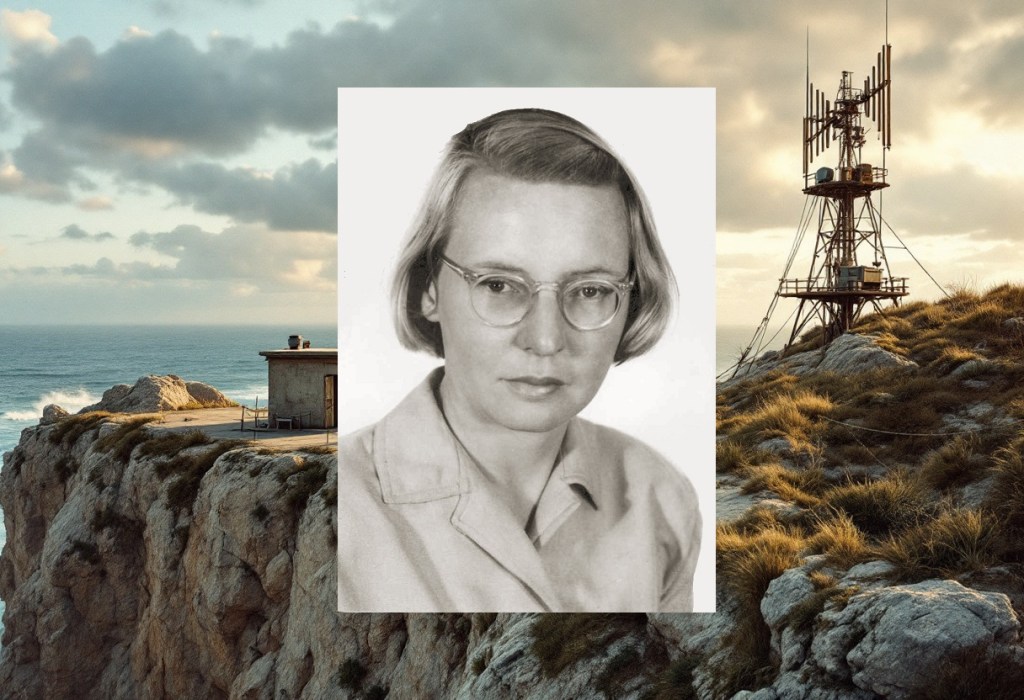

Ruby Payne-Scott (1912–1981) was a brilliant Australian physicist who pioneered radio astronomy whilst secretly fighting institutional discrimination that ultimately ended her research career. She developed radar technology during World War II, then used this expertise to become one of the world’s first radio astronomers, discovering solar radio bursts and pioneering interferometry techniques that remain fundamental to modern radio astronomy. Her forced resignation due to Australia’s marriage bar in 1951 represents one of science’s most significant losses to systemic gender discrimination.

Welcome, Ruby. It’s remarkable to be speaking with someone who literally helped create the field of radio astronomy. Your work in the 1940s opened up an entirely new window on the universe. How does it feel to know that techniques you developed are still being used today in facilities like the Square Kilometre Array?

Well, that’s rather gratifying, isn’t it? Though I must say, when Joe Pawsey and I first pointed those Yagi aerials at the sun from Dover Heights in ’46, we weren’t thinking about grand cosmic visions. We were trying to sort out where these peculiar radio signals were coming from – whether they originated from the sun itself or were some sort of atmospheric interference. The fact that our sea-cliff interferometer has grown into these enormous international arrays… it’s quite beyond what any of us imagined.

Your path to physics was unusual for women of your generation. Can you tell us about those early influences?

Mother was the key, really. She’d been a teacher before marriage – naturally had to give that up – but she was determined her children shouldn’t waste their minds. Home schooling until I was eleven meant I could move at my own pace, particularly in mathematics. When I finally got to Sydney Girls High, I was already ahead in maths and absolutely mad about it. Physics came later, at university. There was something tremendously appealing about the precision of it all, the way you could design an experiment and tease truth from nature.

The University of Sydney was… well, let’s say it wasn’t crawling with women in the physics department. I was the third woman to complete a physics degree there. Professor Love in the cancer research laboratory was decent enough – let me work on proper research, not just washing glassware. We investigated whether Earth’s magnetic field affected biological processes. Sounds rather quaint now, but it was serious work then.

Your wartime radar research was classified for decades. What was that work really like?

Fascinating and utterly essential. The radar systems that worked brilliantly in temperate Europe were hopeless in the tropical Pacific – the humidity played havoc with the electronics. I developed noise measurement techniques to assess receiver sensitivity under these conditions. It wasn’t glamorous work, but it meant our boys could spot Japanese aircraft at greater distances, even in monsoon weather.

The irony is that the marriage bar nearly prevented me from contributing to the war effort at all. In 1944, I married Bill Hall – secretly, of course. My colleagues knew, mind you. Pawsey and the others helped me maintain the fiction. I wore my wedding ring on a chain round my neck. Rather medieval, when you think about it.

Let’s talk about that pivotal moment on Australia Day, 1946. You conducted what many consider the first radio interferometry observation in astronomy. Walk us through that morning.

Right, well, I’d been reading Michelson’s work on stellar interferometry, and it struck me that our coastal radar stations presented a perfect opportunity to apply similar principles. The Dover Heights site had this lovely 85-metre cliff face – essentially giving us a 170-metre baseline when you counted the reflection off the sea surface.

I woke before dawn on the 26th – Australia Day, as it happened – and set up the equipment to track the sun as it rose. The Yagi aerial picked up both direct solar radiation and the signal reflected from the ocean. As the sun climbed, the interference pattern shifted in a most beautiful, predictable way. The maths were rather involved – I spent weeks with my slide rule working out the Fourier transforms by hand – but the result was extraordinary. We’d created the first radio image of the sun, and it showed the radio emission was coming from precisely where the optical sunspots were located.

That’s remarkable technical work. Can you give us the expert-level detail on how this interferometry actually functioned?

Certainly. The principle relies on what we now call the van Cittert-Zernike theorem, though we were working it out from first principles then. When you have two receivers separated by a baseline distance B, the correlation between their signals is the Fourier transform of the source brightness distribution.

In our sea-cliff arrangement, the direct signal arrived with phase φ, whilst the reflected signal had phase φ + 2πBsinθ/λ, where θ is the solar elevation angle and λ the wavelength. As the sun rose, θ changed continuously, creating interference fringes with a period determined by λ/Bsinθ.

The beauty of the 200-megahertz frequency we used was that it provided sufficient resolution – about 3 arcminutes – to distinguish features on the solar disc. The correlation function we measured was proportional to the visibility function, and by tracking this as the baseline projection changed with solar elevation, we could reconstruct the brightness distribution.

The technical challenges were considerable. Receiver stability was crucial – any phase drift would corrupt the interferometric signal. We used crystal oscillators and carefully matched the electrical path lengths in both receivers. The dynamic range was also limiting – solar bursts could be 10,000 times brighter than the quiet sun background.

What advantages did this technique offer over existing methods?

The resolution improvement was dramatic. Single-dish observations at 200 MHz gave us perhaps 30-arcminute resolution – hopeless for solar studies. The interferometer achieved 3-arcminute resolution with an 85-metre cliff, but more importantly, it demonstrated that resolution scales directly with baseline length. We immediately realised we could build larger arrays for even finer detail.

There were also sensitivity advantages. The interferometer naturally suppressed uniform background emission whilst enhancing compact sources. This made it ideal for studying solar active regions against the quiet sun background.

The technique was also remarkably robust. Unlike optical interferometry, radio interferometry wasn’t limited by atmospheric seeing. We could operate in any weather, day or night.

Your work revealed different types of solar radio bursts. What did you discover?

We identified three distinct burst types – I discovered Types I and III personally, and contributed to the Type II work. Each had characteristic frequency structures and durations.

Type I bursts were brief, intense pulses lasting seconds, occurring in chains or storms. Type III bursts were the real revelation – they showed a distinctive frequency drift, starting at high frequencies and sweeping down to lower frequencies over several seconds. This drift pattern suggested electrons spiralling outward through the solar corona at velocities of roughly one-third the speed of light.

The Type III observations were particularly elegant. By measuring the time delays between the burst arrivals at different frequencies, we could map the density structure of the solar corona. Higher frequencies originated deeper in the corona, where plasma densities were greater.

You also developed the swept-lobe interferometer at Potts Hill. How did this advance the field?

Ah, that was a lovely bit of engineering. Alec Little and I built it in 1949 – the world’s first instrument capable of following solar radio sources in real time as they moved across the sky.

The concept was to oscillate one aerial rapidly – dozens of sweeps per second – creating a moving interference pattern. When combined with a stationary aerial, this produced a “swept lobe” that could track moving radio sources. We could literally watch solar disturbances propagate outward from active regions.

The temporal resolution was extraordinary for its time – we could follow burst sources moving at several hundred kilometres per second across the solar surface. This revealed that many solar radio events weren’t stationary explosions but moving phenomena, probably related to shock waves or particle beams propagating through the corona.

Let’s address the elephant in the room – the marriage bar that ended your career. How did you navigate those restrictions?

It was institutionalised discrimination, pure and simple. The Public Service Act required women to resign upon marriage, based on the absurd assumption that wives couldn’t manage both domestic and professional duties. Men, apparently, were immune to such conflicting loyalties.

The hypocrisy was staggering. During wartime, when we desperately needed skilled personnel, my marriage status was conveniently overlooked. But once the crisis passed, the bureaucrats rediscovered their principles. I fought it vigorously – wrote letters pointing out the contradiction between the Act’s actual wording and the regulations being enforced.

What was your argument exactly?

The Act itself made no mention of married women. The marriage bar was implemented through regulations that exceeded the statutory authority. I argued this was ultra vires – beyond legal power. I also pointed out the practical absurdity: if a woman’s marriage made her unsuitable for public service, why was her unmarried cohabitation acceptable? The policy had no rational basis.

My supervisor, Clunies Ross, was unsympathetic. He seemed to view my objections as insubordination rather than legitimate legal concerns. When my pregnancy became obvious in 1951, the game was up. They demoted me to temporary status, revoked my pension contributions, and made it clear my services were no longer required.

Looking back, do you have any regrets about how you handled the situation?

I might have been more… diplomatic in my correspondence. I had a tendency to point out logical inconsistencies rather forcefully, which didn’t endear me to the administrators. But honestly, the principle was too important. If women were to have genuine equality in professional life, these discriminatory policies had to be challenged.

Would I have been more successful with a softer approach? Perhaps. But I wasn’t prepared to accept second-class treatment graciously. The science was too important, and frankly, I was too good at it to be sidelined by bureaucratic prejudice.

Tell us about one experiment that didn’t work as planned.

Oh, there were plenty of those. Early in 1947, I attempted to measure the polarisation of solar radio emission using a rotating dipole aerial. The theory was sound – if the emission originated from magnetised plasma, it should show circular or linear polarisation depending on the magnetic field geometry.

I spent weeks calibrating the system, accounting for instrumental effects, correcting for ionospheric Faraday rotation. The observations showed… absolutely nothing. No significant polarisation whatsoever.

I was convinced there was an equipment fault and spent another month rebuilding the entire receiving system. Same result. It wasn’t until years later that we understood solar radio emission mechanisms well enough to realise that thermal bremsstrahlung – the dominant process at 200 MHz – produces very weak polarisation. The effect was there, but far below our detection threshold.

The failure taught me to be more cautious about assumptions. Just because the physics predicts an effect doesn’t mean your apparatus is sensitive enough to measure it.

Some historians have questioned whether your contributions have been properly recognised. How do you respond to that?

It’s a fair point, though the situation’s more complex than simple gender discrimination. Yes, being a woman in physics meant I had to work twice as hard for half the recognition. But there were other factors too.

I never completed a PhD – there wasn’t time during the war, and afterwards I was too busy with the research itself. In an increasingly credential-conscious field, that mattered. My political views also made some colleagues uncomfortable. Being labelled “Red Ruby” didn’t help in the conservative postwar atmosphere.

But the real issue was timing. When Ryle received the Nobel Prize in 1974 for radio interferometry, I’d been out of the field for over twenty years. The marriage bar didn’t just end my career – it erased me from the historical narrative. Scientific recognition tends to follow continuous contribution, not pioneering work followed by forced exile.

What would you say to young women facing similar challenges today?

Document everything. Keep meticulous records of your contributions, your innovations, your discoveries. The institutional memory of science is frustratingly short, and women’s work has a particular tendency to be forgotten or attributed to male colleagues.

Don’t be afraid to claim credit for your ideas. I was sometimes too generous in collaborative papers, allowing my theoretical contributions to be understated. Modesty is not a virtue when it obscures your professional achievements.

Most importantly, find allies. Pawsey and the others who helped conceal my marriage weren’t just being kind – they recognised that good science transcends arbitrary social restrictions. Seek out mentors and colleagues who value competence over conformity.

How do you view the current state of radio astronomy?

It’s absolutely magnificent. The very long baseline interferometry, the massive arrays, the computational power – we’re seeing the universe in ways I could never have imagined. When I think that our crude 170-metre baseline has evolved into continent-spanning networks…

The discovery of pulsars particularly thrills me. Those precisely timed radio pulses are exactly the sort of phenomenon our interferometry techniques were designed to study. And the applications to cosmology, to understanding the structure of space-time itself – it’s rather beyond what any of us expected from pointing aerials at the sun.

Any final thoughts on your legacy?

I hope I’m remembered as someone who helped establish that radio waves could be a powerful tool for understanding the cosmos. The specific techniques matter less than the principle: that careful engineering combined with solid theoretical understanding can open entirely new windows on nature.

But I also hope my story serves as a reminder that scientific progress depends on institutional support for talent, regardless of gender, politics, or personal circumstances. How much more could I have contributed with another twenty years in the field? How many other women were lost to similar prejudices?

The universe is vast and complex. We need every capable mind working to understand it.

Letters and emails

Following our conversation with Ruby Payne-Scott, we’ve received an extraordinary response from readers worldwide who were moved by her story and eager to explore her insights further. From our growing community of letters and emails, we’ve selected five thoughtful questions that capture the curiosity of modern scientists, engineers, and advocates who want to learn more about her pioneering work, her resilience through institutional barriers, and the wisdom she might offer to those walking similar paths today.

Hana Al-Fulan, 34, Astrophysicist, Tokyo, Japan:

I’m fascinated by your decision to work at 200 MHz frequency for those early interferometry observations. What drove that specific choice – was it purely based on available equipment, or did you recognise certain advantages at that wavelength for solar observations? I’m curious whether you considered how ionospheric effects might impact your measurements at different frequencies.

Ah, that’s a cracking good question, Hana. The 200-megacycle choice wasn’t entirely arbitrary, though I’ll admit practicality played a large part initially. The wartime radar work had left us with rather robust receivers operating around that frequency – reliable kit that we knew inside and out. But there were solid scientific reasons for settling there as well.

You see, we’d been picking up these solar disturbances on various frequencies during the war, and it became apparent that 200 megacycles offered a sweet spot of sorts. Much higher – say, above 500 megacycles – and the solar emission becomes terribly weak during quiet periods. The thermal radiation from the sun’s chromosphere drops off quite sharply with frequency, following roughly the square law. Much lower – below 50 megacycles – and you’re battling frightful interference from terrestrial sources, not to mention the ionospheric complications you mentioned.

The ionosphere was indeed a concern, though perhaps not in the way you might expect. At 200 megacycles, we were well above the critical frequencies for normal ionospheric reflection – typically around 10 to 15 megacycles for the F-layer. This meant our signals weren’t being bounced about willy-nilly, which would have made interferometry quite impossible. However, we did have to account for ionospheric refraction, particularly during solar flares when the electron density increased dramatically.

I spent considerable time working out the refractive corrections. The ionospheric delay varies as the inverse square of frequency, so at 200 megacycles, the effect was manageable – typically a few degrees of phase shift, which we could measure and compensate for. Lloyd Berkner’s ionospheric predictions were invaluable here, though we often had to make real-time adjustments based on our own observations.

The frequency choice also gave us reasonable angular resolution without requiring impossibly long baselines. The 3-arcminute resolution we achieved with our 170-metre effective baseline was just sufficient to resolve major features on the solar disc. Higher frequencies would have improved resolution, certainly, but the received power would have been so weak we’d have struggled to detect anything but the strongest bursts.

There was another consideration – equipment stability. Crystal-controlled oscillators were more reliable at these intermediate frequencies than at higher ones. Maintaining phase coherence across the interferometer demanded extraordinary stability, and 200 megacycles represented a reasonable compromise between resolution, sensitivity, and technical reliability.

In hindsight, it was rather fortuitous. That frequency window proved ideal for studying the solar corona’s structure and dynamics – high enough to penetrate the lower atmosphere but low enough to maintain sufficient sensitivity for detailed observations.

Rafael Contreras, 28, Science Policy Researcher, Buenos Aires, Argentina:

What if the marriage bar hadn’t forced you out of research in 1951? Given your trajectory and the rapid advancement of radio astronomy in the 1950s and 60s, where do you think your work might have led? Do you think you would have pursued pulsar research, or were there other cosmic phenomena that particularly intrigued you?

That’s rather a haunting question, Rafael – one I’ve pondered many times over the years. By 1951, we were just beginning to understand that the radio sky was far richer than anyone had imagined. If I’d been allowed to continue, I suspect I would have pushed our interferometry techniques towards much larger arrays, probably long before Ryle’s Cambridge group got there.

The pulsars, discovered in ’67 by Jocelyn Bell – now there’s a woman who deserved far better recognition than she received – would have been absolutely irresistible. Those precise, rapid pulses were exactly the sort of phenomenon our time-resolution techniques were designed to study. I’d been working on millisecond timing measurements for solar burst analysis, so the leap to pulsar timing wouldn’t have been terribly difficult. The physics of neutron stars would have been fascinating – trying to understand how matter behaves under such extraordinary conditions.

But honestly, I think my heart would have remained with solar work for quite some time. By the early fifties, we were only scratching the surface of solar radio phenomena. The Type II bursts – those slow-drift events associated with shock waves – were crying out for detailed study. I had theories about how these shocks propagated through the corona, but we needed much better time and frequency resolution to test them properly.

I suspect I would have pushed hard for space-based observations too. The ionospheric limitations were becoming increasingly frustrating, particularly for low-frequency work. Getting receivers above the ionosphere would have opened up entirely new spectral windows. The lunar occultation technique was also terribly promising – watching radio sources disappear behind the moon’s limb could give you extraordinary angular resolution without massive ground-based arrays.

The real tragedy is what we might have learned about space weather. My work on solar radio bursts was directly relevant to understanding how solar disturbances affect Earth’s magnetosphere. By the sixties, when satellites were becoming routine, radio astronomy could have made crucial contributions to predicting geomagnetic storms. Lives and equipment might have been saved with better forecasting.

There was also the broader question of stellar radio emission. If the sun produced such varied radio phenomena, what about other stars? The sensitivity improvements through the fifties and sixties would have made stellar radio astronomy possible much earlier. We might have discovered radio emission from flare stars, or even early hints of the cosmic radio background that Penzias and Wilson stumbled upon.

The field evolved so rapidly after I left – it’s both thrilling and rather heartbreaking to contemplate what might have been.

Greta Nilsson, 41, Engineering Ethics Professor, Stockholm, Sweden:

Your experience highlights how institutional policies can waste scientific talent, but I’m wondering about the personal cost of fighting these systems. How did you maintain your sense of scientific identity during those decades away from research? Did you find ways to stay intellectually connected to astronomy, and what sustained your passion for physics through those years of exclusion?

Greta, that’s perhaps the most difficult question you could ask. The personal cost was… well, it was rather like losing a limb, if I’m honest. For nearly two decades, I’d defined myself through my work – the elegant mathematics, the thrill of discovery, the satisfaction of solving technical puzzles. Suddenly, I was expected to find fulfilment in domestic arrangements and motherhood alone.

Don’t misunderstand me – I adored my children, Peter and Fiona. Watching them grow and learn provided genuine joy. But it didn’t fill the intellectual void. I found myself reading Nature and the Astrophysical Journal religiously, following developments in radio astronomy like following news of old friends. Bill understood, bless him. He’d bring home technical papers from his own work, knowing I’d devour them.

Teaching mathematics at various schools helped enormously. Working through complex problems with bright students kept my mind sharp. I particularly enjoyed the advanced trigonometry classes – there’s something deeply satisfying about watching a student suddenly grasp the elegance of spherical geometry. It wasn’t research, but it was intellectually demanding work with young minds eager to learn.

I maintained correspondence with several colleagues, particularly those who’d worked with me during the early interferometry days. They’d send preprints occasionally, ask my opinion on technical matters. It was rather like being a ghost haunting the scientific community – present but not acknowledged.

The hardest moments came when reading about discoveries that built directly on our early work. Seeing techniques we’d pioneered being developed and refined by others, without being able to contribute to the advances… it was maddening. I’d find myself working through problems in my head, developing improvements to methods I’d helped create, with no avenue to share these insights.

What sustained me was stubborn pride, really. I refused to accept that my enforced exile diminished the value of what I’d accomplished. The physics remained true regardless of bureaucratic nonsense. Mathematics doesn’t care about marriage certificates. The interference patterns we’d measured at Dover Heights were permanent contributions to human knowledge, whatever the administrators thought of my domestic arrangements.

I also drew strength from watching other women slowly breaking down similar barriers. When I saw Marie Tharp mapping the ocean floor, or Katherine Johnson calculating orbital trajectories for NASA, it reminded me that progress was possible, even if painfully slow.

The passion never died, Greta. It simply went underground, waiting for opportunities to surface. Even now, discussing these old problems with you, I can feel that familiar excitement stirring. Some flames burn too brightly to be extinguished by institutional prejudice.

Jackson Hayes, 38, Science Communication Writer, Toronto, Canada:

You mentioned being called ‘Red Ruby’ due to your political views, which seems to have compounded the discrimination you faced. I’m curious about how your broader worldview influenced your approach to science. Did your political consciousness shape how you thought about the democratisation of knowledge, or the responsibility of scientists to challenge unjust systems within their own institutions?

Jackson, that nickname was rather a badge of honour, actually, though I suspect it wasn’t meant as such. My political views weren’t terribly radical by today’s standards – I simply believed that knowledge belonged to humanity, not to governments or corporations hoarding it for strategic advantage.

The war taught me how easily scientific work becomes militarised. We developed radar techniques to save Allied lives, which was entirely proper. But afterwards, watching how civilian research became entangled with Cold War secrecy… well, it troubled me greatly. Science progresses through open exchange of ideas, not through classification stamps and security clearances.

I was quite vocal about this during the late forties. When the government began restricting publication of certain research, I argued that Australian science would suffer if we adopted American-style security measures. Knowledge shared freely advances faster than knowledge locked away in filing cabinets. The solar radio work proved this – our observations were immediately useful to researchers worldwide because we published everything openly.

My political consciousness absolutely shaped how I viewed scientific institutions. The marriage bar wasn’t just personal discrimination – it was symptomatic of broader social hierarchies that wasted human potential. If society discarded half its intellectual talent based on gender, what other brilliant minds were being squandered due to class, race, or political beliefs?

I spoke out about university admission policies too. Too many bright working-class students were excluded from higher education simply because their families couldn’t afford fees. Science needs diverse perspectives, not just the sons of professional families. Some of my most capable students came from quite modest backgrounds – their hunger for knowledge often exceeded that of more privileged classmates.

The atomic bomb complicated everything, didn’t it? Suddenly, scientific knowledge carried terrifying responsibilities. I felt strongly that scientists had obligations beyond their research – we needed to speak publicly about the implications of our work. When colleagues remained silent about weapons development or environmental damage, I considered it moral cowardice.

This put me at odds with administrators who preferred scientists to remain politically neutral. But neutrality itself is a political position, Jackson. Claiming to be apolitical often means accepting existing power structures uncritically.

I believed – still believe – that scientific institutions should model the democratic ideals they claim to serve. Merit should matter more than connections, evidence more than authority, and human welfare more than institutional prestige. If scientists won’t challenge unjust systems within their own organisations, how can we expect to address larger social problems?

Perhaps that made me difficult to manage. I certainly wasn’t prepared to keep quiet about inequities I witnessed daily. Science is too important to be left entirely to the scientists – especially when those scientists are chosen primarily for their willingness to conform.

Chika Obi, 29, Radio Engineering PhD Student, Lagos, Nigeria:

The swept-lobe interferometer you developed sounds remarkably sophisticated for 1949. I’d love to understand more about the mechanical aspects – how did you achieve those rapid oscillations of the aerial whilst maintaining the precision needed for interferometry? Were there particular engineering challenges in synchronising the mechanical motion with the electrical signal processing that modern digital systems have made obsolete?

Chika, you’ve hit upon one of the trickiest bits of engineering we tackled! The swept-lobe system was rather like conducting an orchestra where half the instruments are mechanical and half electrical – getting them to play in harmony required considerable ingenuity.

The basic principle was straightforward enough: we oscillated one of our Yagi aerials through a small arc – about 10 degrees either side of centre – at roughly 50 cycles per second. This created a moving interference pattern that could track solar radio sources as they drifted across the sky. But the devil, as they say, was in the details.

The mechanical drive system was the real challenge. We couldn’t use simple motors – the oscillation had to be perfectly sinusoidal to maintain proper phase relationships. Alec Little and I settled on a cam-driven mechanism powered by a synchronous motor running off the mains frequency. The cam profile was mathematically calculated to produce true harmonic motion, machined to tolerances that would make a clockmaker proud.

The synchronisation problem you mention was absolutely crucial. We needed to know the exact aerial position at every instant to properly interpret the interference signals. Our solution was rather elegant – we attached a small potentiometer to the drive mechanism, creating a voltage that varied sinusoidally with aerial position. This reference signal was fed into the same recording equipment as our radio observations, giving us perfect timing correlation.

The phase stability requirements were frightful. Any play in the mechanical linkages would introduce random phase errors that would completely corrupt our measurements. We used precision ball bearings throughout, with carefully adjusted preloading to eliminate backlash. The aerial mounting had to be rigid enough to maintain pointing accuracy yet flexible enough to oscillate smoothly dozens of times per second.

Temperature compensation was another headache. Metal expansion would shift the electrical path lengths between the moving and stationary aerials, throwing off our phase measurements. We solved this by using matched coaxial cables of identical length for both signal paths, routing them through similar temperature environments.

The most delicate aspect was calibrating the entire system. We’d observe known radio sources – particularly the strong galactic noise from Sagittarius – to verify that our mechanical motion wasn’t introducing spurious signals. Any resonances in the structure would show up as false periodicities in the data.

You’re quite right that modern digital processing makes much of this obsolete. Today you’d simply use electronic beam steering with phased arrays – no moving parts whatsoever. But there was something deeply satisfying about watching that aerial swing back and forth, knowing we were mechanically scanning the radio sky in real time. Pure nineteenth-century engineering married to twentieth-century electronics!

Reflection

Ruby Payne-Scott passed away on 25th May 1981 at age 69, just as the radio astronomy she helped create was revealing pulsars, quasars, and the cosmic microwave background – discoveries that vindicated her belief that the radio sky held extraordinary secrets waiting to be unlocked.

Our conversation reveals a woman whose technical brilliance was matched by her moral clarity about science’s purpose and potential. Her insistence that knowledge belongs to humanity, not to governments or institutions hoarding it for advantage, feels remarkably prescient in today’s debates about open science and artificial intelligence governance. The swept-lobe interferometer’s elegant marriage of mechanical precision and electronic innovation embodies the kind of resourceful problem-solving that modern researchers, with their vast computational resources, sometimes overlook.

What emerges most powerfully is Payne-Scott’s refusal to accept that institutional discrimination could diminish the value of her contributions. Where historical accounts often focus on her as a victim of the marriage bar, she presents herself as a defiant intellectual force who chose principle over pragmatism. Her technical explanations reveal depths of innovation – particularly in ionospheric correction and phase stability – that weren’t fully documented in the official record.

Uncertainties remain about her classified wartime work and the extent of her theoretical contributions to solar radio physics, much of which was never published due to her forced departure. Yet her legacy lives on in unexpected ways: the Square Kilometre Array uses interferometric principles she pioneered, space weather prediction relies on solar radio monitoring techniques she developed, and her advocacy for open scientific communication resonates in today’s preprint servers and collaborative research platforms.

Perhaps most significantly, Payne-Scott’s story illuminates how scientific progress depends not just on individual brilliance, but on institutions that nurture and retain talent regardless of gender, politics, or personal circumstances. As she reminds us, the universe is vast and complex – we need every capable mind working to understand it. Her voice, silenced too early by bureaucratic prejudice, continues to challenge us to build more inclusive scientific communities worthy of the cosmos we seek to explore.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview represents a dramatised reconstruction based on extensive historical research into Ruby Payne-Scott‘s life, work, and documented statements. While grounded in factual accounts from scientific papers, archival materials, biographical sources, and historical records, the dialogue and personal reflections are imagined interpretations designed to bring her story and contributions to life for contemporary readers. We have endeavoured to remain faithful to her known technical work, documented experiences with institutional discrimination, and the scientific context of her era, whilst acknowledging that any reconstruction of historical voices involves creative interpretation alongside scholarly research.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved. | 🌐 Translate

Leave a comment