Sunday, 6th November 1870 – Paris

The bells of Saint-Sulpice called through fog this morning, their sound muffled as though the very air conspired to dampen hope. I made my way through streets emptied of all but those drawn by habit or hunger to the doors of the church. Inside, the nave was colder than the pavements without – we are burning what little fuel remains in our lodgings, and God’s house must wait upon man’s necessity.

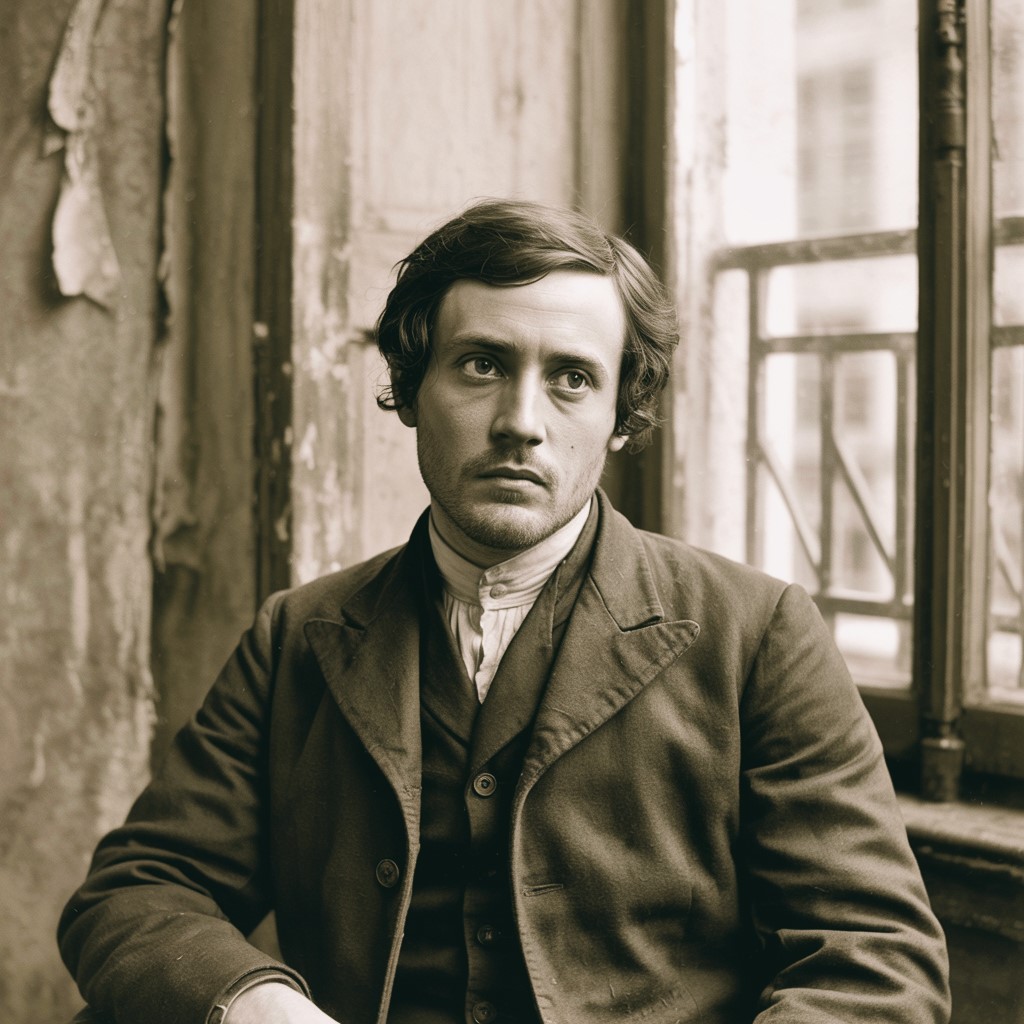

The congregation wore the grey mask of siege upon every countenance. Madame Rouxel with her threadbare shawl, the conscript still bearing powder-stains upon his collar, the butcher who last month sold mutton and this week offers cat. Their faces might have been carved upon a rood-screen, so fixed and hollow had want rendered them. Even the plaster saints seemed to regard us with reproach, their painted visages chipped where damp has crept behind the gilt. I thought of the death-masks one sees in the museums – that peculiar stillness which suggests the soul has fled, leaving only the husk of feature and bone.

Father Dubreuil spoke of Metz. The fortress has fallen; twenty thousand of our men march now into German captivity. He did not say so plain, but we understood. The homily turned upon the trials of the Israelites, their wandering, their bondage. I confess my mind strayed. The incense curling upward seemed to take the shape of towers and bridges I have not seen these fifteen years – the arch at Rouen, the lime-trees at Lyon where I spent a summer before the troubles. Strange how the mind, confined, takes flight where the body cannot. My nights are thick with visions: I stand upon the ramparts and watch balloons ascend into darkness, bearing letters I can never send. I see my mother’s kitchen, the blue tiles about the hearth, the copper pans catching October sun. I wake to rat-scratching in the wainscot and the rumble of cannon from the eastern forts.

The rubric speaks of preparing a place, of mansions and of rest. I wonder if the Almighty permits such rest to those who live half in dream, half in waking dread. Gambetta escaped by balloon – so the papers report – on the seventh of last month, floating above Prussian lines to raise the provinces. We place faith in such phantoms: a man in a wicker basket, borne by gas and fortune, becoming Minister and hope entire. It is the stuff of romances, yet we are reduced to romances now.

After the Mass concluded, I lingered near the confessional. Someone asked me once – in another life, it seems – how I manage the time I spend before screens. I thought little of it then. Now I see I have spent much of this siege at one screen or another. The confessional grille, where I have unburdened sins both ancient and immediate, becomes a barrier that paradoxically grants closeness to absolution. The iron grilles upon the windows of my lodging permit a view of the street but cage the view in bars, so that I watch the world in neat squares, like a chessboard upon which I am no longer permitted to move. Even the rood-screen here at Saint-Sulpice divides the chancel from the nave, the sacred from the profane, and I find myself kneeling there longer each Sunday, as though proximity to that boundary might grant passage through.

Yet the most insistent screen is the one I carry within – the veil my imagination throws across every waking hour. I ration my dreams as carefully as we ration bread. Too much time spent in reverie renders one unfit for the narrow duties that remain: queuing for black bread, avoiding conscription officers, reading aloud to old Monsieur Troadec whose eyes have failed. But too little, and the soul withers. I permit myself an hour each evening by candlelight – no more – to sit and conjure the faces of those I have lost, the places I may never see again, the conversations that ended mid-sentence when the armies came. It is a dangerous economy, this management of the interior life. One may grow prodigal and lose oneself entire; or miserly, and lose what makes the losing worthwhile.

The afternoon brings rumours of fighting near Orléans. The war is not yet lost, they say. I find I can no longer distinguish rumour from wish, news from fever-dream. The mask we present to one another in the bread queue is courage; beneath it, we are hollow as the saints.

I shall sleep poorly again tonight, I think.

Pierre Auguste Rousseau

Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). By early November 1870, Metz had capitulated to Prussia, sending tens of thousands of French soldiers into captivity, while Paris remained under siege from 19th September with severe shortages and balloon post maintaining communication. The conflict, sparked by tensions over the Spanish succession and German unification, saw Prussian-led forces decisively defeat the French Second Empire, leading to Napoleon III’s fall and the proclamation of the French Third Republic. Paris would endure bombardment and hunger through winter, capitulating in January 1871; the Treaty of Frankfurt followed in May, ceding Alsace and parts of Lorraine to Germany. The upheaval contributed to the Paris Commune in spring 1871.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment