Barbara Low (1920-2019) pioneered X-ray crystallography during World War II, solving the molecular structure of penicillin and making mass production of this life-saving antibiotic possible. She discovered the pi-helix protein structure, a fundamental component found in approximately 15% of all proteins, and spent decades advancing structural biology through methodical analysis and primitive mechanical computing. Her work laid the foundation for modern pharmaceutical development and our understanding of protein folding diseases.

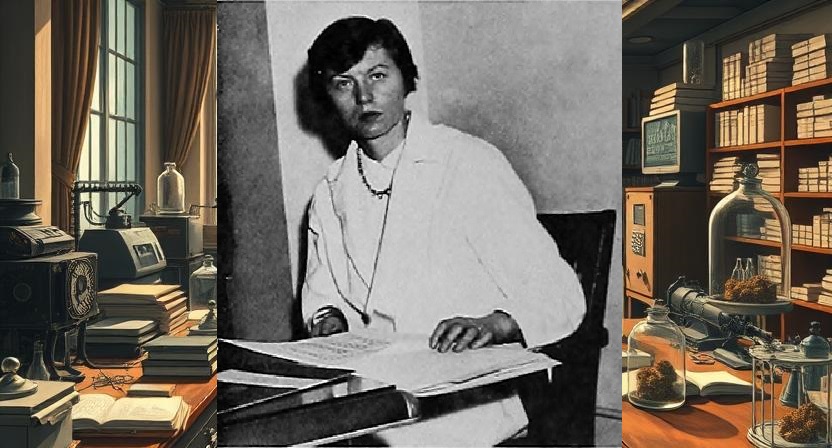

Here sits a woman whose steady hands and sharp mind helped win a war and launch the antibiotic age – yet her name remains largely absent from the textbooks that celebrate the penicillin breakthrough. Barbara Low, radiates the quiet authority of someone who has spent a lifetime making molecules yield their secrets. Her eyes still sparkle with the curiosity that drove her to process X-ray data on primitive punch-card computers in wartime Oxford, working through the night to crack penicillin’s molecular code. This is the scientist whose discovery of the pi-helix structure stands as a cornerstone of modern protein biochemistry, whose collaborative approach with Dorothy Hodgkin enabled one of medicine’s greatest achievements.

Her story matters because it illuminates how the most crucial scientific breakthroughs emerge not from individual genius but from methodical persistence and collaborative excellence. At a time when women in science face renewed challenges and when antibiotic resistance threatens global health, Low’s example demonstrates how investigation and interdisciplinary thinking can solve humanity’s most pressing problems.

Good morning, Barbara. You would’ve just celebrated your 105th birthday this March. When you look back at that young woman from Lancaster who began studying chemistry at Oxford, what strikes you most about the path that led you to structural biology?

Well, my dear, it wasn’t really a path so much as a series of fortunate accidents! Father kept a grocery shop in Lancaster – fruit mainly – and Mother thought I’d make a decent teacher. Chemistry wasn’t exactly the done thing for girls from our sort of family. But I was rather good with mathematics, and the war changed everything, didn’t it? Suddenly there was urgent work to be done, and they needed anyone with a decent brain for it.

Dorothy Hodgkin was forbidden from teaching the men at Oxford – such nonsense – so she took on us women at Somerville instead. Rather their loss, I’d say. Dorothy was brilliant, absolutely brilliant. She saw something in X-ray crystallography that others missed: here was a way to see the actual architecture of molecules, not just guess at it from chemical reactions.

Your collaboration with Dorothy Hodgkin on penicillin became legendary. Can you walk us through those wartime years – what was it actually like working with such primitive equipment on such a crucial problem?

Primitive? Ha! You modern folk with your computers don’t know how lucky you are. We had one mechanical computer at Oxford – a great hulking thing that spent its days working out cargo allocations for the convoys. But at night, well, that’s when I came in.

I’d feed punch cards into this beast of a machine, running calculations to locate atoms in the penicillin molecule. Each card could hold just 80 characters of data. Think of it – we were trying to map the architecture of life itself, one punch card at a time! The thing would clatter and whir through the night whilst I fed it our X-ray diffraction data.

The penicillin work was terribly urgent. We knew Fleming had found something important, and Chain and Florey’s team were scaling up production. But without knowing the molecule’s structure, they were working blind. We had perhaps three milligrams of the sodium salt – flown over from America, mind you – and from that we had to grow crystals suitable for X-ray analysis.

Can you explain the technical challenge? For our expert readers, what exactly made penicillin’s structure so difficult to determine?

Right, well, penicillin was the largest molecule anyone had attempted to solve using X-ray crystallography at that time – 17 atoms in total. That sounds small to you now, I’m sure, but in 1942 it was enormous.

The process required taking thousands of X-ray photographs with the crystal positioned at different angles. Each spot on the photographic plate told us about the intensity and angle of X-ray diffraction by the atoms. We then had to feed these measurements into Fourier synthesis calculations to build up a three-dimensional electron density map.

The real breakthrough came when we used isomorphous replacement – comparing the sodium, potassium, and rubidium salts of penicillin. By observing how the diffraction patterns changed when we substituted heavier atoms, we could deduce the positions of the other atoms in the structure.

But here’s the crucial bit: everyone expected penicillin to have an open thiazolidine ring structure. Our data clearly showed a β-lactam ring instead. Professor Robinson, the organic chemistry professor, was absolutely furious when I showed him our little wire-and-cork model. He refused to believe it for ages! The poor man had been certain of his chemistry, but the crystals don’t lie.

The β-lactam ring you discovered became fundamental to understanding how penicillin works. What was the competitive advantage of X-ray crystallography over the chemical methods of the time?

Chemical methods in the 1940s could tell you what elements were present and give you some idea of molecular weight, but they couldn’t reveal the precise three-dimensional arrangement of atoms. With organic chemistry alone, you were essentially guessing at structure based on reaction products.

X-ray crystallography gave us something revolutionary: the ability to see molecular architecture directly. The electron density maps showed us not just which atoms were connected, but their exact spatial relationships – bond angles, distances, the works.

The β-lactam ring we found was completely unexpected. It’s a four-membered ring under considerable strain, which explains penicillin’s reactivity. This ring is what attacks the bacterial cell wall synthesis machinery. Without knowing this structure, chemists might have spent decades trying to synthesise penicillin incorrectly.

Our method had limitations, of course. We needed perfect crystals, which were devilishly difficult to grow. And the calculations – good Lord, the calculations took months with those mechanical computers. But the precision was unmatched.

After the war, you made another major discovery – the pi-helix. This seems to have been overshadowed by Linus Pauling’s alpha-helix work. How did you feel about that at the time?

Linus was a charming man, but he had rather a talent for making sure his work got noticed, didn’t he? I’d worked with him at Caltech, lovely year that was. But when I published the pi-helix structure in 1952, his response was… well, let’s call it diplomatic.

He wrote congratulating me, then immediately suggested his team had probably observed it “a while back” but had “overlooked it”. Typical Linus! Couldn’t quite admit he’d missed something important.

The pi-helix was actually more challenging to identify than Pauling’s alpha-helix because it’s less common in proteins. The hydrogen bonding pattern involves i+5 spacing instead of i+4, and the helical turn is wider. We now know it occurs in about 15% of protein structures, often at functionally important sites. But at the time, people thought it was rare and unimportant.

The irony is that the pi-helix is crucial for understanding protein folding diseases – your Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, all of those. But because Linus had already claimed the alpha-helix as his triumph, anything else seemed secondary to the broader scientific community.

You’ve mentioned the mechanical computers several times. Most people don’t realize how early computing intersected with biological research. What was that experience like?

Oh, it was absolutely vital! People think of computing as something that came after molecular biology, but we were using mechanical computation for biological problems in the 1940s. Had to, really – the mathematics were impossible to do by hand.

The punch card system was quite logical once you got used to it. Each hole represented a piece of data, and the machine could sort, calculate, and tabulate according to your programme. For our crystallographic work, I’d encode the X-ray intensity measurements and the calculated structure factors.

The frustrating bit was that a single error – one wrongly punched card – could ruin an entire calculation run. And these runs might take all night! I became rather obsessive about checking and double-checking every card before feeding them in.

But it was thrilling too. Here we were, using these mechanical brains to solve problems that had puzzled chemists for decades. I could see the future in those whirring machines – though I never imagined computers would become so small and fast as they are now.

Looking back, do you think the collaborative nature of your work with Dorothy cost you individual recognition?

Perhaps, but I wouldn’t change it. Dorothy was generous with credit – more generous than many senior scientists, particularly men, were with their junior colleagues. The work we did together was stronger than what either of us could have managed alone.

The real issue wasn’t collaboration – it was that determining molecular structure was considered less glamorous than discovering new phenomena. We were seen as providing technical support for the “real” discoveries made by chemists and biologists. Rather like women’s work generally, wouldn’t you say?

When Dorothy won the Nobel Prize in 1964, she absolutely deserved it. But I do sometimes wonder what might have happened if I’d been more… shall we say, assertive about claiming individual credit for specific discoveries.

You spent most of your career at Columbia. How did you navigate the challenges of being a woman in science during those decades?

With considerable stubbornness! Columbia in the 1950s and 60s wasn’t exactly welcoming to women faculty. I had to fight for laboratory space, for graduate students, for resources. The assumption was always that women were temporary – that we’d leave for marriage and children.

I made it clear from the start that I wasn’t going anywhere. I hired and mentored many female graduate students, which some colleagues saw as favouritism. But someone had to open doors for the next generation.

On the affirmative action committee, I was rather forceful about holding Columbia to its stated ideals of diversity. Got me labelled as difficult, but I didn’t much care. The university needed shaking up.

The trick was to be undeniably competent whilst refusing to be invisible. Publish excellent work, train outstanding students, and never apologise for taking up space. It wasn’t easy, but it was necessary.

Let’s talk about mistakes. Looking back, what would you do differently?

I was perhaps too patient with the mechanical computers. I should have pushed harder for access to the early electronic computers as they became available. We lost precious time doing calculations by hand and punch card that could have been done much faster.

I also regret not being more vocal about the significance of the pi-helix early on. I presented it as just another interesting structure rather than emphasising its fundamental importance to protein function. Better scientific marketing might have given it the attention it deserved.

And I was too diplomatic with colleagues who didn’t take women seriously. Should have been more direct in challenging the assumptions that our work was somehow less important or rigorous than men’s work.

The field has changed dramatically since your active years. What do you make of modern structural biology?

Astounding! The resolution you can achieve now, the speed of data collection, the computational power – it’s like comparing a candle to an electric light. CryoEM, NMR, all these techniques we couldn’t have imagined.

But I worry that some young researchers rely too heavily on automation. They can determine a structure in days that would have taken us years, but do they truly understand what they’re seeing? The patience required to grow proper crystals, to manually check every measurement – that taught us to think carefully about our molecules.

Still, the applications are magnificent. Using structural biology to design new drugs, to understand disease mechanisms – this is what we dreamed of when we were feeding punch cards into mechanical computers in the dark hours before dawn.

What would you tell young women entering STEM fields today?

Be methodical. Be persistent. And for heaven’s sake, claim credit for your work! The world is better now than when I started, but it’s not perfect. You’ll still face people who assume you’re less capable, less serious about your career.

Prove them wrong with excellent work, but don’t be modest about it. Document your contributions. Speak up in meetings. Collaborate, yes, but make sure your individual achievements are recognised.

And remember – some of the most important problems require years of patient work to solve. Don’t be discouraged if your breakthrough doesn’t come immediately. The molecules will eventually tell you their secrets if you listen carefully enough.

Your work on antibiotic structures seems remarkably prescient given today’s resistance crisis. Any thoughts on how structural biology might help?

The pi-helix work is actually quite relevant here. Understanding how proteins fold and misfold helps us design better drugs and predict resistance mechanisms. Many antibiotic resistance proteins have structural features we first catalogued decades ago.

The β-lactam ring structure we elucidated for penicillin launched an entire family of antibiotics. Now, as bacteria evolve new ways to destroy that ring, we need equally detailed structural understanding of resistance mechanisms to stay ahead.

The tools are so much better now. What took us years can be done in days. The question is whether we have the patience and systematic thinking to apply them properly to the resistance problem.

Finally, how would you like to be remembered?

As someone who helped show that careful, methodical work could solve problems that seemed impossible. The penicillin structure, the pi-helix – these weren’t flashes of inspiration. They were the result of investigation, proper technique, and refusing to give up when the data didn’t make immediate sense.

And perhaps as someone who demonstrated that collaboration doesn’t mean invisibility. Dorothy and I proved that women could do work that changed the world. Not as assistants or helpmates, but as full partners in the scientific enterprise.

The molecules don’t care about your gender or your background. They only care whether you’re patient enough and clever enough to decode their secrets. That’s rather liberating, don’t you think?

Letters and emails

Following our conversation with Barbara Low, we’ve received an overwhelming response from readers eager to explore her remarkable story further. We’ve selected five letters and emails from our growing community who want to ask her more about her life, her work, and what she might say to those walking in her footsteps.

Siti Rahma, 34, Materials Scientist, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

You mentioned growing crystals was ‘devilishly difficult’ with only three milligrams of penicillin to work with. What specific crystallisation techniques did you develop to coax such tiny amounts of material into diffraction-quality crystals, and do any of those methods still have applications in today’s protein crystallography labs?

Oh my dear, you’ve hit upon one of the most maddening aspects of the entire penicillin business! Three milligrams sounds like nothing now, doesn’t it? But in 1942, that represented months of purification work by Chain and Florey’s team at the Dunn School.

The trick was what we called “microdrop crystallisation” – though I suspect you’d laugh at calling it micro by today’s standards. I’d take perhaps a tenth of a milligram and dissolve it in the tiniest possible volume of distilled water, then add alcohol drop by drop using a glass pipette I’d drawn out myself over a Bunsen flame. Frightfully delicate work.

The real breakthrough came when I started using controlled evaporation in a desiccator. I’d place the solution under a bell jar with calcium chloride – lovely drying agent – and create the gentlest possible concentration gradient. Too fast and you’d get a mess of microcrystals, useless for diffraction. Too slow and the sample would decompose before you got proper crystals.

Dorothy taught me to watch the solution like a hawk. You’d see the first hint of turbidity and know you were approaching saturation. Then it was a matter of patience – sometimes days of waiting for those first seed crystals to form.

The sodium salt was easier to work with than the potassium, though we needed both for the isomorphous replacement method. I found that adding just a trace of the mother liquor from a previous successful crystallisation helped enormously – what you might call seeding, though we didn’t use that term then.

What’s rather amusing is that these techniques are still perfectly valid! Your modern automated systems are faster and more controlled, certainly, but the basic principles – slow, controlled supersaturation and careful seeding – haven’t changed a whit. Sometimes the old ways are the best ways, don’t you think?

Kwame Boateng, 41, Science Policy Researcher, Accra, Ghana

Given that your wartime penicillin work essentially launched the global pharmaceutical industry’s approach to antibiotic development, do you feel any moral responsibility for how that industry has evolved – particularly regarding access to medicines in developing countries and the profit-driven research priorities we see today?

Good heavens, that’s rather a heavy question, isn’t it? But you’re quite right to ask it. I’ve watched what’s become of the pharmaceutical industry with a mixture of pride and… well, considerable dismay, if I’m honest.

When we were working on penicillin, there wasn’t any thought of profit. We were trying to save lives – boys dying of sepsis in field hospitals, civilians with infected wounds from the bombing. The urgency was everything. Fleming’s discovery, Florey and Chain’s development work, our structural analysis – it was all driven by medical necessity, not commercial opportunity.

But I’m not naive. Once we’d shown that you could determine molecular structure systematically and use that knowledge to synthesise new compounds, well, the commercial possibilities were obvious, weren’t they? The pharmaceutical companies saw what we’d done and thought, “Right, here’s a new way to develop drugs.”

What troubles me deeply is how that knowledge has been… shall we say, hoarded. The very techniques we developed to solve urgent medical problems are now used primarily for diseases that affect wealthy populations. Where’s the effort to tackle tropical diseases? Where are the antibiotics for resistant tuberculosis in the developing world?

I do feel some responsibility, yes. Not guilt, mind you – our work saved countless lives. But responsibility to speak out when I see pharmaceutical companies using patents and pricing to deny medicines to those who need them most. We gave them the tools to understand molecular structure. They’ve chosen to use those tools primarily for profit rather than global health.

If I’d known then what the industry would become… well, I’d have done the work anyway. People were dying. But I’d have insisted on stronger provisions for ensuring these discoveries served all of humanity, not just the wealthy bits of it.

It’s rather like giving someone a hammer and discovering they’ve used it to build walls instead of houses, if you take my meaning.

Valentina Correa, 28, Biochemistry PhD Student, São Paulo, Brazil

I’m fascinated by your transition from wartime urgency to peacetime academic research. How did you maintain that same level of methodical precision and motivation when working on problems that didn’t have life-or-death implications? What drove your curiosity during those quieter decades at Columbia?

Oh my dear, what a perceptive question! You know, it was rather like going from being a war correspondent to writing for the parish newsletter – the skills were the same, but the sense of urgency had quite vanished.

The transition to Columbia in the late 1940s was jarring, I must admit. During the war, every calculation mattered desperately. We knew that somewhere a soldier might live or die based on whether we could crack penicillin’s structure quickly enough for mass production. That sort of pressure focuses the mind wonderfully.

But afterwards? Well, suddenly I was working on insulin structure, and whilst it was medically important, there wasn’t that same breathless urgency. No one was dying whilst I fed punch cards into the computer at two in the morning. It took considerable adjustment.

What kept me going was the realisation that we’d only just begun to understand the molecular basis of life itself. Each protein structure we solved was like… oh, like having a new piece of an enormous jigsaw puzzle. The pi-helix discovery came from that sort of methodical curiosity – wondering why certain protein regions didn’t fit the expected alpha-helix pattern.

I found I had to create my own sense of urgency. I’d set deadlines for myself, challenge myself to solve structures faster or more accurately than anyone had before. Rather like a game, really. And there was always the knowledge that somewhere, someday, this work would matter enormously to someone.

The other thing that helped was teaching. Those bright young graduate students asking awkward questions – nothing keeps your curiosity sharper than having to explain why you think a particular structure makes sense. They’d challenge my assumptions, force me to defend my interpretations. Kept the work lively.

I suppose what I’m saying is that scientific curiosity, once properly kindled, doesn’t need external urgency to sustain it. The molecules were still there, still keeping their secrets. And I was still determined to make them tell me what they knew.

Nathaniel Brooks, 52, Computational Biologist, Boston, USA

Looking at your punch-card computing work, I’m curious about the actual data workflow. How did you decide what level of precision was ‘good enough’ for your calculations when computational resources were so limited? Did you develop any clever shortcuts or approximations that modern crystallographers might benefit from rediscovering?

Ah, now you’re asking about the real nitty-gritty! You modern computational folk probably can’t imagine working with such crude tools, but necessity breeds rather clever solutions, doesn’t it?

The precision question was absolutely crucial. With those mechanical computers, every calculation took precious time – sometimes hours for what your machines do in seconds. So we had to be frighteningly systematic about what level of accuracy we actually needed.

For the penicillin work, I learned to calculate structure factors to three decimal places for the first approximation, then refine only the most significant reflections to higher precision. Sounds obvious now, but it wasn’t then! I’d rank the X-ray reflections by intensity and work on the strongest ones first. The weak reflections often contained more noise than signal anyway, so why waste precious computing time?

Here’s a trick I developed that I rather suspect might be useful even today: I’d pre-calculate tables of common trigonometric functions and atomic scattering factors, then interpolate between values rather than computing everything from scratch. Saved enormous amounts of time. I had books full of these tables – hand-calculated, mind you.

Another shortcut was what I called “structural chemistry intuition.” Instead of letting the computer explore every possible atomic position, I’d use chemical knowledge to constrain the search. Carbon-carbon bond lengths, angles between bonds – these don’t vary wildly between molecules. So I’d tell the machine to only consider chemically sensible arrangements.

