The annals of industrial innovation are littered with the names of men who changed the world through mechanical ingenuity. Yet buried beneath layers of historical neglect lies the remarkable story of Sarah “Tabitha” Babbitt, a woman whose brilliant engineering insight revolutionised lumber milling and laid the foundation for modern woodworking – all whilst remaining systematically erased from the official record.

This is not merely another tale of overlooked female achievement. It is a damning indictment of how our patent system, designed ostensibly to reward innovation, has perpetuated one of history’s most glaring injustices. Here was a woman whose invention transformed an entire industry, yet she remains absent from the National Inventors Hall of Fame for the simple reason that her religious beliefs prevented her from obtaining a patent.

The Making of an Innovator

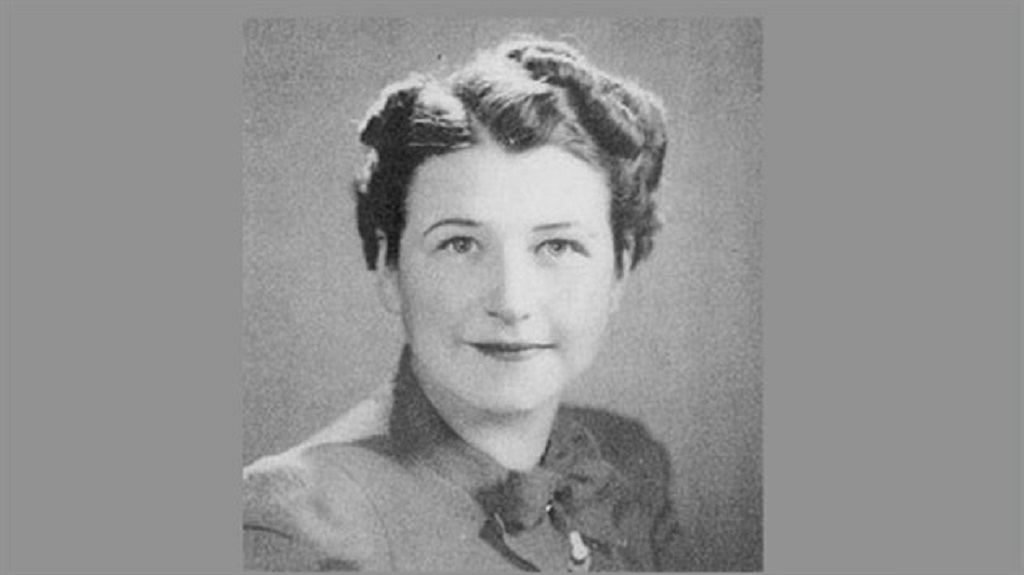

Born on 9th December 1779 in Hardwick, Massachusetts, Tabitha Babbitt entered a world where a woman’s mechanical aptitude was neither expected nor particularly welcomed. The daughter of Seth and Elizabeth Babbitt, her life took a decisive turn at age 13 when she joined the Harvard Shaker community in Massachusetts on 12th August 1793.

The Shakers – formally known as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing – provided an environment radically different from the patriarchal society beyond their borders. Here, gender equality was not merely an aspiration but a lived reality. Women and men shared equally in leadership roles, their voices carried equal weight in decision-making, and their contributions to communal life were valued without regard to sex. This egalitarian ethos would prove crucial in nurturing Babbitt’s inventive spirit.

Within this progressive community, Babbitt thrived as a skilled toolmaker and problem-solver. The Shakers were renowned for their commitment to innovation, particularly in agriculture, construction, and craftsmanship. They understood that God dwelt in the details of their work and in the quality of their craftsmanship. All their devotion, which no longer went to family or home, was channelled into what they made.

The Moment of Breakthrough

Around 1813, Babbitt made an observation that would change industrial history. Watching the community’s sawmill workers struggle with the traditional two-man whipsaw, she identified a fundamental inefficiency that had plagued lumber production for centuries. The whipsaw – a long, straight blade operated by two men – only cut wood on the forward stroke, making the return stroke essentially wasted motion.

This was not merely an abstract problem. The whipsaw method was backbreaking work that required two skilled workers to produce relatively little lumber. One man stood above the log, the other below in a pit, and together they would pull the saw back and forth through the wood. The worker below – the “pit-man” – had to contend with sawdust in his mouth and eyes, whilst both workers expended enormous energy on the non-productive return stroke.

Babbitt’s engineering insight was elegant in its simplicity: what if the cutting motion could be continuous rather than reciprocating? Drawing inspiration from her spinning wheel, she attached a circular blade to the wheel’s mechanism, using the pedal to power the rotary motion. This simple prototype demonstrated that rotary motion could cut in both directions, eliminating wasted energy entirely.

The results were immediate and dramatic. Wood could be cut with continuous motion, no movement was wasted, and the process required only half the manpower of traditional methods. By 1813, a larger version of her design had been installed in the community’s sawmill, where it quickly proved its worth.

The Broader Context of Innovation

To understand the significance of Babbitt’s achievement, one must consider the state of lumber production in early 19th-century America. The traditional methods were not merely inefficient – they were a bottleneck constraining economic development. The whipsaw technique, whilst an improvement over hand-sawing with axes, was still largely a manual process that limited the scale of lumber production.

The lumber industry was entering a period of unprecedented demand. The rapid westward expansion of the United States, the growth of cities, and the emerging railroad network all created voracious appetites for processed timber. Yet the technology for converting trees into lumber remained fundamentally unchanged from medieval times.

Babbitt’s circular saw represented more than a marginal improvement – it was a quantum leap in manufacturing efficiency. Her design enabled continuous cutting, reduced labour requirements, and dramatically increased output. The impact was so significant that her basic design was soon copied by sawmills throughout America.

The Patent System’s Blind Spot

Here we encounter the cruel irony at the heart of Babbitt’s story. The very innovation that should have secured her place in history was prevented from formal recognition by the religious convictions that made her innovation possible. The Shakers’ belief in communal ownership of intellectual property meant that no member could apply for patents, as they believed knowledge should be shared freely with humanity.

This philosophical stance was not unique to the Shakers. Benjamin Franklin, that paragon of American innovation, held similar views. He famously declared, “As we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously”. Franklin never patented his numerous inventions, believing that claiming ownership of ideas would only lead to disputes and hinder progress.

Yet whilst Franklin’s contributions are universally celebrated, Babbitt’s remain largely forgotten. The difference is not in the quality or significance of their innovations, but in the systematic exclusion of women from historical recognition. The patent system, designed to reward and protect innovation, became a tool for perpetuating historical injustice.

The Evidence and the Sceptics

The absence of formal patents has provided ammunition for those who would dismiss Babbitt’s contributions as “Shaker propaganda”. These sceptics point to earlier circular saw designs, particularly Samuel Miller’s 1777 British patent for a circular saw machine. They argue that the concept of the circular saw was already known, and that Babbitt’s claims are merely community folklore.

This criticism reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of innovation. Miller’s patent described a windmill-powered machine that used circular blades, but the patent text suggests that the circular saw blade itself was already a known technology. Miller’s innovation was in the mechanical system for powering the saw, not in the blade design itself.

More importantly, innovation is not merely about being first – it is about practical implementation and widespread adoption. Babbitt’s design was substantially different from Miller’s. Where Miller’s machine was a complex windmill-powered system, Babbitt created a practical, scalable solution that could be easily adopted by working sawmills. Her design was larger, more robust, and specifically optimised for lumber production rather than the general wood-cutting applications Miller envisioned.

The historical record supports Babbitt’s contribution. Shaker communities maintained detailed records of their innovations, and multiple sources confirm that her circular saw design was widely adopted by American sawmills. The technology spread rapidly precisely because it offered such clear advantages over existing methods.

The Broader Pattern of Exclusion

Babbitt’s story exemplifies a broader pattern of how women’s contributions to science and technology have been systematically erased from history. The exclusion operates at multiple levels, from the structural barriers that prevent women from accessing formal recognition to the historiographical biases that diminish their achievements.

Consider the stark statistics. Mary Kies became the first American woman to receive a patent in her own name in 1809 – nearly two decades after the Patent Act of 1790 granted all citizens the right to patent their inventions. The delay was not due to lack of female innovation, but to legal and social barriers that made it nearly impossible for women to hold property, including intellectual property.

Even when women did obtain patents, their contributions were often minimised or attributed to men. Sybilla Masters, the first American to receive any patent, had her inventions registered in her husband’s name because women could not legally own property. The patent was granted “to Thomas Masters… of the sole Use and Benefit of A New Invention found out by Sybilla, his wife”.

By 1850, only 32 patents had been issued to women in the United States, compared to thousands issued to men. The disparity was not due to lack of inventiveness, but to systematic exclusion from the formal mechanisms of recognition and protection.

The Modern Reckoning

The injustice of Babbitt’s exclusion from official recognition has not gone entirely unnoticed. Sam Asano, named by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as one of the 10 most influential inventors of the 20th century, took up her cause in 2015. Asano was outraged to discover that Babbitt’s name was absent from the National Inventors Hall of Fame, despite her revolutionary contribution to industrial technology.

When Asano wrote to the organisation managing the Hall of Fame, he received a response that crystallised the absurdity of the situation: because Babbitt had no patent, she had no place in the listing. The irony was not lost on Asano, who noted that Benjamin Franklin – who also refused to patent his inventions – was similarly excluded from the Hall of Fame.

This rigid adherence to patent requirements as the sole criterion for recognition reveals the fundamental flaw in how we commemorate innovation. The patent system, rather than serving as a neutral recorder of human ingenuity, has become a barrier to acknowledging contributions from those who were systematically excluded from its protection.

The Continuing Relevance

Babbitt’s story resonates powerfully in our contemporary discussions about innovation, recognition, and equity. Current research shows that women account for only 12-13% of patent applications globally. At current rates of progress, gender parity in patenting will not be achieved until 2070.

The underrepresentation of women in patenting is not merely a historical curiosity – it represents a massive waste of human potential. Economic analysis suggests that closing the gender gap in patents could increase GDP by 2.7%. The innovations we are not seeing, the problems we are not solving, the perspectives we are not including – these represent incalculable losses to human progress.

Furthermore, the exclusion of women from formal recognition perpetuates narratives that diminish their contributions to scientific and technological advance. When we fail to acknowledge pioneers like Babbitt, we reinforce the false impression that innovation is primarily a male domain. This, in turn, discourages future generations of women from pursuing careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

The Technology That Changed the World

The circular saw that Babbitt pioneered became one of the most important tools in human history. Her basic design principle – continuous rotary cutting – remains the foundation of modern sawmills, construction tools, and manufacturing processes. Every time a carpenter uses a circular saw, every time a construction worker cuts lumber, every time a factory processes wood products, they are benefiting from Babbitt’s insight.

The efficiency gains were transformational. Where traditional pit-sawing required two skilled workers to produce limited quantities of lumber, circular saws enabled continuous production with reduced labour requirements. This dramatically reduced the cost of lumber, making it accessible for widespread construction and fueling America’s westward expansion.

The circular saw also enabled the development of mass production techniques in the furniture industry. With faster, more efficient wood processing, manufacturers could produce furniture on unprecedented scales. This democratisation of furniture availability improved living standards across socioeconomic classes.

A Question of Justice

The exclusion of Tabitha Babbitt from the pantheon of celebrated inventors is not merely an historical oversight – it is a continuing injustice that demands redress. Here was a woman whose brilliant engineering insight revolutionised an entire industry, yet she remains systematically erased from the official record.

The arguments for dismissing her contributions collapse under scrutiny. Yes, the circular saw concept existed before Babbitt’s innovation. But innovation is not about priority alone – it is about practical implementation, widespread adoption, and transformational impact. Babbitt’s design met all these criteria and more.

The claim that Shaker oral tradition is insufficient evidence is particularly pernicious. It reflects a broader pattern of how women’s contributions are held to impossibly high standards of documentation whilst men’s achievements are accepted on far less rigorous evidence. The detailed Shaker records, the widespread adoption of her design, and the transformational impact on American lumber production provide compelling evidence of her contribution.

The Path Forward

Recognising Babbitt’s contributions requires more than merely adding her name to lists of forgotten inventors. It demands a fundamental reckoning with how we understand innovation, recognition, and historical justice. The patent system, whilst valuable for protecting intellectual property, must not be the sole criterion for acknowledging human ingenuity.

We must expand our conception of innovation to include the contributions of those who were systematically excluded from formal recognition. This means looking beyond patents to examine the practical impact of inventions, their adoption by industry, and their long-term influence on human progress.

Educational curricula must be revised to include the stories of pioneering women like Babbitt. Students learning about the Industrial Revolution should understand that innovation was not solely a male endeavour, but included brilliant women whose contributions were marginalised or erased.

The National Inventors Hall of Fame and similar institutions should revise their criteria to acknowledge inventors who were prevented from obtaining patents due to systematic exclusion. The absence of a patent should not disqualify someone from recognition when that absence resulted from discrimination rather than choice.

The Lasting Legacy

Tabitha Babbitt’s story embodies the best and worst of human innovation. Her brilliance, creativity, and practical insight represent the finest traditions of engineering problem-solving. Yet her systematic exclusion from historical recognition represents our continued failure to acknowledge the full scope of human achievement.

In our current era of technological transformation, when we desperately need diverse perspectives and innovative solutions, we cannot afford to ignore half the population’s contributions. The innovations we need for the future will require the full participation of all human talent, regardless of gender.

Babbitt’s circular saw continues to cut through wood around the world, a tribute to the lasting power of brilliant engineering insight. It is time that history cut through the barriers that have obscured her remarkable contribution. She deserves nothing less than full recognition as one of the pioneering innovators who shaped the modern world.

The measure of a just society is not merely how it treats its most celebrated citizens, but how it acknowledges the contributions of those who were systematically excluded from recognition. By honouring Tabitha Babbitt, we honour not just her individual achievement, but the countless women whose innovations remain hidden in the shadows of history. Their brilliance demands our recognition, and our future depends on ensuring that such systematic exclusion never happens again.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment