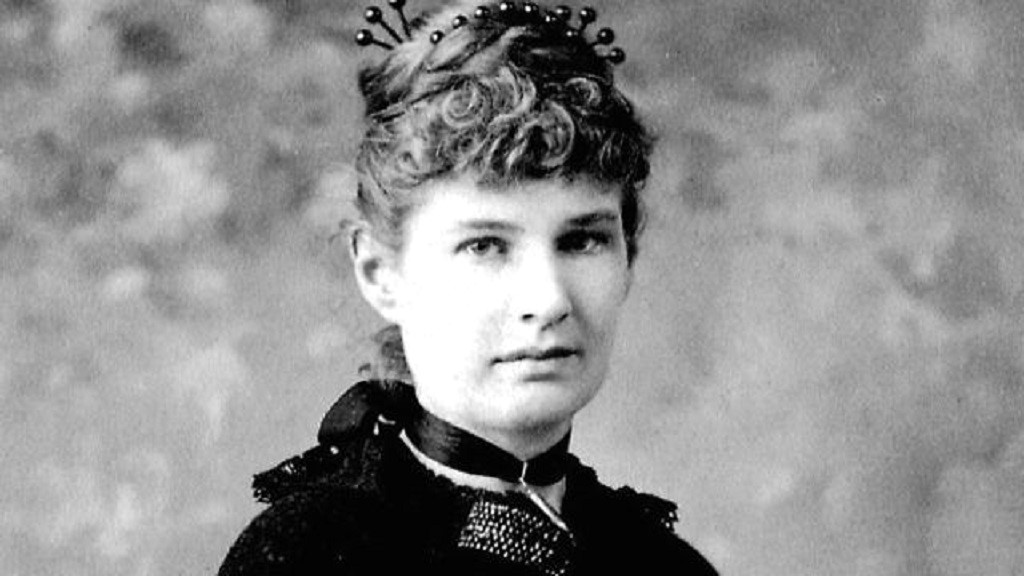

Anna Kingsford’s story is one of breathtaking determination and principled rebellion. Here was a woman who refused to bend to the establishment’s expectations, who challenged the very foundations of medical practice, and who forged a path that no one else dared to tread. Yet her remarkable achievements have been systematically overlooked by medical history, buried beneath prejudice and professional spite.

The Woman Who Wouldn’t Compromise

At a time when women were barred from English medical schools, Kingsford did what others deemed impossible. She travelled to Paris in 1874, enrolling in the prestigious École de Médecine at the age of 28. This was no idle pursuit of social status – she had a mission. After witnessing the barbaric practice of vivisection, she was determined to prove that medical education was possible without torturing animals.

For six gruelling years, Kingsford endured the hostility of male classmates and professors who made no secret of their disdain for women in medicine. She was often the only woman in her class, forced to sit through lectures where conscious animals were cut open alive whilst students looked on. The psychological toll was immense. She described her medical education as a “descent into hell”, yet she persevered with iron determination.

A Thesis That Changed Everything

In 1880, Kingsford achieved what the medical establishment said was impossible – she graduated as one of the first English women to obtain a medical degree, having never once participated in vivisection. Her thesis, L’Alimentation Végétale de l’Homme, was a groundbreaking work on vegetarian nutrition that challenged the meat-obsessed medical orthodoxy of the day.

The thesis was revolutionary in its scope, combining rigorous scientific analysis with moral philosophy. Kingsford argued that vegetarianism was not merely a dietary choice but the foundation of all human progress – physical, moral, and spiritual. She demonstrated through organic chemistry and evolutionary theory that humans were naturally frugivorous, not carnivorous. This was heretical stuff in an era when roast beef was considered essential to British strength and civilisation.

The Perfect Storm of Prejudice

Kingsford’s tragedy was that she stood at the intersection of multiple forms of establishment hostility. As a woman, she faced the brutal sexism of Victorian medicine. As an anti-vivisectionist, she challenged the scientific orthodoxy that was rapidly gaining power. As a vegetarian, she threatened the cultural and economic foundations of British society. And as a spiritualist who integrated mystical beliefs with scientific practice, she was dismissed as a crank by the increasingly materialist medical profession.

Her opposition to vivisection was not born of squeamishness but of principled moral conviction. She founded the Hermetic Society in 1884, which became a breeding ground for occult and mystical thought that would later influence the Golden Dawn. Her collaboration with Edward Maitland produced The Perfect Way, a work that attempted to reconcile Christianity with ancient wisdom traditions. This made her even more suspect to the medical establishment, which was keen to establish its scientific credentials.

The System’s Revenge

The medical establishment’s response was predictable and vicious. They couldn’t attack her qualifications – she had graduated with distinction from one of Europe’s most prestigious medical schools. They couldn’t question her dedication – she had devoted her life to the cause of healing. So they attacked her character, her beliefs, and her associations.

Her integration of spiritual beliefs with scientific practice was ridiculed as evidence of an unfit mind. Her vegetarianism was dismissed as a fad. Her opposition to vivisection was portrayed as emotional hysteria rather than ethical principle. The fact that she was a woman made it easier to dismiss her as inherently irrational.

A Life Cut Short

Kingsford’s health, never robust, was further compromised by the stress of her battles with the medical establishment. She contracted pneumonia in 1886 after visiting Louis Pasteur’s laboratory in Paris, possibly as part of her anti-vivisection investigations. The pneumonia developed into pulmonary tuberculosis, which killed her in February 1888 at the age of just 41.

Her early death was a catastrophe for the causes she championed. Had she lived another twenty years, she might have established a lasting legacy in medical education, animal rights, and women’s advancement. Instead, her work was quickly forgotten, her ideas dismissed as the eccentric musings of a woman who had overstepped her proper bounds.

The Continuing Relevance

Yet Kingsford’s vision remains startlingly relevant. Her advocacy for vegetarianism anticipated modern concerns about animal welfare, environmental sustainability, and human health. Her opposition to vivisection prefigured contemporary debates about animal experimentation and the ethics of medical research. Her integration of spiritual and scientific perspectives echoes current discussions about holistic medicine and the limitations of purely materialist approaches to healing.

Most importantly, her insistence that medicine should be grounded in compassion rather than cruelty offers a powerful alternative to the increasingly impersonal, technology-driven healthcare of today. She believed that the quality of a doctor’s character was inseparable from their ability to heal. This view was dismissed as sentimental nonsense by the Victorian medical establishment, but it resonates strongly with patients who feel dehumanised by modern medical practice.

The Establishment’s Blind Spot

The medical establishment’s systematic neglect of Kingsford reveals its own moral blindness. Here was a woman who achieved the highest academic qualifications, who developed innovative approaches to nutrition and health, who championed the rights of the vulnerable, and who refused to compromise her principles for professional advancement. Yet she has been written out of medical history as if she never existed.

This erasure is not accidental. Kingsford represents everything the medical establishment has tried to suppress – the integration of ethics with science, the primacy of compassion over profit, the recognition that healing involves more than just physical intervention. Her memory threatens the narrative of medical progress that portrays the profession as steadily advancing from ignorance to enlightenment.

A Legacy Denied

The tragedy of Anna Kingsford is not just that she died young, but that her contributions have been systematically ignored by those who should have celebrated her achievements. She was a pioneer who opened doors for women in medicine, an innovator who challenged orthodox thinking about nutrition and health, and a moral leader who refused to separate scientific practice from ethical principle.

Her story should be taught in every medical school as an example of courage, integrity, and vision. Instead, it has been buried beneath decades of professional prejudice and institutional amnesia. The medical establishment that claims to honour its pioneers has chosen to forget one of its most remarkable figures, simply because her vision was too challenging, her principles too uncompromising, and her gender too inconvenient.

Anna Kingsford deserves better than historical oblivion. Her life and work offer a powerful reminder that true medical progress requires not just scientific knowledge but moral courage – the courage to challenge established practice, to defend the vulnerable, and to insist that healing must be grounded in compassion rather than cruelty. In forgetting her, we have impoverished ourselves and betrayed the very ideals that medicine claims to serve.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment