17 Dawson Street, Holbeck

15th November, 1885

William,

I have begun this letter a dozen times, only to tear each attempt into pieces and throw them upon the fire. The words will not come as they should. How does one write of such things?

Our little Edward is gone.

He died on the 3rd of November, a Tuesday morning when the frost had turned our windows to sheets of ice. I held him as he drew his final breath, William. His poor little chest simply could not fight any longer against the fever that had settled there. Dr. Halewood said it was the lung fever – pneumonia, he called it – brought on by the persistent cough that had plagued our boy since autumn began.

Those final days blur together in my memory like watercolours left in the rain. Edward’s breathing grew so laboured that I could hear it from the kitchen below. Mrs. Braithwaite came every few hours to help me tend him, bringing broths and tisanes that he could barely swallow. Margaret and young William took turns sitting beside his bed, reading to him from the picture books you bought last Christmas. They were so brave, our children, though I could see the fear in their eyes.

The fever took hold on Sunday evening. By Monday, our little boy was burning as though he carried fire within his small body, yet shivering so violently that no number of blankets could warm him. I bathed his face with cool cloths and whispered every prayer I knew, but still the fever climbed. Mrs. Patterson brought her late husband’s medicine – a tonic from the chemist that had helped him through the consumption – but Edward was too weak to keep it down.

When the end came, it was gentle. The terrible struggle in his chest simply… stopped. He opened his eyes once more, looked directly at me, and smiled – such a peaceful smile, William, as though he saw something beautiful waiting for him. Then he closed his eyes and was gone.

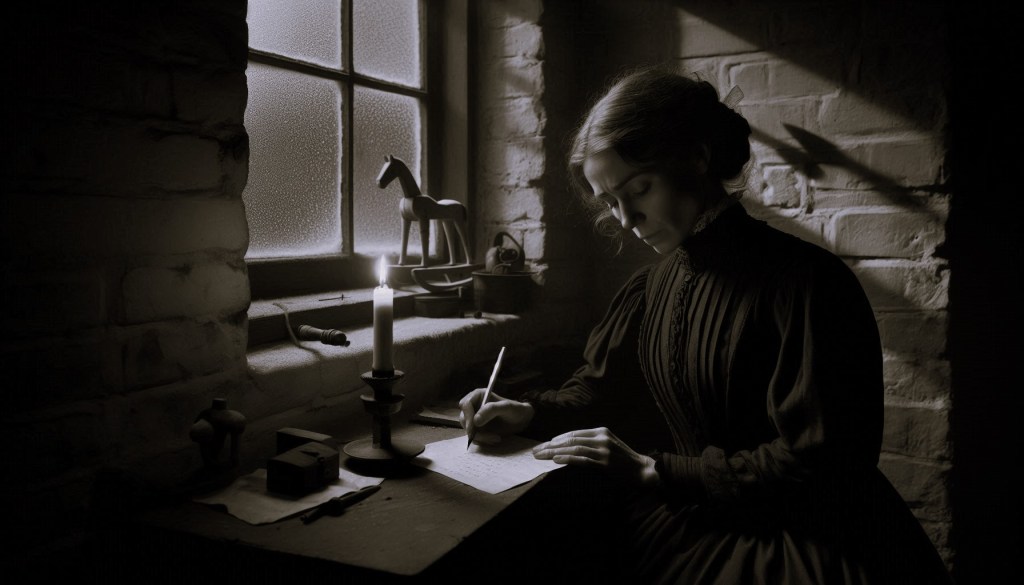

I cannot write of this without weeping. The paper grows spotted with my tears, but I must tell you everything.

Mrs. Henderson organised the collection for the funeral. Our neighbours gave what they could – some pennies, some shillings, Mrs. Kelly even contributed her late mother’s lace for Edwards’s burial clothes. The coffin was built by Mr. Patterson, who would accept no payment for his labour. Small and white it was, with brass handles that caught the December light as we carried it to St. Bartholomew’s.

Reverend Linton spoke beautiful words about little children being called home to God’s garden, where they wait for their parents to join them someday. The choir sang “Abide With Me,” and I thought my heart would break entirely when young voices rose in that cold church. Margaret held my hand throughout the service, whilst William stood straight as a soldier beside me, trying so hard to be the man of the household in your absence.

We buried our boy in the parish cemetery, beneath the old oak tree where the children used to play. Mrs. Braithwaite brought winter flowers – late chrysanthemums and holly branches – to place upon the small grave. The whole street came to pay their respects, William. Even Mr. Wrigley from the foundry, who barely knew us, removed his hat and stood with bowed head as we said our farewells.

The house feels so empty now. Margaret has moved her bed into my room, claiming she grows frightened sleeping alone, though I suspect she worries more about her mother than about ghosts. Young William has assumed responsibilities beyond his years, carrying coal and helping with the washing without being asked. They are good children, our remaining two, but they move through our rooms like small shadows of their former selves.

I rage sometimes, William. I rage at God for taking our innocent boy. I rage at this world that allows children to die for want of proper medicine and adequate heat. And yes, I confess, I rage at you for being so far away when we needed you most. In my darkest moments, I wonder what good your Indian gold will do us if our children perish whilst you pursue it.

But then I remember that you left to secure their futures, not knowing that fate would steal one of them whilst you laboured beneath foreign stars. The fever might have claimed Edward regardless of your presence – Dr. Halewood said the lung weakness would have made him vulnerable to any illness. Still, I needed you here, William. I needed your strength and your comfort during those terrible days when our little boy fought for each breath.

The financial strain has become severe without your expected remittances. Edward’s illness required medicines and additional coal to keep him warm – expenses that drained our small reserves. The funeral costs, despite our neighbours’ generosity, exhausted the last of our savings. I’ve taken additional mending work, sitting up late into the night by candlelight to repair garments for families who can afford to pay for such services.

Mrs. Atkinson at the mill has offered me full-time employment – six days weekly in the weaving shed. The wages would help substantially, but it would mean leaving Margaret and William alone from dawn until evening. They insist they can manage, our brave children, but I hesitate to burden them with such responsibility whilst they grieve their brother’s loss.

Your letters speak of difficulties at the goldfields, of delayed equipment and flooding problems. I understand that circumstances have proven different from what the recruiters promised, but I must ask – when might you return to us? Can you secure passage home by spring? Our family, reduced now to three, needs you here more than we need the uncertain profits of distant mines.

I’ve kept Edward’s favourite toy – the wooden horse you carved for his second birthday. It sits upon the mantelpiece beside your piece of gold-bearing quartz, reminders of the father who shaped it with such love and the distant land where you toil for our welfare. Margaret speaks to it sometimes, telling the horse about her day as though Edward might somehow hear her words.

The winter has been particularly harsh, with snow falling almost daily since November. Our little house grows cold despite our best efforts to conserve coal, and I worry constantly about Margaret and William falling ill. Mrs. Braithwaite checks on us regularly, often bringing soup or bread, though I know she has little enough for her own family. Such kindness reminds me that whilst we may be poor in coin, we remain wealthy in neighbours who care for one another.

Write to me soon, my dear husband. Tell me honestly about your circumstances and your prospects for returning home. We need you here – not as a provider of distant gold, but as a father and husband whose presence might help heal the wounds that Edward’s death has left in our small family’s heart.

I remain, despite everything, your loving wife,

Mary

P.S. – I’ve enclosed a lock of Edward’s hair, cut the morning before he died when the fever had not yet ravaged his dear face. Keep it with you always, that you might remember the son who loved his papa even in his final hours.

◄ Go back to part 5 | Continue to part 7 ►

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment