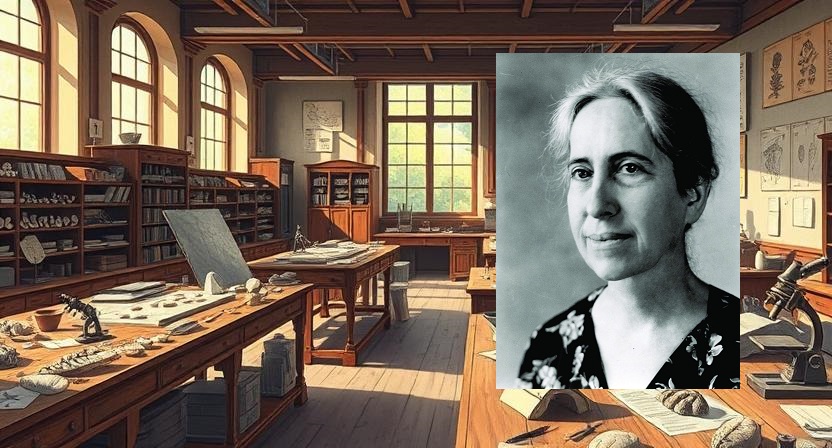

Winifred Goldring (1888-1971) transformed our understanding of Earth’s earliest forests, using meticulous fieldwork and innovative museum exhibits to reveal the planet’s botanical past to both scientists and the public. She broke through institutional barriers to become America’s first female State Paleontologist, methodically cataloguing the ancient crinoids of New York State whilst pioneering the scientific understanding of the 380-million-year-old Gilboa forest. Her commitment to making paleontology accessible through public education and museum displays demonstrated that rigorous scientific research could serve society’s broader understanding of natural history.

Miss Goldring, thank you for joining us today. You’ve witnessed extraordinary changes in our understanding of prehistoric life since your time. Looking back, what drew you to those ancient forest stumps at Gilboa when so many of your colleagues were fascinated by dramatic dinosaur discoveries?

You must understand, those stumps were a proper mystery that had been teasing scientists for over fifty years when I took them on. The fellows at the Museum had been puzzling over these enormous petrified bases since the 1870s, calling them everything from “tree ferns” to “seed ferns” without any real evidence. What attracted me wasn’t their fame – goodness knows, they weren’t as thrilling to the press as those monstrous reptiles – but the sheer scientific challenge they presented. Here were the remains of Earth’s oldest known forest, and nobody could tell you what manner of trees they actually were.

The timing was crucial, you see. When New York City decided to flood the Gilboa valley for their reservoir in 1920, it became a race against time. We had to conduct what you might call “salvage geology” – rushing ahead of the steam shovels to preserve what we could before it all disappeared under water forever. There’s something rather fitting about studying ancient life whilst fighting against modern progress, don’t you think?

Your rigorous approach to the Devonian crinoids was groundbreaking – completing a massive project that several male predecessors had abandoned. Can you walk us through your methodology?

Oh, that project! Dr. Clarke handed me what amounted to decades of unfinished work – boxes of specimens, scattered notes, incomplete drawings – and suggested I “have a go at it.” The previous fellows, Hall, Clarke himself, Edwin Kirk, Charles White, they’d all started but never finished. I suspect they found the work rather tedious.

But you see, that’s where they misunderstood the nature of scientific work. Taxonomy isn’t glamorous, but it’s the foundation of everything else. I spent seven years methodically examining every specimen, cross-referencing every note, creating comprehensive descriptions. Out of 25 families, 60 genera, and 155 species I recorded, I identified 2 new families, 18 new genera, and 58 new species. The resulting monograph was 670 pages with 60 plates – each drawing executed by our museum artist George Barkentin.

Tell us about your technique for studying these ancient sea lilies. What tools and methods did you develop?

The crinoid work required absolute precision in measurement and classification. Each specimen had to be photographed, drawn to exact scale, measured in multiple dimensions – calyx height, arm length, stem diameter. I developed a standardised approach to describing the calyx plating patterns, arm structures, and stem characteristics that became the standard methodology.

