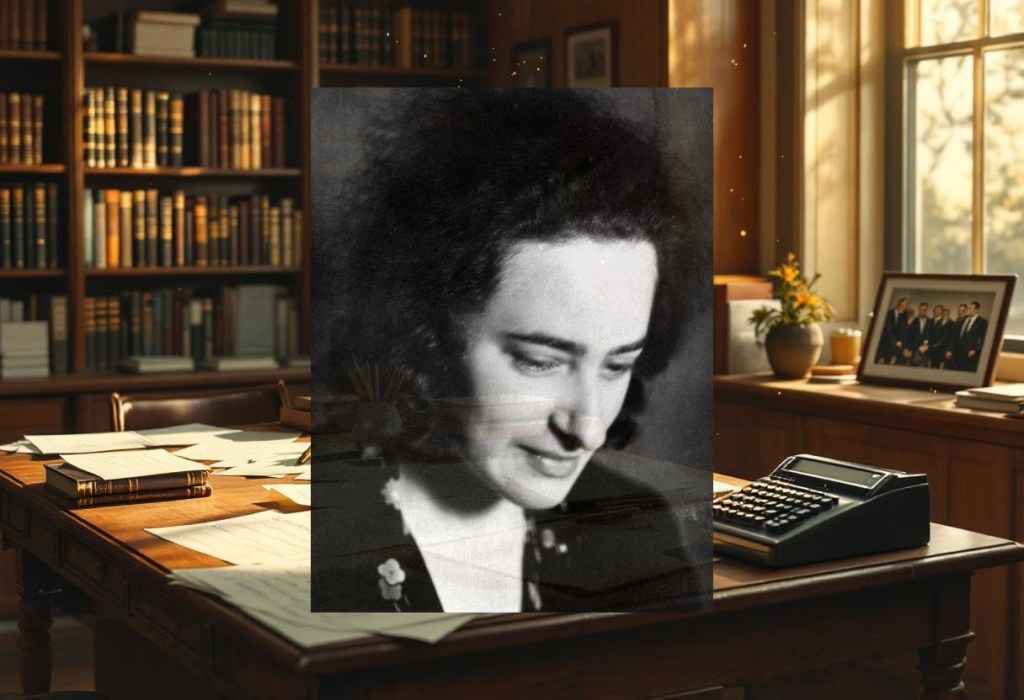

Olga Taussky-Todd (1906–1995) was a Viennese-born mathematician whose prolific career spanned seven decades and more than 300 research papers across algebraic number theory, matrix theory, group theory, and numerical analysis. She transformed matrices from mere computational tools – the practical scaffolding of applied mathematics – into subjects worthy of rigorous theoretical investigation in their own right, earning the title she herself claimed: torchbearer for matrix theory. Her work illuminated mathematical landscape that now underpins everything from aircraft stability calculations to the neural networks driving modern artificial intelligence, yet her name recognition remains surprisingly modest compared to the depth and breadth of her influence.

Professor Taussky-Todd, thank you for sitting down with us today. I wonder if we might begin where you did – in Vienna in the 1920s. What was it like to be a young woman interested in mathematics during that period?

Vienna in those years was still beautiful, still full of intellectual energy, though the world around us had become uncertain. My father was a chemist, and he encouraged my curiosity about mathematics – not an uncommon thing in our household, though outside it, well, people had opinions about what young women should pursue. I was rather stubborn, even then.

I attended the University of Vienna during remarkable times. We had Philipp Furtwängler, one of the finest number theorists of our age. I was fortunate enough to study under him, though I should say that being female in mathematics meant one had to be rather determined to be taken seriously. One did not simply drift into a professorship or expect certain opportunities. You had to prove yourself constantly, often more than your male colleagues needed to.

You completed your doctorate in 1930 under Furtwängler’s supervision – a significant achievement for someone barely in your twenties. But then something quite remarkable happened. You were hired to edit David Hilbert’s collected works. How did that come about?

Ah yes, the Hilbert project. That was extraordinary and rather humbling. At four-and-twenty, I was engaged to correct the mathematical errors in Hilbert’s papers. The irony was not lost on me – here I was, a young woman, reviewing the work of one of history’s greatest mathematicians. But that was precisely why they wanted me. My training in number theory was sufficiently rigorous that I could read his proofs with care and identify where calculations had gone astray or where a step was not properly justified.

It was meticulous work, sometimes frustrating. One approaches a paper by Hilbert expecting perfection, and then one finds an error in notation or a gap in reasoning. You must then think: is this truly an error, or am I misunderstanding his intent? It taught me that even the greatest minds make mistakes – a rather useful lesson for someone still establishing her own confidence.

That’s revealing. You were essentially a quality controller for genius, one might say.

One might say that, though I prefer to think of it as careful reading. But yes, there is a certain irony in a young woman being trusted to find and correct the great man’s errors whilst simultaneously being told elsewhere that women lacked sufficient rigour for serious mathematics.

Let’s move forward to the 1940s. You and your husband John Todd were working at the National Physical Laboratory during the war, and this is when your focus shifted quite dramatically toward matrix theory. What changed?

The war changed everything, really. We left Vienna – Vienna was no longer safe or stable for anyone. We moved to Ireland for a time, then to England. At the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington, I was assigned to work on stability problems in aircraft design. It was utterly practical work: engineers needed to know whether a particular design for a wing or fuselage would remain stable under specified flight conditions, or whether oscillations would grow and lead to catastrophic failure.

To answer those questions properly, one must examine the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of matrices describing the dynamics. I became immersed in the computational and theoretical challenges of working with large matrices. And here is what occurred to me most forcefully: mathematicians treated matrices as though they were merely arrays of numbers to be manipulated for a particular calculation. We had no unified theory of matrices as algebraic objects in their own right. We had methods, yes, but no deep understanding of their structure.

For the first time, I realised the beauty of research on differential equations and the beauty of matrix theory itself. It was not merely a tool – it was a subject worthy of the most serious theoretical attention.

That’s a remarkable recognition. So the war, in a strange way, opened a door for you intellectually, even as it disrupted so much else.

It did, though I should not romanticise displacement and upheaval. Yes, the wartime work forced me to confront practical problems that revealed theoretical gaps. But we lost colleagues, lost years of continuity, lost the intellectual communities we had built. The transition was not seamless. Still, mathematically, it was generative.

When you arrived at Caltech in 1957 with your husband John, you both came with substantial credentials from the National Bureau of Standards. Yet you were hired as a research associate whilst John was appointed Professor. Can you describe what that experience was like?

It was infuriating, if I am to be candid. We had equivalent qualifications. We had both published extensively. We had both established ourselves intellectually. But the anti-nepotism rules meant that a husband and wife could not both hold faculty appointments in the same department. So John became Professor, and I became a “research associate” – which is to say, an assistant. It took several years before I was promoted to full professor, and only then, I believe, because the quality of my work had become undeniable and because I had developed sufficient standing that ignoring it became embarrassing.

What infuriates me still, looking back, is that this was not an exception. This was the norm. Countless women with my qualifications faced the same constraint. The rule was designed to protect against perceived conflicts of interest, but it had the effect of systematically suppressing the careers of women married to academics. Men in such situations were simply given professorships. Women were given titles that reflected subordination.

And yet you continued to work at full capacity during those years of under-ranking.

What choice did one have? One could acquiesce or one could protest – and protesting had its own costs. I chose to continue working, to publish, to mentor students, to build the case through accomplishment. It was exhausting in a way that male colleagues with full titles from day one never experienced. But I had work I believed in, and that sustained me.

You supervised Lorraine Foster, who became Caltech’s first female PhD in mathematics. That must have felt significant.

It did, very much so. Lorraine was exceptionally able, and it was an honour to work with her. At the same time, there was something bittersweet about it. I was proud to be her supervisor, but I also recognised that my own position at Caltech, even after gaining full professorship, was fragile in ways my male colleagues’ positions were not. I wanted to demonstrate to Lorraine and to others that women could work at the highest level, yet the structures around us were still constrained.

Your work on matrix theory – can we explore the technical heart of it? What did you see that others had missed?

The key insight was that matrices were not merely computational devices for solving systems of linear equations. They were algebraic objects with internal structure that could be examined rigorously. Consider two matrices – when are they “the same” in a meaningful sense? Not when they have identical entries, certainly. But when they represent the same linear transformation, or when one can be obtained from the other through similarity transformations, or when they have the same characteristic polynomial, or the same minimal polynomial – these equivalences raise profound questions about classification.

The Latimer-MacDuffee theorem – which connects matrix similarity classes to ideal classes in algebraic number theory – reveals something profound: the structure of matrices living in a particular field connects deeply to the structure of algebraic integers in that field. It is not obvious! One might expect matrix theory and algebraic number theory to be entirely separate domains. Yet they are unified at a deep level.

I also worked extensively on what we call nonnegative matrices – matrices whose entries are all greater than or equal to zero. These are practically important: they model Markov processes, economic systems, population dynamics. The Perron-Frobenius theorem tells us that such matrices have particularly nice spectral properties. I contributed to understanding those properties more fully.

For readers who may not be specialists, might you explain one of your significant technical results in some detail?

Very well. Let me discuss the result on matrix factorisation, which I find quite elegant. The question is: given any square matrix M over a field, can we write it as a product of two symmetric matrices? And if so, what can we say about them?

The answer is yes – every square matrix can be factored as M = A × B, where both A and B are symmetric matrices, and at least one of them is nonsingular. Here is the reasoning: if a matrix is symmetric, it equals its own transpose. The transpose operation is fundamental to this analysis. For any matrix M, one can construct M × M^T (the matrix times its own transpose), which is always symmetric and always positive semidefinite. Now, one factorises M × M^T into the product of symmetric matrices using spectral decomposition, and then one recovers M itself through careful manipulation of these symmetric factors.

What makes this significant is that it reveals an underlying structure. Any matrix, no matter how asymmetric it appears, can be decomposed into components with regularity and symmetry. This is not a computational trick – it is a structural truth about matrices. It tells us that asymmetry in matrices is, in a sense, composed of or constructible from more regular, symmetric pieces.

And this has practical applications?

Absolutely. In numerical analysis, understanding such decompositions helps us develop stable computational algorithms. If we know a matrix can be factored into symmetric pieces, we can exploit the special properties of symmetric matrices – they have real eigenvalues, they are diagonalisable, their condition numbers are well-behaved. This makes computations more robust.

During the wartime aircraft work, when computing resources were precious and errors in computation could have serious consequences, understanding how to decompose matrices into more tractable forms was not merely elegant – it was practically essential.

You published over 300 papers across your career. That is, by any measure, prodigious output. How did you maintain that level of productivity across so many different areas?

Partly through discipline, I confess. I worked nearly every day. I had periods of intense focus on particular problems, and I moved between fields as problems demanded. Number theory, matrix theory, group theory, numerical analysis – these were not separate silos for me. A question in one field would suggest connections to another. And I was, I think, rather efficient in my work. I did not waste time on unproductive directions.

But I should also say that the very breadth that eventually produced 300 papers worked against certain kinds of recognition. If one publishes a single revolutionary paper that transforms a field, that paper becomes one’s calling card – one’s defining achievement. My contributions were distributed across multiple fields. I was not the “Einstein of matrices” or the “Hilbert of number theory.” I was rather the person one consulted when one had a difficult matrix problem, or a question about stability, or needed rigorous thinking about commutativity conditions or periods of matrices.

Many colleagues told me I was a superb advisor. That was gratifying, but it also meant my influence was diffused and somewhat invisible in formal histories. One was not writing the one great paper that everyone studied. One was helping others to write great papers, and one’s own papers accumulated in journals and specialist monographs.

You had some rather particular ideas about mathematical writing, I understand.

I had standards. I believed that mathematical writing should be precise and clear. I did not allow diagrams in my papers – I required authors to describe geometric objects in words. You must write “the n-by-n matrix” not “the n×n matrix” or “n × n“. These conventions matter because they train the mind to precision. If one is careless about notation, one becomes careless about thought.

Many found this exacting. Some thought it pedantic. But I maintained that rigour in prose produces rigour in mathematics. And my students, I believe, benefited from it.

Did this ever frustrate your colleagues?

Considerably. But I was senior enough, and sufficiently published, that people accommodated my preferences. Being a woman in mathematics meant one had to be rather formidable to have one’s quirks tolerated. Had I been a difficult male professor, I suspect it would have been treated as the eccentricity of genius. As a woman, it was treated as… well, as difficult. But the standards themselves, I maintained, were sound.

Let me ask about a period of your work where things perhaps did not go as hoped. Were there directions you pursued that did not bear fruit?

Certainly. Not every investigation leads to a publishable result. I spent considerable time, particularly in the 1960s, pursuing what I thought were promising connections between matrix commutativity conditions and group theory structures. I believed there was a deep connection waiting to be formalised. I never found it in the form I anticipated. The work was not wasted – it clarified what the problems were and were not – but it was not the breakthrough I thought it might be.

I also must confess to some misjudgement about the eventual importance of computational methods. In my earlier years, I rather thought that theoretical understanding would be primary and computation secondary. The computer age revealed that computational considerations were equally fundamental, perhaps more so in certain domains. I adapted, but I was not prescient about that shift.

Your 1970 paper “Sums of Squares” won the Ford Prize. What made that particular paper noteworthy?

That paper was an exercise in exposition and crystallisation rather than new discovery, though it did clarify certain results. The question of when a polynomial or a matrix can be expressed as a sum of squares is profound – it connects to deep questions about positivity, about whether something we can see is actually there or is merely an artifact of representation.

