The question of what makes you “you” has become the philosophical equivalent of political dynamite—explosive, deeply divisive, and impossible to defuse. What was once a genteel academic debate has transformed into a fierce intellectual war zone, with implications that stretch far beyond university seminar rooms into courtrooms, laboratories, and the very foundations of human dignity[1,2].

The battle lines are drawn between those who insist there must be some essential core that persists through time—be it soul, memory, or consciousness—and those who follow David Hume’s radical insight that we are nothing more than “bundles” of experiences with no fixed centre[3]. This isn’t merely abstract theorising. These competing visions of selfhood determine whether we can hold someone responsible for crimes committed decades ago, whether artificial intelligence might one day deserve rights, and whether the person with dementia bears any meaningful connection to who they once were[4,5].

The Essentialist Camp: Searching for the Unchanging Core

Essentialist theories of personal identity represent the intuitive position—that there must be something that makes you distinctively you across time[1,6]. These theories come in several varieties, each proposing a different candidate for this essential core.

The soul theory, tracing back to Aristotle, posits that personal identity resides in a non-physical essence that transcends bodily changes[6]. Yet this view has fallen from philosophical grace, not merely because of its metaphysical commitments, but because it fails to engage with the practical puzzles that make personal identity philosophically urgent.

More influential has been John Locke’s memory theory, which grounds personal identity in psychological continuity[7]. Locke famously defined a person as “a thinking intelligent being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider itself as itself”[1][7]. On this view, you are the same person as your childhood self precisely because you can remember having those childhood experiences.

But Locke’s theory immediately runs into difficulties. Thomas Reid’s “brave officer paradox” exposes the problem: an elderly general remembers his experiences as a young officer, and the young officer remembered being flogged as a boy, but the general cannot remember the boyhood flogging[7]. If memory is the criterion of identity, we reach the absurd conclusion that the general both is and isn’t the same person as the boy.

Contemporary psychological continuity theories attempt to solve these problems by requiring not direct memory connections but overlapping chains of psychological connections—including beliefs, desires, personality traits, and intentions—that are appropriately caused[8]. These theories acknowledge that we don’t need to remember everything about our past to remain the same person, as long as there’s sufficient psychological overlap.

Yet even sophisticated psychological theories face the problem of fission cases. Derek Parfit’s thought experiments involving brain splitting reveal the inadequacy of our ordinary concept of identity[9,10]. If your brain were divided and each half transplanted into different bodies, creating two psychologically continuous persons, which one would be you? The logic of identity demands a single answer, but psychological continuity suggests both[11].

The Bundle Theory: Hume’s Radical Dissolution

David Hume delivered perhaps the most devastating critique of essentialist thinking about personal identity[3]. When Hume introspected, he found no unified self—only a stream of perceptions, thoughts, and sensations. “I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception,” Hume wrote[3].

The bundle theory that emerged from Hume’s insights holds that there is no fixed self—we are simply collections of experiences and perceptions connected in certain ways[3]. This view finds surprising resonance in Buddhist philosophy, where the doctrine of anātman (no-self) similarly denies the existence of a permanent, unchanging essence[12,13].

Contemporary neuroscience provides some support for bundle-like views. Research distinguishes between “self” as immediate, right-hemisphere experience and “identity” as reflective, left-hemisphere, linguistically-mediated construction[14]. This neurological evidence suggests that what we call the self might indeed be more fragmented and constructed than our introspective experience suggests.

The bundle theory’s strength lies in its honesty about the fluidity of human experience. We do change dramatically over time—in personality, beliefs, values, and even fundamental aspects of character. The theory acknowledges this reality rather than desperately seeking some unchanging core that may not exist.

Where Philosophy Meets Hard Reality: Ethics and Responsibility

These competing theories of personal identity aren’t merely academic curiosities—they have profound implications for moral and legal responsibility[4]. If the psychological continuity theory is correct, then someone who undergoes radical personality change due to brain injury might genuinely not be the same person who committed past crimes. If the bundle theory is accurate, our entire framework of holding people responsible for past actions becomes deeply problematic.

The stakes become particularly acute in cases of dementia. Research reveals that caregivers are most likely to view dementia patients as having lost their identity when moral beliefs and behaviours change, rather than when memory fails[5]. This suggests that our intuitive concept of personal identity is closely tied to moral continuity—we remain ourselves as long as we maintain our core moral commitments[5].

Frankfurt cases in moral philosophy further complicate matters by challenging the connection between alternative possibilities and moral responsibility[15]. If someone acts according to their own desires but couldn’t have done otherwise due to external constraints, are they still morally responsible? These cases suggest that personal identity and moral responsibility might be more complex than either essentialist or bundle theories allow.

The Artificial Intelligence Challenge

The rise of artificial intelligence has transformed these philosophical debates from theoretical exercises into urgent practical questions[16]. If consciousness and identity can emerge from sufficiently complex information processing, then AI systems might eventually qualify as persons deserving moral consideration.

Current debates about AI consciousness and identity draw heavily on theories of personal identity developed for humans[16]. Those who favour psychological continuity theories might be more willing to grant personhood to AI systems that demonstrate appropriate cognitive capacities. Bundle theorists might be even more liberal, seeing no principled difference between biological and artificial collections of experiences.

The transhumanist project of mind uploading represents the ultimate test case for theories of personal identity[17]. Would a perfectly accurate digital copy of your brain patterns be you, or merely a copy that shares your memories? Essentialist theories that ground identity in biological continuity would deny survival through uploading, while psychological theories might affirm it[17].

The Narrative Turn: Identity as Storytelling

Contemporary philosophers like Alasdair MacIntyre have proposed narrative theories of personal identity that attempt to bridge the gap between essentialist and bundle approaches[18,19,20]. On this view, we are the stories we tell about ourselves—our identity consists in the coherent narrative we construct to make sense of our experiences over time[20].

The narrative approach acknowledges the constructed nature of identity emphasised by bundle theorists while preserving the continuity and coherence that essentialist theories seek to explain[19]. We remain the same person not because of some unchanging essence or psychological connections, but because we weave our experiences into a coherent life story.

This narrative conception of identity has found support in developmental psychology and psychoanalysis, where therapeutic progress often involves helping patients construct more coherent and empowering stories about their lives[20]. The approach also resonates with postmodern insights about the constructed nature of identity, while avoiding the complete dissolution of selfhood that some find troubling in pure bundle theories[21].

Beyond the False Dichotomy

Perhaps the most profound insight emerging from contemporary debates is that both essentialist and bundle theories capture important truths about human experience while missing others. We do have a sense of continuity and persistence that essentialist theories attempt to explain, but we also experience the fluidity and change that bundle theories emphasise.

The solution may lie not in choosing between these approaches but in recognising that personal identity itself is a more complex and multifaceted phenomenon than any single theory can capture[13,5]. Different contexts may call for different concepts of identity—legal responsibility might require one approach, while therapeutic relationships might benefit from another.

What remains clear is that these debates will only intensify as neuroscience reveals more about the constructed nature of self-experience, as artificial intelligence approaches human-level cognition, and as biotechnology offers new possibilities for altering human nature. The fractured mirror of personal identity reflects not just philosophical confusion but the genuine complexity of what it means to be human in an age of unprecedented technological and scientific advancement.

The stakes could hardly be higher. How we understand personal identity shapes how we treat those with dementia, how we design AI systems, how we assign moral and legal responsibility, and ultimately how we understand our own existence. Philosophy’s most contentious battleground is also its most consequential.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

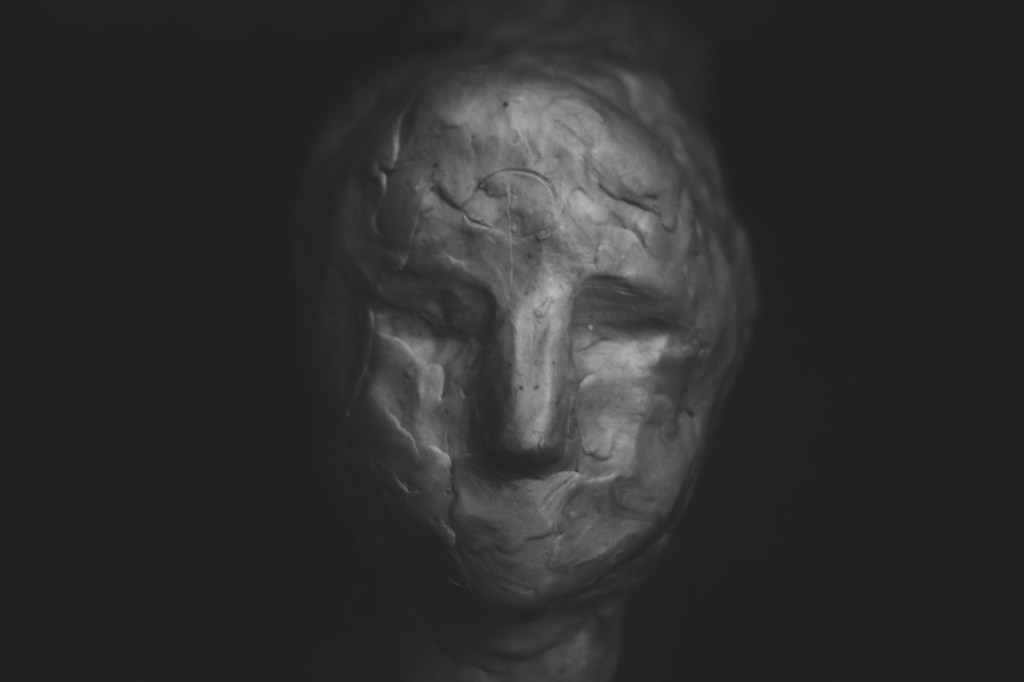

Photo by Alexander Voronov on Unsplash

References:

- https://philarchive.org/archive/OLSAPE

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31301583/

- https://johnstoszkowski.com/blog/the-bundle-theory-of-self

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/identity-agency-moral-responsibility

- https://philarchive.org/archive/GLIDYR

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/theories-personal-identity-philosophy-mind

- http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1683/the-lockean-memory-theory-of-personal-identity-definition-objection-response

- https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/personal-identity/v-2/sections/psychological-continuity-theories

- https://www.uvm.edu/~lderosse/courses/metaph/parfit.pdf

- https://www.reddit.com/r/askphilosophy/comments/1b78xoz/confused_about_derek_parfits_view_on_personal/

- https://www.peterxichen.com/blog/derek-parfit-and-personal-identity

- https://philosophybreak.com/articles/anatman-buddhist-doctrine-of-no-self-why-you-do-not-really-exist/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00124/full

- https://www.psychstudies.net/post-2/

- https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:85c28749-d13f-4285-a677-68cdaddbbf42/files/s7p88ch175

- https://ijgis.org/home/article/view/8

- https://www.academia.edu/24268306/Mind_Uploading_The_Hard_Problem_of_Transhumanism

- https://sensetheatmosphere.wordpress.com/2013/10/25/why-does-macintyre-think-that-telling-stories-about-ourselves-is-important-to-constructing-who-we-are/

- https://www.wuw.pl/download-attachment.php?h=m7G5RMSUpaSXl2W3ksfK1dSVpXV1XIc%3D

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/the-narrative-self-philosophical-exploration

- https://www.sartreonline.com/Butler.pdf

Leave a comment