But here’s what the official records don’t tell you: I kept detailed field notebooks where I recorded not just measurements but observations about preservation conditions, matrix composition, and associated fauna. I noticed that crinoids from certain limestone beds showed better preservation of delicate features, which told us about ancient sea floor conditions. I also developed techniques for preparing acid-etched specimens to reveal internal structures – rather risky work with the chemicals we had then, but it revealed morphological details invisible on weathered surfaces.

The key was understanding that each specimen was part of a larger ecological story. These weren’t just pretty fossils to catalogue – they were evidence of ancient marine ecosystems, current patterns, water depths, and environmental changes across millions of years.

Your work on the Gilboa forest challenged established thinking about early plant evolution. How did you determine that Eospermatopteris was actually a cladoxylopsid rather than a seed fern?

This is where careful fieldwork proved essential. The early researchers – Dawson, Hall, even my own colleagues initially – were making assumptions based on fragmentary evidence. They saw large stumps and assumed “tree ferns” or “seed ferns” because those fitted their expectations of what early forests should look like.

I approached it differently. I examined the internal anatomy of the stumps using thin sections – cutting the fossils razor-thin and examining them under microscope. The vascular bundle arrangement, the cellular structure, the growth patterns – none of it matched what you’d expect from true seed ferns. The stumps showed a central pith surrounded by a ring of vascular strands, quite unlike the solid wood core you’d find in gymnosperms.

More importantly, I studied the associated flora from the same beds. No genuine seed structures, no ovules, no pollen organs – nothing that would support the seed fern hypothesis. When we finally found the crown portions in 2007 – well after my time, of course – they vindicated my classification. Those finger-like branches covered in whorls of branchlets were exactly what I’d predicted for a cladoxylopsid.

You faced significant institutional challenges as a woman in science. You even resigned briefly in 1918 over salary issues. How did you overcome these barriers?

Let me be quite clear about this – the barriers weren’t just about politeness or social convention. They were about professional survival. In 1918, I was doing the same work as my male colleagues but earning substantially less. When I raised this with the administration, I was told that women didn’t need the same compensation because we didn’t have families to support. Absolute rot, of course.

I resigned on principle, but I also knew I had leverage. My crinoid work was nearly complete, and the Museum needed that project finished. More importantly, I’d established relationships with collectors and institutions across the state who valued my expertise. Dr. Cooper at the Smithsonian, Irving Reimann in Buffalo – they were sending me specimens to identify because they trusted my work.

The truth is, I never married partly by choice and partly because the demands of serious scientific work didn’t leave room for the domestic expectations placed on wives. I lived with my family in Slingerlands for 81 years, which gave me stability and support whilst maintaining my independence. My seven sisters and I created our own support network.

Your educational philosophy was quite progressive. Tell us about your “Handbook of Paleontology for Beginners and Amateurs.”

Ah, now that was a project close to my heart! The first volume appeared in 1929, revised in 1950. The scientific establishment thought I was wasting time writing for “amateurs,” but I knew better. Real scientific progress depends on public understanding and support.

The handbook taught people how fossils actually form, how to collect them properly, and how to understand the relationships between different life forms. I included detailed drawings, clear explanations of geological time, and practical collecting advice. I even encouraged readers to colour the formation charts with crayons or watercolours – imagine the horror of my more staid colleagues!

But here’s what I understood that many didn’t: every professional paleontologist started as an amateur. Every museum visitor who stops to read a fossil label is a potential scientist. The boy who collects trilobites in his back garden might become the researcher who solves the next great mystery of deep time.

Your museum exhibitions were legendary, particularly the Gilboa forest diorama. How did you approach public education through displays?

The Gilboa diorama was my masterpiece of public education. Working with Jules Henri Marchand and his sons, we created a full-scale reconstruction of Earth’s oldest forest. But this wasn’t mere artistic fancy – every detail was based on scientific evidence.

I had to work out what these ancient trees actually looked like from fragmentary remains. Using associated fossils and understanding Devonian plant evolution, I concluded that Eospermatopteris was transitional – still using spores but showing characteristics that would lead to seed production. My rendering showed straight trunks with bulbous root systems and soft, willowy foliage.

The exhibit included the sound of running water, rich colour schemes, and careful placement of actual fossil specimens within the recreated environment. Visitors could see, hear, and nearly smell this ancient world. The display drew international attention and remained a centrepiece of the Museum from 1924 to 1976.

But I also created outdoor exhibits – roadside displays near Gilboa itself where people could see the actual fossil stumps in their geological context. Education shouldn’t be confined to museum walls.

You conducted significant geological mapping work throughout New York State. How did this fieldwork inform your paleontological research?

Every summer, I was out in the field with my geological hammer and collecting bags. Mapping work gave me an intimate knowledge of New York’s rock formations that you simply cannot get from museum specimens.

Understanding the stratigraphic context – which rocks are older, how they formed, what environmental conditions they represent – is absolutely crucial for paleontological interpretation. When you find a crinoid colony preserved in limestone, you need to understand the depositional environment, the associated fauna, the regional geology. Was this a shallow reef? Deep marine basin? Storm deposit?

I mapped the entire Schoharie Valley, learning every outcrop, every formation boundary. This groundwork proved invaluable when interpreting the Gilboa fossils. I could place those ancient trees within their proper geological and environmental context – understanding that they grew in marshy lowlands near an ancient inland sea, subject to periodic flooding and sediment burial.

Looking back, do you have any regrets about paths not taken or mistakes in your scientific work?

Well, I must admit I was rather too confident about that “seed fern” interpretation initially. The concept of seed ferns as transitional forms was widely accepted in the 1920s, and it seemed to fit the evidence we had. But science progresses by correcting such errors, doesn’t it?

I also regret not travelling more widely. My trips to Gaspé and Nova Scotia with Dr. Clarke were immensely valuable, but I was rather too provincial, staying mostly within New York State. Paleontology benefits from comparative studies across different regions and formations.

Perhaps most significantly, I sometimes wonder if I was too accommodating to institutional limitations. When they questioned my salary, I should have demanded equality more forcefully from the start. When they suggested women couldn’t handle certain types of fieldwork, I should have challenged those assumptions more directly rather than proving myself through quiet competence.

What advice would you give to women entering STEM fields today?

First, master your technical skills completely. In my day, and I suspect still today, women must be twice as competent to receive half the recognition. Learn your methods, understand your equipment, know your literature better than anyone else in the room.

Second, don’t let anyone convince you that certain scientific questions are “unsuitable” for women. When I started, paleobotany was considered descriptive rather than theoretical – somehow less intellectually rigorous than vertebrate paleontology or experimental biology. Absolute nonsense. The questions I was asking about ancient ecosystems, plant evolution, and environmental change were every bit as complex and important as anything being studied in the prestigious university laboratories.

Third, remember that science serves society. Don’t let the pursuit of academic prestige distract you from the broader purpose of scientific work. My public education efforts were sometimes dismissed by colleagues as “popularisation,” but they created the next generation of scientists and ensured public support for research funding.

How do you view the evolution of paleontology since your time? What would surprise you most about modern methods?

The technological advances would astonish any paleontologist from my era! Electron microscopy, isotope analysis, radiometric dating, computer modelling – tools that would have solved so many puzzles we struggled with using only hand lenses and careful observation.

What particularly excites me is how modern climate research has vindicated the importance of paleobotanical work. When I was studying ancient plant communities, that research was considered purely descriptive. Now scientists understand that fossil plant assemblages are crucial for understanding past climate changes and predicting future environmental shifts. The Gilboa forest isn’t just a curiosity – it’s evidence of how ecosystems respond to major environmental transitions.

I’m also pleased to see that taxonomy – the careful, methodical work of classification and description – remains fundamental to paleontological research. All those hours spent measuring crinoid calyxes and describing morphological details weren’t wasted effort. They created the foundation that modern researchers still use.

Your career spanned both world wars and massive social changes. How did these broader historical events affect your scientific work?

The wars certainly affected museum operations. During the first war, we lost several younger staff members to military service, which increased responsibilities for those of us who remained. Resources became tighter, and there was pressure to demonstrate the practical value of scientific research.

But I found that major historical events often highlighted the importance of long-term perspective. When society is focused on immediate crises, paleontology offers something valuable – the understanding that Earth and life have survived previous catastrophes, that change is constant, that current problems are part of much larger patterns spanning millions of years.

The social changes – women gaining the vote, increasing educational opportunities – certainly made my career possible. But I must say, scientific institutions were often the last to embrace these changes, not the first. The Paleontological Society elected me president in 1949, but it took genuine pressure from members who valued scientific competence over social convention.

What do you think would be the most important discovery waiting to be made in your field?

The complete understanding of early terrestrial ecosystems! We’ve learned so much about individual species, but the relationships between plants, soils, climate, and the first land animals remain only partially understood.

I’d particularly love to know more about the transition from marine to terrestrial life during the Devonian. How did those first forests change atmospheric composition? How did root systems affect soil development and erosion patterns? What was the role of fungi in supporting these early plant communities?

And the Gilboa forest – we saved perhaps forty specimens, but there were probably thousands more lost to construction and flooding. Modern techniques applied to similar sites might reveal the full diversity of early forest ecosystems.

Finally, what would you want your legacy to be?

I hope to be remembered as someone who demonstrated that patient, disciplined work has its own form of brilliance. Not every scientific advance comes from dramatic discoveries or theoretical breakthroughs. Sometimes progress requires methodical attention to detail, careful observation, and the willingness to complete unglamorous but essential work.

I’d also want people to understand that science belongs to everyone, not just university professors. Some of my most important specimens came from amateur collectors, local quarry workers, and curious citizens who noticed something unusual in the rocks. Science advances when we combine institutional expertise with broad public engagement.

Most importantly, I hope I showed that women could succeed in science not by accepting limitations but by refusing to be limited. When they told me certain work was unsuitable for women, I proved them wrong through competence. When they suggested state museum work was less prestigious than university research, I demonstrated that public service could produce world-class science.

The questions I asked about ancient life, environmental change, and Earth’s deep history – those questions are more relevant today than they were in my time. That’s the true measure of scientific importance: not immediate recognition, but lasting relevance to humanity’s understanding of our place in natural history.

Letters and emails

Following our conversation with Winifred Goldring, we’ve received an overwhelming response from readers eager to explore her pioneering work in greater depth. We’ve selected five letters and emails from our growing international community who want to ask her more about her life, her scientific methods, and what she might say to those walking in her footsteps today.

Sophia Martinez (34, Climate Scientist, Montreal, Canada)

Miss Goldring, modern paleoclimatologists use isotope analysis and trace element chemistry to reconstruct ancient atmospheric CO₂ levels and temperatures. When you were studying those Devonian plant communities at Gilboa, what observable characteristics in the fossil specimens hinted at the climate conditions these early forests experienced? Could your morphological observations about leaf structure and growth patterns have told you anything about ancient rainfall or seasonal patterns that we’re now confirming through geochemical methods?

Miss Martinez, what a fascinating question! You know, we didn’t have your fancy chemical analysis in my day, but a trained eye could read quite a lot from the fossils themselves if you knew what to look for.

When I examined those Gilboa specimens, the morphological evidence for climate was written right into the plant structure. The Eospermatopteris stumps showed remarkably thick, bulbous root systems – what we called “onion-base” structures – which suggested these trees were growing in waterlogged, swampy conditions. But here’s what was particularly telling: the associated flora included numerous spore-bearing plants with delicate, fern-like fronds that simply wouldn’t survive in arid conditions.

The leaf impressions we found – and we did find some, though precious few – showed characteristics I’d associate with high humidity environments. Large, undivided fronds with prominent venation patterns, rather like what you’d see in a modern tropical fern house. No waxy cuticles or reduced leaf surfaces that would indicate water stress.

But the real climate indicator was the preservation itself, my dear. Those beautiful pyrite and marcasite replacements in the plant tissues told me we were dealing with rapid burial in oxygen-poor, waterlogged sediments. The alternating limestone and shale beds suggested periodic marine incursions – rather like the Florida Everglades meeting the sea, if you can picture it.

Most intriguingly, the growth rings in some specimens – yes, even those ancient plants showed seasonal patterns – indicated regular wet and dry cycles. Not the extreme seasonal variation you’d expect in a temperate climate, but the sort of gentle alternation between wetter and drier periods you might find in a subtropical coastal plain.

I suspected we were looking at a warm, humid climate with seasonal rainfall patterns, probably rather like the modern Gulf Coast of the southern states. Of course, I couldn’t quantify the temperature or atmospheric composition as you clever modern folks can, but the botanical evidence was quite clear about the general environmental conditions. Rather satisfying to know that your geochemical methods have confirmed what careful morphological observation suggested all along, don’t you think?

Viktor Kuznetsov (28, Museum Curator, Prague, Czech Republic)

What if the New York City reservoir project had been delayed by twenty years, giving you more time for excavation at Gilboa? Do you think having access to the complete forest floor – rather than just the salvaged specimens – would have fundamentally changed our understanding of early terrestrial ecosystems? I’m curious whether you believe the time pressure actually focused your research in productive ways, or if it limited discoveries that might have revolutionised paleobotany even earlier.

Mr. Kuznetsov, that’s a question I’ve pondered many times over the years, particularly during those frantic weeks when we could hear the steam shovels getting closer each day.

You know, there’s something to be said for working under pressure. When you’ve got limited time, you focus on what’s truly essential. We couldn’t afford to dawdle over every interesting specimen – we had to make quick decisions about what was most scientifically valuable. That urgency forced me to develop a keen eye for recognizing the most significant finds almost instantly.

But oh, what we lost! I estimate we salvaged perhaps one percent of what was actually there. The construction crews were finding stumps every few yards across that entire valley floor – hundreds, possibly thousands of specimens that went straight into the concrete mixers for the dam. Each one could have told us something about the spatial distribution of that ancient forest, the diversity of species, the ecological relationships.

Had we possessed twenty more years, I believe we might have mapped the entire forest structure. Think of it – we could have understood how these early trees were distributed across the landscape, whether they formed dense groves or scattered woodlands, how they related to the ancient stream channels and marine incursions. We might have found the complete canopy portions decades earlier than your modern colleagues finally did.

More importantly, we could have studied the associated fauna more thoroughly. We found fragments of early arthropods, primitive fish remains, even what appeared to be amphibian traces, but there wasn’t time for proper excavation. A complete ecological picture of Earth’s first forest ecosystem – that would have been revolutionary indeed.

But here’s the curious thing: that time pressure also gave our work a sense of urgency and importance that might have been lacking otherwise. The Museum administration, the press, even the general public understood we were racing to save irreplaceable scientific treasures. That drama helped secure funding and attention that might have been harder to obtain for a leisurely, decades-long study.

Sometimes I wonder if having all that time might have made us too comfortable, too willing to leave things for “next season’s fieldwork.” The pressure certainly concentrated our efforts wonderfully, even as it limited our scope.

Amara Jallo (31, Geological Survey Officer, Lagos, Nigeria)

You mentioned that some of your most important specimens came from amateur collectors and quarry workers rather than formal expeditions. How did you build those relationships with local communities, and what convinced working-class people to trust their discoveries to a woman scientist when the academic establishment was still questioning your authority? I ask because in our geological surveys across West Africa, we’re finding that community engagement remains crucial for significant discoveries.

Miss Jallo, now that’s a question that goes straight to the heart of how real scientific work gets done! You see, those quarry workers and farmers weren’t just “sources” for specimens – they were genuine collaborators, though the academic establishment would never have called them that.

The trick was treating them as experts in their own right, because they were! A man who’s been blasting limestone for twenty years knows every inch of his quarry, every unusual formation, every pocket where interesting things turn up. When I visited the quarries around Albany and the Helderberg escarpment, I didn’t arrive with my university credentials and expect deference. I came with genuine curiosity about what they’d observed.

I’d spend time watching them work, asking questions about the rock layers, listening to their stories about unusual finds. Many of these fellows had been collecting curious stones for years – keeping them on mantelpieces or in cigar boxes – without knowing their scientific significance. When I showed genuine interest in their observations and explained what their discoveries meant, they became tremendously enthusiastic collaborators.

Here’s what the academic fellows didn’t understand: working people respected competence and practical knowledge above social position. When I could identify a fossil on sight, explain how it formed, and describe what it told us about ancient environments, that earned their respect far more than any university degree would have.

I also made sure they benefited from our relationship. I’d write letters to quarry supervisors explaining the scientific importance of preserving unusual specimens. Sometimes I could arrange for the Museum to purchase particularly valuable finds, putting a bit of extra money in a worker’s pocket. I always made sure they received proper credit when their discoveries were published or displayed.

The gender question was interesting, actually. Many of these men had wives and daughters at home, and they weren’t shocked by the idea of a woman having expertise. In fact, some seemed more comfortable talking with me than they might have been with a pompous male professor. I wasn’t threatening their position or acting superior – I was genuinely interested in learning from their experience.

But I won’t pretend it was always easy. There were certainly men who dismissed me initially, or who thought my interest in rocks was just a peculiar female hobby. The key was demonstrating knowledge quickly and practically. Once they saw I could tell good limestone from poor, identify valuable fossils, and explain geological formations, professional respect usually followed.

Your work in West Africa sounds tremendously important, Miss Jallo. I suspect you understand that the most significant discoveries often come from local knowledge combined with scientific training – a partnership that benefits everyone involved.

Gabriel Fonseca (26, Evolutionary Biologist, São Paulo, Brazil)

You worked during a period when paleobotany was dismissed as merely ‘descriptive’ science, yet your morphological classifications proved foundational for understanding plant evolution. Today, we have molecular phylogenetics and genetic sequencing that can trace evolutionary relationships directly through DNA. Do you ever feel vindicated that your careful morphological work predicted evolutionary relationships that molecular evidence later confirmed? Or do you think there are aspects of plant evolution that only fossil morphology can reveal, even in our molecular age?

Mr. Fonseca, you’ve touched upon something that gave me considerable satisfaction during those years when my colleagues dismissed morphological work as mere “stamp collecting”!

You see, the theoretical fellows were so eager to embrace the new experimental biology – genetics, biochemistry, cellular studies – that they rather foolishly assumed morphology had nothing important to tell us. They wanted dramatic laboratory results and mathematical models, not careful observations of fossil plant structures. But morphology was never just description, you understand – it was reading the evolutionary story written in stone.

When I classified those Devonian crinoids and worked out the relationships between different species, I wasn’t simply cataloguing pretty specimens. I was tracing evolutionary lineages, understanding how marine ecosystems developed over millions of years. The arm branching patterns, the calyx plate arrangements, the stem structures – these weren’t arbitrary characteristics but evolutionary innovations that told us how these creatures adapted to changing environments.

My work on Eospermatopteris was particularly satisfying in this regard. When I concluded it was a cladoxylopsid rather than a seed fern, I was making predictions about plant evolutionary relationships based purely on anatomical evidence. The vascular bundle patterns, the growth forms, the reproductive structures – all of this pointed to a specific place in the evolutionary tree, decades before your molecular biologists had any way to confirm such relationships.

But here’s what I learned that your modern DNA work can’t replace: morphology reveals the ecological context of evolution. When I examined those ancient plant tissues, I could see how they were adapted to specific environmental conditions – waterlogged soils, seasonal flooding, particular light regimes. Molecular evidence might tell you that two species are related, but only morphological analysis explains why they evolved the way they did.

The fossil record also captures evolutionary experiments that failed – entire lineages that tried different approaches to terrestrial life and didn’t survive. Your molecular techniques can only study what’s still alive today. But I could examine the complete range of early plant strategies, including the dead ends and false starts that shaped the history of life on land.

I must say, I’m rather pleased that modern paleobotanists are finding that careful morphological work remains essential, even with all your fancy molecular tools. You can sequence DNA from living plants all you like, but if you want to understand how terrestrial ecosystems actually evolved, you still need someone who can read the story preserved in ancient plant tissues. Some questions can only be answered by examining the fossil evidence with a trained eye and a proper understanding of plant anatomy.

Rather vindicating, wouldn’t you say?

Keiko Nakamura (29, Science Education Researcher, Tokyo, Japan)

Your philosophy of making science accessible to the public through exhibits and handbooks was quite revolutionary for your time. Looking at how scientific communication has evolved – with social media, virtual reality museum experiences, and global connectivity – do you think there are aspects of hands-on, physical engagement with specimens that we risk losing? What would you say to modern educators who argue that digital tools can replace direct interaction with fossils and geological materials?

Miss Nakamura, you’ve raised something I feel quite strongly about. There’s an irreplaceable quality to handling actual specimens that no amount of technological wizardry can duplicate, I’m afraid.

When a child picks up a 400-million-year-old crinoid stem and feels its weight, examines the perfect five-fold symmetry of the segments, runs their finger along the central canal where the creature’s soft tissues once passed – that’s a direct connection to deep time that simply cannot be replicated on a screen, no matter how clever the programming.

I spent considerable effort in my exhibits ensuring visitors could touch selected specimens. The Gilboa diorama included handling stations where people could examine actual fossil bark, feel the texture of ancient wood, compare the weight of petrified specimens to modern plant materials. That tactile experience taught lessons about fossilization, preservation, and geological time that pure visual displays never could.

But it goes deeper than simple touch, you see. When you’re working with real specimens, you notice things – subtle variations in colour that indicate different preservation conditions, tiny associated fossils that reveal ancient ecological relationships, fracture patterns that tell you about post-depositional history. I discovered several new species simply by noticing details that weren’t visible in photographs or drawings but became obvious when examining specimens under proper lighting with a hand lens.

My “Handbook of Paleontology” emphasized this hands-on approach deliberately. I wanted amateur collectors to understand that real scientific observation required direct engagement with specimens. You learn to recognize limestone versus shale, to distinguish original material from replacement minerals, to spot the subtle differences between similar species – but only through repeated handling of actual fossils.

However, I must say your modern digital tools do offer possibilities I couldn’t have imagined. If they allow people in remote locations to examine high-quality images of important specimens, or if they help preserve fragile materials that might otherwise deteriorate, then they serve genuine scientific purposes.

The danger lies in substitution rather than supplementation. A digital fossil cannot teach you about weight, hardness, crystal structure, or the dozens of subtle characteristics that only emerge through direct examination. More importantly, working with real specimens teaches patience, careful observation, and respect for the materials we study – qualities that are rather essential for any serious naturalist.

I’d tell modern educators that digital tools should open doors to specimen-based learning, not replace it. Use your screens to excite interest, to provide context, to connect distant learners – but always with the goal of eventually bringing people face-to-face with the actual evidence of Earth’s history. That’s where the real learning happens, Miss Nakamura.

Reflection

Winifred Goldring passed away on 30th January 1971 at the age of 82, having witnessed eight decades of scientific revolution whilst maintaining her conviction that careful observation and public engagement remained the bedrock of meaningful research. Her voice today reveals nuances often missing from official histories – the pragmatic strategies she used to navigate institutional barriers, her genuine respect for working-class collaborators, and her unapologetic pride in choosing descriptive science over fashionable theoretical work.

The historical record captures her professional achievements but often overlooks the daily realities of being the sole woman in scientific meetings, the financial pressures that nearly ended her career in 1918, or her strategic use of public education to secure institutional support. Her responses suggest someone more politically astute and personally resilient than formal biographies typically acknowledge.

What emerges most powerfully is her prescient understanding that paleobotany would prove crucial for comprehending environmental change – a vindication that modern climate researchers confirm daily. Her insistence that museum work could produce world-class science challenges persistent hierarchies between public institutions and elite universities. Her commitment to hands-on learning resonates urgently in our digital age, where virtual experiences increasingly substitute for direct engagement with natural materials.

Perhaps most significantly, Goldring’s story illuminates how scientific progress depends not just on individual brilliance but on networks of collaboration spanning social classes and institutional boundaries. Her legacy lives in every fossil discovered by amateur collectors, every museum exhibit that sparks curiosity, and every researcher who understands that asking the right questions about ancient life requires both rigorous methodology and deep respect for the Earth’s enduring mysteries.

The questions she asked about deep time remain as vital today as they were a century ago.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview represents a dramatised reconstruction based on extensive historical research into Winifred Goldring’s life, scientific work, and documented perspectives. While grounded in factual sources including her published papers, museum records, and contemporary accounts, the dialogue and specific responses are imaginative interpretations designed to bring her voice and expertise to modern readers. Any opinions expressed reflect our interpretation of her documented views and the historical context of her era, not verbatim quotes from primary sources.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved. | 🌐 Translate

Leave a comment