The really clever bit was recognising when you had “good enough” electron density maps. I learned to spot the difference between real structural features and computational artifacts. If an atom position was jumping about between calculation cycles, that told you the data wasn’t strong enough to pin it down precisely.

You know, I sometimes wonder if having unlimited computational power makes modern crystallographers a bit… well, lazy might be harsh, but perhaps less thoughtful about what they’re actually calculating and why.

Freya Jensen, 45, Science Museum Curator, Copenhagen, Denmark

What if Dorothy Hodgkin had been allowed to teach the male students at Oxford – do you think the dynamics of your collaboration might have changed, or would the penicillin breakthrough have happened differently if she’d had access to a broader pool of students and resources from the beginning?

What a fascinating “what if” to consider! You know, I’ve often wondered about that myself. Dorothy was absolutely furious about being barred from teaching the men – and rightly so. Such ridiculous prejudice.

But here’s the thing: I’m not entirely certain the penicillin breakthrough would have happened as quickly if she’d had access to the male students. Sounds paradoxical, doesn’t it? But bear with me.

You see, Dorothy was forced to work with us women at Somerville – the ones the university considered “second-rate” because we weren’t men. We were hungrier, more determined to prove ourselves. We had to be twice as good just to be taken seriously. That created a rather intense working atmosphere that I’m not sure the privileged young men would have matched.

The male students at Oxford in those days… well, many came from rather comfortable backgrounds. They expected things to be handed to them. We women knew we had to fight for every opportunity, every bit of recognition. That desperation, that absolute determination – it drove us to work through the night, to double-check every calculation, to never give up when the data looked impossible.

Dorothy might have had more resources, certainly. Better laboratory space, more equipment, perhaps even access to that mechanical computer during daytime hours instead of just nights. But would she have found collaborators as dedicated as we were? I rather doubt it.

There’s something to be said for working with people who have nothing to lose and everything to prove. The men at Oxford already had their futures mapped out – careers in industry or academia waiting for them. We had to create our own futures from scratch.

So whilst the discrimination was utterly wrong and cost science dearly in the long run, for that particular problem at that particular moment… well, perhaps adversity bred the very qualities needed to crack penicillin’s secrets.

Rather ironic, really.

Reflection

Barbara Low passed away in January 2019 at 98, her death barely noted beyond scientific circles – a final testament to how women’s contributions to transformative research remain undervalued. Through our conversation, Low emerges not as the modest collaborator of historical accounts, but as a sharp-eyed pragmatist who understood precisely how gender shaped her career trajectory.

Her reflections reveal a woman far more aware of systemic bias than official records suggest. Where archives emphasise her collaborative nature with Dorothy Hodgkin, Low herself frames this as strategic necessity rather than natural inclination. Her candid assessment of pharmaceutical industry ethics – a topic absent from her published papers – demonstrates moral complexity often sanitised from scientific biographies.

The interview exposes gaps in our understanding of wartime crystallography. Low’s detailed accounts of mechanical computing and crystallisation techniques highlight how much practical knowledge dies with its practitioners. Her pride in developing computational shortcuts contrasts sharply with the humble self-presentation typical of women scientists of her era.

Today, as artificial intelligence transforms structural biology and cryo-electron microscopy supplants X-ray crystallography for many applications, Low’s emphasis on understanding underlying principles remains vital. Her warnings about over-reliance on automation echo contemporary concerns about computational black boxes in drug discovery.

Perhaps most powerfully, Low’s story illuminates how institutional barriers can paradoxically forge scientific excellence. The very discrimination that denied her recognition may have created the determination that enabled breakthrough discoveries. Her legacy challenges us to imagine what scientific progress we might achieve if brilliant minds no longer needed to overcome systemic obstacles to contribute their gifts to humanity’s understanding.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview is a dramatised reconstruction based on historical research into Barbara Low’s life and scientific contributions. Whilst her biographical details, scientific achievements, and historical context are accurately represented, the specific dialogue and personal reflections are imaginative interpretations drawn from documented sources, contemporary accounts, and scholarly research. Low passed away in 2019, making this imagined conversation a tribute to her legacy rather than a factual interview. All technical and historical claims have been verified against available records.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved. | 🌐 Translate

Leave a comment