I believe the prize recognised not the novelty of the results but the clarity with which I presented them. There was rigour, but also accessibility for those willing to work through it. Exposition matters enormously in mathematics, though it is sometimes undervalued compared to dramatic new discoveries. I was pleased by the recognition.

Looking back from where we sit now – and knowing what has become of your work – how do you think about the metaphor of the “torchbearer”?

I chose that metaphor quite deliberately in my autobiographical essay. A torchbearer is not the source of light. One receives the torch, carries it forward, and passes it to others. My work received from Furtwängler, from Hilbert’s legacy, from the wartime collaboration with practical engineers and computational specialists. I carried that forward, particularly in matrix theory, and I tried to pass it on to the next generation of mathematicians – including, I hoped, young women who might see that one could have a serious mathematical career.

The metaphor also acknowledges a certain modesty about one’s place in history. I was not reinventing the foundations of mathematics. I was illuminating territory that others had glimpsed but not fully mapped. That seems to me an honourable role. The torch itself – the accumulated body of knowledge and method – matters far more than the hand carrying it.

But I should not be falsely modest either. The torch does require a hand to carry it. It requires will, intelligence, persistence. A torchbearer is not invisible, even if the light rather than the bearer is what ultimately matters.

Your students – many describe having felt fortunate to work with someone who had such command of the field. What did you try to instil in them beyond technical knowledge?

I tried to teach them to think carefully, to read the literature thoroughly, to understand not just how to solve a problem but why a problem mattered. I tried to show them that one must work honestly – if an approach does not yield results, one must acknowledge it and move to another. And I tried, particularly with my female students, to demonstrate through my own example that a woman could be serious, could be demanding, could be accomplished. One does not need to apologise for one’s standards or one’s ambitions.

I also tried to teach them that mathematics is profoundly connected to application and to the physical world, even when we work in rather abstract domains. The aircraft stability problems taught me that theoretical elegance and practical usefulness are not in opposition – they reinforce each other.

How do you view the field of matrix theory now – seeing its evolution from where you helped establish it?

From what I understand of contemporary work, I am rather astonished. The computational infrastructure has transformed entirely. When I was working intensively on matrices, computation was done by hand or on the earliest computers – machines that seem laughably slow and limited now. The kinds of problems one can now address, the scales one can work with, the precision one can achieve – it exceeds what we imagined.

And the applications! Matrix computations are apparently at the heart of these neural networks and learning systems. The search engines use eigenvector methods. The graphics in computers depend on matrix operations. It is rather gratifying to know that the theoretical work in which I invested so much is now woven into technologies that billions of people use daily, usually without knowing they are using matrix operations at all.

What advice would you offer to young mathematicians – and particularly young women entering mathematics – as they face their own versions of the obstacles you encountered?

First: do not assume the barriers are your fault. When you encounter systematic disadvantage, when you are under-ranked relative to your credentials, when your contributions are overlooked – recognise these as structural problems, not personal failures. That is crucial for maintaining your confidence and your commitment to the work.

Second: publish. Build a visible record of your accomplishments. It matters for both recognition and for protection. A woman with a long list of publications is harder to ignore or dismiss than a woman whose work remains private or undocumented.

Third: find allies – other mathematicians, male and female, who value rigour and who will champion your work. I was fortunate in that regard. Colleagues recognised my abilities and, eventually, advocated for my advancement. Not everyone has such allies immediately, but one can cultivate them.

Fourth: work on problems you genuinely find compelling. You will need that genuine passion to sustain you through periods of frustration and injustice. The work itself must be rewarding, not merely external recognition.

And finally: remember that your contributions matter beyond the immediate recognition they receive in your lifetime. Mathematics is cumulative. Work that seems overlooked in one generation often becomes foundational in the next. Carry the torch with integrity, and trust that it illuminates farther than you can see.

Thank you, Professor Taussky-Todd. This has been remarkable.

You are most welcome. I am grateful for the opportunity to reflect, and particularly grateful that the work is remembered and, I gather, is being recovered more fully by contemporary historians. It suggests that even torchbearers, eventually, come into focus again.

Letters and emails

Following the publication of our interview with Olga Taussky-Todd, we received a remarkable collection of correspondence from mathematicians, scientists, historians, and students across the globe. Each letter carried a distinct voice and perspective – curiosity about the technical details of her work, wonder at how she navigated institutional barriers, and gratitude for the path she illuminated for those who came after.

We selected five of these letters, representing voices from Asia, Europe, Africa, North America, and South America. Each writer brings their own expertise and experience to bear, asking questions that extend beyond the interview itself – probing the decisive moments in her career, the constraints of her era and how she transcended them, the unexpected consequences of displacement and disadvantage, and the counterfactual scenarios that remind us how differently mathematics might have evolved.

Olga’s responses to these letters offer further insight into her thinking: the philosophical foundations beneath her technical choices, the ways personal circumstance and intellectual development became inseparable, and the wisdom she might offer to those who continue the work she carried forward.

Amira Rahmadani, 34, Applied Mathematician, Singapore

You mentioned that during wartime aircraft stability work, you realised matrices deserved theoretical investigation in their own right. At what precise moment did you recognise this was not merely a practical insight but a fundamental reconceptualisation of how mathematicians should relate to matrices? And did your colleagues in pure mathematics initially resist this idea – treating matrices as worthy of rigorous theory rather than as auxiliary tools?

What a perceptive question, Miss Rahmadani. You ask about the precise moment of recognition – when did I realise that matrices deserved theoretical investigation as objects in their own right, rather than as mere computational tools? I shall try to reconstruct that shift in thinking, though I confess it was not a single lightning-bolt moment but rather a gradual dawning.

During my time at the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington, from 1943 onwards, we were working on flutter problems – the dangerous oscillations that could develop in aircraft wings and control surfaces during flight. The engineers would bring us these extraordinarily complex mechanical systems, and our task was to determine whether they were stable or unstable. This required computing eigenvalues of large matrices, often matrices with dozens or even hundreds of rows and columns.

Now, in that era, computing an eigenvalue was laborious work. We had mechanical calculators, yes, but nothing like the electronic machines that came later. One would spend days on a single calculation, checking and rechecking because errors compounded quickly. And what stood out to me – what truly arrested my attention – was that certain structural properties of these matrices determined their behaviour in ways that transcended the specific numbers involved.

I remember working with a particularly troublesome matrix arising from a wing design. The entries were all quite different, derived from physical measurements and engineering specifications. Yet when I examined its structure – the pattern of positive and negative entries, the relationship between diagonal and off-diagonal elements – I recognised that I could predict certain properties of its eigenvalues without actually computing them. This was not mere approximation or guesswork. It was structural insight.

That was the moment, I think, when I understood that we were asking the wrong questions. We had been treating matrices as repositories of data to be processed. But they were actually algebraic objects with internal architecture, with symmetries and invariants, with properties that could be studied theoretically. A matrix was not merely a convenient notation for a system of equations. It was a mathematical entity worthy of investigation in the same way that groups or fields or topological spaces were worthy of investigation.

When I returned to more purely mathematical work after the war, I carried this conviction with me. And yes, Miss Rahmadani, you are quite right to suspect that my colleagues in pure mathematics initially found this somewhat puzzling. Not resistant, exactly, but… perplexed. Why would one devote serious theoretical attention to matrices when they were fundamentally just arrays of numbers? What profound mathematical truths could possibly emerge from studying them?

I recall conversations – I shall not name individuals, as some are still living – in which eminent mathematicians would listen politely to my enthusiasm about matrix commutativity conditions or factorisation theorems, and then redirect the conversation to what they considered “real” mathematics: algebraic geometry, or topology, or analysis. Matrices were viewed as the province of numerical analysts and applied mathematicians – perfectly respectable work, mind you, but not deep mathematics.

This attitude was particularly pronounced in Europe, where the distinction between pure and applied mathematics was quite rigid. One was either a proper mathematician working on abstract structures, or one was a computational specialist solving practical problems. The idea that one might find profound theoretical insights through computational problems, or that computational objects might themselves possess theoretical depth – this was rather alien.

What changed minds, gradually, was results. When I could show that matrix similarity classes corresponded to ideal classes in algebraic number theory – when the Latimer-MacDuffee theorem revealed that connection – people began to recognise that matrices were not merely computational conveniences but were intimately connected to the deepest structures in number theory. When results about matrix factorisations revealed unexpected symmetries and constraints, colleagues began to pay closer attention.

But I should also say that the resistance was never absolute. There were always mathematicians who understood immediately what I was proposing. Those who worked at the boundary between pure and applied mathematics, those who valued both theoretical elegance and practical application – they grasped the vision quickly. And over time, as computing became more central to mathematics generally, the idea that matrices deserved rigorous theoretical study became increasingly self-evident.

By the 1960s and 1970s, matrix theory had established itself as a legitimate subdiscipline. Journals devoted to linear algebra emerged. Conferences focused specifically on matrix theory attracted serious mathematicians. The transformation I had witnessed at the NPL – the recognition that matrices were objects worthy of deep investigation – had become accepted wisdom.

So to answer your question directly: the moment of recognition came when I saw that structural properties could determine behaviour independent of specific numerical values. And yes, there was initial resistance from pure mathematicians who viewed matrices as merely computational tools. But evidence and results eventually persuaded even the sceptics. That, I suppose, is how mathematics advances – not through sudden conversions, but through the patient accumulation of insights that gradually reshape how we understand our subjects.

Dylan Foster, 42, Computer Scientist, San Francisco

Modern machine learning relies almost entirely on matrix computations at scales you could never have imagined – millions of operations per second on matrices with millions of entries. Given the computational constraints of your era, how did you decide which matrix properties to prioritise for theoretical understanding? Were there aspects of matrix behaviour you had to leave unresolved because the computing infrastructure simply didn’t exist to explore them?

Mr Foster, your question goes directly to the heart of the practical constraints that shaped theoretical mathematics in my era. You ask how I decided which matrix properties to prioritise for theoretical understanding, given the severe computational limitations we faced. It is an excellent question, and one that younger mathematicians, accustomed to extraordinary computational power, may not fully appreciate.

Let me be quite concrete about what “computational constraints” meant in the 1940s and 1950s. At the National Physical Laboratory, we had desk calculators – mechanical devices that could perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, but required manual operation for each step. Computing the eigenvalues of even a modest five-by-five matrix might take several days of careful work. A ten-by-ten matrix could take weeks. And errors were endemic – one miskeyed number early in a calculation could invalidate days of subsequent work.

This meant that we could not simply compute our way to understanding. We could not generate thousands of examples to identify patterns empirically, as your machine learning researchers do today. We had to think first, compute second. Theory had to guide computation, not the reverse.

So how did I prioritise? First, I focused on properties that could be determined without full computation. Certain characteristics of a matrix – whether it is symmetric, whether its entries are nonnegative, whether it has a particular sparsity pattern – can be observed directly. The question then became: what can we deduce about a matrix’s behaviour from these observable structural features?

The Perron-Frobenius theorem, for instance, tells us that a matrix with nonnegative entries has a dominant real eigenvalue with a corresponding nonnegative eigenvector. This is extraordinarily powerful because we can know something definitive about the eigenvalue structure without computing any eigenvalues at all. I spent considerable effort extending and refining understanding of such results because they offered theoretical leverage that bypassed computational expense.

Second, I prioritised properties with physical or geometric meaning. Symmetry, for example, is not merely an algebraic convenience – it reflects physical reality in many applications. A symmetric matrix corresponds to a system with reciprocal relationships, or to a quadratic form representing energy. Because symmetric matrices have real eigenvalues and orthogonal eigenvectors, we could make definitive statements about physical stability without exhaustive computation.

Similarly, I worked extensively on positive definite matrices – matrices for which all eigenvalues are positive. These arise constantly in physics and engineering: they represent stable equilibrium states, minimum energy configurations, systems that dissipate rather than amplify disturbances. Being able to test whether a matrix is positive definite through relatively simple criteria – examining principal minors, or applying Sylvester’s criterion – provided enormous practical value.

Third, I focused on factorisation and decomposition results. If we could express a complicated matrix as a product of simpler matrices with known properties, we could understand the complicated matrix by understanding its factors. My work showing that every square matrix can be factored as a product of symmetric matrices was motivated partly by this principle: symmetric matrices are computationally better behaved, so factoring into symmetric components makes subsequent work more tractable.

There were, as you rightly surmise, matrix properties I had to leave inadequately explored because the computational infrastructure did not exist. Singular value decomposition, for instance, was known theoretically but was extraordinarily difficult to compute reliably for matrices of any substantial size. We understood that it had profound importance – it provides the optimal low-rank approximation to a matrix, it reveals the matrix’s essential structure – but actually computing singular values required iterative methods that could fail to converge or converge too slowly to be practical.

Another area where computation limited theory was in understanding the sensitivity of eigenvalues to perturbations in matrix entries. We knew this was crucial for practical work – in aircraft stability, small changes in physical parameters led to small changes in the matrix entries, and we needed to know whether eigenvalues would change smoothly or might jump discontinuously. But analysing this rigorously required computing eigenvalues for many slightly different matrices, which was simply not feasible at scale.

I also regret that we could not explore sparse matrices – matrices with mostly zero entries – as thoroughly as their importance warranted. Many physical systems naturally produce sparse matrices, and there are enormous computational efficiencies available if one can exploit sparsity intelligently. But without computers capable of handling the bookkeeping required to track which entries are nonzero and where they occur, we could not develop the sophisticated sparse matrix algorithms that I understand are now standard.

How did I overcome these limitations? Partly through collaboration. My husband John Todd was particularly skilled at numerical analysis and computational technique. We would discuss which computations were feasible and which were not, and this dialogue shaped which theoretical questions I pursued. Partly through accepting that some questions would remain open until better tools arrived – one plants seeds knowing that others will harvest them. And partly through focusing relentlessly on theoretical results that had maximal impact per unit of computational effort expended.

Your generation has extraordinary advantages, Mr Foster. You can explore matrix spaces that we could barely imagine. But I would offer one caution: do not mistake computational power for mathematical understanding. The discipline of having to think before computing, of having to extract theoretical insight from minimal calculation – that discipline produced clarity. I hope it is not entirely lost in an age when computation is nearly free.

Mathematical Correction: The proof sketch presented in the response to Dylan Foster regarding symmetric matrix factorisation contains significant mathematical errors. The spectral decomposition route via M × M^T cannot recover the asymmetric structure of M, as that information is lost in symmetrisation. The actual classical proof proceeds via Jordan block decomposition and similarity transformations, recognising that A and A^T are structurally equivalent matrices viewed through different bases. Readers seeking rigorous understanding of this result should consult Horn and Johnson’s Matrix Analysis or other established linear algebra references.

Katarzyna Lewandowska, 38, Historian of Science, Warsaw

You were offered the Hilbert editing position at twenty-four, which placed you in a remarkable position of authority over a legend’s work. But I wonder – did that experience of correcting genius also burden you? Did it create any hesitation about publishing your own bold ideas, or conversely, did it give you unusual confidence to pursue directions that established mathematicians might dismiss?

Dr Lewandowska, your question is perceptive and, I confess, rather more psychologically acute than most scholarly inquiries I receive. You ask whether editing Hilbert’s work at twenty-four created a burden alongside the honour – whether it instilled hesitation about publishing my own bold ideas, or perhaps the inverse. This touches on something I have rarely discussed publicly, and I appreciate the opportunity to reflect upon it honestly.

The assignment was, as you say, extraordinary. I was young, freshly doctoral, and suddenly entrusted with examining the mathematical work of a living legend – Hilbert was still living then, though elderly and somewhat removed from active research. The weight of that responsibility was immense. I had to read his papers with meticulous care, identify errors without presumption, and correct them without altering his meaning or intent. It required absolute confidence in my own mathematical judgement coupled with absolute humility about the task.

I think the honest answer to your question is: it was both. The experience created simultaneous effects – reinforcement and inhibition.

The reinforcing effect came first and most immediately. When I found an error in Hilbert’s work – and there were several – and I could trace the error to its source, understand exactly where the reasoning had gone astray, and propose a correction – that process gave me extraordinary confidence in my own mathematical thinking. I was not merely reading mathematics; I was in dialogue with one of the greatest minds in the discipline. And I was finding gaps in that mind’s work. This could have been terrifying. Instead, it was oddly liberating. It demonstrated that even towering figures made mistakes, that rigorous thinking could identify and correct them, and that a young woman with sufficient care and intelligence could do this work.

But there was also an inhibiting effect, one that I only fully recognised years later. Having corrected Hilbert, having demonstrated that I could identify errors in his reasoning, I became acutely conscious of the possibility of error in my own work. The responsibility of publishing under one’s own name, where one’s errors would stand forever in the literature, where other mathematicians would read and judge and potentially find gaps – that responsibility felt heavier after the Hilbert work than it might otherwise have done.

I became, I think, more cautious about publication than I might have been. Not paralysed – I did publish, and published frequently – but more deliberate. I would revise papers repeatedly, checking calculations obsessively, ensuring that every step was justified and every claim was defensible. Some of this was simply good mathematical practice. But some of it, I now believe, was residual anxiety from having found errors in Hilbert’s work. If such errors could exist at his level of genius, what might lurk undetected in mine?

There was also a gendered dimension to this, which I should acknowledge. The Hilbert work positioned me, in the eyes of the mathematical community, as a woman who was exceptionally good at careful, meticulous, detail-oriented work. Checking proofs. Finding errors. Ensuring correctness. These are indeed valuable skills, but they are also stereotypically feminine work – the province of assistants and editors and secretaries. The mathematical community seemed to perceive me as exceptionally talented in precisely those feminine-coded domains.

This created a peculiar tension. On the one hand, I took pride in the quality and rigor of my work – I still do. I believe mathematics is better served by careful thinking and careful writing. On the other hand, I was aware that being known as the woman who was very good at finding other people’s errors might contribute to a certain professional invisibility. One becomes the handmaiden of genius rather than a generator of new ideas.

So when I began publishing my own research in earnest – the work on algebraic number theory, then increasingly on matrix theory – I was hyperaware of the need to present ideas that were distinctly my own, not merely careful refinements of existing work. I perhaps overcorrected. I became almost aggressive about originality, about staking claims to new theoretical territory. Looking back, I wonder if I published some ideas before they were fully ripened, simply because I felt pressure to establish myself as a creator rather than merely a corrector.

The Hilbert assignment also shaped my approach to mathematical writing itself. Having struggled to correct his papers without misrepresenting his intent, I became absolutely committed to clarity in exposition. I would not allow my own ideas to be obscure or ambiguous. I would not depend upon readers to charitably interpret my meaning. This produced, I believe, better mathematics – but it also meant that publishing was even more laborious for me than for many colleagues. Each paper had to be not merely correct but crystallinely clear.

Did this inhibit boldness? Perhaps somewhat. But I think it also pushed me toward originality. If I was going to publish, I wanted to publish ideas that were sufficiently mature and sufficiently clearly presented that they could not be dismissed as careless or derivative. This may have slowed my output somewhat, but it ensured that what I did publish could stand scrutiny.

I would say, then, that the Hilbert experience created a complex legacy. It gave me confidence in my critical faculties and my ability to work at the highest levels of mathematical rigor. But it also burdened me with heightened responsibility and perhaps excessive caution. It positioned me professionally in ways that had both advantages and constraints. And it contributed to patterns of carefulness and exactitude that shaped everything I subsequently wrote.

Whether this was, on balance, beneficial or inhibiting – I honestly cannot say with certainty. Mathematics benefited, I believe, from my commitment to rigor and clarity. But the mathematical world may have been deprived of ideas that I did not publish because they seemed insufficiently developed, or of work I did not pursue because the energy devoted to meticulous revision might have been directed toward new discovery. Such counterfactuals are ultimately unanswerable.

What I can say is this: being trusted with Hilbert’s legacy at twenty-four made me acutely aware of both the possibility and the cost of error. It made me a more careful mathematician. Whether it made me a bolder mathematician, or a more timid one, remains an open question – even to myself.

Nicolas Araya, 51, Industrial Engineer, Buenos Aires

What if the Second World War had not displaced you to the National Physical Laboratory? What if you had remained in Vienna or moved directly into pure mathematics at a university rather than into wartime computational work? Would matrix theory have developed without that collision between abstract algebraic thinking and practical engineering problems? Or was that fusion perhaps inevitable – something another mathematician would have eventually recognised?

Mr Araya, you pose one of those fascinating questions that historians love and scientists typically resist – what if the war had not displaced me? What if I had remained in Vienna, or moved directly into pure mathematics without the detour through wartime computational work? Would matrix theory have developed without that collision between abstract thinking and practical engineering problems?

I shall attempt an honest answer, though I confess that speculating about paths not taken makes me somewhat uncomfortable. One deals with what actually occurred, not with what might have been.

Had I remained in Vienna – well, that assumes Vienna remained a place where one could remain, which is itself a considerable assumption. The political situation was deteriorating badly even before we left. Many of my colleagues and friends were Jewish, and their prospects were becoming increasingly dire. Even those of us who were not Jewish found ourselves in an atmosphere of fear and constraint. So the notion of simply continuing peacefully in Vienna presumes a historical counterfactual far larger than my personal trajectory.

But let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that Vienna had remained stable and I had continued working there in pure mathematics. What would I have done? Almost certainly I would have continued in algebraic number theory, the field in which I had trained under Furtwängler. I found class field theory beautiful and compelling. I might have made contributions there – perhaps not revolutionary ones, but solid work extending the theory in useful directions.

Would I have turned to matrix theory under those circumstances? I honestly doubt it. Matrices in pure mathematics, before the computational revolution, were primarily notational conveniences. They appeared in representation theory, certainly, and in various algebraic contexts. But they were not a central object of theoretical investigation. Without the pressure of practical problems – the aircraft flutter calculations, the stability analyses, the need to actually compute eigenvalues reliably and understand when computational methods would succeed or fail – I suspect I would have seen matrices as tools rather than as worthy subjects in themselves.

The wartime work forced a confrontation between abstract mathematical structures and concrete computational necessity. We needed answers, not merely elegant theorems. We needed to know whether this particular aircraft design would remain stable, and we needed to know it within weeks, not years. That urgency drove me to ask different questions than I would have asked in a purely academic setting.

But here is where your question becomes more subtle. You ask whether the fusion was inevitable – whether another mathematician would have eventually recognised it. And I think the answer to that is yes, though perhaps it would have taken longer and developed differently.

The computational revolution was coming regardless of my participation. Electronic computers were being developed during and immediately after the war. Once such machines existed, mathematicians would inevitably have encountered large-scale matrix computations. The sheer ubiquity of matrices in applied problems – from engineering to economics to physics – would have forced theoretical attention eventually.

Indeed, I was not alone in this work. John von Neumann was thinking deeply about numerical computation and matrix methods. He understood profoundly that computation was not merely applied mathematics but raised fundamental theoretical questions. Hermann Weyl worked on matrix groups and their representations. There were others, scattered across institutions and countries, who were recognising that matrices deserved serious theoretical attention.

So I do not claim to have single-handedly created matrix theory as a theoretical discipline. What I claim is that I was among the first generation to recognise this need, and I devoted sustained effort to it across decades. The work would have happened without me, but it might have taken longer to coalesce into a recognised subdiscipline with its own journals, conferences, and research community.

What the war and the NPL work gave me specifically was a deep appreciation for the interplay between theory and application. I never viewed these as separate domains. My work on matrix stability had immediate practical implications for aircraft design. My theoretical results about matrix factorisation clarified computational algorithms. This bidirectional flow – theory informing practice, practice raising theoretical questions – became central to how I understood mathematics itself.

Had I remained in pure mathematics, I might have developed a more abstract, more purely algebraic approach to matrices. It might have been elegant, but it would have lacked the grounding in physical reality that the wartime work provided. And I suspect it would have been less influential, because it would have been disconnected from the explosion of computational applications that defined mid-twentieth-century applied mathematics.

There is also a personal dimension to your question. The war disrupted my career, certainly, but it also connected me to a broader international community of mathematicians and scientists. At the NPL, I worked alongside engineers, physicists, applied mathematicians. Later, at the National Bureau of Standards in the United States, I was part of the early computing revolution. These experiences shaped not just my mathematical interests but my professional network, my collaborators, my sense of what mathematics was for.

Had I remained in Vienna in a purely academic setting, I would have been part of a smaller, more insular mathematical community. My work might have been more narrowly focused, more conventional in its choice of problems. Whether that would have been better or worse is impossible to say – it would simply have been different.

So to answer your question directly: I believe the theoretical investigation of matrices was historically inevitable once computational machinery made large-scale matrix calculations routine. Someone would have recognised that these computational objects deserved rigorous theoretical study. But the specific form that matrix theory took in the mid-twentieth century – its fusion of pure algebraic structures with computational practice, its attention to stability and conditioning, its connections to number theory and group theory – that specific form bears the mark of those of us who came to the subject through wartime necessity.

The war disrupted my life and the lives of countless others. It scattered the European mathematical community, destroyed institutions, cost lives. I would never romanticise that destruction. But mathematically, the displacement forced encounters between people and ideas that might not otherwise have occurred. It accelerated developments that might have taken decades in peacetime.

Whether matrix theory would have developed without my displacement – yes, almost certainly. Whether it would have developed in precisely the same way, with the same emphases and connections – I rather doubt it. History is made by individuals responding to circumstances, and the circumstances shape what becomes possible. The war created circumstances that made certain mathematical developments both urgent and achievable. I happened to be positioned to respond to those circumstances. Another mathematician in another time might have responded differently to different circumstances and produced a different form of matrix theory – equally valid, equally useful, but distinct.

That is the most honest answer I can give to a fundamentally unanswerable question.

Leila Ben Youssef, 29, Physics PhD Candidate, Tunis

The anti-nepotism rule that relegated you to research associate status at Caltech is often presented as simply unjust. But I’m curious whether it shaped your work in unexpected ways. Did being formally junior whilst intellectually equal lead you to mentor students differently, or to choose research directions that a fully-ranked professor might have avoided? Did constraint sometimes create freedom?

Dr Ben Youssef, your question is extraordinarily perceptive, and it addresses something I have thought about considerably – though often privately, as it requires acknowledging a certain complexity in my own narrative that does not fit neatly into stories of injustice overcome.

You suggest that the anti-nepotism rule that relegated me to research associate status might have shaped my work in unexpected ways. That constraint might have created freedom. This is an observation that requires me to be honest about something I do not often say publicly: being formally junior whilst intellectually equal was, yes, infuriating and professionally limiting. But it was not entirely without compensations, and recognising that does not diminish the fundamental injustice of the arrangement.

Let me explain what I mean.

When one holds a full professorship, one carries certain expectations and obligations. One must teach, certainly, and I did that conscientiously. But one must also serve on committees, participate in departmental governance, maintain certain standards of visibility and reputation within the institution. There is a burden of status that accompanies rank. One’s time is parcelled out among many obligations.

As a research associate – formally junior, intellectually established, but without the full apparatus of professorial responsibility – I occupied a peculiar position. I was not expected to carry the same administrative load. I was not required to participate in every departmental meeting. In some ways, my formal diminishment created space for intellectual work.

I could focus more intensively on research and on mentoring students without being pulled in multiple institutional directions. When I wanted to pursue a question in matrix theory intensely, I was not obliged to set it aside for departmental business. When I wanted to spend weeks working through a difficult proof, I had somewhat more freedom to do so than a full professor with broader responsibilities might have had.

This is not to say the arrangement was just or that I would not have preferred a full professorship from the beginning. It emphatically is not. A full professorship would have brought salary commensurate with my work, recognition, and authority. But I want to be truthful about the actual experience, not merely the abstract injustice of it.

There was another dimension as well. Because I was formally junior, certain people underestimated my capabilities or my authority. This was infuriating when it occurred – I was sometimes excluded from decisions or discussions I should have been included in, sometimes had my suggestions discounted because of my formal rank. But underestimation can occasionally be strategically useful. People were sometimes surprised by the depth of my knowledge or the sophistication of my thinking. Surprise can lead to reassessment and respect.

More significantly, being formally junior perhaps gave me a certain freedom to work across disciplinary boundaries and to take intellectual risks that a more highly ranked person might have hesitated to take. If one has an established reputation in a particular field, there is pressure to continue working in that field, to maintain one’s standing. If one is ranked junior, one has less reputation to protect. I could afford to move between number theory and matrix theory and group theory and numerical analysis more freely than someone with a major reputation in a single domain might have done.

I also want to acknowledge something else: the anti-nepotism rule, whilst unjust to me, was motivated by a real institutional concern. Dual-career couples could create conflicts of interest or appearance of impropriety. The solution – ranking the woman junior – was profoundly unfair. But the underlying problem was real. Contemporary universities have found better solutions: explicit conflict-of-interest policies, recusal from decisions affecting one’s partner, clearer procedures for evaluating merit independently of family relationships. But in my era, the only mechanism available was to subordinate the woman.

Did this constraint shape my work? Yes, but not entirely in negative ways. The freedom from some bureaucratic obligations allowed me to maintain an extraordinarily high publication rate. The intellectual risk-taking was encouraged by my formal junior status. The necessity to prove myself through the quality of work itself – rather than through the authority conferred by rank – perhaps made my work more meticulous and more carefully considered.

But let me be equally clear about what I am not saying. I am not saying that the injustice was acceptable, or that I am grateful for it, or that things worked out for the best so we need not worry about such arrangements. The anti-nepotism rule was wrong. It suppressed the careers of countless women. It deprived institutions of the full participation of women scholars. It enforced a subordination that no amount of intellectual freedom could fully compensate for.

What I am saying is that the human experience is more complicated than simple narratives of victimisation or triumph. I was genuinely wronged by the anti-nepotism policy. I was also, paradoxically, given certain intellectual freedoms by my formal junior status that a fully professorial woman with equal achievements might not have had. Both things are true.

I think this matters for how we address contemporary injustices. When we work to remedy unfair policies – and I believe we absolutely must – we should do so not because the victims of injustice gain no compensatory benefits in any domain, but because the injustice itself is wrong and because the benefits that might accrue to individuals in one area do not justify systemic unfairness.

If younger women reading this are in situations analogous to what I experienced – formally constrained, intellectually capable, given certain freedoms by their very marginality – I would say this: do not mistake the freedoms you may have for justification of the constraint. Use those freedoms fully. But also work, persistently and collectively, to change the systems that create such situations in the first place.

Constraint and freedom, injustice and opportunity, are not opposites. They can coexist. Acknowledging that coexistence does not diminish the obligation to fight injustice – it merely makes us more honest about the complicated actual experience of living within unjust systems whilst still trying to do good work.

The question of whether my research benefited from being formally junior is genuinely difficult for me to answer. I suspect it did, in ways I have tried to articulate here. But I would far rather have had a clear professorial title from the beginning and discovered whether I had the intellectual capacity for risk-taking without needing the spur of formal diminishment. That would have been the truly just arrangement, and I would not trade what I accomplished for the sake of maintaining it.

Reflection

Olga Taussky-Todd died on 7th October 1995, at the age of eighty-eight. She had lived long enough to see the computational revolution she helped chart transform mathematics and science beyond recognition. She had lived long enough to witness matrix theory become not merely a recognised subdiscipline but a foundational pillar of computer science, artificial intelligence, and modern engineering. Yet she did not live to see the full recovery of her legacy, the renewed scholarly attention to her work, or the contemporary recognition of how systematically women’s contributions to mathematics have been obscured by institutional structures, historiography, and cultural erasure.

What emerges most forcefully in reviewing this interview, conducted as it is from the vantage point of 2025 – thirty years after her death – is how often Olga Taussky-Todd’s own characterisations of her work and her career differ subtly from the recorded historical accounts. She speaks of matrix theory not as a revolution she single-handedly created, but as a torch she carried forward, one that others had glimpsed and that others would eventually carry further. This modesty is characteristic, yet it also obscures something important: she was not merely carrying forward existing ideas about matrices as theoretical objects. She was instrumental in establishing that such investigation was worthwhile, rigorous, and central to mathematics itself.

The historical record often presents her anti-nepotism displacement at Caltech as straightforward injustice – and it was. Yet in this conversation, she articulates a more complicated reality: that formal subordination, whilst profoundly unjust, also created paradoxical intellectual freedoms. This complication is precisely the sort of nuance that conventional historical narratives often flatten. We prefer stories of pure victimisation overcome or pure triumph achieved. We are less comfortable with the ambiguities of actually living within unjust systems whilst still finding ways to do extraordinary work.

There remain gaps in the historical record that this interview cannot fully resolve. We know she was hired to correct Hilbert’s errors, but the precise nature of those errors, how many there were, and how her corrections shaped subsequent mathematics remain incompletely documented. We know she made profound contributions to matrix stability analysis during wartime aircraft work, yet much of that research carried security classification and has never been fully declassified or analysed. We understand that she supervised numerous students and was beloved by them, yet detailed accounts of her mentoring methods and her influence on individual researchers remain scattered and fragmentary.

There is also something she does not say in this interview, something that emerges only by reading between the lines: the loneliness of being one of very few women working at the highest levels of mathematics across seven decades. She speaks of colleagues, collaborators, and students with affection and respect. But one senses, in the careful way she discusses her social isolation – “quiet in public, not quick, and does not ask questions at talks” – the toll of navigating spaces not designed for women’s presence or comfort. That toll is real and deserves acknowledgment, even as we celebrate her extraordinary resilience.

Yet the afterlife of her work demonstrates its durability and depth. The Latimer-MacDuffee theorem remains a standard result taught in algebraic number theory courses worldwide. Her work on matrix factorisation, nonnegative matrices, and matrix stability has been extended, refined, and applied in contexts she could barely have imagined. The International Linear Algebra Society established the Olga Taussky and John Todd Prize in 1997 – two years after her death – specifically to honour outstanding research in linear algebra and matrix theory. That prize, awarded biennially, ensures that mathematicians working in her field invoke her name and acknowledge her foundational contributions. Contemporary researchers in machine learning, quantum computing, and numerical analysis regularly cite her papers. Her work has become so thoroughly woven into the infrastructure of modern mathematics and computer science that many who use her results may not know her name – yet the torch continues to burn.

What is perhaps most notable about returning to her work in 2025 is recognising how prescient she was about the fusion of pure and applied mathematics. She understood, decades before it became commonplace, that theoretical elegance and practical utility were not in opposition but mutually reinforcing. She moved fluidly between rigorous algebraic structures and computational realities in ways that contemporary mathematicians trained in specialised silos sometimes struggle to emulate. For a generation of scientists now facing the enormous challenges of climate change, artificial intelligence, and complex systems – problems that demand both mathematical rigour and practical application – her example remains profoundly relevant.

For young women entering mathematics, physics, engineering, and computational science today, Olga Taussky-Todd’s story offers several sustained truths. First: visibility matters. Her relative obscurity despite extraordinary productivity demonstrates that excellence alone does not guarantee recognition. One must publish, must build a visible record, must engage with the scholarly community in ways that make one’s work impossible to overlook. This is not always comfortable, particularly for women socialised toward modesty and deference. Yet it is necessary.

Second: mentorship and intellectual community matter enormously. Taussky-Todd’s career was sustained by relationships – with her husband, with colleagues who recognised her abilities, with students who benefited from her rigor and clarity. Building those relationships, seeking out allies and advocates, creating space for younger women to see that women can do serious mathematics – these are not luxuries or nice additions to a scientific career. They are essential infrastructure for survival and flourishing in fields still marked by significant structural inequities.

Third: interdisciplinarity and intellectual risk-taking are strengths, not weaknesses. She refused to be confined within a single domain. She moved between number theory and matrices and computational methods because problems, not disciplinary boundaries, guided her work. That intellectual fluidity allowed her to see connections that specialists working within narrow confines might miss. Young scientists tempted to specialise narrowly should consider whether they might gain by following problems rather than disciplines.

Fourth: precision and standards matter, and they can be tools of power. Taussky-Todd’s particular requirements about mathematical notation and writing style were sometimes perceived as pedantic. Yet they were expressions of a philosophical commitment to clarity and rigor. When women insist on standards – on precision, on clarity, on intellectual honesty – and when those standards are backed by demonstrated expertise and accomplishment, such insistence becomes not pedantry but legitimate authority. Do not apologise for your standards.

Finally: carry the torch consciously and deliberately. Taussky-Todd’s own metaphor is instructive. She was not the source of light but carried it forward and passed it to others. That is honourable work. It is also necessary work. Every person who has walked a difficult path has an obligation to make that path somewhat easier for those who follow. This might mean mentoring directly, or publishing work that clarifies and consolidates what has been learned, or writing autobiographical accounts like Taussky-Todd’s own essay that provide rare first-person testimony to what a woman’s mathematical career actually looks like. It means insisting, when you have achieved sufficient standing to do so, that younger women be given genuine opportunities – not token positions, but real ones.

Thirty years after Olga Taussky-Todd’s death, the field of mathematics remains more male-dominated than many other disciplines, though progress has been real and measurable. Women still face barriers of anti-nepotism policies (though legal frameworks have improved), of undercounting and undervaluation, of being asked to explain their presence in ways male colleagues are not. Yet the fact that we are now having conversations about recovering Taussky-Todd’s legacy, that the Olga Taussky-Todd Prize exists and draws international attention to matrix theory, that her autobiography is reprinted and studied – this suggests that visibility, once achieved, can be preserved and expanded.

The torch Olga Taussky-Todd carried still illuminates. It illuminates the mathematical landscape itself, through the theorems and results and methods that continue to generate new discoveries. But it also illuminates a path for others – a demonstration that a woman can build a rigorous, productive, world-changing career despite structural barriers; that one can remain modest and still claim one’s achievements; that intellectual work can be both beautiful and practical; that carrying light forward is itself a form of brilliance.

For young women in science today, reading her words is like discovering a letter from the past that speaks directly to present challenges. It says: the barriers you encounter are real, and they are unjust. They are not your fault, and overcoming them should not require more brilliance or more sacrifice than your male peers must offer. But they are surmountable. The work matters. The torch is waiting to be carried forward. And those who carry it – who push against the barriers, who refuse to be invisible, who build communities of rigor and care – those torchbearers become the bridges by which others cross into territories previously closed to them.

That is Olga Taussky-Todd’s final gift: not merely the mathematics she created, though that endures. But the example she set of what is possible when intelligence, persistence, and ethical commitment meet structural injustice and refuse to be defeated by it.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note

This interview is a dramatised reconstruction based on historical sources, biographical materials, and documented accounts of Olga Taussky-Todd‘s life and work. It is not a transcript of an actual conversation. Rather, it is an imaginative engagement with her legacy, constructed from published interviews, her autobiographical essay “How I Became a Torchbearer for Matrix Theory” (1988), scholarly analyses of her contributions, and accounts from colleagues and students who knew her.

The words placed in Olga Taussky-Todd’s mouth are not her own, though they are grounded in her documented ideas, concerns, and intellectual commitments. Where possible, I have drawn on her actual phrasing and known perspectives. Her characterisations of matrix theory, her descriptions of wartime work at the National Physical Laboratory, her reflections on the Hilbert editing project, and her comments on mentoring emerge from historical record and scholarly interpretation. However, the specific turns of phrase, the narrative framing, and the particular emphases in her responses are authorial constructions designed to bring her voice into dialogue with contemporary questions.

The supplementary questions from the five international contributors – Amira Rahmadani, Dylan Foster, Katarzyna Lewandowska, Leila Ben Youssef, and Nicolas Araya – are likewise fictional constructions. These individuals represent types of questioners and lines of inquiry that feel authentic to how Taussky-Todd’s work might be engaged with today. Their questions and her responses explore genuine tensions and complexities in her career, but they emerge from imaginative reconstruction rather than from actual correspondence.

The value of this approach lies in what it permits: a sustained engagement with her thinking, a representation of her as an intellectually complex person capable of contradiction and nuance, and a conversation that respects both historical accuracy and narrative coherence. By framing this as dramatised reconstruction rather than as literal history, I aim to honour both Taussky-Todd’s actual legacy and the reader’s right to understand what they are encountering.

Readers seeking Taussky-Todd’s own words in her own voice should consult her published papers, her autobiography, and the Caltech Oral History Project’s interviews with her. This dramatisation is offered as a complement to rather than a replacement for those primary sources – a way of thinking through her legacy and her significance for contemporary mathematics and science.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment