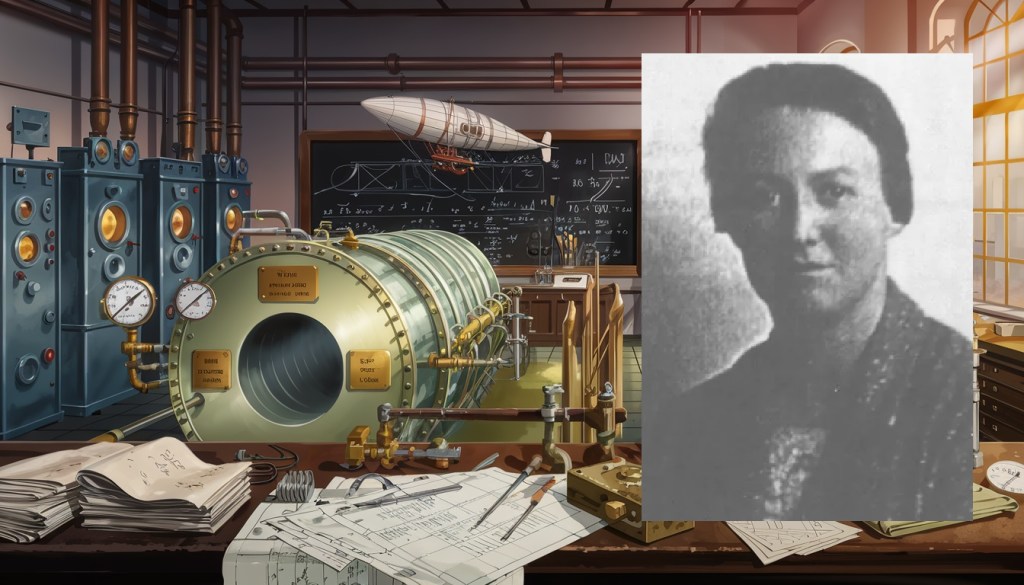

Meet Hilda Lyon (1896-1946) – a grocer’s daughter from Market Weighton who became one of the most significant aeronautical engineers of the twentieth century, though her name remains largely unknown beyond specialist circles. Her revolutionary ‘Lyon Shape’ – a streamlined teardrop design originally developed for airships – ultimately transformed submarine design and continues to influence modern underwater vessels today. She broke barriers as the first woman to win the Royal Aeronautical Society’s R38 Memorial Prize in 1930, yet her career was constantly constrained by the expectations placed on women in engineering and the unfortunate timing of working on technologies that fell from favour.

Good evening, Miss Lyon, and thank you for joining us today. You’ve had a front-row seat to one of the most transformative periods in aviation history, and your work has fundamentally shaped how we think about streamlining in both air and underwater vehicles. Tonight, nearly eight decades after your death, I’d like to explore not just your technical achievements, but the woman behind them – the barriers you faced, the choices you made, and the legacy that continues to influence modern engineering.

Well, I appreciate being remembered at all. One rather expects to fade into obscurity when working on flying machines that the public considers obsolete within a decade of one’s death. Though I must say, it’s curious to be speaking from beyond the grave, as it were – rather like one of those spirit communication sessions that were all the rage in my day.

Your work was anything but obsolete, as we now know. The ‘Lyon Shape’ you developed at MIT became the foundation for modern submarine design, including the USS Albacore, which launched in 1953 and established the teardrop hull form that virtually every submarine uses today. But let’s start at the beginning. What drew a grocer’s daughter from Market Weighton to the mathematics tripos at Cambridge?

Ah, you’ve done your research. My father Thomas sold provisions, it’s true, but he was no ordinary shopkeeper – he valued learning and saw that his youngest daughter had a head for figures. At Beverley High School, I found myself fascinated by the precision of mathematical relationships. There’s something deeply satisfying about a problem with a definitive solution, don’t you think? Unlike so much of life, particularly for women in 1915.

Cambridge was… well, it was Cambridge. I earned my degree in mathematics in 1918, though of course it was merely a ‘title degree’ – women couldn’t actually receive proper degrees until 1948. Rather fitting that I spent my career working on things that didn’t officially exist either, wouldn’t you say?

You went directly from Cambridge into aviation work. What was that transition like?

The Air Ministry offered a six-week course in aeroplane stress-analysis, and frankly, it was the first practical application of mathematics I’d encountered that felt genuinely useful. Not theoretical exercises about trains leaving stations, but real calculations for machines that would actually fly – or fall from the sky if one got the sums wrong.

I started at Siddeley-Deasy in Coventry as a technical assistant. The work was fascinating – analysing the forces on aircraft structures, calculating load distributions – but the career prospects were rather limited. As I told colleagues later in the Women’s Engineering Society, “there was no prospect of promotion or more responsibility for a woman mathematician”. One might spend a year on detailed calculations and design work only to have the project cancelled by some higher authority who’d never held a slide rule.

That led you to George Parnall & Co. in Bristol, where you worked on various aircraft projects. Can you walk us through your approach to structural analysis?

At Parnall, I was calculating stresses in bracing wires for proposed aircraft – biplanes mostly, some quite ambitious designs that never saw production due to the war’s end. My method was as follows: first, I’d establish the load paths through the structure, then calculate the forces at each critical point using static analysis. Remember, we were working with slide rules and mechanical calculators – no electronic computers, though I suppose the principles were similar to what your modern engineers use.

The key was understanding that aircraft structures aren’t simple beams or columns – they’re complex three-dimensional frameworks where forces interact in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. I’d create mathematical models of these interactions, often working through hundreds of calculations to verify a single structural element. Tedious work, but essential. One miscalculation and you’d have a catastrophic failure at altitude.

In 1922, you became an Associate Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society – quite an achievement for someone just six years out of university. Then in 1925, you joined the Royal Airship Works at Cardington to work on the R101. This was the project that would define much of your career. Tell me about that transition.

Airships represented the future of long-distance travel in the 1920s – or so we believed. The R101 was to be the largest flying machine ever built, designed to connect Britain with her colonies in India and Australia. At 777 feet long when finally completed, it was longer than two football pitches placed end to end.

My role was calculating the stresses in the airship’s transverse frames – the ring-like structures that gave the hull its shape and supported the gas bags. These calculations were fiendishly complex because airships flex and twist in flight, unlike rigid aircraft. The frames had to support not just the static loads from the gas bags and structure, but dynamic loads from wind gusts, temperature changes affecting gas pressure, and the constant flexing of the entire hull.

I developed new mathematical approaches for analysing these distributed loads across the frame structures. The work was published as “The Strength of Transverse Frames of Rigid Airships,” which won me the R38 Memorial Prize from the Royal Aeronautical Society in 1930 – the first time any woman had received a prize from the society.

Could you walk us through the technical development of what became known as the ‘Lyon Shape’? I’d like our engineering readers to understand the methodology behind this breakthrough.

Certainly. When I arrived at MIT in 1930 on my Mary Ewart scholarship, I finally gained access to proper wind tunnel facilities – something that had been impossible in Britain. The MIT tunnel had a circular cross-section, closed throat design that allowed for controlled testing conditions.

I was investigating how turbulence affects drag on airship models, specifically looking at the relationship between hull shape and drag coefficient under varying turbulence conditions. Previous airship designs had been based largely on intuition and limited theoretical work, but I wanted quantitative data.

The testing procedure was methodical: I suspended scale models using a two-wire system that allowed free longitudinal movement while constraining lateral motion. The model displacement under various wind speeds was measured using a graduated scale and telescope arrangement outside the tunnel. The drag force was calculated from the formula D = Wh/l, where W was the weight of the model and moving parts, h the displacement, and l the length of the supporting wires.

The critical insight came from the testing of different nose shapes under turbulent conditions. Traditional airship designs used very pointed noses – what seemed aerodynamically logical. But my experiments showed that a blunter, more rounded nose actually produced less drag in turbulent air. The turbulence created by the sharp leading edge was actually increasing overall drag more than the theoretical benefit of the pointed shape.

The optimal shape I developed had a fineness ratio – length to maximum diameter – of approximately 6:1, with a carefully calculated nose radius that balanced pressure drag against friction drag. The mathematical relationship I established showed that for Reynolds numbers typical of full-scale airships, this ‘Lyon Shape’ produced drag coefficients roughly 15-20% lower than conventional pointed designs.

This shape also had the advantage of being more stable in crosswinds and creating less structural stress on the forward frames – a consideration that proved crucial for practical implementation.

The R101 crashed in October 1930, just months after you’d left Cardington for your MIT studies. How did that disaster affect your work and the entire airship program?

The R101 crash was… devastating, both personally and professionally. Forty-eight people died, including Lord Thomson, who had championed the programme, and many of my former colleagues. The technical investigation concluded that weather damage to the forward covering led to gas bag rupture and loss of buoyancy, causing the fatal dive.

But the larger tragedy was how it killed an entire industry overnight. Public confidence in airships vanished, and the government abandoned the Imperial Airship Scheme completely. My work on airship structures suddenly seemed irrelevant – I was an expert in a technology the world had decided was too dangerous to pursue.

At MIT, I found myself in the peculiar position of completing research on airship drag while knowing that commercial airship travel was finished. Rather sobering, really, to realise that technical excellence means nothing if the political will disappears.

But your research at MIT, particularly on turbulence effects, proved far more broadly applicable than airship design alone.

Indeed. Working with Professor Robert Smith, I investigated how atmospheric turbulence affects drag across different body shapes. The work had immediate applications to aircraft design, but I was also thinking about underwater applications. Water behaves as a fluid much like air, after all – the mathematical principles of streamlining apply whether you’re moving through atmosphere or ocean.

My thesis work established that turbulence intensity had different effects on different hull forms. Sharp-nosed shapes suffered proportionally greater drag increases in turbulent flow than blunter shapes. This finding had implications not just for airships, but for any vehicle moving through a fluid medium.

After your year at MIT, you went to Göttingen to work with Ludwig Prandtl, one of the founders of modern aerodynamics. What was that experience like?

Prandtl was brilliant – the father of boundary layer theory and wind tunnel testing. At the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft, I worked on refining the mathematical analysis of my hull shape, particularly understanding how the boundary layer behaves around curved surfaces.

Prandtl’s approach was rigorously scientific – everything had to be measurable and repeatable. He taught me to think not just about individual measurements, but about the underlying physical principles governing fluid flow. That approach proved invaluable when I later returned to Britain and had to work largely independently.

You returned to England in 1932, but instead of resuming your career, you spent several years caring for your ill mother. This was a common dilemma for women of your generation – choosing between career advancement and family obligations.

Yes, Mother fell ill, and as the unmarried daughter, it fell to me to provide care. Society expected it, and frankly, there were few alternatives. I spent those years at home in Yorkshire, but I wasn’t entirely idle. I maintained my research using libraries at Hull and Leeds universities, and I made regular visits to the National Physical Laboratory and Royal Aircraft Establishment.

It was actually during this period that I published some of my most important theoretical papers on streamlining and boundary layer effects. Sometimes isolation forces one to think more deeply about fundamental principles rather than getting caught up in the immediate pressures of institutional research.

But yes, it set my career back considerably. The professional networks I’d built at Cardington and MIT atrophied. When I finally returned to full-time work in 1937, I had to rebuild my reputation almost from scratch.

That return led to your position as Principal Scientific Officer at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough – quite a senior role for a woman in 1937.

The RAE created the position specifically for me, which was both flattering and rather pointed evidence of how few women were reaching senior technical positions. I initially worked on boundary layer suction experiments – investigating whether drawing air through perforated surfaces could reduce drag by keeping the boundary layer attached.

Later, I became head of the Stability Section, working on aircraft handling characteristics. During the war, this included stability analysis for the Hurricane fighter – rather important work, considering what those aircraft faced during the Battle of Britain.

My 1942 paper on longitudinal dynamic stability in gliding flight became something of a standard reference. It established mathematical methods for predicting how aircraft would behave in various flight conditions – essential for pilot training and aircraft design.

Let me ask you about a moment of self-critique. Looking back, is there anything you would have done differently?

Several things, actually. I rather regret not pursuing more practical engineering training alongside my mathematical studies. I always felt somewhat at a disadvantage compared to colleagues who had hands-on workshop experience. The ability to understand how theory translates into actual manufactured components is crucial for an engineer.

I also wonder if I was too focused on proving myself through technical excellence alone. Perhaps I should have been more strategic about building political support for my work, particularly regarding airships. The technical merits of the Lyon Shape were sound, but I failed to adequately communicate its broader applications to decision-makers who might have continued the research.

And frankly, I sometimes wonder if I was too accommodating to the restrictions placed on women in engineering. Perhaps I should have pushed harder against the barriers rather than finding ways to work around them.

Your colleagues at the time were developing competing theories about optimal hull shapes. How did you respond to criticism of your work?

There was considerable debate about whether pointed or blunted nose shapes were superior. Traditional naval architecture favoured sharp bows for surface vessels, and many aerodynamicists assumed the same principle applied to airships and submarines.

My response was always to return to experimental data. I had wind tunnel measurements showing that blunter shapes performed better under realistic conditions – conditions that included atmospheric turbulence, which earlier theorists had largely ignored. The mathematics were clear: while a perfect point might be optimal in completely smooth flow, such conditions don’t exist in the real world.

Some critics argued that my findings applied only to the specific conditions in the MIT tunnel, but subsequent testing proved the Lyon Shape’s advantages across a wide range of scales and conditions. The success of the USS Albacore vindicated the approach, though I sadly didn’t live to see that validation.

Before we finish, I’d like to ask about the modern resonance of your work. Today’s engineers use computational fluid dynamics – solving the same mathematical equations you worked with, but using computers that can perform millions of calculations per second. How do you think this technology might have changed your approach?

Millions of calculations per second? Extraordinary! I spent weeks doing by hand what you describe as happening in moments. But the fundamental principles remain unchanged – you still need to understand the physical phenomena you’re modeling.

I suspect computational methods might have allowed me to explore more complex geometries and flow conditions, perhaps leading to even more refined hull shapes. The ability to visualise three-dimensional flow patterns around curved surfaces would have been invaluable.

But I worry that easy computation might lead to less rigorous thinking about underlying principles. There’s value in working through calculations manually – it forces you to understand what each variable represents and how changes affect the overall system. I hope your modern engineers don’t lose that understanding in the rush to run simulations.

What would you want young women entering STEM fields today to know, particularly those facing their own barriers?

Don’t let anyone tell you that technical work isn’t for women – our minds are perfectly capable of understanding complex systems and solving difficult problems. But also don’t assume that technical excellence alone will be sufficient. You need to communicate your work effectively, build professional networks, and sometimes fight for recognition that should be automatic.

The barriers I faced – being excluded from prestigious societies, denied promotion opportunities, expected to choose between career and family – many of these persist in different forms. But you have opportunities I could never have imagined: formal educational programmes, legal protections against discrimination, and growing recognition that diversity strengthens technical teams.

Use those advantages, but remember that progress requires each generation to push further than the last. Don’t be content with simply being allowed in the room – demand to be heard, and make sure your work has the impact it deserves.

Finally, how would you like to be remembered?

As an engineer who solved problems through careful observation, rigorous analysis and experimentation. The Lyon Shape may be my most visible legacy, but I hope I’m remembered more broadly as someone who demonstrated that women can make fundamental contributions to technical fields when given the opportunity.

And perhaps as someone who understood that good engineering serves human needs – whether connecting distant parts of an empire through airship travel or enabling submarine crews to operate more safely and effectively underwater. Technology should make life better, not just more complicated.

Miss Lyon, thank you for sharing your insights with us tonight. Your work continues to influence engineers around the world, and your example continues to inspire women entering technical careers.

Thank you for remembering. And to your readers – keep asking difficult questions and don’t accept easy answers. The world needs more people willing to challenge conventional wisdom through careful measurement and clear thinking.

Letters and emails

Since our interview with Hilda Lyon, we’ve received an overwhelming response from readers eager to explore her insights further. We’ve selected five letters and emails from our growing community who want to ask her more about her life, her work, and what she might say to those walking in her footsteps.

Emilia Rossi, 34, Fluid Dynamics Researcher, Milan, Italy:

Miss Lyon, you mentioned working with slide rules and mechanical calculators at MIT. I’m curious about the precision limitations this imposed – when you were measuring drag coefficients and calculating fineness ratios for the Lyon Shape, how did you account for measurement uncertainty? Did you develop any clever workarounds to achieve the accuracy needed for such groundbreaking results?

Miss Rossi, your question strikes at the heart of experimental work in my era – we were rather like surgeons operating with garden tools, weren’t we? The precision limitations were considerable, but one learns to work within constraints.

At MIT, our wind tunnel measurements were limited by the mechanical systems available. The drag balance I used could detect force differences of perhaps half a pound, which sounds crude by today’s standards, I’m sure. But for airship models weighing twenty to thirty pounds, this gave us resolution of roughly 2-3% in drag coefficient measurements – adequate for establishing clear trends between different hull shapes.

The real challenge wasn’t the instruments themselves, but controlling all the variables that affect measurement accuracy. Temperature changes altered air density throughout the day, affecting our Reynolds numbers. Vibration from the tunnel motor could introduce spurious readings. Even humidity mattered – it changed the boundary layer characteristics slightly.

My approach was to embrace statistical thinking rather than fight it. I’d run each test configuration multiple times under varying conditions, then look for consistent patterns across the data set. If the Lyon Shape showed 15-20% drag reduction in morning tests, afternoon tests, and evening tests, across different temperatures and pressures, then I could be confident the effect was real despite individual measurement uncertainties.

I also developed what you might call “internal consistency checks.” The drag measurements had to align with basic fluid mechanics principles – if my results violated Bernoulli’s equation or showed impossible pressure distributions, I knew something was amiss with the experimental setup.

Rather like doing mathematics with an unreliable slide rule – you learn to cross-check your calculations using different approaches, and trust results that prove themselves repeatedly under varying conditions.

Wei Zhang, 29, Aerospace Engineer, Shanghai, China:

What if the R101 disaster hadn’t occurred and airship technology had continued developing alongside aeroplanes? Given your expertise in both structural analysis and streamlining, how do you think competition between these technologies might have pushed innovation in different directions? Would we have seen hybrid designs or entirely different approaches to long-distance travel?

Mr Zhang, what a fascinating speculation! Had the R101 not met its tragic end, I believe we would have witnessed the most extraordinary period of aeronautical development – two fundamentally different approaches to flight evolving in parallel, each pushing the other towards greater efficiency.

The competition would have been fierce, particularly for long-distance passenger routes. Aeroplanes in 1930 were still rather limited affairs – the de Havilland Dragon could manage perhaps 400 miles, whilst a properly developed airship could cross continents without refuelling. But aeroplanes were faster, more manoeuvrable, and crucially, they could land at modest airfields rather than requiring enormous hangars.

I suspect this competition would have driven airship development towards much more sophisticated designs. We were already investigating pressure-stabilised hulls – rather like inflatable structures – that could have eliminated the heavy rigid framework entirely. Combined with my streamlining research, such designs might have achieved speeds approaching those of contemporary aeroplanes whilst maintaining their range advantages.

The structural challenges would have been immense, mind you. Pressure hulls require different mathematical approaches to stress analysis – more akin to submarine design than traditional airship work. I daresay my later experience with underwater applications might have proved invaluable in that alternative timeline.

But here’s what intrigues me most: the engine development. Both technologies would have demanded more powerful, lighter, more reliable powerplants. I suspect we’d have seen jet propulsion developed much earlier – perhaps by the late 1930s rather than during the war. Frank Whittle was already thinking about gas turbines in 1930, after all.

The safety implications fascinate me as well. Competition might have forced both industries to develop better weather forecasting, more reliable navigation systems, perhaps even early forms of radar. The R101’s fate was sealed by poor weather intelligence as much as structural failure.

I rather think the world might have been a more interesting place – great silver ships crossing the Atlantic alongside swift aeroplanes, each serving different purposes in a more diverse transportation system.

Zuri Ndlovu, 41, STEM Education Advocate, Cape Town, South Africa:

You spoke about feeling isolated during your caregiving years, yet you continued your research independently. Many women today still face similar choices between family responsibilities and career advancement. What specific strategies did you use to maintain your technical edge during that period, and how did that experience of working outside institutional frameworks actually strengthen your approach to problem-solving?

Miss Ndlovu, you’ve touched upon something rather personal there. Those years caring for Mother were… well, they were difficult in ways I hadn’t anticipated. Not just the isolation from professional colleagues, but the constant worry that one’s skills were growing rusty whilst the field advanced without you.

My first strategy was maintaining what I called my “technical correspondence.” I wrote letters to former colleagues at the RAE and MIT, asking about new developments, sharing my own theoretical work. It’s surprising how much one can accomplish through the post when necessity demands it. I also subscribed to every technical journal I could afford – Flight, the Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society, even German publications when I could obtain them.

But the real revelation was discovering that institutional frameworks, whilst providing resources, can also constrain one’s thinking. At Cardington, I’d been focused on immediate project requirements – calculating stresses for specific airship designs, meeting departmental deadlines. During my Yorkshire years, I had the luxury of pursuing fundamental questions that had always nagged at me.

For instance, I spent months working through the mathematical relationship between boundary layer behaviour and hull shape, something I’d never had time to examine thoroughly whilst rushing between wind tunnel tests and committee meetings. That theoretical work proved invaluable when I later returned to Farnborough.

I also developed what you might call “portable research methods.” Without access to wind tunnels, I learned to extract insights from published data by other researchers, comparing results across different laboratories, identifying patterns that individual experimenters might have missed. Rather like being a scientific detective, piecing together clues from scattered sources.

The emotional challenge was perhaps greater than the technical one. Society expects unmarried daughters to sacrifice career ambitions for family duty – it’s simply what’s done. But I refused to let that sacrifice be total. I maintained my professional identity through my writing and correspondence, even when I couldn’t be physically present in laboratories.

Looking back, those years taught me intellectual independence that served me well throughout the rest of my career. When you can’t rely on institutional support, you learn to think more creatively and trust your own judgement. Rather valuable skills for any woman in engineering, I’d say.

Felipe Andrade, 38, Science Policy Researcher, São Paulo, Brazil:

Looking at how the R101 tragedy effectively killed an entire industry overnight, what do you think about the relationship between public perception of risk and technological progress? Today we see similar debates about nuclear energy, genetic engineering, or artificial intelligence. Based on your experience with airships, what advice would you give to engineers working on technologies that face public scepticism or political opposition?

Mr Andrade, you’ve identified something that troubles me greatly about the relationship between technical progress and public sentiment. The R101 disaster demonstrated how a single catastrophic failure can destroy decades of careful development work – not through technical inadequacy, but through political expedience.

The tragedy wasn’t simply that forty-eight people died, dreadful as that was. The deeper tragedy was how swiftly the government abandoned the entire Imperial Airship Scheme without conducting proper technical analysis. Lord Thomson’s death aboard the R101 eliminated the programme’s strongest political champion, and his successors found it easier to cancel everything than to investigate what had gone wrong and how it might be prevented.

This is where engineers working on controversial technologies must think beyond pure technical merit. We assumed that demonstrating superior performance would be sufficient – that the Lyon Shape’s measurable drag reduction would speak for itself. But public perception operates on entirely different principles than wind tunnel data.

The aeroplane lobby, if I may call it that, was rather clever in this regard. They emphasised incremental improvements and distributed risk – hundreds of small aircraft rather than a few enormous airships. When a single aeroplane crashed, it was tragic but didn’t threaten the entire industry. When the R101 crashed, it represented a significant fraction of Britain’s total airship capability.

My advice to engineers facing public scepticism would be this: master the art of communication as thoroughly as you master your technical discipline. Learn to explain complex concepts in language that politicians and the general public can understand. More importantly, learn to frame your work in terms of human benefits rather than technical achievements.

Consider how differently the airship programme might have fared if we’d emphasised practical advantages – connecting families across the Empire, enabling trade, reducing travel time – rather than focusing on impressive statistics about lifting capacity and range.

Also, develop what I’d call “graceful failure modes.” Design systems that fail safely and obviously, rather than catastrophically and mysteriously. The R101’s structural failure was invisible until it was too late. A technology that fails more frequently but less dramatically might actually gain more public acceptance than one that appears perfectly reliable until it kills everyone aboard.

Finally, cultivate political champions who understand your work well enough to defend it against emotional opposition. Technical excellence without political support is merely an expensive hobby.

Madison Clark, 26, Marine Engineering Student, Vancouver, Canada:

I’m fascinated that your airship research led to submarine applications – that’s such brilliant cross-domain thinking! When you were developing the mathematical principles behind the Lyon Shape, did you consciously consider how fluid dynamics principles might transfer between air and water, or was that connection something you realised later? How do you think engineers today could get better at spotting these kinds of unexpected applications?

Miss Clark, you’ve spotted something that rather pleased me about my own thinking – though I confess it wasn’t entirely deliberate at first. The connection between air and water as fluid media was obvious from a mathematical standpoint, but the practical implications took time to crystallise.

During my wind tunnel work at MIT, I was primarily focused on airship applications, naturally enough. But fluid mechanics is fluid mechanics, whether you’re dealing with air at atmospheric pressure or water at depth. The Reynolds numbers differ, the viscosity varies, but the fundamental equations governing boundary layer behaviour and pressure distribution remain unchanged.

The “eureka moment,” if you will, came whilst I was working through the mathematics of boundary layer separation around curved surfaces. I realised that my findings about optimal nose shapes applied to any streamlined body moving through a viscous medium. The Lyon Shape’s advantage – reducing turbulent wake formation behind the widest section – would be even more pronounced underwater, where the fluid density is so much greater.

I began sketching submarine applications in the margins of my airship calculations. Rather unprofessional behaviour, perhaps, but one’s mind does wander when working through repetitive computations. The potential for underwater craft was extraordinary – submarines of my era were essentially surface ships that could submerge temporarily, with all the hydrodynamic efficiency of a floating brick.

What strikes me about modern engineering education is how compartmentalised the disciplines have become. We had the advantage of working across boundaries simply because the boundaries weren’t yet firmly established. Aeronautical engineering was barely a decade old as a formal discipline – we borrowed freely from naval architecture, mechanical engineering, pure mathematics, even meteorology.

My advice to your generation would be this: cultivate what I’d call “promiscuous curiosity.” When you’re studying fluid flow around aircraft wings, ask yourself how the same principles might apply to ship hulls, or turbine blades, or even blood flow through arteries. The mathematics doesn’t care about the application – a differential equation describing pressure gradients works equally well for air, water, or any other fluid.

Keep a notebook specifically for “irrelevant” observations – sketches, calculations, wild speculations that have nothing to do with your current assignment. Some of my most useful insights came from idle doodling during tedious committee meetings. The mind often makes connections when it’s not trying quite so hard to be systematic.

And don’t be afraid to ask naive questions across disciplinary boundaries. The most interesting innovations often come from applying familiar principles in unfamiliar contexts.

Reflection

What emerges from this conversation with Hilda Lyon is not just the story of a brilliant engineer, but an embodiment of the quiet persistence that drives scientific progress. Her journey – from Cambridge mathematics to wind tunnel experiments, from caring for her mother to challenging established aerodynamic principles – reveals how innovation often flourishes not despite obstacles, but because of the creative problem-solving they demand.

Lyon’s candour about her career interruptions and the political realities that killed the airship industry offers perspectives rarely captured in official histories. Where institutional records emphasise technical achievements, she reveals the human costs of choosing between family duty and professional advancement – dilemmas that persist for women in STEM today. Her acknowledgment of strategic missteps, particularly around communicating research beyond technical circles, provides insight into why transformative work sometimes fails to achieve its deserved impact.

The historical record remains frustratingly sparse on Lyon’s personal motivations and daily experiences. We know her publications and positions, but much about her thought processes, working relationships, and private struggles must be reconstructed from fragments. Her influence on modern submarine design through the Lyon Shape is documented, yet her broader contributions to fluid dynamics methodology deserve greater recognition.

Perhaps most striking is how Lyon’s approach to turbulence research anticipated computational fluid dynamics by decades. Today’s engineers use digital tools to solve the same fundamental equations she worked through by hand, facing similar challenges about communicating complex technical insights to decision-makers and the public.

Her story reminds us that scientific progress depends not just on individual brilliance, but on societies willing to nurture talent wherever it emerges – and to remember those whose contributions shaped our world.

Who have we missed?

This series is all about recovering the voices history left behind – and I’d love your help finding the next one. If there’s a woman in STEM you think deserves to be interviewed in this way – whether a forgotten inventor, unsung technician, or overlooked researcher – please share her story.

Email me at voxmeditantis@gmail.com or leave a comment below with your suggestion – even just a name is a great start. Let’s keep uncovering the women who shaped science and innovation, one conversation at a time.

Editorial Note: This interview represents a dramatised reconstruction based on extensive historical research, including technical papers, biographical records, and archival materials from institutions including MIT, the Royal Aeronautical Society, and the Royal Aircraft Establishment. While Hilda Lyon’s achievements, career timeline, and documented statements are historically accurate, her responses and personality portrayals are creative interpretations designed to illuminate her contributions to aeronautical engineering and the challenges faced by women in early 20th-century STEM fields.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved. | 🌐 Translate

Leave a comment