Kolar Gold Fields, Mysore, India

22nd June, 1885

My Beloved Mary,

At last I can write to you from the goldfields themselves, though I scarcely know where to begin in describing this most extraordinary place. Your husband has truly arrived in another world, my dear – one that bears little resemblance to the Yorkshire hills we know so well, yet one that holds wonders I could never have imagined.

The journey from Bombay was an adventure in itself – three days by train across landscapes that seemed to shimmer like mirages in the fierce heat. The temperatures here, Mary, are beyond anything I experienced even during the hottest summers at home. By midday, the very air seems to burn, and I find myself seeking shade with the desperation of a drowning man seeking air. The company representative who met us at Bangalore station – a thin, perpetually perspiring fellow named Penrose – warned us that June marks the beginning of the hot season, and that we’d best accustom ourselves quickly to what he cheerfully termed “India’s furnace.”

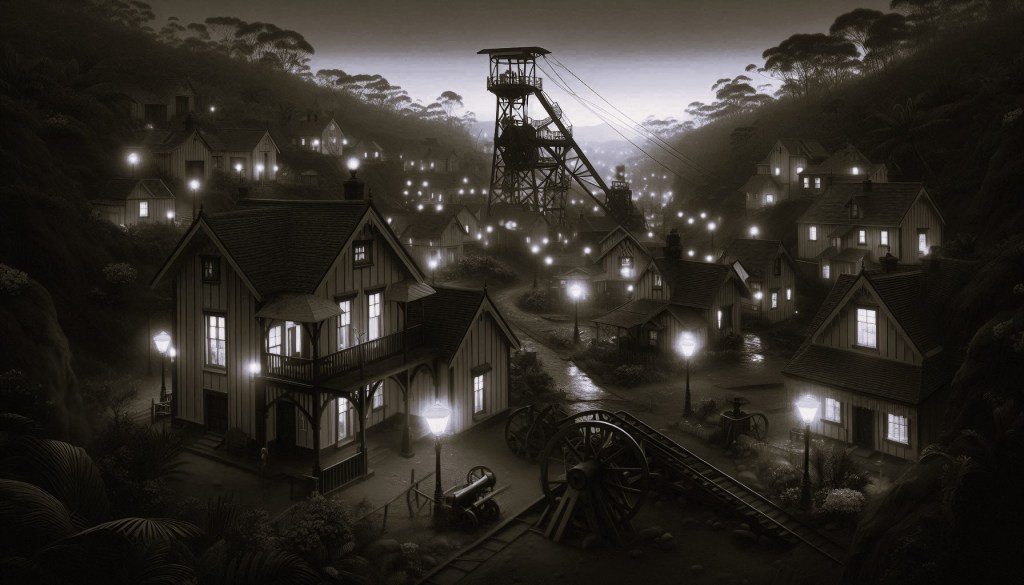

But oh, my darling, when we first glimpsed the goldfields in the distance, I understood why they call this place “Little England.” Rising from the red earth like a vision from a fairy tale stands a proper English town – neat rows of bungalows with gardens, a club house with wide verandahs, even a church with a bell tower that chimes the hours just as St. Bartholomew’s does back in Holbeck. The European quarter, as they call it, looks for all the world like a prosperous village transplanted wholesale from the Cotswolds, complete with flower beds and manicured lawns that somehow flourish in this alien soil.

Most remarkable of all – and here you must prepare yourself for something that will sound like the ravings of a madman – the entire settlement glows with electric light! Yes, Mary, electric light, just as the newspapers describe in those fantastical articles about London’s grand exhibitions. When darkness falls over the goldfields, hundreds of brilliant white lamps illuminate the streets, the mine workings, and even the humblest offices. After twenty years of working by candlelight in Middleton’s depths, I confess I stood slack-jawed like a country yokel at his first fair, watching this miraculous radiance banish the tropical night. The native workers gather each evening just to stare at this wonder, and I cannot blame them – it seems like captured starlight made to serve man’s convenience.

The mining operations themselves are beyond anything we have in Yorkshire. The machinery is American-made, vast and thunderous, with steam engines that dwarf anything I’ve seen. They’ve sunk shafts deeper than any in England – the Champion Reef, which produces most of the gold, descends over a thousand feet into the earth. The scale of it all makes our Middleton workings seem like children’s sandcastles. They extract rock here with an efficiency that would astound the Yorkshire mine owners, crushing ore with stamps that shake the very ground beneath our feet.

However, I must confess that my own situation has proven somewhat different from what the recruiters in Leeds led me to expect. Rather than being assigned to the famous Champion Reef, as Mr. Barstow from John Taylor & Sons had suggested might be possible, I’ve been placed at the Oriental Mine – a smaller operation on the outskirts of the main workings. The supervisor, a Scotsman named MacLeod who speaks with such a thick brogue that even I struggle to understand him, explained that new arrivals must “prove themselves” before earning positions at the more productive mines.

The Oriental presents challenges that test even my years of Yorkshire experience. The rock here is harder than our familiar coal seams, shot through with quartz that dulls our tools with maddening frequency. Worse still, we battle constant flooding from underground springs that seem to defy all attempts at proper drainage. My knowledge of water management from the Middleton workings has proven valuable – indeed, MacLeod grudgingly admitted that “you Yorkshire lads know your way around troublesome water” – but the sheer volume here requires techniques I’m still learning.

The workforce is unlike anything I could have imagined, Mary. Men from every corner of the Empire labour side by side – Cornish miners and other experienced miners like myself – though fewer than expected, work alongside Tamils, Telugus, and Kannadigas whose languages sound like music to my untrained ear. There are even Chinese coolies and Afghan hill-men, each group keeping largely to their own kind but united in the common pursuit of extracting gold from this stubborn earth. The social divisions are as rigid as the rock we break – Europeans, both staff and skilled workers, occupy the higher positions, whilst the Indian workers form the backbone of the labour force under a complex hierarchy I’m still attempting to understand.

The company rules here are stricter than anything we knew at Middleton. They operate what they call the “Mines Out” system – we must be ready for work at the sound of the morning siren, and heaven help the man who’s late to his shift. Tardiness results in loss of pay, and repeated offences can mean dismissal and immediate expulsion from the goldfields. The overseers watch us with the vigilance of hawks, recording our every movement and measuring our output against quotas that seem to increase each week.

My accommodation, whilst clean and adequate, is far from the comfortable bungalow I had pictured during those optimistic conversations in the John Taylor & Sons office. I share a dormitory-style building with five other European miners, each of us allotted a narrow bed, a wooden chest, and little else. The building sits in what they generously term the “skilled workers’ quarter” – a collection of long, low structures that lie between the grand European residences and the sprawling native quarters. We have access to a mess hall where the food, whilst filling, bears little resemblance to your wonderful cooking. Curry and rice form the staples, seasoned with spices that initially burned my throat but to which I’m gradually becoming accustomed.

The wages, I’m told, will be calculated based on productivity rather than the fixed sums mentioned during recruitment. This “results-based remuneration,” as the company terms it, means that my earnings depend entirely upon how much gold-bearing ore our team extracts each week. MacLeod assures me that diligent workers can earn far more than the base wage, but he’s been notably vague about specific amounts. My first month’s pay has been delayed whilst they “assess my contribution to operations,” though I’m promised it will arrive with the July disbursement.

Despite these concerns, I remain optimistic about our prospects, my love. The gold is certainly here – I’ve seen nuggets the size of walnuts brought up from the deeper workings, and the company’s investments in machinery and infrastructure speak to the field’s profitability. My Yorkshire experience with difficult geology serves me well, and several of the Cornish veterans have remarked favourably on my understanding of rock formations and water management. MacLeod himself has hinted that productive workers might earn advancement to the Champion Reef operations, where the rewards are substantially greater.

The climate remains my greatest challenge. The heat saps one’s strength with relentless efficiency, and I find myself drinking enormous quantities of water just to maintain my vigour. The onset of what they call the monsoon season promises some relief from the temperature, though the veterans warn of flooding and disease that come with the rains. I’ve already witnessed several European miners succumb to fever and exhaustion, though the company physician – a competent gentleman named Dr. Stewart – assures me that most ailments prove temporary for men of robust constitution.

Tell the children that their father works now in a land where the very earth glows with electric fire, where elephants carry loads through streets lined with palm trees, and where the sun shines with such intensity that it turns the sky white as milk by midday. Young William would marvel at the great machines that crush rock with the force of giants, whilst Margaret would delight in the brilliant birds – creatures with plumage more vivid than any dyes we know at home – that fill the trees around our compound.

I think of you constantly, particularly in the early morning hours before the heat becomes unbearable, when the goldfields lie peaceful under a sky painted with colours I lack words to describe. The thought of our reunion and the prosperity this venture will bring sustains me through the most challenging moments. I’ve already begun calculating how much I might accumulate by Christmas, and though the exact figures remain uncertain, I’m confident that my sacrifice will prove worthwhile for our family’s future.

Give my love to our dear children, and tell them their father labours beneath stars so different from Yorkshire’s that he feels he’s mining on another world entirely. Yet every ounce of gold we extract brings us closer to security and comfort at home.

Kiss them for me, and keep faith in your devoted husband’s determination to make our fortune in this strange and wondrous land.

Your loving husband,

William Baldwin

P.S. – I’ve enclosed a small piece of gold-bearing quartz that I chipped from the Oriental Mine’s latest working. Let the children hold it and know that their father touches such treasure daily in his efforts to secure their future. The company allows each worker to keep small specimens as souvenirs, though naturally all significant finds belong to John Taylor & Sons.

◄ Go back to part 2 | Continue to part 4 ►

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment