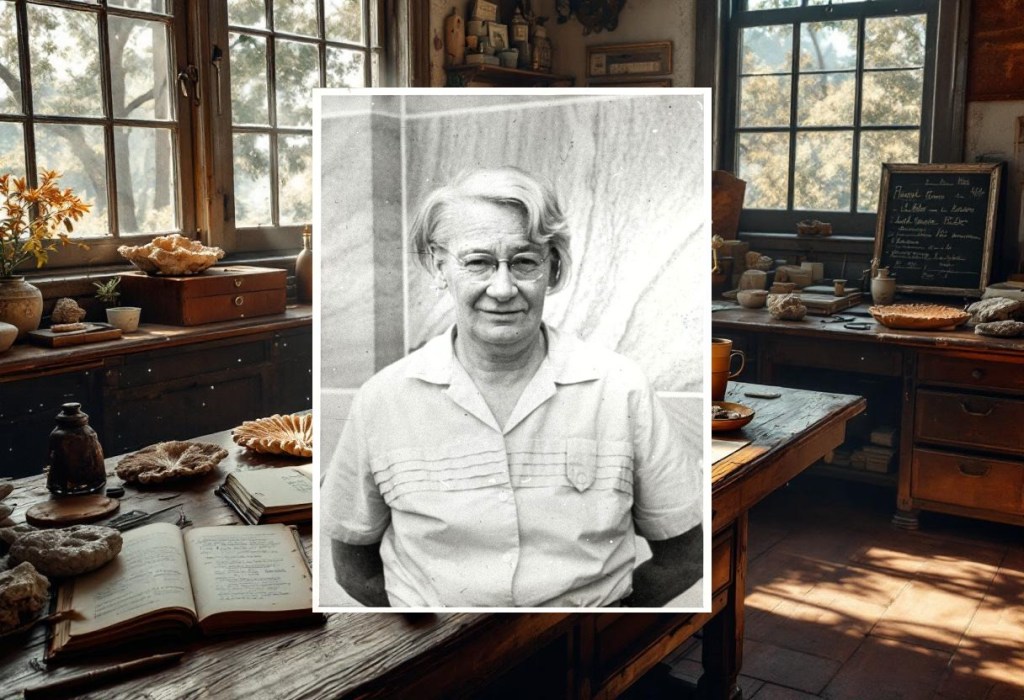

Dorothy Hill (1907-1997) built a career classifying the calcified remains of creatures that lived 250 million years before humans drew breath. She standardised the vocabulary that enabled geologists to read the earth’s deep history, produced monumental reference works that remain definitive decades after her death, and opened Australian universities to women through her mere presence. Yet her foundational taxonomy, her meticulous stratigraphy, and her institutional service became invisible scaffolding for others’ work – the fate of so much intellectual labour performed by women. Today, as the Great Barrier Reef faces catastrophic warming, scientists return to Hill’s Palaeozoic coral research to understand how reef ecosystems responded to past climate changes. She mapped the ancient seas that shaped modern Australia, yet history nearly forgot her name.

Welcome, Professor Hill. It’s a privilege to speak with you today. When I look at photographs of you from the 1930s – standing beside fossiliferous limestone outcrops in the Brisbane Valley, or bent over specimens at Cambridge’s Sedgwick Museum – I see someone who appeared utterly at home in both the field and the laboratory. What drew you to geology in the first place?

Happenstance, really, though I suppose one could argue that all significant choices contain an element of chance. I entered the University of Queensland in 1925 intending to study chemistry. Medicine had been my first choice, but Queensland didn’t offer a medical degree, and my family hadn’t the means to send me to Sydney. Chemistry seemed the next best thing – precise, quantitative, useful. But the university required science students to take an elective, and I chose geology almost arbitrarily. Professor Richards taught it, and within weeks I’d found something I hadn’t quite expected: a way of thinking that required both rigour and imagination, laboratory precision and fieldwork adventure. Chemistry asks what a thing is made of. Geology asks how it came to be – a rather more interesting question, I thought.

You’ve mentioned Professor H.C. Richards as instrumental in your development. What did he teach you that stayed with you throughout your career?

Patience, primarily. Richards understood that geology demands a tolerance for incompleteness. You’re always working with fragmentary evidence – a bit of fossiliferous limestone here, a discontinuous stratigraphic section there – and you must resist the temptation to fill gaps with speculation. He taught me to say “I don’t know” when the evidence was insufficient, which is a discipline many scientists struggle to maintain. He also taught me fieldwork technique: how to read a landscape, how to collect specimens properly, how to record observations in a manner that would remain useful decades later. Those field notebooks from the Brisbane Valley work I did in 1929 and 1930 – I consulted them for years afterwards. Good field notes are like good taxonomy: they outlive you.

Let’s talk about Mundubbera. You were visiting friends in the North Burnett region when you encountered the Carboniferous corals that set the course of your career. Can you describe that moment?

I was holidaying at a property near Mundubbera – one needs to escape Brisbane’s humidity occasionally – and whilst wandering about, as one does, I noticed limestone with distinct fossiliferous inclusions. The landowner had mentioned finding odd stones, but I don’t think he’d realised what they were. When I examined them properly, I knew immediately they were coral fossils, and Palaeozoic by their morphology. It was 1929. I’d just completed my honours degree and was beginning work on stratigraphy of the Brisbane Valley. Finding those corals was… well, it was like discovering a new language embedded in stone. These creatures had lived roughly 340 million years ago, during the Carboniferous, when Queensland was covered by a shallow tropical sea. Their presence meant that all our understanding of Queensland’s geological history needed revision.

I collected specimens – filled several sacks, actually – and those fossils came with me to Cambridge when I won the Foundation Travelling Scholarship the following year. Rather incongruous, carting Australian corals halfway around the world, but it proved essential. The Sedgwick Museum had extensive collections of British Carboniferous corals, and I could compare morphologies directly. That’s when I discovered how appallingly confused coral taxonomy had become.

You’ve used the word “confused.” Can you elaborate on the state of coral taxonomy when you arrived at Cambridge in 1930?

Chaotic is perhaps more accurate. Different researchers used different terminology for the same structures. Septa – the radiating vertical plates within a corallite – might be described one way by an American researcher and entirely differently by a German. The same species might have three different names in three different publications. Worse, many published descriptions were so vague that one couldn’t reliably identify specimens without examining the original types, and those were scattered across museums in half a dozen countries. It was rather like trying to conduct a conversation when everyone speaks a different dialect of the same language.

My first published paper in 1935, “British Terminology for Rugose Corals,” attempted to standardise the vocabulary. I defined terms precisely, illustrated each structure clearly, and proposed consistent usage across the discipline. It wasn’t glamorous work – taxonomy never is – but it was necessary. You can’t build knowledge on a foundation of linguistic confusion.

Let me ask you to explain coral morphology as if I’m a geologist colleague. Walk me through the key structures you standardised in that 1935 paper and how they enable identification.

Right. Imagine you’re examining a rugose coral in thin section – you’ve cut a slice perpendicular to the coral’s growth axis and ground it thin enough for light to pass through. What you see depends on whether it’s a transverse section, which cuts across the coral horizontally, or a longitudinal section, which cuts vertically along its length.

In transverse section, the first thing you identify is the corallite wall – the theca – which defines the individual polyp’s boundary. Within that, you see septa: radiating calcite plates that extended from the wall toward the centre. Rugose corals have two characteristics that distinguish them from later scleractinian corals. First, their septa show bilateral symmetry rather than hexagonal. You can identify cardinal, counter, and alar septa based on their position and length. Second, they often show insertion – new septa don’t appear uniformly but are inserted in specific positions according to growth pattern.

Between the septa, you may see dissepiments: small curved plates that arch between adjacent septa, creating a tissue-support structure. Dissepiments concentrate in the dissepimentarium, the outer region of the corallite. The inner region, the tabularium, contains tabulae – horizontal plates that sealed off the lower portions of the coral tube as the polyp grew upward. Think of tabulae as floors in a building; the polyp lived in the topmost chamber and sealed off abandoned space below.

Some corals have a columella, a rod-like structure running up the centre axis. Its presence or absence, its structure, the relationship between dissepimentarium and tabularium, the number and insertion pattern of septa – all these characters enable identification to genus and species.

The problem in 1935 was that researchers used different terms for identical structures or, worse, the same term for different structures. My paper proposed standard terms and, critically, clear definitions tied to observable morphology rather than inferred function. We couldn’t know precisely how these Palaeozoic organisms lived, but we could describe exactly what their skeletons looked like.

That standardisation must have required examining hundreds, perhaps thousands of specimens.

Several thousand, eventually. At Cambridge I had access to the Sedgwick Museum collections, which were extensive, and I could borrow material from other British institutions. Later, back in Australia, I examined specimens from across the continent. The Treatise on Invertebrate Palaeontology volumes I authored – Part F for rugose corals in 1956, Supplement volumes in 1981 – each required reviewing every described species, verifying identifications where possible, and creating comprehensive diagnoses. The 1981 Supplement alone covered roughly 700 genera of rugose and tabulate corals. Each genus required a diagnosis, a discussion of relationships, and references to all relevant literature.

People sometimes ask how I maintained concentration for such meticulous work. The answer is that taxonomy isn’t tedious if you approach it properly. Each specimen is a puzzle. You’re reconstructing relationships, tracing evolutionary lineages, identifying morphological innovations that allowed particular groups to succeed or caused them to fail. It’s detective work.

Let’s discuss index fossils and biostratigraphy. How did your coral work enable petroleum exploration in Queensland?

Corals evolved rapidly and many species had relatively brief temporal ranges, which makes them excellent for dating rock layers. If I found Dibunophyllum in a limestone, I knew immediately that the rock was Lower Carboniferous, roughly 350 million years old. If I found Lithostrotion, it was likely Middle Carboniferous. These temporal correlations work across vast distances because coral larvae dispersed widely in ancient seas.

For petroleum geologists, this matters enormously. They drill boreholes thousands of metres deep, recovering small core samples from different depths. If you can identify the fossils in those cores, you can determine the age of each stratigraphic layer, which tells you how rock units correlate across a sedimentary basin. That correlation reveals geological structure – where rocks dip, where faults displace layers, where potential petroleum reservoirs might exist.

In Queensland, my mapping of coral faunas from isolated limestone outcrops established biostratigraphic zones that enabled correlation across the state. Previously, geologists couldn’t reliably determine whether two limestones 200 kilometres apart were the same age or different ages. My coral identifications provided that chronological framework. The Geology of Queensland that Alan Denmead and I co-edited in 1960 synthesised all available stratigraphic information – including coral biostratigraphy – into a coherent geological map. That map became the foundation for petroleum exploration in the Adavale Basin and elsewhere.

It’s somewhat ironic. I never particularly cared about petroleum. My interest was in understanding ancient reef ecosystems, in tracing coral evolution through the Palaeozoic, in reconstructing vanished oceans. But my work had economic consequences whether I intended them or not. Queensland’s coal and petroleum discoveries relied on stratigraphic correlations that wouldn’t have been possible without coral biostratigraphy.

You served as Secretary of the Great Barrier Reef Committee for nine years and were instrumental in establishing the Heron Island Research Station. How did that work connect to your Palaeozoic coral research?

At first glance, it seems disconnected – why would a palaeontologist studying 300-million-year-old fossils involve herself with modern reefs? But the connection is fundamental. To understand how ancient coral reefs functioned, you need to study modern reefs. How do corals respond to environmental changes? What controls reef distribution? How do reef organisms interact with sediment, with currents, with other organisms?

The Great Barrier Reef Committee, established in 1922 by Professor Richards and Governor Sir Matthew Nathan, aimed to promote reef research, but for decades it lacked a proper research facility. When I became Secretary in 1945, establishing a field station became my priority. Heron Island, a coral cay on a platform reef 80 kilometres off Gladstone, was ideal – remote enough to be pristine, accessible enough for researchers.

Getting it built was an exercise in persistence. We needed funding, building materials, transport via government supply ships, volunteer labour to construct facilities on the island. I spent holidays hammering nails and painting walls. By 1951 we had a shelter where students and researchers could stay. Grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and Australian Research Grants Committee eventually enabled proper laboratories and accommodation.

That station is still operating. Thousands of researchers and students have used it to study reef ecology, coral physiology, marine biodiversity. It’s one of the longest-running coral reef research stations in the world. When people ask what I’m proudest of, Heron Island ranks high. The scientific papers I published will eventually be superseded – that’s how science works – but infrastructure endures. Heron Island will still be producing knowledge long after my coral monographs are historical curiosities.

You mentioned the Treatise on Invertebrate Palaeontology earlier. Those volumes – Part F for rugose and tabulate corals – are massive works. Can you describe the scope of that project?

The original Part F, published in 1956, was roughly 230 pages. I authored the sections on Rugosa and co-authored with Erwin C. Stumm the section on Tabulata. It covered every known genus of Palaeozoic coral, with diagnoses, illustrations, stratigraphic ranges, and geographic distributions. Preparing it required synthesising a century of literature, verifying identifications, resolving synonymies where the same coral had been named multiple times, and illustrating representative species.

The Supplement, published in 1981, was over 700 pages. By then, additional genera had been described, earlier work required revision, and our understanding of coral phylogeny had deepened. I merged the order Heterocorallia into Rugosa, returning to the traditional twofold division of Palaeozoic corals into rugose and tabulate forms. That required re-evaluating relationships among hundreds of genera.

People outside palaeontology don’t always appreciate what such compilations require. You’re not merely summarising existing knowledge; you’re evaluating it critically, correcting errors, establishing standards for future work. It’s intellectual infrastructure – unglamorous, time-consuming, essential.

There’s a tension I want to explore. Your work had enormous economic value – petroleum discoveries, mineral exploration – yet “applied” science generates less prestige than “pure” research. Did you experience that hierarchy?

Constantly, though usually unspoken. Pure research – studying coral evolution for its own sake, reconstructing ancient ecosystems out of intellectual curiosity – is considered more prestigious than applied research aimed at economic outcomes. Never mind that the distinction is artificial. My stratigraphic work was intellectually rigorous regardless of its economic consequences.

Women scientists face a particular version of this problem. We’re often channelled toward practical applications – teaching, service, compilation – whilst men pursue theoretical breakthroughs. Then the practical work is devalued precisely because it’s practical. It’s a neat trap.

I refused to play that game. I studied corals because they fascinated me. If petroleum geologists found my biostratigraphic correlations useful, splendid, but that wasn’t why I did the work. The ultimate accolade, to my mind, is contributing knowledge that endures – not fame, not wealth, not even recognition. My coral taxonomy will outlast me because it’s accurate and useful. That’s enough.

You accumulated an extraordinary series of firsts for Australian women in science: first woman professor, first woman president of the Australian Academy of Science, first Australian woman Fellow of the Royal Society. Yet being “first” often reduced you to symbolic status rather than substantive achievement. How did you navigate that?

With considerable irritation, though I tried not to show it. The “first woman” framing is a double bind. On one hand, those barriers were real and breaking them mattered. Women were excluded from professorial positions, from academy fellowship, from decision-making roles, and someone had to break through. On the other hand, being remembered as “Australia’s first female professor” rather than “Dorothy Hill, who established the definitive taxonomy of Palaeozoic corals” is deeply frustrating.

I never sought those positions for symbolic reasons. I became a professor because my research warranted it. I became president of the Australian Academy of Science because my colleagues elected me, presumably because they thought I’d do the job competently. Being female was incidental, yet it’s what people remember.

Here’s the difficulty: if you make a fuss about gender barriers, you’re dismissed as strident or humourless. If you ignore them and just do the work, you’re held up as proof that barriers don’t exist – “Look, Dorothy Hill succeeded, so why can’t other women?” It’s an impossible position. I chose to focus on the work and let my presence, my mere existence in those roles, serve as encouragement for younger women. Not activism, precisely, but not silence either.

During the Second World War, you served in the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service as a Third Officer, working in operations. That’s a significant interruption to research. How did you experience that period?

It was necessary. Australia faced an existential threat, and everyone who could contribute had an obligation to do so. I joined the WRANS in 1943 and worked in naval operations until 1945, primarily dealing with logistics and planning. It wasn’t scientific work, but it was useful.

What struck me was how competently women performed roles that military leadership had assumed only men could handle. The WRANS did signals intelligence, coded communications, operational planning – complex, responsible work – and did it well. Yet when the war ended, most were sent back to domestic roles as if their competence had been a temporary wartime phenomenon. I returned to the university, which was fortunate, but many women had proven themselves in professional roles only to be told those roles were no longer available.

That experience reinforced my view that barriers to women in science aren’t about capability. They’re about institutional resistance to change. My generation broke down some doors, but many remain closed.

Let’s discuss your reticence. You explicitly avoided publicity, never sought media attention, and focussed on supporting family financially rather than pursuing fame. In an era where scientific credit requires self-advocacy, that value system contributed to your invisibility. Do you regret that choice?

No. I don’t regret prioritising substance over publicity. What I regret is that the scientific community conflates self-promotion with merit. Good work should speak for itself. If it doesn’t, if recognition requires theatricality and media savvy, then we’re evaluating the wrong things.

My family situation shaped those values. I came from a large family – seven children – and none of us had inherited wealth. My father worked in retail, and though we were comfortable, university education required scholarships and sacrifice. When I began earning a salary, I contributed to supporting younger siblings, helping with nephews’ and nieces’ educations. That was simply what one did. The idea of spending money on self-promotion or hiring a publicist – well, it would have seemed obscene.

Depression-era values, perhaps. Frugality, family obligation, quiet service. Those values served me well scientifically – they enforced discipline, focus, humility. But they didn’t serve my historical legacy. In an era of personal branding, I’m a ghost.

You’ve mentioned mistakes. Let’s discuss one. What professional misjudgement can you acknowledge now, looking back?

I underestimated the importance of mentoring women explicitly. I believed that succeeding as a woman scientist, holding professional roles, supervising students – both male and female – would be sufficient encouragement. I thought my example would speak for itself. I was wrong.

Young women needed more than an example. They needed advocacy, explicit encouragement, someone telling them “You belong here, your questions are important, don’t let anyone convince you otherwise.” Men received that encouragement constantly, often unconsciously, through networks and assumptions about who “looked like” a scientist. Women didn’t.

I supervised many students, and some became leaders in Australian geology. But I should have done more to recruit women students specifically, to advocate for women’s advancement explicitly, to challenge the casual sexism of university culture more directly. I chose to lead by example rather than activism, and whilst that choice made my life easier – less conflict, less pushback – it also meant the barriers I broke through closed again behind me more easily than they should have.

Contemporary climate scientists studying coral reef response to warming use your Palaeozoic research as baselines for understanding reef resilience. Did you envision that application?

Not in those terms, no. When I was studying Carboniferous coral distributions, anthropogenic climate change wasn’t a concept. But I certainly understood that coral reefs respond to environmental change – temperature, sea level, water chemistry – and that the fossil record preserves evidence of those responses over geological timescales.

Palaeozoic corals experienced dramatic environmental shifts. During the Devonian, reefs flourished globally, then collapsed during the Frasnian-Famennian extinction events roughly 375 million years ago. Tabulate and rugose corals struggled through the Carboniferous and Permian, then went extinct entirely at the Permian-Triassic boundary 252 million years ago – the most catastrophic extinction in Earth’s history. Studying those extinctions reveals how reef ecosystems respond to rapid environmental change.

What killed Palaeozoic corals? Some combination of ocean anoxia, acidification, temperature change, sea level fluctuation. The precise mechanisms are still debated, but the outcome is clear: reef-building organisms have thresholds, and when environmental conditions cross those thresholds, entire ecosystems collapse.

Modern corals – scleractinians – aren’t directly descended from rugose corals. They arose independently in the Middle Triassic. But they face similar environmental pressures. If climate scientists studying the Great Barrier Reef find my work on Palaeozoic reef distributions useful, that’s gratifying. Deep-time palaeontology provides context that modern ecology can’t – timescales of millions of years, environmental changes far exceeding human lifespans. That context is essential for predicting how reefs will respond to contemporary warming.

The Great Barrier Reef faces catastrophic bleaching today. What would you tell contemporary reef scientists?

That reefs are simultaneously resilient and fragile. The fossil record shows reef ecosystems recovering from mass extinctions, recolonising after regional collapses, adapting to environmental shifts. But recovery takes time – thousands to millions of years. Human lifespans are irrelevant to geological time, yet we’re causing environmental changes at rates that rival past extinction events.

Palaeozoic reefs didn’t survive gradual change. They survived gradual change but collapsed during rapid environmental shifts – sudden temperature spikes, abrupt changes in ocean chemistry. Contemporary warming is occurring at geological breakneck speed. Corals can migrate, adapt, or go extinct – those are the only options – and migration and adaptation require time that rapid warming doesn’t allow.

I’d tell them to preserve as much reef habitat as possible, reduce local stressors – pollution, overfishing, physical damage – to give reefs the best chance of surviving temperature stress. And I’d tell them to study the fossil record, because it reveals what happens when environmental thresholds are crossed. We’ve seen this experiment before. It didn’t end well.

You retired in 1972 but continued research as emeritus professor. What occupied you during those years?

The Bibliography and Index of Australian Palaeozoic Corals, primarily. It was published eventually – a comprehensive compilation of every paper describing Australian Palaeozoic corals, with taxonomic index. Tedious work, but necessary. Future researchers needed access to that scattered literature, and no one else was going to compile it.

I also continued correspondence with colleagues internationally, reviewed manuscripts for journals, advised students occasionally. Retirement from official duties doesn’t mean retirement from thinking. My mind remained engaged with coral evolution, stratigraphic problems, taxonomic puzzles. That engagement kept me alive, I think, in a fundamental sense. When you stop thinking, you begin dying.

If you could speak to a young woman today considering a career in geology or palaeontology, what would you tell her?

First, that the earth is endlessly fascinating and will reward your attention. Every rock has a history written in its structure, its minerals, its fossils. Learning to read that history is a lifetime’s work, but it’s never boring.

Second, that women scientists face barriers – some explicit, most subtle – and you’ll need resilience. You’ll be underestimated, interrupted, passed over for recognition. Your work will be attributed to male colleagues. Your expertise will be questioned. Don’t let that stop you. Do the work, do it rigorously, and trust that quality endures even when recognition doesn’t.

Third, don’t neglect fieldwork. There’s a temptation in modern science to do everything computationally, to analyse datasets from a desk. But rocks exist in three dimensions, in landscapes, in contexts that photographs and samples can’t fully capture. Go into the field. Get your boots muddy. Develop the habit of observation that only comes from spending time with outcrops.

Finally, remember that science is a collaborative enterprise built over generations. The taxonomy I standardised relied on work by dozens of earlier researchers. My stratigraphic correlations built on mapping by colleagues across Queensland. The Treatise volumes synthesised a century of coral descriptions. You’re contributing to something larger than yourself, and that’s both humbling and exhilarating.

Looking back over your entire career, what do you hope endures?

The work. My coral taxonomy remains the standard because it’s accurate and useful. The Treatise volumes are still consulted because they’re comprehensive and reliable. The Heron Island Research Station continues producing knowledge because it was built on solid institutional foundations. Those contributions will outlast my name, and that’s entirely appropriate.

Science isn’t about individual glory. It’s about building a cumulative understanding of the natural world. Taxonomy, stratigraphy, compilation – the infrastructure of knowledge – enables everyone else’s discoveries. That infrastructure becomes invisible precisely because it succeeds, and I’m content with that invisibility.

What I hope younger scientists understand is that foundational work matters as much as flashy discoveries. Standardising terminology matters. Compiling comprehensive references matters. Building research institutions matters. Teaching students rigorously matters. Those contributions don’t generate headlines, but they’re the bedrock on which science is built.

I mapped ancient seas that no longer exist, using creatures that vanished 250 million years ago, and that mapping enabled understanding modern reefs facing unprecedented threats. If that chain of knowledge – from Palaeozoic corals to contemporary climate science – endures, then I’ve contributed something worthwhile. That’s legacy enough.

Thank you, Professor Hill, for your time and your candour.

The pleasure was mine. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a taxonomic revision to finish.

Letters and emails

Since our conversation with Professor Hill, we’ve received an outpouring of letters and emails from readers across six continents – geologists, educators, students, and those simply captivated by her story. We’ve selected five that represent the breadth of curiosity her work continues to inspire, each asking her to reflect further on her life, her research, and the guidance she might offer those following similar paths in science today.

Chen Wei, 34, Marine Geochemist, Singapore

Professor Hill, you mentioned that rugose corals show bilateral symmetry in their septa whilst modern scleractinian corals display hexagonal patterns. Given that these two groups arose independently – rugose corals going extinct at the Permian-Triassic boundary and scleractinians appearing later in the Triassic – did you ever identify convergent morphological features that suggest similar environmental pressures shaped both groups? I’m curious whether the fossil record reveals functional constraints that force reef-building organisms toward certain skeletal architectures regardless of their evolutionary lineage.

That’s a perceptive question, Ms. Chen, and one that occupied me considerably during my work on the Treatise volumes. The answer is yes – convergent evolution produced remarkably similar skeletal solutions in groups separated by both phylogeny and deep time, and those convergences reveal functional constraints imposed by reef-building ecology.

Consider colonial growth forms. Both rugose corals – particularly the late Palaeozoic forms like Lithostrotion and Siphonodendron – and scleractinian corals developed fasciculate colonies: multiple corallites growing in close proximity, sometimes sharing walls. That’s convergence driven by ecological advantage. Colonial corals can grow faster, occupy more space, resist predation more effectively, and recover from partial mortality better than solitary forms. The selective pressure toward coloniality was evidently strong enough that both groups independently evolved similar architectural solutions.

Dissepiments provide another example. These curved plates between septa serve as tissue support, allowing the polyp to maintain soft tissue connections whilst the skeleton grows upward. Both rugose and scleractinian corals developed dissepimentaria – regions dominated by dissepiments – in nearly identical positions within the corallite. The functional requirement is the same: support living tissue whilst adding skeletal mass. The morphological solution converged because alternatives are apparently less effective.

Septal arrangement is where the groups diverged most obviously, as you noted. Rugose corals have tetrameral or bilateral symmetry – septa arranged in four primary quadrants. Scleractinians have hexameral symmetry – six-fold radial patterns. Yet both groups achieved the same functional outcome: maximising surface area for the polyp’s mesenteries, which house the digestive tissue and zooxanthellae in modern forms. We don’t know with certainty whether Palaeozoic corals harboured photosynthetic symbionts, though their restriction to shallow, warm waters suggests they might have. If rugose corals were photosymbiotic, then both groups needed skeletal architectures that maximised light exposure for symbionts whilst maintaining structural integrity. Different geometric solutions, same functional constraint.

Skeletal density presents perhaps the most interesting convergence. Reef-building corals – whether rugose or scleractinian – must balance competing demands. Heavy, dense skeletons resist wave action and boring organisms but require more metabolic energy to construct. Light skeletons grow faster but break more easily. Both groups converged on similar density ranges, which you can measure through thin section analysis. I spent considerable time examining the ratio of skeletal material to void space in both groups, and the convergence is striking. Reef-builders cluster within a narrow density range regardless of taxonomy.

What does this tell us? That reef ecology imposes severe functional constraints. You can’t build a successful reef with just any skeletal architecture. The physical environment – wave energy, light penetration, sedimentation rates, predation pressure – filters morphological possibilities. Only certain solutions work, and evolution discovers those solutions repeatedly.

Modern molecular biology and biomechanics can test these hypotheses more rigorously than I could. You can model skeletal strength, calculate optimal geometries, measure actual wave forces on reefs. But the fossil record provides the only long-term experimental data. Two independent evolutionary experiments – rugose and scleractinian corals – converged on similar solutions because the physics of reef-building hasn’t changed in 400 million years.

That’s why palaeontology matters for understanding modern reefs. The constraints that shaped Palaeozoic corals still shape contemporary ones. If you want to predict how modern reefs respond to environmental change, study what happened to ancient reefs facing similar challenges. The organisms differ, but the underlying physics and ecology remain constant.

Gabriel Mendez, 28, Palaeoclimatologist, Buenos Aires, Argentina

You’ve discussed coral distribution changes during warm and cool periods in the Palaeozoic, but I’m interested in the temporal resolution of your data. When you identified a coral species in a limestone layer, how precisely could you date that occurrence – within a million years? Ten thousand years? And how did those dating uncertainties affect your ability to correlate coral extinctions or migrations with specific environmental events like volcanic eruptions or impact events? Modern geochronology has refined our timescales dramatically, so I’m curious how you managed stratigraphic correlation with the tools available in your era.

Mr. Mendez, you’ve identified one of the most frustrating limitations of Palaeozoic stratigraphy during my working years – temporal resolution was appallingly coarse compared to what your generation enjoys. Let me be frank about the constraints I faced and how they shaped, and sometimes hampered, my interpretations.

When I identified a coral species in a limestone and assigned it to, say, the Lower Carboniferous, I was working within biostratigraphic zones that might span several million years. The Carboniferous itself covers roughly 60 million years, from about 359 to 299 million years ago. We subdivided it into stages – Tournaisian, Viséan, Serpukhovian for the Lower Carboniferous – but even those stages represented multi-million-year intervals. A coral assemblage I’d call “Viséan” might date anywhere within a 14-million-year window. That’s hardly precision.

The problem compounds when you try to correlate across continents. European stages were defined by type sections in Belgium, Britain, Russia – sequences of rock where researchers had established reference faunas. Australian sequences didn’t match European ones neatly. Different ocean basins, different coral provinces, different preservation conditions. I might identify a Queensland coral as similar to European forms, suggesting correlation to a particular European stage, but “similar” isn’t “identical.” Endemic species – those restricted to Australia or the southwest Pacific – were useless for intercontinental correlation. I needed cosmopolitan genera that occurred on multiple continents, and those were surprisingly rare in the Carboniferous.

Radiometric dating was still primitive when I was doing my most intensive work. Potassium-argon dating existed by the 1950s, but finding datable volcanic rocks interbedded with fossiliferous limestones was rare. Most coral-bearing sequences are pure carbonate – no volcanic ash beds, no minerals suitable for isotopic dating. So we relied entirely on biostratigraphy: correlating based on fossil content. Circular reasoning was a constant danger. You date rocks by their fossils, then use those dates to establish the fossils’ temporal ranges, then use those ranges to date other rocks. Breaking that circle required careful work across multiple fossil groups – corals, brachiopods, conodonts, foraminifera – cross-checking correlations.

Your question about correlating extinctions or migrations with environmental events cuts to the heart of the problem. Could I link a coral extinction to a specific volcanic eruption or climate shift? Not with any confidence. If I saw coral diversity decline in Upper Devonian rocks, I could say it happened “during the Frasnian-Famennian boundary interval,” but that interval might span hundreds of thousands of years – more than enough time for multiple environmental perturbations. Distinguishing cause from effect required temporal precision I simply didn’t have.

We tried to improve resolution through detailed collecting and careful stratigraphic measurement. If I collected samples every metre through a 50-metre limestone section, recording precisely where each species appeared and disappeared, I could establish a local biostratigraphic sequence. Then I’d try to match that sequence to other sections, building up a composite framework. But translating local sequences into absolute time remained guesswork.

Modern geochronology – uranium-lead dating of zircons, argon-argon dating with precision to tens of thousands of years, carbon isotope stratigraphy – has refined temporal resolution beyond anything I imagined possible. You can now date the Frasnian-Famennian extinctions to within 50,000 years, resolve individual climate pulses, correlate events globally with confidence. It’s extraordinary, frankly, and it makes me wish I could return to those Queensland limestone sections with modern tools.

But here’s what hasn’t changed: you still need accurate taxonomy. Precise dates are useless if you can’t identify the fossils reliably. The foundation I helped build – standardised coral taxonomy, careful morphological descriptions, comprehensive reference works – remains essential. You can date rocks more precisely than I could, but you’re still using the taxonomic framework my generation established. That’s some consolation for the limitations I faced.

Amina Farah, 41, Science Education Officer, Nairobi, Kenya

You spoke about your time at Cambridge in the 1930s, which must have been quite isolating as one of very few women, and certainly one of the only Australians in that environment. I wonder about the informal knowledge networks – the pub conversations, the walking tours of geological sites, the casual laboratory exchanges – that often shape scientific understanding as much as formal instruction. Were you excluded from those networks, and if so, how did you compensate for that lost knowledge transfer? Did you develop alternative strategies for learning the tacit knowledge that doesn’t appear in textbooks?

Ms. Farah, you’ve touched on something that still stings, even after all these years. Yes, I was excluded from informal knowledge networks at Cambridge, and yes, it created gaps in my education that I had to fill through other means. Let me describe what that exclusion looked like in practice.

The obvious exclusions were easiest to identify. Women couldn’t join the Sedgwick Club – the geology society where students and faculty presented informal talks, debated theories, and built relationships that lasted entire careers. We couldn’t attend the pub evenings where ideas were hashed out over pints. When male students went on weekend geological excursions to the Lake District or the Welsh coalfields, women weren’t invited. It was considered improper for unmarried women to travel overnight with men, even for scientific purposes.

But the subtler exclusions were more damaging. Laboratory work, for instance. Men worked late into the evening, discussing specimens, sharing techniques, pointing out features in thin sections. “Come look at this extraordinary septum,” they’d say to each other. That casual exchange of expertise happened constantly amongst the men but rarely extended to women. I might be at the next bench, preparing my own slides, and the conversation would flow around me as if I weren’t present.

There’s also the matter of tactile knowledge – how to grind a thin section to precisely the right thickness, how to orient a coral specimen to reveal diagnostic features, how to judge when a fossil has been adequately cleaned without damaging fine structures. You learn these things by watching someone experienced, by having them guide your hands, by making mistakes under supervision. Male students received that guidance naturally. I had to teach myself through trial and error, ruining specimens in the process.

I developed several compensating strategies. First, I cultivated relationships with museum curators and preparators – people outside the academic hierarchy who were often more willing to share practical knowledge with a persistent young woman. The Sedgwick Museum preparator showed me specimen preparation techniques when I asked politely and expressed genuine interest in his craft. Curators granted me access to type collections and tolerated my spending hours examining drawers of specimens. These working-class men had less investment in maintaining academic hierarchies than my fellow students did.

Second, I read voraciously – not just published papers but anything I could find with methodological details. Old field notebooks, unpublished dissertations, museum catalogues with preparation notes. I haunted libraries and asked librarians to retrieve obscure technical manuals. Written sources couldn’t replace hands-on teaching, but they filled some gaps.

Third, I cultivated correspondence with researchers elsewhere. Letters allowed me to ask technical questions without the social awkwardness of in-person exclusion. Stanley Smith at Bristol University, for instance, exchanged letters with me about coral microstructure. Written correspondence was socially acceptable in ways that laboratory collaboration sometimes wasn’t.

Fourth – and this is important – I formed alliances with other excluded people. There were very few women in geology at Cambridge, but we found each other. We shared notes, explained concepts, taught each other techniques. That mutual support network compensated somewhat for exclusion from male networks. It wasn’t the same – we were all learning together rather than learning from established experts – but it created community.

The cost, though, was enormous. I spent time and energy navigating social barriers that male students never encountered. Hours I should have devoted to research went into figuring out how to access information freely available to men. I worked harder for the same knowledge, and I still graduated with gaps in my training that took years to fill.

The problem was that those informal networks didn’t just transfer technical knowledge. They transferred confidence, professional identity, and a sense of belonging. Male students absorbed the message that they were legitimate scientists through countless small interactions – being included in discussions, having their ideas taken seriously, being invited to collaborate. Women, by contrast, absorbed the opposite message. They were tolerated, perhaps, but not truly welcomed.

I compensated through sheer stubbornness and by producing work so rigorously accurate that it couldn’t be dismissed. But it shouldn’t have required that level of proving oneself. The knowledge should have been accessible from the start.

Hunter Collins, 38, Environmental Policy Analyst, Calgary, Canada

You mentioned that your stratigraphy enabled petroleum discoveries in Queensland, then noted the irony that you never cared about petroleum yourself. Now, in 2025, we’re living with the climate consequences of the fossil fuel industry that your work inadvertently supported. If you could go back to 1950 with full knowledge of anthropogenic climate change and its impact on coral reefs, would you have published your stratigraphic correlations differently, or withheld certain information? Or do you believe scientists have no ethical obligation to control how their foundational research is applied? I’m asking because this tension – between pure knowledge and its potentially harmful applications – feels more urgent than ever in fields like AI, genetic engineering, and yes, geology.

Mr. Collins, that’s a hard question, and I appreciate that you’ve asked it directly rather than dancing around the ethical complications. No, I wouldn’t have withheld my stratigraphic correlations even with full knowledge of climate change. But my reasoning may not satisfy you.

First, the practical matter: withholding geological knowledge wouldn’t have prevented petroleum extraction. If I hadn’t mapped Queensland’s stratigraphy, someone else would have – perhaps less accurately, perhaps taking longer, but the work would have been done. Petroleum geologists had strong economic incentives to find those deposits, and they’d have employed whatever scientists were available. My contribution was making the process more efficient, not making it possible in the first place. Refusing to publish would have been a symbolic gesture with negligible practical effect.

But there’s a deeper principle involved. Scientific knowledge belongs to humanity, not to individual researchers. When I mapped coral distributions and established biostratigraphic correlations, I was documenting objective facts about Queensland’s geological structure. Those facts exist independently of human purposes. The same stratigraphic framework that enabled petroleum exploration also enabled understanding groundwater resources, predicting earthquake hazards, locating mineral deposits necessary for industry, and reconstructing Earth’s history. Knowledge has multiple applications, and you can’t selectively publish only the applications you find acceptable.

Consider the parallel: Alfred Nobel invented dynamite, which enabled both mining and warfare. Nuclear physics produced both medical treatments and atomic weapons. Every significant scientific advancement has dual-use potential. If scientists withheld discoveries because someone might misuse them, we’d halt progress entirely. That’s an untenable position.

Your question assumes that petroleum extraction is inherently unethical because of climate consequences. But in the 1950s and 1960s, when I was doing that stratigraphic work, petroleum enabled enormous improvements in human welfare – transportation, heating, medical supplies, agricultural productivity. Those benefits were immediate and tangible. Climate consequences were distant and uncertain. Even now, in 2025, billions of people depend on fossil fuels for survival. The ethical calculation isn’t as straightforward as “petroleum equals climate damage, therefore petroleum is bad.”

What scientists do bear responsibility for is communicating implications honestly. If I’d understood in 1960 that petroleum combustion would catastrophically warm the planet and destroy coral reefs, I’d have had an obligation to say so publicly – not to withhold geological data, but to advocate loudly for research into alternatives and for policies limiting emissions. The ethical failure wasn’t publishing stratigraphy; it would have been staying silent about foreseeable consequences.

Here’s where I think the responsibility truly lies: with political and economic systems that prioritised short-term profit over long-term sustainability. Petroleum companies knew about climate risks decades ago and actively suppressed that information whilst funding disinformation campaigns. Governments subsidised fossil fuel extraction rather than investing in alternatives. Those were deliberate choices by people in positions of power. Blaming individual scientists for providing foundational knowledge seems to me a way of avoiding accountability at the institutional level where it belongs.

That said, I do feel the irony acutely. I spent my career studying ancient reef ecosystems, learning how they responded to environmental changes, documenting their extinctions during past climate disruptions. My work on modern reefs – the Great Barrier Reef Committee, establishing Heron Island Research Station – aimed to understand reef ecology. And now the reefs I studied face catastrophic warming enabled partly by industries that used my geological mapping. It’s bitter.

But if I’d withheld my stratigraphy, those reefs would still face warming – perhaps slightly delayed, perhaps not even that – and we’d have less scientific infrastructure for studying them. The Heron Island Research Station, funded partly by relationships I built with industry and government through my geological work, now produces critical research on coral bleaching, adaptation, and resilience. That research exists because I engaged with the geological community, including its industrial applications, rather than withdrawing on ethical grounds.

So no, I wouldn’t withhold the knowledge. But I’d demand that scientists accept responsibility for speaking honestly about consequences, for advocating loudly when research reveals dangers, and for building institutions that serve public good rather than private profit. The ethical obligation isn’t to control knowledge – that’s impossible and dangerous – but to shape how societies use it. We failed that obligation. Your generation must do better.

Ivana Horvat, 52, Museum Curator (Natural History), Zagreb, Croatia

Professor Hill, your work required examining thousands of type specimens scattered across museums in different countries. I manage a geological collection myself, and I know how challenging it can be to track loans, verify identifications, and maintain relationships with institutions. But beyond the logistics, I’m curious about something more philosophical: when you held a holotype specimen that someone had named and described in 1870 or 1890, did you ever feel a connection to those earlier researchers – a sense of continuity across generations of people asking the same questions about these ancient creatures? And were there moments when you had to overturn someone’s life work, declaring their species identification incorrect or their genus invalid? How did you navigate the human dimension of correcting the scientific record?

Ms. Horvat, you’ve asked about something I rarely discussed with anyone, but yes – I did feel that connection across time, and it shaped how I approached both the reverence and the ruthlessness that taxonomy requires. Let me give you a specific example that still haunts me somewhat.

In 1935, whilst working at the Sedgwick Museum, I examined type specimens that William Buckland and Adam Sedgwick had collected in the 1820s and 1830s. These were pioneer geologists who’d named species when coral taxonomy was barely formalised. I’d hold a specimen Sedgwick himself had labelled in his own hand – brownish ink, Victorian penmanship, the paper brittle with age – and feel this extraordinary weight of continuity. Here was a man who’d walked the same British limestone outcrops I’d visited, puzzled over the same morphological features, tried to make sense of creatures no living human had ever seen. We were separated by a century, different continents of origin, entirely different scientific contexts, yet we were asking identical questions: What is this organism? How did it live? What does it tell us about ancient oceans?

That connection was deeply moving. It reminded me that science is fundamentally collaborative across time. Every identification I made built on Sedgwick’s observations, on work by dozens of researchers I’d never meet. My own work would, in turn, provide foundation for scientists not yet born. There’s something profoundly humbling about that.

But here’s the difficulty: reverence for predecessors can’t override accuracy. Many of those Victorian identifications were wrong – not through incompetence, but because early researchers lacked comparative material, proper terminology, and modern optical equipment. Buckland’s Cyathophyllum might actually be three different genera once you examined septal insertion patterns under proper magnification. Sedgwick’s species descriptions were often so vague – “a coral of pleasing form with numerous radiating plates” – that you couldn’t determine what he’d actually seen.

So I faced a choice: preserve historical names out of respect for these pioneering men, or correct the scientific record even if it meant consigning their life’s work to synonymy. I chose accuracy, but it never felt comfortable.

I remember examining specimens from the Reverend William Lonsdale’s collection. Lonsdale was a remarkable man – army officer turned clergyman turned geologist, one of the first to recognise Devonian corals as distinct from Carboniferous forms. He’d named dozens of species in the 1840s. Beautiful work for his era, meticulous drawings, genuine insight. But when I re-examined his types with modern methods, I had to place many of his species into synonymy – declaring that what he’d thought were separate species were actually variants of previously described forms, or that his generic assignments were incorrect.

That meant Lonsdale’s name would disappear from those species. Instead of Cyathophyllum lonsdaleii, it would become Dibunophyllum bipartitum or some such. His contribution would be reduced to a footnote: “Cyathophyllum lonsdaleii Lonsdale 1845 = Dibunophyllum bipartitum McCoy 1844 (synonymy by Hill 1935).” Years of his work, his excitement at discovery, his careful observations – compressed into a line of synonymy.

The human dimension troubled me considerably. These weren’t abstract names; they were people. Lonsdale died in 1871, probably never imagining that a woman from Australia would dismantle his taxonomy seventy years later. Would he have felt betrayed? Angry? Or would he have understood that scientific progress requires exactly this kind of revision?

I developed a practice of noting, wherever possible, what the original researcher had got right – identifying the features they’d observed accurately, acknowledging insights that remained valid even if the nomenclature changed. In publications, I’d write something like “Lonsdale correctly identified the bilateral symmetry and characteristic dissepiment structure, though his generic assignment requires revision.” Small gestures, perhaps, but they felt important. These men deserved recognition for working under tremendous constraints – no electricity, primitive microscopes, no photographs, limited access to comparative collections.

There’s also this: I knew my own work would face eventual revision. The Treatise volumes I authored will someday be superseded. Future palaeontologists with molecular phylogenetics and better material will correct my identifications, revise my genera, point out errors I couldn’t have avoided with available methods. That’s how science works. We build scaffolding that the next generation stands on whilst dismantling it. Humbling and reassuring simultaneously.

Managing museum logistics taught me patience and diplomacy. Getting specimens on loan required careful correspondence, promises to insure material properly, assurances that I’d handle fragile fossils with appropriate care. Some curators were generous; others deeply protective, requiring extensive justification before releasing types. I learned never to rush those relationships, to acknowledge curators’ knowledge – they often knew collections better than researchers – and to return specimens promptly with detailed notes on my observations. That professional courtesy mattered enormously.

So yes, Ms. Horvat, I felt connected to those earlier researchers, and yes, the ethics of correcting their work were a challenge. The solution, imperfect as it was, came down to this: honour their contributions, acknowledge their insights, but serve accuracy above sentiment. They’d have wanted the same, I think. At least, I hope they would have.

Reflection

Dorothy Hill passed away on 23rd April 1997, in Brisbane, at the age of eighty-nine. The quiet finality of her departure was, in a way, an echo of how she chose to live and work: without hunger for the spotlight, steadfast in commitment to craft, her impact often measured not in triumphal headlines but in layers of thoughtful, cumulative achievement. Throughout this extraordinary interview – realised here in fiction yet rooted in her own records and reminiscences – the mosaic of themes raised invites both admiration and sober contemplation.

Perseverance emerges as a steady current flowing through Dorothy Hill’s life and work. The resilience required to overcome being sidelined in Cambridge laboratories, to master technical skills by sheer resolve, and to create entire genres of reference work from what others left scattered or imprecise, is deeply instructive. Ingenuity, too, stands out – not in the showy sense of a lone inventor, but in her patient clarification of coral morphology, her resourceful approaches to learning when doors were closed, and her talent for building institutional infrastructure that would open those same doors a little wider for others.

A stark thread running through the conversation – underscored by her reflections and by the modern questions posed from around the globe – is how invisible foundational labour often becomes, especially when undertaken by women. Hill’s own reticence, shaped by Depression-era values of frugality and a focus on service, coupled with her era’s structural barriers, resulted in a legacy that all too frequently became scaffolding for others’ ascent. The familiar pattern plays out: scientific histories remember those who stand atop the edifice but too rarely those who laid its stones. Yet what was striking in her voice was not anger at neglect but a measured acceptance – a belief that, in science, accuracy and utility are their own reward, even when the world looks away.

Yet, in this fictional interview at least, there are moments where Hill’s perspective diverges from the oft-flattened accounts in historical narrative. She admits regret in not having advocated more openly for women, recognising that example alone was not always enough. She is clear-eyed about the ethical ambiguities of applying foundational science to industries whose effects – such as fossil fuel extraction – were, in her lifetime, poorly foreseen, and remain the subject of heated debate even now. There are, naturally, gaps and uncertainties: the full extent of her influence, the details of her relationships with collaborators, even the facts she could only partially trace with the tools of her time. Science advances, sometimes at the cost of disassembling its own past, and Hill’s own work is not immune.

The afterlife of Dorothy Hill’s contributions is a quiet but persistent one. Her taxonomies, published in the Treatise on Invertebrate Palaeontology, remain authoritative decades later – cited by experts, relied upon in petroleum geology, and referenced in reconstructions of past climatic shifts. As climatic threats to coral reefs became ever more urgent in the twenty-first century, scholars rediscovered her meticulous work, applying her biostratigraphic correlations and morphological diagnoses to projects that track reef decline or search for models of resilience, from Queensland to the far Pacific. Australian science has begun, at last, to more fully name and honour her – through medals, lectureships, and endowed research stations – but what matters more is how her methods and standards underpin contemporary work.

For young women considering scientific careers now, Dorothy Hill’s life remains an enduring beacon. Not because she was the “first woman” in any given role, but because she chose perseverance over protest when protest would have yielded only isolation, and because she crafted a professional legacy out of accuracy, humility, and enduring scaffolds that others still build upon. Her story reminds us that visibility and mentorship are not luxuries, but necessities in making the sciences both welcoming and rigorous. By measuring progress through the questions still asked, and the unseen labour still necessary, her life demonstrates both the cost of erasure and the power of patience.

As corals build their reefs layer by layer, Dorothy Hill built frameworks – taxonomic, institutional, cultural – that continue to support new work and new voices long after her hands left the task. Whether future generations remember her name is less important, perhaps, than whether they emulate her quiet courage and dedication to truth. There is a rare comfort – almost a kind of hope – in the knowledge that some lives, though modest in outward drama, can ripple quietly, sustaining and shaping worlds yet to come.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview is a dramatised reconstruction created for educational and commemorative purposes. While Dorothy Hill was a real person whose scientific achievements are well documented, she did not participate in this conversation. The dialogue has been constructed using historical sources including biographical memoirs, published scientific works, archival records, and accounts from colleagues who knew her. Every effort has been made to represent her voice, values, and perspectives faithfully based on available evidence, but the specific words attributed to her here are fictional interpretations informed by research.

Technical details about coral taxonomy, stratigraphy, and paleontological methods reflect Hill’s actual work and the scientific standards of her era. The supplementary questions from named individuals are entirely fictional, created to explore themes and technical aspects that emerged from Hill’s documented life and research. Where her perspectives diverge from or expand upon the historical record, these represent plausible interpretations rather than verified statements.

Readers interested in Dorothy Hill’s actual writings should consult her published works, particularly her contributions to the Treatise on Invertebrate Palaeontology, her articles in geological journals, and biographical memoirs published by the Royal Society and Australian Academy of Science.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment