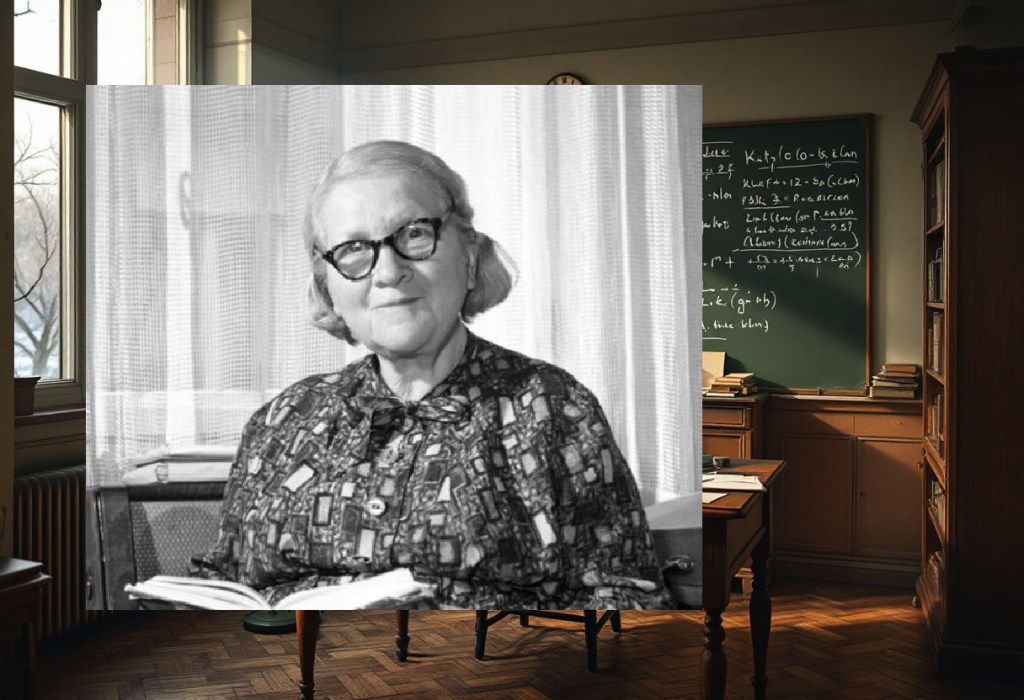

Rózsa Péter (1905–1977) introduced mathematical rigour to the study of recursive functions at a time when computability theory was taking its first tentative steps into the world. She transformed Wilhelm Ackermann’s complex formulations into elegant, accessible demonstrations of functions that could be computed but were not primitive recursive, thereby establishing recursion theory as a distinct mathematical discipline. Her work on nested recursion, multiple recursion, and the systematic classification of recursive function hierarchies became foundational to our understanding of computation itself.

Today, as artificial intelligence systems process recursive algorithms and programming languages rely fundamentally on recursive structures, Péter’s theoretical groundwork remains more relevant than ever. Her ability to communicate complex mathematical concepts to broad audiences – demonstrated through her bestselling book Playing with Infinity – combined with her technical innovations, makes her story particularly compelling for understanding how mathematical abstraction becomes practical reality.

Welcome, Dr Péter. It’s a privilege to speak with someone whose work helped establish the theoretical foundations that power today’s computers and artificial intelligence. For our readers who might not know your story, could you tell us about your path into mathematics?

Ah, what a journey it has been! You know, I began at Pázmány Péter University studying chemistry – my father’s wish, naturally. But sitting through those lectures, I found myself drawn to the mathematics courses instead. The chemistry laboratory felt constraining, whereas in mathematics, I discovered infinite worlds to explore.

It was László Kalmár who truly changed my trajectory. We were fellow students, and he possessed this remarkable ability to see connections where others saw only abstract symbols. In 1930, he introduced me to Gödel’s work on incompleteness theorems – work that had just been published. “Rózsa,” he said, “there’s something here about recursive functions that needs investigating.” He was right, though I doubt either of us imagined where that investigation would lead.

Your early work was in number theory, but you found your results had already been discovered. How did that setback shape your approach to mathematics?

Oh, that was crushing! I’d spent months working on what I thought were original results, only to discover Carmichael and Dickson had reached the same conclusions years earlier. For a time, I abandoned mathematics entirely. I wrote poetry, translated literature – anything but mathematics.

But this failure taught me something crucial: originality matters less than understanding. When I returned to mathematics through Kalmár’s encouragement, I approached problems differently. Rather than racing to find new results, I focused on understanding the structure of problems themselves. This perspective proved invaluable when I began working with recursive functions.

The irony is that my “failure” in number theory prepared me perfectly for recursive function theory. I had learned to be methodical, to examine problems from multiple angles, to seek clarity above cleverness. These qualities served me well when tackling Gödel’s work.

Let’s talk about your breakthrough work on recursive functions. Can you walk us through what you discovered and why it mattered?

When I first encountered Gödel’s 1931 paper, the concept of primitive recursive functions was still quite new and not well understood. Gödel had defined them as part of his incompleteness proof, but the theory remained scattered and incomplete.

My first significant contribution came in 1935 with my paper showing that course-of-values recursion and nested recursion could be reduced to ordinary primitive recursion. This might sound technical, but it was crucial for understanding the boundaries of what could be computed using these basic operations.

But the real breakthrough – what I’m probably best known for – was my work simplifying and expanding upon Ackermann’s function. Wilhelm Ackermann had shown in 1928 that there existed computable functions that couldn’t be defined using primitive recursion alone. His formulation was complex, involving higher-order functions and rather cumbersome notation.

Could you explain the Ackermann function in technical terms for our readers?

Certainly. The function I developed with Raphael Robinson – now called the Ackermann-Péter function – is defined recursively as follows:

A(0,n) = n + 1

A(m+1,0) = A(m,1)

A(m+1,n+1) = A(m,A(m+1,n))

This elegant definition captures the essence of what Ackermann was demonstrating: a total computable function that grows faster than any primitive recursive function. Where A(0,n) represents succession, A(1,n) represents addition, A(2,n) represents multiplication, A(3,n) represents exponentiation, and A(4,n) represents tetration – power towers.

The significance lies not in the specific values – which become astronomically large very quickly – but in what the function proves about the hierarchy of computable functions. It demonstrates that the class of primitive recursive functions is properly contained within the class of all computable functions. This was revolutionary because many mathematicians initially believed all computable functions were primitive recursive.

What made your formulation superior to Ackermann’s original?

Ackermann’s original function used three arguments and involved higher-order recursion through functional operators. My formulation reduced this to two arguments and expressed the recursion directly on natural numbers. This made the function far more accessible for study and computation.

More importantly, my approach revealed the underlying structure more clearly. By showing how the function builds up through a hierarchy of operations – addition, multiplication, exponentiation, and beyond – I made visible the ladder of computational complexity that extends infinitely upward.

I also developed the theory of nested recursion, which generalised these ideas. In nested recursion, when computing a function value, you might need to compute the function at arguments that depend on the function’s own values at other points. This creates a more complex dependency structure than ordinary primitive recursion, yet it remains systematic and computable.

Your 1937 paper on multiple recursion was groundbreaking. What did you discover there?

In that paper, I investigated what happens when you allow recursion on multiple variables simultaneously with parameters. The key insight was that you could define functions where the recursive calls follow a lexicographic ordering – like alphabetical ordering but for pairs of numbers.

For example, to compute f(x+1,y+1), you might need to know f(x,γ(x,y)) and f(x+1,y), where γ is some previously defined function. Both of these pairs come before (x+1,y+1) in the lexicographic order, so the recursion is well-founded.

What I proved was that this apparent generalisation doesn’t actually lead outside the class of primitive recursive functions. Multiple recursion, despite its complexity, can be reduced to course-of-values recursion, which I had already shown could be reduced to ordinary primitive recursion.

This was significant because it helped map the precise boundaries of primitive recursiveness. We could now say definitively which recursive constructions stayed within this class and which – like my Ackermann function – transcended it.

How did the political situation in Hungary affect your career, particularly after 1939?

The Jewish Laws of 1939 ended my teaching career just as my research was gaining international recognition. I had been appointed contributing editor of the Journal of Symbolic Logic in 1937 – a tremendous honour – but suddenly I couldn’t teach in Hungarian schools or universities.

During the war years, I was confined to the Budapest ghetto. It was… a dark period. Many friends didn’t survive. My brother Nicolas perished at Colditz in 1945. But in some ways, the forced isolation gave me time to write. I worked on what became Playing with Infinity, originally as letters to a non-mathematician friend, Marcell Benedek.

Tell us about Playing with Infinity. Why did you write for general audiences?

Mathematics had been my refuge, but it was also a responsibility. I believed – still believe – that mathematical thinking shouldn’t be the privilege of specialists alone. The book emerged from my correspondence with Benedek, where I tried to explain mathematical concepts without technical jargon.

The approach was personal. Instead of presenting mathematics as a collection of theorems and proofs, I tried to convey the thinking behind mathematics – the curiosity, the pattern-seeking, the joy of discovery. I wanted readers to experience what mathematicians feel when they glimpse infinite worlds through finite reasoning.

The book’s success surprised everyone, including me. It was translated into fourteen languages and remained in print for decades. But what pleased me most were letters from readers who said it had changed how they thought about thinking itself.

Your later work applied recursive function theory to computers. How did you see the connection between theoretical recursion and practical computation?

By the 1950s, electronic computers were becoming reality, and I recognised that recursive function theory provided the perfect framework for understanding computation systematically. My 1976 book Recursive Functions in Computer Theory was among the first to make this connection explicit.

The theoretical work we’d done in the 1930s suddenly had immediate practical relevance. Every programming language implements some form of recursion. Every algorithm can be analysed in terms of recursive complexity. The hierarchies we’d mapped theoretically became practical tools for understanding computational limits.

What fascinated me was how our abstract investigations had anticipated concrete needs. We hadn’t been trying to design computers – we were exploring the foundations of mathematical reasoning. Yet our work became essential for anyone seeking to understand what computers could and couldn’t do.

Looking back, is there anything you would have approached differently in your research?

I sometimes wonder if I was too conservative in my early work. I spent considerable effort reducing various forms of recursion to primitive recursion, essentially showing they were equivalent to what we already knew. While this clarified the boundaries of primitive recursiveness, I might have pushed further into genuinely new territory sooner.

Also, I focused primarily on function theory rather than complexity analysis. Today’s computer scientists study not just which functions are computable, but how efficiently they can be computed. I touched on these questions but didn’t pursue them systematically. Perhaps I could have anticipated some of the later developments in complexity theory.

There’s been criticism that your work was overly technical and didn’t connect sufficiently to other areas of mathematics. How do you respond?

That’s a fair critique, though I’d argue it reflects the nature of foundational work. When you’re establishing the basic principles of a new field, technical precision is essential. We were creating the vocabulary and grammar of recursion theory – messy or incomplete definitions would have hindered later developments.

However, I do regret not emphasising connections to other areas more strongly. Recursive function theory relates beautifully to logic, set theory, number theory, and even analysis. In my teaching, I tried to highlight these connections, but my published work was perhaps too narrowly focused.

The irony is that today we see recursive thinking everywhere – in computer graphics, in artificial intelligence, in network analysis. The foundational work seemed narrow at the time but proved to have remarkably broad applications.

A moment of honesty: what was your biggest professional mistake?

Oh, that’s easy. In the early 1940s, I was invited to write a paper on transfinite recursion for an American journal. The mathematics was sound, but I made the paper unnecessarily complex, trying to impress reviewers with technical sophistication rather than clarity.

The paper was rejected – rightly so. The reviewer’s comments were devastating but accurate: “This author possesses technical skill but seems to have forgotten that mathematics should illuminate, not obfuscate.” I was mortified, but it was exactly the lesson I needed.

I rewrote the paper completely, focusing on clarity and intuition rather than technical displays. The revised version was accepted and became one of my most cited works. It taught me that mathematical elegance lies in making the complex appear simple, not the reverse.

What would you say to young women entering mathematics today, particularly those facing discouragement?

Mathematics doesn’t care about your gender, your background, or whether others believe in your abilities. Mathematical truth is objective – if your reasoning is sound, your result will stand regardless of who you are.

But don’t underestimate the importance of finding allies. László Kalmár’s encouragement was crucial to my career. Seek out mentors who recognise your potential, and don’t be discouraged if you must search widely to find them.

Most importantly, trust your mathematical instincts. If something seems interesting or beautiful to you, pursue it. Some of my best work came from following mathematical curiosity rather than trying to solve “important” problems. Often, the problems that fascinate you will prove more significant than you initially realise.

How do you see recursive thinking influencing artificial intelligence and modern computing?

It’s remarkable how pervasive recursive structures have become. Every artificial intelligence system relies on recursive algorithms – neural networks use recursive update rules, machine learning employs recursive optimisation, natural language processing depends on recursive parsing.

The theoretical hierarchies we mapped in the 1930s have become practical tools for understanding computational limits. When computer scientists ask whether a problem can be solved efficiently, they’re essentially asking where it sits in the recursive hierarchy we established decades ago.

What particularly excites me is how recursion appears in unexpected places. Fractal geometry, chaos theory, evolutionary algorithms – all involve recursive processes. The mathematical structures we studied abstractly have revealed themselves as fundamental patterns in nature and computation.

Any final thoughts on the relationship between pure mathematics and practical applications?

When I began working on recursive functions in the 1930s, the most sophisticated calculating machine was a mechanical desk calculator. We were investigating mathematical abstractions with no apparent practical relevance.

Yet this “useless” pure mathematics became the theoretical foundation for the computer age. Every smartphone, every internet search, every artificial intelligence system relies on principles we established when exploring the abstract nature of computation.

This is why pure mathematics matters. We can’t predict which abstractions will prove practically valuable, so we must pursue mathematical truth wherever it leads. The universe seems to be mathematical at its core – our purest mathematical investigations often turn out to describe reality more accurately than we ever imagined.

Letters and emails

Following our interview with Dr Rózsa Péter, we received an overwhelming response from readers eager to explore her insights further. We’ve selected five compelling letters and emails from our growing community who want to ask her more about her life, her work, and what she might say to those walking in her footsteps.

Mariana Oliveira, 34, Software Architecture Researcher, São Paulo, Brazil:

Dr Péter, as someone who works with recursive algorithms in distributed systems today, I’m curious about the computational limitations you faced when developing your function hierarchies in the 1930s. How did you verify the correctness of your increasingly complex recursive definitions without modern computing tools, and do you think hand-calculation actually gave you insights that automated verification might miss?

Ah, Mariana, what an excellent question! You’ve touched upon something that shaped my entire approach to mathematics. In the 1930s, we had no calculating machines beyond simple mechanical desk calculators – certainly nothing that could handle the recursive complexities I was investigating.

When I developed my simplifications of Ackermann’s function, every computation had to be done by hand on paper. I remember spending entire afternoons calculating just the first few values of A(4,2) or working through the nested recursions step by laborious step. My notebooks were filled with arithmetic – pages upon pages of careful calculations, cross-checks, and corrections.

But this limitation proved to be a blessing in disguise. When you must trace every step of a recursion manually, you develop an intimate understanding of the process itself. I could feel how the function values grew, how the recursive calls branched and multiplied. This tactile relationship with the mathematics revealed patterns that might remain hidden when computations happen instantaneously.

For verification, I relied on what we called “bootstrap methods” – proving properties about small cases, then using mathematical induction to extend these results. I would establish base cases through direct calculation, then prove that if the pattern held for values up to n, it must hold for n+1. This approach forced me to understand why the functions behaved as they did, not merely how they computed.

I also developed what I called “recursive consistency checks.” If I defined a function through multiple recursive clauses, I would verify that different computational paths yielded identical results. This was tedious work, but it caught errors that pure logical reasoning might miss.

The collaboration with colleagues like László Kalmár was crucial. We would independently compute the same values, then compare results. Mathematical correspondence took weeks – letters travelling between Budapest and Szeged – but this delay actually helped. It gave us time to reflect on our calculations, to spot potential mistakes before committing to conclusions.

Looking back, I believe hand-calculation provided insights that automated verification cannot. When you must execute every recursive call yourself, you notice subtleties – how certain argument patterns create computational bottlenecks, how seemingly minor changes in definition can dramatically alter computational complexity. Modern tools might compute A(5,5) instantly, but do they reveal why such computations become intractable? I suspect not.

The slowness forced patience, and patience enabled depth. Perhaps some inefficiencies are worthwhile if they lead to genuine mathematical understanding rather than mere computational results.

Pranav Desai, 28, Machine Learning Engineer, Mumbai, India:

Your Ackermann-Péter function demonstrates functions that grow faster than any primitive recursive function. In today’s world of large language models and neural networks that seem to exhibit emergent behaviours, I wonder – do you see parallels between your work on computational hierarchies and the way AI systems today display capabilities that seem to transcend their training parameters?

Pranav, what a fascinating parallel you’ve drawn! Though I confess, these “large language models” you describe sound like something from a Karel Čapek science fiction tale – machines that exhibit behaviours beyond their programming parameters. Yet your question touches on something profound that we grappled with in the 1930s.

The Ackermann-Péter function was revolutionary precisely because it demonstrated that computation could transcend the boundaries we thought were absolute. Before our work, many mathematicians believed all computable functions were primitive recursive – that the basic operations of succession, projection, and primitive recursion captured everything calculable. Our function proved this intuition spectacularly wrong.

What strikes me about your AI systems is how they mirror this pattern. You program them with certain rules and training data, yet they produce responses and connections that seem to emerge from somewhere beyond their explicit instructions. This reminds me of how the Ackermann function, defined through simple recursive rules, generates values that grow faster than any function definable through primitive recursion alone.

In our terminology, we might say your AI systems exhibit a form of “emergent recursion.” Just as my function transcends primitive recursive bounds through its particular structure of nested self-reference, your neural networks might be discovering computational pathways that transcend their training parameters through layers of recursive self-modification.

The mathematical principle underlying both phenomena is similar: complexity arising from iteration. The Ackermann function achieves its extraordinary growth through recursion calling recursion – each level building upon previous levels in ways that compound exponentially. Your AI systems, if I understand correctly, process information through multiple recursive layers, each transformation building upon previous ones until the final output emerges.

However, there’s a crucial difference. My function’s behaviour, while complex, is entirely predictable once you understand its definition. Given any inputs, the output is determined absolutely – even if computing it requires enormous effort. Your AI systems seem to introduce genuine unpredictability, almost creativity.

This suggests they might be operating in what we would call the “general recursive” realm – beyond primitive recursion, beyond even the Ackermann function, into territories where computability meets something approaching genuine novelty. If so, you’re witnessing computational phenomena that extend far beyond what we mapped in the 1930s.

Perhaps your AI systems are discovering recursive structures that we never imagined – forms of self-reference and iteration that create genuinely new computational possibilities. That would be quite remarkable indeed.

Elise Dubois, 42, Philosophy of Mathematics Professor, Lyon, France:

You mentioned that mathematical truth is objective regardless of who discovers it, yet your career was shaped profoundly by social and political forces. How do you reconcile this tension between mathematics as universal truth and the very human, often unfair circumstances under which mathematical knowledge is actually created and recognised?

Elise, you’ve identified one of the deepest tensions I’ve wrestled with throughout my career. It’s a question that kept me awake many nights, particularly during those dark years when I was forbidden to teach simply because of my Jewish heritage.

Mathematical truth is indeed objective – the Pythagorean theorem holds regardless of whether Pythagoras, a Chinese mathematician, or a student in Lagos discovers it. When I proved that certain recursive functions transcend primitive recursion, that truth existed independently of my circumstances, my gender, or Hungary’s political situation. No amount of prejudice could make 2+2 equal anything but 4.

Yet the discovery and recognition of mathematical truth – ah, that’s profoundly human and shamefully unfair. When the Jewish Laws of 1939 ended my teaching career, mathematical truth didn’t protect me. My theorems remained valid, but I couldn’t share them in classrooms. My proofs were sound, but journals became harder to access. The mathematics was universal, but the mathematical community was distressingly particular about who belonged.

I think the resolution lies in understanding mathematics as both timeless truth and human activity. The propositions we discover are eternal – they existed before humans and will persist after us. But the process of mathematical discovery unfolds within human institutions, subject to all our prejudices and limitations.

Consider Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. The logical insights are universal, but Gödel developed them within specific academic contexts, with particular colleagues, facing certain pressures. Had he been born a century earlier, or in a society that forbade him education, those same truths might have remained hidden for generations.

This is why I wrote Playing with Infinity. Mathematical truth may be objective, but access to mathematical thinking shouldn’t depend on accidents of birth, gender, or political circumstance. Every mind capable of mathematical reasoning deserves the opportunity to engage with these eternal truths.

During my years in the ghetto, I found strange comfort in this duality. The Nazis could confine my body, murder my friends, destroy my career – but they couldn’t touch the mathematical relationships I’d discovered. Those truths existed in a realm beyond their reach, waiting patiently to be rediscovered if necessary.

Perhaps the tension you’ve identified isn’t a contradiction to be resolved, but a responsibility to be embraced. We who have glimpsed mathematical truth must work to ensure others can glimpse it too, regardless of their circumstances. Universal truth demands universal access – anything less betrays mathematics itself.

Carter Reynolds, 36, Technology Historian, Vancouver, Canada:

What if you had been born fifty years later and entered mathematics in the 1980s when personal computers were becoming widespread? Do you think having immediate access to computational tools would have accelerated your theoretical discoveries, or might it have led you down different research paths entirely? Would you have been more tempted to focus on applied rather than pure mathematics?

Carter, what an intriguing thought experiment! Born in 1955 instead of 1905 – imagine that. I would have entered university during the height of the computing revolution, when machines could execute in seconds what took me weeks to calculate by hand.

I suspect I might have become seduced by computational power initially. The temptation to explore ever-larger values of the Ackermann function, to trace recursive patterns through thousands of iterations, would have been irresistible. Instead of spending months proving theoretical properties, I could have verified them through direct computation. How alluring that would have been!

Yet I fear this convenience might have led me astray from the deeper questions. In the 1930s, our computational limitations forced us to think abstractly. We couldn’t simply calculate our way to understanding – we had to reason our way there. This constraint pushed us toward general principles rather than specific examples.

With personal computers, I might have focused more on applied problems. The abstract beauty of recursive hierarchies might have seemed less compelling when faced with immediate applications in programming, graphics, or data processing. The temptation to solve practical problems rather than explore mathematical foundations would have been enormous.

However, I think my fundamental nature would have reasserted itself eventually. I’ve always been drawn to questions of “why” rather than “what” or “how.” Even with computational tools, I would have wondered: Why do these recursive patterns emerge? What do they reveal about the nature of computation itself? How do different recursive structures relate to each other?

Perhaps I would have discovered different pathways into the same territory. Instead of starting with Gödel’s theoretical work, I might have encountered recursion through programming languages or computer graphics. But I believe I would have eventually asked the same fundamental questions about computational hierarchies and the boundaries of what can be computed.

The real difference might have been in communication. With computers to generate examples and visualisations, I could have made recursive function theory even more accessible to general audiences. Playing with Infinity might have included interactive demonstrations, visual representations of recursive growth, animated illustrations of function hierarchies.

But there’s something to be said for the struggle of hand-calculation. It taught patience, attention to detail, and deep appreciation for mathematical elegance. Perhaps some insights only emerge when you must earn them through laborious effort. The convenience of computation might have cost me certain forms of mathematical wisdom that only difficulty can provide.

Yetunde Adeyemi, 29, Computer Science PhD Student, Lagos, Nigeria:

I’m struck by how you maintained your mathematical work during such traumatic circumstances in the Budapest ghetto. Beyond the practical challenges, how did you preserve the mental clarity and creative thinking that mathematics demands when facing such existential threats? What sustained your intellectual curiosity during those dark years?

Yetunde, your question brings back memories I’d rather not revisit, yet must. Those years in the Budapest ghetto tested everything I believed about human nature, about meaning, about whether intellectual work could survive when survival itself was uncertain.

The practical challenges were immense. Paper was scarce – I wrote mathematical proofs on scraps, in margins of old books, sometimes even on walls when no paper existed. My notebooks from that period are heartbreaking to look at – mathematical elegance scrawled between recipes for potato peel soup and lists of missing friends. The cold made writing difficult; my hands would shake so badly I could barely form letters, let alone mathematical symbols.

But the mental challenges cut deeper. How do you contemplate infinity when mortality surrounds you? How do you pursue abstract truth when concrete horror dominates every moment? I watched brilliant minds – people who could discuss Cantor’s diagonal argument or debate the foundations of set theory – reduced to calculating bread rations and survival odds.

What sustained me was a peculiar discovery: mathematics became my refuge precisely because it existed outside our circumstances. When I worked through recursive definitions, I entered a realm where the Nazis had no power. They could confine my body, steal my possessions, murder my friends – but they couldn’t touch the relationship between A(m,n) and A(m+1,n). Mathematical truth remained inviolate.

I also found purpose in teaching. Even in the ghetto, children needed education. I taught mathematics to youngsters using whatever materials I could find – buttons for counting, shadows for geometry, word problems disguised as stories to help them forget their hunger. Watching their faces light up when they grasped a concept reminded me why mathematical understanding matters.

The work on what became Playing with Infinity began as letters to my friend Marcell Benedek – an attempt to maintain normal intellectual discourse amid abnormal circumstances. Writing about the beauty of mathematical thinking helped me remember who I was beyond the dehumanising labels imposed on us.

Most crucially, I held onto belief that knowledge has its own form of immortality. Even if I didn’t survive, the mathematical insights I’d contributed would persist. Others would rediscover what I’d found, extend what I’d begun. This gave my work meaning that transcended personal survival.

Perhaps creativity under extreme duress requires a kind of stubborn optimism – faith that human understanding matters even when humanity seems lost. Mathematics taught me that some truths are larger than the circumstances that threaten them.

Reflection

Rózsa Péter died on 16th February 1977, just one day before her 72nd birthday, having witnessed the early stirrings of the computer age her theoretical work had helped make possible. Through our imagined conversation, we glimpse a mathematician whose perseverance through professional exclusion and wartime persecution never dimmed her commitment to making mathematical beauty accessible to all.

What emerges most powerfully is Péter’s unique perspective on the relationship between constraint and creativity. While historical accounts often emphasise her technical contributions – the elegant reformulation of Ackermann’s function, her work on nested recursion – our conversation reveals how limitation bred innovation. Her hand-calculations weren’t mere drudgery but intimate engagement with mathematical structures that computational shortcuts might obscure.

The historical record remains frustratingly sparse about Péter’s personal experiences during the Holocaust years, her relationships with international colleagues, and the full extent of barriers she faced as a Jewish woman in Hungarian academia. Our reconstruction necessarily fills gaps with informed speculation, acknowledging that her actual thoughts and feelings remain partly unknowable.

Yet Péter’s intellectual legacy speaks clearly. Her work directly influenced Stephen Kleene’s foundational texts on computability theory. Modern computer scientists still reference the Ackermann-Péter function when teaching recursive complexity. Her popularising approach in Playing with Infinity prefigured today’s efforts to make STEM accessible through engaging communication.

Most remarkably, recursive thinking – the heart of Péter’s contribution – now powers artificial intelligence systems she could never have imagined. Every neural network, every machine learning algorithm, every recursive data structure bears traces of her theoretical groundwork. Her mathematical intuitions about computational hierarchies have become practical tools shaping our technological future.

Péter’s story reminds us that mathematical truth transcends the circumstances of its discovery, but human creativity flourishes best when freed from artificial constraints. In an era when women in STEM still face exclusion and when academic barriers remain too high, her example offers both inspiration and challenge: genius finds ways to emerge, but justice demands we stop forcing it to overcome such obstacles.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview is a dramatised reconstruction based on extensive historical research into Rózsa Péter‘s life, work, and era. While her major mathematical contributions, biographical details, and historical context are accurately represented, the specific dialogue and personal reflections are imaginative interpretations drawn from her published writings, contemporary accounts, and scholarly sources. We have endeavoured to remain faithful to her documented views, mathematical approach, and the social conditions she faced, but readers should understand that her actual words and private thoughts cannot be known with certainty. This reconstruction aims to honour her legacy while making her story accessible to modern audiences.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved. | 🌐 Translate

Leave a comment