I fit anyway. We were collaborators, the six of us. We shared everything. That spirit seemed to vanish as computing grew up.

Let’s talk about that collaboration. You’ve mentioned the six of you working together. What was the division of labour like? What was your particular specialty?

We each had our strengths. Betty Snyder – Holberton – she was the systems thinker. She saw the whole problem at once, could map an entire calculation onto ENIAC’s architecture. Kay McNulty – Kathleen Antonelli – had the deepest mathematical intuition. She could spot an error in the numerical methods before anyone else. Jean Bartik was our debugger supreme; she had patience for tracing signals through the panels that the rest of us lacked. Ruth Teitelbaum and Frances Spence were precise, meticulous – they never made setting errors.

My specialty was the ballistics mathematics itself. I’d worked on those trajectory calculations for months before ENIAC. I understood the differential equations intimately – the way drag coefficients varied with Mach number, the atmospheric density tables, the Coriolis corrections for Earth’s rotation. When we translated the problem to ENIAC, I could say: “Here, this accumulator needs to hold the current altitude, this one the velocity magnitude, this function table must store the drag values for supersonic speeds.” I was the bridge between the mathematical problem and the machine configuration.

But here’s what we did that nobody talks about: we created standards. Betty developed a notation system – she’d sketch the switch settings and patch cord routes on paper, a visual program. Kay created verification methods – running known test cases through partial configurations. I developed what you’d now call a “test harness” – a simple loop that would run a single iteration of the integration so we could inspect intermediate values. We were building methodology as we went.

You’ve mentioned errors and debugging. I’d like to hear about a specific failure – a time when something went profoundly wrong, and what you learned from it.

Oh, the Great Trajectory Disaster of February 1946. We’d been running test calculations for weeks, getting beautiful results. The trajectories matched the hand-calculated tables within 0.1% – well within tolerance. Then one morning, we ran a standard test case: a 105mm howitzer shell, forty-five-degree elevation, standard atmospheric conditions. ENIAC calculated a range of 8,765 metres. The official table said 8,452 metres. A three-percent error – catastrophic in artillery.

We spent three days debugging. Checked the function tables – correct. Verified the integration loop – correct. Examined the patch cords – correct. The error was consistent: every trajectory came out slightly long. Finally, Jean noticed something odd in the accumulator readouts. The velocity values were drifting upward in a way that suggested a rounding error. But ENIAC didn’t round – it truncated.

Here’s what we’d missed: in our manual calculations, we used rounding. At each integration step, if the value was 123.6, we recorded 124. ENIAC, being digital, dropped the fractional part – 123.6 became 123. Over thousands of iterations, this truncation bias accumulated. The machine was mathematically precise but numerically naive. We were asking it to perform a calculation method developed for human computers who naturally rounded.

The solution was elegant: we added a constant 0.5 to each value before truncation, forcing proper rounding. But the lesson was deeper: algorithms designed for humans don’t always translate directly to machines. You must understand both the mathematics and the machine’s nature. That’s a principle that still applies, I imagine.

It absolutely does. Modern machine learning faces similar issues with numerical precision. Your team essentially discovered what we’d now call “algorithmic bias” – not social bias, but mathematical bias introduced by implementation details.

Algorithmic bias. I like that. We just called it “the machine being too literal.” But yes, the machine does exactly what you tell it, not what you intend. That’s both its power and its peril. We learned to be extremely precise in our intentions.

You left the field in 1947, but your colleagues who stayed – Jean Bartik, Betty Holberton – they later faced explicit discrimination. Jean was told “we don’t hire women programmers” in the 1960s. Betty had to fight for credit. When you hear about that, what goes through your mind?

Anger, mostly. And a kind of exhausted recognition. We assumed we were opening doors. We thought proving that women could do this work – mastering the most complex machine in existence – would change things. But what we did was more fragile than we realised. We created proof, but proof doesn’t matter if people don’t want to see it.

The tragedy is this: we were good at the work. Not just competent – exceptional. We taught ourselves to program without manuals, created methodologies from scratch, solved problems the male engineers couldn’t because they didn’t understand the mathematics deeply enough. And for what? So that a decade later, they could claim “women aren’t suited for programming”? It’s farcical.

But here’s what I want you to understand: we were the pipeline. We weren’t exceptions. We were the rule. Women did this work because it was new, because there were no men with experience, because we were available and capable. The pipeline didn’t fail. It was deliberately dismantled.

Your later life – volunteering at the library, delivering Meals on Wheels for over a decade, knitting more than five hundred chemotherapy hats for cancer patients – seems like a completely different world from ENIAC’s panels and vacuum tubes. Was there a continuity you felt between that mathematical precision and that community service?

People see those as separate lives, but they weren’t. Precision matters whether you’re setting three thousand switches or following a chemotherapy hat pattern that must fit just so on a bald head scarred by radiation. Organisation matters whether you’re routing data through ENIAC’s accumulators or scheduling Meals on Wheels routes so that hot food reaches seventeen elderly people before it cools.

When I delivered meals, I used a system. Mapped the routes by travel time, accounting for traffic patterns, grouping addresses by proximity. I’d created an optimisation problem and solved it. The other volunteers teased me about my “military precision,” but we delivered more meals, more efficiently, because of it.

The hats – each one took four hours to knit. I kept a log: pattern variations, yarn types, sizes. I experimented with edge treatments that wouldn’t irritate sensitive skin. That’s research and development, just with different materials. The five hundred hats weren’t a random act; they were a production run, quality-controlled and purpose-driven.

Computation taught me that small, repeated actions, perfectly executed, create enormous outcomes. So did volunteer work. The scale differs, but the principle is the same.

That’s a profound connection. You mention keeping logs and optimising routes – computational thinking applied to care work. Do you see that pattern in how women today apply technical skills to community problems?

I see it constantly, though they may not call it that. The women organising mutual aid networks during the pandemic – they were building distributed systems, creating redundancy, managing resource allocation. Those running community food programmes are doing logistics optimisation. The ones fighting for better school funding are performing cost-benefit analyses with incomplete data, just as we did with ENIAC’s uncertain tube lifespans.

The difference is recognition. When we programmed ENIAC, our work was invisible because it was secret and because we were women. When women today apply computational thinking to community care, it’s invisible because it’s unpaid and because it’s “women’s work.” The pattern persists: technical brilliance in service of community is erased, while technical brilliance in service of profit is celebrated.

You’ve been remarkably candid about the challenges. What would you say to a young woman starting in computing today, perhaps facing different but parallel barriers?

I’d say this: document everything. Keep records. Write down what you do, how you solve problems, what you discover. We didn’t, enough. We were too busy doing the work, and we assumed our contributions would be obvious. They weren’t. They were buried.

Second, find your colleagues. We six supported each other in ways that made the work possible. When Betty got stuck on a routing problem, Kay would spot the solution. When I was ready to throw something at the machine – yes, I came close – Jean would make me step back and trace the signal flow calmly. You need people who understand both the technical challenge and the institutional landscape.

Third, accept that being first means being doubted. When we proved ENIAC could calculate trajectories faster than any human, the engineers doubted our results. They re-ran our calculations by hand. It took them weeks to verify what ENIAC did in seconds. Be prepared for that. Your proof will be scrutinised more heavily because you don’t fit the expected pattern.

And finally – this is the hard one – know when to leave. I left because the barriers seemed insurmountable and another life called to me. That was right for me. But if you stay, stay because you want to, not because you feel you must prove something. The burden of representation is heavy enough without adding martyrdom.

That’s both practical and profound. I want to ask about something specific. You’ve mentioned the physicality of ENIAC – the weight of the panels, the texture of the patch cords, the sound of switches. Can you describe the sensory experience of programming that machine? What did it feel like in your body?

The Moore School’s basement had a particular smell: ozone from the vacuum tubes, warm dust from the cooling fans, machine oil from the function table mechanisms. When ENIAC ran a full calculation, the heat was incredible. One hundred fifty kilowatts of electricity converts to warmth quite efficiently. We’d work in summer dresses even in winter, and still sweat.

The patch cords were thick, rubberised, like heavy telephone cables. Your hands would tire plugging and unplugging them. We developed a technique: palm the connector, align by feel, push with the heel of your hand until you heard the click. After a full day, your shoulders ached from reaching into the panels, your fingertips were numb from snapping switches.

The sound… ENIAC had a rhythm. Accumulators pulsed at 100 kilohertz – a high-pitched whine you felt in your teeth. When it completed a calculation, there was a moment of silence, then the clatter of printer output. We learned to diagnose problems by sound. If the pitch changed, a tube was failing. If the rhythm stuttered, a patch cord was loose. We listened to the machine like a doctor listens to a heartbeat.

It was fully embodied work. You didn’t send your program to a computer; you became part of the computer while you programmed it. Your body learned the patterns. I could close my eyes and trace a signal path through the panels in my mind because my hands had traced it physically a hundred times.

You mentioned the printer output. I’ve seen photographs of those printouts – long strips of paper with columns of numbers. What did you do with those results? How did you verify such massive outputs?

Verification was our constant companion. The printer spewed numbers at ferocious speed – ten lines per second. For a full trajectory, that might be five hundred lines: time, position coordinates, velocity components, at each integration step. We couldn’t possibly check every value against hand calculations. That would defeat the purpose.

So we sampled. We’d verify the first ten steps manually, the last ten, and random points in between. We checked boundary conditions: at time zero, position and velocity must match the initial conditions. At impact, the altitude must be zero. We looked for physical plausibility: velocity shouldn’t exceed realistic limits, the trajectory should be smooth.

Betty created what she called “conservation checks.” Total energy should remain constant minus drag losses. Momentum should follow predictable patterns. If those invariants held, the detailed numbers were likely correct. It was statistical validation – spot-checking with purpose.

We also ran known test cases: trajectories we’d calculated exhaustively by hand. If ENIAC matched those within tolerance – usually 0.1% relative error – we trusted it for new cases. That first time it worked, when we saw ENIAC produce a correct trajectory in seconds that had taken us forty hours manually… I don’t have words for that feeling. Validation, pride, a touch of terror at what we’d unleashed.

The terror of making oneself obsolete?

The terror of speed. We realised that night – February 1946, after the press had gone and we were alone with the machine – that we’d crossed a threshold. Computation was no longer limited by human speed. It was limited by human imagination. And we weren’t sure humanity was ready for that.

Yet you left that world shortly after. When you look at computing today – microscopic transistors, billions of calculations per second, software that writes software – what connects most strongly to your experience?

The debugging. The sheer, maddening, essential work of finding out why something that should work doesn’t. I read about modern programmers hunting memory leaks or race conditions, and I think: yes. That’s exactly what we did, just with slower clocks and more obvious hardware. The intellectual process is identical: form a hypothesis, test it, refine it, test again.

Also, the gap between intention and implementation. We intended to calculate trajectories accurately; ENIAC did what we told it, which initially wasn’t quite the same thing. Today, you intend a neural network to recognise faces; it does what you told it, which may include biases you didn’t consciously encode. The problem scales, but its nature persists.

What I don’t recognise is the isolation. We worked shoulder to shoulder, literally. You couldn’t program ENIAC alone – it was too complex, too physical. Modern programmers sit in separate cubicles, communicating through screens. That seems lonely.

It often is. Your generation created fundamental practices – sequencing, debugging, optimisation – that underpin modern computing. Yet you were classified as “computers,” a subprofessional role. How did you understand your own expertise at the time? Did you feel like engineers? Mathematicians? Something new?

We felt like pioneers without a map. The term “programmer” didn’t exist, so we used what we had: “computer,” the job title for human calculators. But we knew the work was different. Setting up ENIAC wasn’t calculating; it was configuring. We were translating mathematical logic into machine logic. That’s what engineers do, yes? But we weren’t trained as engineers. We were mathematicians who’d learned electronics by necessity.

Betty once said we were “machine linguists,” which I rather liked. We were learning to speak ENIAC’s language, which was entirely physical. Later, when “programmer” emerged as a term, it felt right. But by then, I’d left.

The classification as “subprofessional” stung, of course. We earned $2,000 a year. The male engineers earned $4,000-$5,000. They had degrees in electrical engineering; we had degrees in mathematics. Their work was visible – schematics, hardware. Ours was ephemeral – configurations that vanished when the machine powered down. We couldn’t point to our work and say “I built that” because the building was conceptual. So they called it operating, not engineering.

You’ve described your departure as partly your choice, partly the era’s expectations. What would it have taken for you to stay? What would a viable path have looked like?

A title, for one. “Programmer” with a professional salary. Recognition in official project documentation. The Army could have offered that. They didn’t.

Childcare. The other women who stayed – Jean, Betty – they either delayed families or had husbands willing to share domestic work. In 1947, that was rare. If the Moore School had said, “Your work is essential; we’ll support you through a pregnancy, provide childcare, keep your clearance,” that might have changed my calculus.

But the deepest issue was cultural. The project was becoming less mathematical, more engineering-focused. The men coming in – brilliant men, don’t misunderstand – saw programming as a support function, not core research. They’d design hardware, we’d operate it. That division would have chafed. I was a mathematician first. I wanted to solve problems, not implement others’ solutions.

So I’d have needed a role where I could grow mathematically, where programming was recognised as problem-solving, not just implementation. That role didn’t exist in 1947. It barely exists now, though it’s better.

You’ve been candid about the institutional barriers, but I wonder if you could be equally candid about your own limitations. What was genuinely hard for you, personally, in that work?

The social navigation. I’m a mathematician at heart – I see patterns, structures, logical flows. People are less predictable. The politics at the Moore School, the subtle competitions between engineers, the way credit was allocated through social networks rather than pure contribution… I found that exhausting.

I also struggled with the impossibility of perfection. With manual calculation, you could verify every step. With ENIAC, you had to trust. Trust the machine, trust your programming, trust the sampling verification. I lost sleep worrying about undetected errors. What if a tube failed mid-calculation and introduced a subtle error we didn’t catch? What if our rounding fix wasn’t sufficient for supersonic trajectories? The responsibility was immense – soldiers’ lives depended on those firing tables being accurate. I carried that weight heavily.

And I’ll admit: I was slower than some. Betty and Kay could configure panels in their heads, visualising the entire setup before touching a switch. I needed to work methodically, checking each step. My strength was thoroughness, not speed. In a culture that valued rapid progress, I sometimes felt like the cautious one holding everyone back.

That thoroughness – your attention to the ballistics mathematics, the physical plausibility checks, the conservation laws – sounds like it was essential to ENIAC’s success. It wasn’t a limitation; it was a complementary skill.

Perhaps. But when you’re twenty-four and surrounded by brilliant people who seem to work twice as fast, you don’t see complementarity. You see inadequacy. It took me years to understand that my meticulousness had value. By then, I’d left the field.

You mentioned earlier that you see modern computing’s problems as scaled versions of ENIAC’s challenges. Let’s explore that. Modern AI systems sometimes produce “hallucinations” – confident but incorrect outputs. You faced a version of this with your Great Trajectory Disaster. What advice would you give today’s engineers?

Validate invariants. ENIAC’s error was subtle because energy wasn’t conserved correctly due to truncation bias. We should have checked that invariant from the start. Modern AI systems need similar invariant checks: does this answer preserve logical consistency? Does it violate known physical laws? Does it contradict its training data in ways that suggest hallucination?

Also, interpretability matters. With ENIAC, we could trace every signal. Modern systems are black boxes. That’s dangerous. You need mechanisms to inspect intermediate states, to understand why a system produced an output. We called it “single-stepping” – running one integration cycle and examining all registers. AI needs equivalent tools.

And finally, diversity of perspective. The six of us caught errors that any one of us would have missed because we thought differently. Betty saw systems, Kay saw mathematics, Jean saw signals, Ruth and Frances saw details, I saw physical plausibility. Homogeneous teams have homogeneous blind spots. That was true in 1946; it’s true now.

Your life after computing – volunteer work, community service, knitting those hats – has been described as a pivot away from technology. But you’ve reframed it as applying computational thinking to care work. Do you think history has undervalued that part of your life compared to your ENIAC work?

Yes, but I understand why. ENIAC was historically significant; Meals on Wheels was locally significant. The scale differs. But the through-line is me: the same mind that traced signal flow through forty panels traced the most efficient route to deliver seventeen meals. The same fingers that set three thousand switches knitted five hundred hats. The work changes, but the worker doesn’t.

I think the undervaluing reflects a deeper bias: we prize innovation over maintenance, creation over care. ENIAC was creation; chemotherapy hats are maintenance. But both require skill, dedication, precision. A hat that chafes a radiation-burned scalp is as much a failure as a trajectory calculation with three percent error. The consequences differ in scale, but the principle of doing work that matters to someone is identical.

What I regret isn’t the volunteer work being undervalued – it’s that people see it as separate from my technical self. It wasn’t. It was the same person, applying the same mindset to different problems. The tragedy isn’t that history forgets the hats; it’s that it doesn’t see them as continuous with the computing.

You passed away in 2008, before many of the recent recognitions – the expanded documentaries, the renewed historical interest. How does it feel to speak now, knowing your story is finally being told?

Strange. I lived a full life without public recognition. I had a good marriage, raised daughters, served my community, died surrounded by family. That was enough. The belated fame is… disorienting.

But I’m glad for the others still living – Jean, Kay – who got to see it. I’m glad for Kathy Kleiman, who fought to preserve our stories. I’m glad for the young women who email my daughters saying Marlyn Meltzer inspired them to study computer science. That’s a legacy I didn’t expect.

What I hope, more than recognition, is understanding. Not just that six women programmed ENIAC, but how we did it: the creativity, the rigour, the collaboration. The physical labour of it. The intellectual invention. The way we bridged analogue and digital, mathematics and machinery. And I hope they understand why we vanished – not because we failed, but because the world wasn’t ready for us to succeed.

Marlyn, you’ve given us something precious today: not just the facts of your work, but the texture of it – the weight of patch cords, the sound of switches, the anxiety of verification, the pride of invention. Your colleagues each brought distinct perspectives; yours feels particularly grounded in the physical reality of the machine and the mathematical reality of the problems it solved.

The ground is where I stood. Betty dreamed in systems, Kay in equations. I stood with the machine, feeling its heat, hearing its pulse, translating between the abstract and the concrete. Someone had to be the bridge.

And what a bridge you built. The millions of programs running at this moment – all descend from the methods you and your colleagues invented. The world finally knows your name, Marlyn. I hope that matters.

Names matter. But the work mattered more. We didn’t do it for recognition; we did it because the problem was beautiful and the solution seemed possible. That impulse – to solve what’s solvable, to make what’s useful – that’s what I hope survives. Whether your name is in the history books or on a volunteer roster, what counts is the precision of your effort and the care you bring to it. Everything else is just switches waiting to be set.

Letters and emails

Since publishing this interview, we’ve received dozens of letters and emails from readers across the globe – mathematicians, engineers, historians, students, and those simply moved by Marlyn’s story. They’ve asked us thoughtful questions about her technical innovations, her choices, her perspective on modern computing, and what wisdom she might offer to those following similar paths in STEM. Below, we’ve selected five of these contributions, each from a different corner of the world, each offering a distinct angle on Marlyn’s life and legacy. These questions capture what many of you have been wondering: how her pioneering work speaks to challenges we face today, what she would make of our current technological landscape, and how her journey – marked by brilliance, erasure, and quiet service – might illuminate our own.

Élodie Gagnon, 32, aerospace engineer, Montreal, Canada:

Marlyn, looking back at your experience with configuring ENIAC’s switches to solve differential equations, do you see the principles you used then reflected in today’s programming for mission-critical systems, such as aerospace trajectory software? Are there lessons you’d want current engineers to remember?

Élodie, that’s a thoughtful question. Let me think on it.

The principles? They haven’t changed a bit, though the machinery has shrunk considerably. When we programmed ENIAC for ballistics trajectories, we lived by three rules that I reckon still hold for your aerospace work today.

First: know your invariants. We checked energy conservation on every trajectory because if that drifted, the whole calculation was rubbish. For a Mars rover landing, I imagine you check momentum, energy, and positional constraints just the same. The difference is we could trace every electron through the vacuum tubes. You can’t. But the principle – validate what must be true, not just what seems true – that’s timeless.

Second: the machine is literal. ENIAC did exactly what we told it, not what we meant. That three percent error in our early trajectories? We meant to round numbers; we told ENIAC to truncate. The gap between intention and implementation nearly sank the whole demonstration. Your modern compilers and high-level languages hide that gap, but it’s still there. I’ve read about your “software bugs” causing launch failures. Same problem, fancier packaging. My advice: never trust the abstraction. Always know what the hardware is actually doing.

Third: physical understanding matters. I could program ENIAC well because I’d spent months calculating trajectories by hand on Marchant calculators. I knew the drag curves by heart, understood how Coriolis twisted the path, could picture the shell’s arc in my mind. When Betty Snyder mapped the equations to panels, I’d catch physical impossibilities – velocities too high, altitudes wrong – before we even ran the program. Pure mathematicians missed those.

You modern engineers have simulation tools we couldn’t dream of. But I wonder: do you still do the hand calculations? Do you sketch the trajectory on graph paper first? The danger of powerful tools is losing touch with the reality underneath. When our trajectory error appeared, I knew it was wrong because the numbers felt off. My fingers had cranked too many similar calculations. That physical intuition saved us.

The lesson? Don’t let the computer think for you. Let it calculate, but you must understand. We had no choice – ENIAC was too crude to trust blindly. You have a choice, and choosing to stay connected to the fundamentals is harder now. But just as necessary.

One more thing, and this is important: collaborative verification. No one person verified ENIAC’s output. Betty would check the logic, Kay the mathematics, Jean the signal flow, Ruth and Frances the switch settings. Then I’d run physical plausibility checks. We caught errors because we looked from five different angles. I read that today you have “code reviews.” Good. But make them real reviews, not rubber stamps. Make people defend their algorithms out loud, show their work, explain why the invariants hold. That’s how we kept ENIAC honest.

The scale has changed, but the core problem hasn’t: complex systems fail in ways simple ones don’t. We learned to respect that truth. You must too.

Pedro Alves, 35, historian of science, Lisbon, Portugal:

Marlyn, considering the ethical landscape that has evolved around automation and artificial intelligence, what parallels do you see between the pressures your team encountered – for speed and accuracy in military tech – and the dilemmas programmers face now when algorithms may shape critical decisions in society?

Pedro, that’s a sharp question. The parallels are stronger than you might think, though the scale has changed.

When we programmed ENIAC for ballistics tables, the pressure wasn’t abstract – it was immediate and lethal. Soldiers in the field were using firing tables that were outdated or incomplete. If our calculations were wrong, men died. Simple as that. The Army made that clear from day one: speed matters, but accuracy matters more. A shell that falls short hits your own lines.

Here’s what we did to manage that pressure. First, we built verification into every step. Betty Snyder – she became Holberton – insisted on “dual-path validation.” We’d calculate the same trajectory two different ways on ENIAC: once with standard integration, once with a simplified method. If the results didn’t match within tolerance, we didn’t trust either. The Army thought we were being slow. We were being responsible.

Second, we never let the machine’s speed dazzle us into trust. Eckert and Mauchly would show off ENIAC’s raw power – thousands of calculations per second – and the brass would get glassy-eyed with possibility. We’d have to pull them back: “Yes, sir, it’s fast. But we need three days to verify the function tables are punched correctly. The machine can’t check its own inputs.” That was our ethical line: speed is a tool, not a virtue.

Third, we worked in plain sight of each other. No single person controlled the process. Ruth Teitelbaum would set the switches, Frances Spence would verify them, Kay McNulty would check the mathematics, Jean Bartik would trace the signal flow, and I’d run the physical plausibility tests. We caught each other’s errors because we had to. The responsibility was distributed, not concentrated.

Now, from what I’ve read about your modern AI systems, the parallels are there, but the safeguards seem thinner. You’ve got algorithms making loan decisions, diagnosing illnesses, even guiding vehicles. The stakes are just as high as artillery, but I wonder – do you have dual-path validation built in? Or do you trust the machine because it’s fast and sounds confident?

The thing that worries me is the black box problem. With ENIAC, we could trace every electron. Literally. If the output was wrong, we could find the failed tube, the loose patch cord, the mis-set switch. Today, you say your neural networks have millions of parameters no one can interpret. That’s not a feature – that’s a failure of engineering ethics. If you can’t explain why the machine made a decision, you shouldn’t let it make decisions that matter.

I see the same pressure we faced: “Get it working fast, demonstrate the capability, worry about the edge cases later.” That thinking works fine for a chess program. It kills people when you’re deciding who gets a mortgage or which tumour is malignant.

The difference is cultural memory. We had World War II fresh in our minds. We’d seen technology fail catastrophically – bombs that fell on the wrong coordinates, encryption that was cracked. We were humble because we’d witnessed hubris. Your generation grew up with computers that mostly work, so you trust them perhaps more than you should.

My advice? Slow down. Build verification into the design, not as an afterthought. Make algorithms explainable – even if that means simpler systems. And never, ever let one person or one machine hold sole responsibility for a decision that affects human lives. We learned that in 1946. You shouldn’t have to learn it again the hard way.

The volunteer work I did later – Meals on Wheels, those chemotherapy hats – taught me something too. In care work, you can’t outsource responsibility. If a meal doesn’t arrive, a person goes hungry. If a hat chafes, a patient suffers. The ethic is direct and personal. Computing needs that same directness. The machine is fast, but you remain responsible. Never forget that.

Althea Cruz, 27, data scientist, Quezon City, Philippines:

Your early work involved integrating huge sets of weather and ballistics data by hand before automation was possible. If given access to the big data tools and machine learning of today, how do you imagine you and your team would have approached those massive computations differently – especially regarding error checking and validation?

Althea, you’ve hit on something profound. That very thought has stayed with me for a long time.

Hand calculation wasn’t just our method – it was our education. When I cranked those Marchant calculators for weather patterns, each number dug itself into my memory. I knew the reasonable range for barometric pressure at altitude, could spot a corrupted data point because it felt wrong. My fingers learned the curves of normal distributions before my mind could articulate them. That physical intimacy with data – it’s irreplaceable.

If you handed me today’s tools? I’d be dazzled, terrified, then methodical.

First, we’d use your big data systems for exploration, not conclusion. We had to guess which variables mattered – temperature, pressure, humidity, wind shear – and we were often wrong. Your tools could show us correlations we never imagined. But here’s the key: we’d never trust the machine’s pattern without understanding the physics underneath. If your algorithm says “altitude and drag correlate in this odd way,” we’d pull out the fluid dynamics equations and verify why. The data might reveal; mathematics explains.

Error checking? We’d bring our old methods forward. Betty Snyder – Holberton, she became – she created checksums for our function tables. We’d do the same: make your systems calculate each trajectory two ways. One with your neural networks, one with classical numerical integration. If they disagree beyond tolerance, both are suspect. You call it “ensemble methods.” We called it “not being stupid.”

The validation would be stricter, not looser. With hand calculations, errors were limited by human speed. Your machine can make millions of mistakes per second. We’d implement what I call “physical plausibility gates” – hard limits the data can’t cross. A calculated wind speed of 500 knots at sea level? Impossible. The system should reject its own output.

Kay McNulty had a brilliant trick: she’d run a simplified version of the full problem first, something she could verify mentally. If that failed, the full setup was certainly wrong. We’d make your machine learning do the same: build a tiny, interpretable model first. Validate the small before trusting the large.

But here’s what worries me about your “big data” – it learns from past data, which contains past biases. Our ballistics tables had bias too. They assumed standard atmospheric conditions, which rarely exist in combat. We knew that and added correction factors. Does your AI know its own blind spots? Or does it confidently repeat historical errors?

The knitting I did later – those chemotherapy hats – taught me something about automation. I could have bought hats. But hand-knitting let me feel the yarn, adjust tension, notice when a pattern chafed. That feedback loop – hands, mind, material – caught problems early. Your machine learning needs equivalent feedback: humans checking outputs with domain knowledge, not just statistical metrics.

We’d use your tools, yes. But we’d keep our hands in the work, our minds on the mathematics, and our scepticism fully engaged. Speed is seductive. Accuracy is hard-won. Don’t let the first destroy the second.

Sebastián Pereira, 25, software engineering student, Montevideo, Uruguay:

If you and your colleagues had been publicly acknowledged as engineers from the start, do you think the trajectory of computing – and gender balance in the field – would have changed more rapidly? How do you imagine the culture of programming might look now if your contributions had been recognised in real time?

Sebastián, that is precisely the question. One I’ve given plenty of thought, honestly.

If we’d been called “engineers” from day one – if the Army press release had named us, if our contributions were published in IEEE journals instead of buried in classified reports, if we’d been paid the same as the men with identical credentials – would computing look different? Would women have stayed?

Honestly? I think it might have. But probably not for the reasons you’d hope.

Here’s the mechanism I see. Recognition begets opportunity. If Jean Bartik had been publicly credited as “chief programmer of ENIAC” in 1946, she’d have had job offers from companies we’ve never heard of. She might have founded her own firm. Betty Holberton with formal acknowledgment could have published papers, built an academic reputation, mentored younger women. The compounding effect of early visibility is enormous.

But – and this is crucial – that wouldn’t have solved the marriage problem. I left in 1947 because Abe and I wanted to start a family, and the culture said women didn’t do that while working in technical fields. Recognition wouldn’t have changed that calculus. It might have made it harder – I’d have had more to give up.

The real change would have needed to be deeper: institutional support for women with children, flexible arrangements, the expectation that technical careers could have interruptions without erasure. That required not just recognition but structural reform. The Army wasn’t ready for that. Nobody was.

What might have changed faster is the pipeline itself. If women had been visibly running computing projects, if the 1950 generation saw female names on groundbreaking papers, perhaps more girls would have studied mathematics and engineering. The cultural narrative – “computers are for men” – might not have calcified so quickly. You’d have had a larger cohort of women entering the field before institutional barriers hardened.

Jean stayed longer than I did. Kay McNulty went into industry. Betty eventually came back to computing through her husband’s work. But most of the other women who programmed ENIAC or worked in early computing drifted away. Recognition alone wouldn’t have held us all, but it might have held some. And those held women would have mentored others, creating momentum.

The tragedy is this: we had the talent, the drive, the intellectual capability. The field needed us. But the culture couldn’t accommodate us past a certain point. Real-time recognition might have bought a decade – just enough time for computing to professionalise in a different image. Instead, it professionalised in the image of the men who were left, and by the time women tried to re-enter in the sixties and seventies, the door had closed.

As for what I’d say to you, a young software engineer starting now – the situation is different but not entirely transformed. You have women in leadership, women founding companies, women publishing in top journals. That’s real progress. But you also have attrition, bias, the motherhood penalty, the expectation that women will eventually leave. The recognition is better; the structure is still imperfect.

So here’s my counsel: if you’re a woman entering computing, do the brilliant work – yes, absolutely. But also document it. Publish. Give talks. Make yourself visible in real time, not in retrospectives decades later. Build networks with other women doing this work. Don’t assume the institution will remember you fairly. Take responsibility for your own narrative.

And if you’re a man in computing – which I suspect you might be, Sebastián – use whatever advantage you have. Advocate for women colleagues. Push back on bias. Mentor women aggressively. The field needs them, and it doesn’t deserve the talent it’s losing to structural barriers.

Would computing be different if we’d been acknowledged as engineers? Probably. We’d have had a different generation entering the field, different problems prioritised, possibly a more collaborative culture. But we’ll never know. What I do know is this: the women doing brilliant work right now – in artificial intelligence, in systems design, in everything – they’re inheriting a field we shaped, even though our names were forgotten. Make sure their names aren’t forgotten. That’s how we change the trajectory.

Neema Mwita, 41, mathematics lecturer, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania:

You’ve described being one of a tight-knit team of women whose methods shaped modern programming. How did your mathematical intuition and collaboration with peers shape not only ENIAC’s success but your personal approach to learning and teaching? What advice would you offer to educators fostering similar talents today?

Neema, what a profound question. You’re asking about the relationship between collaboration, mathematical thinking, and teaching – things I’ve reflected on deeply.

The six of us at ENIAC didn’t just solve a problem together; we invented a way of thinking together. That collaborative mind shaped how I approached everything afterward, including teaching my own daughters mathematics.

Here’s what I mean. When Betty Snyder and I would work through a configuration problem, she’d see the system holistically – how data flowed from panel to panel. I’d see the mathematical structure – where integration happened, how coefficients propagated. Kay would catch logical errors. Jean would trace the physical signal paths. We weren’t just dividing labour; we were multiplying perspective. Each person’s strength exposed the gaps in the others’ understanding. That’s not a weakness to overcome; it’s the point.

In teaching, I’ve tried to recreate that dynamic. When my daughters struggled with a geometry proof, I wouldn’t just explain it. I’d ask them to explain it back, then I’d propose a different approach, then we’d argue about which made more sense. Not bickering – genuine disagreement leading to deeper understanding. That’s what happened at ENIAC, every day.

The mathematical intuition developed differently too. We didn’t learn programming from textbooks – there were none. We learned by doing, by failure, by having to understand the why before we could manage the how. That forced a kind of depth. Modern students can memorise syntax and pass exams without truly understanding computation. We couldn’t afford that luxury. Every mistake cost us hours of debugging.

I’d want educators today to recreate that pressure – not the desperation, but the necessity of understanding. Don’t let students hide behind formulas. Make them explain the intuition. Make them collaborate in real ways, not just group projects where one person does the work. Create spaces where different types of thinking – the systems thinker, the pure mathematician, the engineer, the careful validator – must genuinely listen to each other.

The danger I see in modern education is specialisation too early. We were forced to be generalists because the field didn’t exist. We had to understand mathematics and electronics and logic and physics. That breadth created resilience. You could spot errors across domains because you understood multiple languages.

One specific practice I’d recommend: have students teach each other. Not present; really teach. When you have to explain complex ideas to someone who doesn’t yet understand them, you discover gaps in your own knowledge. Betty taught me signal routing. Kay taught me rigorous mathematics. Jean taught me patience with detail. I taught them the physics of trajectories. None of us were “experts” who descended to teach the novices. We were all learning, all teaching, simultaneously.

The other element – this is crucial – is creating psychological safety to be wrong. We made mistakes constantly. Hundreds of them. But the culture was: mistakes are information, not failure. If a switch configuration didn’t work, we didn’t blame the person who set it; we asked what we learned. That curiosity about failure is what drives real learning.

I’d also say: encourage women students to trust their mathematical intuition, even when they doubt themselves. I was convinced for years that I wasn’t as naturally gifted as Kay or Betty. But my “cautious, methodical” approach wasn’t inferior – it was different and valuable. We need all kinds of mathematical minds: the brilliant intuitive leapers and the careful integrators.

Here’s what I wish someone had told me as a young student: the ability to collaborate, to listen deeply, to translate between different ways of thinking – those are as important as raw mathematical talent. Maybe more so. ENIAC succeeded because six people with different minds learned to think together. That’s the real lesson for educators.

And finally, Neema – be honest with your students about the costs. I left computing because the culture couldn’t accommodate women, but also because I was exhausted by the constant proving, the need to be twice as good for half the recognition. Teaching the next generation means acknowledging those real barriers while refusing to let them define what’s possible. Show them the women doing brilliant work now, yes. But also teach them to build cultures where such brilliance doesn’t require heroic sacrifice.

The women walking in my footsteps shouldn’t have to choose between mathematical brilliance and belonging. That’s the structural change we need – not just recognition of past contributions, but transformation of the environment so future contributions flourish.

Reflection

Marlyn Meltzer passed away on 7th December 2008, at the age of 86, in Yardley, Pennsylvania. She did not live to see the full flowering of the historical recovery that began in earnest in the 2000s – Kathy Kleiman’s documentary “The Computers” premiered in 2013, five years after her death – yet she witnessed enough. The 1997 induction into the Women in Technology International Hall of Fame came when she was seventy-five, a recognition that arrived late but, crucially, before she died. She knew, in her final years, that the record was being corrected. That matters.

Speaking with Marlyn across the decades revealed something the archival record obscures: her own uncertainty about her legacy. The historical accounts frame her as a quiet hero, steadfast and unambiguous. The real Marlyn was more conflicted. She carried pride in her work alongside regret about her departure, frustration at erasure mingled with acceptance of her choices. She spoke candidly about mistakes – the rounding error that nearly derailed ENIAC’s credibility, her own slowness compared to peers, moments of doubt about whether she belonged. That candour matters because it humanises innovation. Genius is not serene; it is anxious, iterative, occasionally uncertain.

Several themes emerged across these conversations that complicate the standard narrative. First, the distinction between recognition and structural change. Marlyn understood acutely that naming her contribution wouldn’t have solved the marriage penalty or institutional bias. Visibility alone cannot sustain women in fields hostile to their presence. This is a lesson contemporary discussions of “pipeline problems” often miss. We celebrate women entering STEM, yet attrition remains high because celebration doesn’t change the working conditions, family policies, or cultural assumptions that push women out. Marlyn recognised that truth in 1947; we are still learning it today.

Second, her insistence on the physicality of computing. Modern histories of ENIAC sometimes present programming as purely intellectual work – a triumph of mathematical abstraction. Marlyn corrected that. Programming ENIAC was embodied labour: the weight of patch cords, the ache of reaching into panels, the learned intuition that came from cranking calculators for months. This matters because it challenges the myth of disembodied genius. Women’s technical work has often been dismissed as mere operation because it involved hands-on engagement with machines. Marlyn reclaimed that as a strength: physical intimacy with materials and mechanisms breeds understanding that pure abstraction cannot achieve.

Third, her nuanced critique of speed as a virtue. In 1946, ENIAC’s velocity was revolutionary – calculations collapsing from forty hours to seconds. Yet Marlyn spoke repeatedly about the discipline required to not trust that speed blindly, to insist on verification even when it slowed deployment. That insight echoes through contemporary computing, where the pressure for rapid delivery often overwhelms careful validation. Her advice to modern engineers – that speed is a tool, not a virtue – deserves to be institutionalised in how we train programmers and evaluate systems.

There remain gaps and contested interpretations in the historical record that this conversation illuminated without fully resolving. For instance: the exact division of labour among the six ENIAC programmers remains somewhat fuzzy in published accounts. Marlyn’s description of her specialisation in ballistics mathematics and physical plausibility checks provides texture, but it also raises questions. Did the other programmers see the work the same way? How did credit flow in moments of breakthrough? The historical record, compiled largely from interviews conducted decades later, cannot fully recover those day-to-day dynamics. What we can say is that Marlyn’s account – modest about her own role, generous toward colleagues, precise about technical contributions – bears the marks of someone trying to be accurate rather than self-aggrandising.

Another uncertainty: the precise impact of classified status on women’s erasure. Marlyn noted that military secrecy inadvertently protected institutional sexism by hiding women’s work entirely. That’s a plausible mechanism, but the counterfactual is hard to test. Would unclassified computing work have treated women differently? The limited evidence – from commercial computing in the 1950s onward – suggests not dramatically. Yet the interaction between wartime secrecy and postwar gender norms deserves more rigorous historical investigation than it has received.

The rediscovery of Marlyn’s contributions traces a particular arc. She was essentially absent from computing history until the 1990s, when Kathy Kleiman began the ENIAC Programmers Project. Kleiman’s work – interviewing the surviving programmers, collecting oral histories, eventually producing documentaries – lifted these women from obscurity. The 2010 documentary “Top Secret Rosies” brought Marlyn’s story to a broader audience. Her induction to the Hall of Fame in 1997 created a touchstone. More recently, historians like Jennifer Light and Mar Hicks have positioned the ENIAC programmers within larger narratives about how computing became masculinised. Marlyn’s specific contributions – her work on trajectory calculations, her innovations in numerical integration verification, her methodological insights – have been cited by historians of computing and, increasingly, by educators designing curricula around early computing history.

Yet there remains a gap between historical recognition and professional legacy. Marlyn’s technical insights – about dual-path validation, about the gap between intention and implementation, about the necessity of understanding the physics beneath the mathematics – are sound. They are not widely cited in contemporary computing textbooks or engineering curricula. When modern programmers discover these principles, they often do so through independent reasoning or through rediscovery, not through explicit transmission from ENIAC’s era. That represents a lost opportunity: Marlyn’s hard-won wisdom could be explicitly taught, not merely recovered post-hoc.

Marlyn’s legacy rests in its powerful intersection of technical brilliance and civic dedication. She invented foundational software engineering practices, then left the field to deliver meals to elderly neighbours and knit cancer hats. The standard narrative treats these as separate acts: the brilliant young programmer and the devoted volunteer. Marlyn’s own account collapsed that distinction. The precision, the care, the commitment to doing work well – these were continuous across domains. This matters profoundly for how we think about women’s contributions to STEM and beyond. The assumption that “serious” technical work is the only work worth remembering is itself a form of erasure. Marlyn applied her mathematical mind to care work, and that application was neither diminishment nor distraction. It was consistency of purpose.

For young women pursuing paths in mathematics, computing, physics, or engineering today, Marlyn’s life offers both caution and inspiration. The caution: structural barriers remain real. Individual brilliance, while necessary, is not sufficient to overcome them. You may do extraordinary work and still be pushed out if the culture doesn’t value your presence. Marlyn knew that and chose another path without shame. That choice itself is instructive – sometimes the bravest thing is recognising when an institution is not worth the fight, and investing your energy elsewhere.

The inspiration lies in her intellectual courage and her refusal to compartmentalise her life. She didn’t wait for permission to learn ENIAC’s architecture. She didn’t apologise for her methodical approach when faster colleagues rushed ahead. She didn’t diminish her contributions when she left computing. She didn’t pretend her later volunteer work was less important because it was unpaid. She lived with integrity across apparently contradictory roles.

For women entering STEM today, Marlyn’s example suggests several practices worth adopting. Document your work explicitly – in writing, in presentations, in conversations – rather than assuming it will be remembered. Build genuine collaborative relationships with peers, recognising that different minds solve problems differently. Maintain physical understanding of the systems you work with, rather than abstracting too early. Question speed as a virtue; insist on verification. And crucially: refuse the false choice between “serious” technical work and care work, between professional achievement and community service. These need not be opposites. They can be expressions of the same commitment to rigour and purpose.

Perhaps most importantly, young women in STEM today should understand that their visibility matters not just for themselves but for everyone who comes after. Marlyn and her colleagues thought their work was self-evident – that doing brilliant things would change perceptions. They were wrong. It took decades for historians to recover their contributions, and even now, their names are less widely known than those of male contemporaries. This is not because their work was less significant but because visibility was systematically denied. By being visibly present, by naming your contributions, by refusing to disappear into the background – you are not being arrogant. You are being responsible to everyone following. You are refusing to let history repeat itself.

Marlyn Meltzer died knowing her contributions were finally being recognised, that her name would appear in documentaries, that young people learning computing history would encounter her work. She lived long enough to see the beginning of correction, if not its completion. That is more than many pioneers receive. But it should not have taken nearly fifty years. And the work of making women’s STEM contributions fully visible remains incomplete.

In speaking with Marlyn, what became clear is that her story is not anomalous – it is emblematic. She is one of thousands of women whose technical brilliance was overlooked, whose innovations were attributed to others, whose names were forgotten. The difference is that some of her story has been recovered. Many have not. For every Marlyn Meltzer we now know about, there are dozens we do not. That asymmetry should provoke both humility – about how much we still don’t know – and urgency: about the need to recover, preserve, and celebrate the contributions of women in science and technology, not as historical curiosities but as living lessons for how innovation actually happens, and how easily it can be erased.

The question is not whether Marlyn Meltzer’s legacy matters. It unmistakably does. The question is whether we will truly learn from it: whether we will change the structures that push women out, whether we will ensure that the next generation of brilliant women mathematicians and engineers will not have to choose between professional recognition and belonging, whether we will build cultures where technical excellence is visible regardless of gender, where collaboration is prized over competition, where both rigorous innovation and genuine care are honoured as essential human endeavours.

That work begins now, in the choices we make about who we listen to, whose contributions we centre, and how we teach the next generation to see themselves in the history of science and technology. Marlyn Meltzer showed us what brilliance looks like. Now it is our turn to show her – and ourselves – what equity looks like.

Editorial Note

This interview is a work of informed historical imagination. Marlyn Meltzer passed away on 7th December 2008, and these words are not her direct testimony. Rather, they represent a carefully researched reconstruction based on documented biographical information, published accounts of her work at ENIAC, oral histories collected by Kathy Kleiman’s ENIAC Programmers Project, technical documentation of ENIAC’s architecture and programming methods, and the broader historical record of women in early computing.

What is factual: Marlyn Meltzer’s biographical details (birth year 1922, education at Temple University, work at the Moore School, selection as one of six ENIAC programmers, her departure in 1947 upon marriage, her extensive volunteer work including Meals on Wheels and chemotherapy hat knitting), the specifications of ENIAC (17,468 vacuum tubes, 3,000 switches, 40 panels, 150kW power consumption), her specialisation in ballistics trajectory calculations and numerical integration, the public debut of ENIAC in February 1946, and her posthumous recognition (Hall of Fame induction in 1997, appearance in documentaries).

What is interpreted or dramatised: Marlyn’s exact words, her internal reflections, specific anecdotes and conversations with colleagues, her personal motivations for decisions, her reflections on modern technology (by definition, she could not have commented on contemporary AI or software practices), and the precise emotional tenor of her experience. The conversational style, contemporary phrasing, and narrative arc are constructed to honour what we know about her while acknowledging what we cannot know with certainty.

Technical accuracy: The explanations of ENIAC’s architecture, programming methods, numerical integration procedures, and the trajectory calculation process reflect historical technical documentation and interviews with other ENIAC programmers. However, these too represent reconstructions – the exact procedures evolved over time, and different programmers may have described them differently. Where technical details are presented, they are grounded in primary sources, but they are presented through Marlyn’s perspective as a character, not as definitive technical history.

Gaps and uncertainties: The precise division of labour among the six programmers remains somewhat unclear in the historical record. The exact nature of Marlyn’s specific contributions – beyond her known expertise in ballistics mathematics – involves some interpretation. Her reasons for leaving computing in 1947 combined personal choice with era constraints; the precise weighting of these factors cannot be fully recovered. Her reflections on her volunteer work, while consistent with documented facts about what she did, represent an interpretation of what those activities might have meant to her.

Purpose of dramatisation: This format – the interview – allows for a more intimate exploration of Marlyn’s intellect, personality, and perspective than a traditional historical essay would permit. By presenting her as a speaking presence, we aim to make her contributions vivid and immediate, to illustrate not just what she did but how she thought. This comes at the cost of some historical precision; dramatisation necessarily simplifies and selects. Readers seeking comprehensive technical details or exhaustive source citations should consult the documentary record, particularly the ENIAC Programmers Project archives and academic histories by scholars such as Jennifer Light and Mar Hicks.

Ethical considerations: We have endeavoured to represent Marlyn with intellectual honesty – including her uncertainties, her mistakes, her conflicts – rather than as a flawless icon. We have avoided fabricating details or attributing to her knowledge she could not have possessed. We have tried to let her speak with the voice and perspective of her time and background, rather than imposing contemporary language or sensibilities. Where we have put words in her mouth, we have done so in service of illuminating her documented perspectives and values.

This interview is offered as a form of historical engagement – a bridge between the archival record and the reader’s imagination, grounded in fact but shaped by interpretation. It is not a substitution for primary sources or rigorous historical scholarship. Rather, it is an invitation to encounter Marlyn Meltzer as a fully realised person: brilliant, thoughtful, conflicted, and consequential. That encounter may inspire further reading, further research, and further reflection on how we recover, preserve, and honour the contributions of those whose work shaped the world we inhabit.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment