The Great Divide

The scientific community stands divided, locked in a battle over the most intimate aspect of human existence – consciousness[1]. This isn’t merely an academic squabble; it’s a fundamental disagreement about how we understand ourselves and our place in the universe[2] While neuroscientists map brain regions with increasing precision, the subjective experience of being conscious – the raw feeling of awareness – continues to elude our most sophisticated measuring tools[3].

Let’s be brutally honest: consciousness research is in crisis. Despite decades of intensive study and billions in research funding, we remain fundamentally unable to explain how neural activity translates into subjective experience[4]. The hard problem of consciousness, as David Chalmers famously termed it, stands as science’s most stubborn mystery[4].

The Measurement Problem

At the heart of this scientific impasse lies what we might call the measurement problem of consciousness[15]. How do we objectively measure something that is, by its very nature, subjective? The scientific method demands observable, repeatable measurements, yet consciousness exists primarily as private, first-person experience[15].

Current methods for measuring consciousness fall broadly into two categories: objective and subjective[16]. Objective measures examine observable characteristics like brain activity through fMRI or behavioural responses, while subjective measures rely on self-reports[16]. Both approaches face fundamental limitations when applied beyond human subjects[16].

The scientific establishment has largely embraced brain imaging technologies as the path forward. fMRI studies have identified specific brain regions and networks associated with consciousness, including the default mode network active during self-referential thinking and introspection[18]. Studies comparing brain activity during wakefulness, sleep, anaesthesia and disorders of consciousness reveal distinct patterns of activation related to different levels of awareness[18].

But let’s be clear – these correlations between brain activity and conscious states, while fascinating, don’t actually explain consciousness itself[3]. They merely describe what happens alongside it. This distinction is crucial and frequently overlooked by those eager to claim that science has “solved” consciousness[4].

The Reductionist Approach: Consciousness as Neural Activity

The dominant scientific paradigm approaches consciousness through a reductionist lens, attempting to explain subjective experience entirely through neural mechanisms[6]. This view holds that consciousness emerges from complex patterns of brain activity, with no need for anything beyond physical processes[6].

The neural correlates of consciousness are generated by synchronous activity across sensory and associative networks in the temporal, occipital and parietal regions[11]. According to this framework, conscious experience emerges through a hierarchical pathway beginning with brainstem and thalamocortical projections maintaining vigilance, followed by sensory processing in primary cortices, and finally distribution within associative networks[11].

Proponents of this view argue that recurrent processing – the continuous mutual exchange of information between specialised, associative and integrative areas – is essential for building conscious experience[11]. This recurrent processing enables widespread diffusion of information between brain regions processing different attributes of the conscious scene[11].

Yet this approach faces a fundamental challenge: explaining how objective neural processes generate subjective experience[6]. The explanatory gap between physical brain states and the qualitative nature of experience remains unbridged[4]. As Joseph Thompson pointedly observes, “Physicalism can explain only structure, function, and mechanism; but self-consciousness is always already embodied and embedded in multiple contexts beyond the structures and functions of brain activity”[6].

The Phenomenological Alternative: Experience First

Standing in opposition to reductionist approaches is phenomenology, which takes subjective experience as its starting point rather than attempting to reduce it to physical processes[5]. Phenomenology, developed by Edmund Husserl in the early 20th century, focuses on the detailed description of lived experience, seeking to understand how the world appears to us directly[12].

At its core, phenomenology examines how we experience things as they present themselves to our consciousness[12]. This is done by setting aside preconceived notions or theories (a process Husserl called “epoché” or “bracketing”) and focusing purely on the first-person perspective of experience[12].

Phenomenologists argue that consciousness is not just a passive reception of sensory data, but an active process of meaning-making and interpretation[5]. Consciousness is characterised by intentionality – it is always directed towards something, whether an object, another person, or an aspect of the environment[5]. This intentional structure highlights the fundamental relationship between consciousness and the world[5].

The concept of ‘being-in-the-world’, developed by Martin Heidegger, emphasises how human existence is fundamentally embedded in the world[5]. This challenges traditional notions of subject-object dualism and highlights the importance of context and embodiment in shaping conscious experience[5]. Consciousness needs to account for itself, to itself, on the terms in which it experiences itself[6].

The Radical Alternative: Panpsychism

Perhaps the most controversial approach to consciousness is panpsychism – the view that consciousness is not restricted to biological systems but is ubiquitous throughout the physical world[9]. According to this perspective, consciousness or mind-like aspects are fundamental features of reality[7].

Contemporary academic proponents of panpsychism hold that sentience or subjective experience is ubiquitous, while distinguishing these qualities from more complex human mental attributes[7]. They therefore ascribe a primitive form of mentality to entities at the fundamental level of physics but may not ascribe mentality to most aggregate things, such as rocks or buildings[7].

Panpsychism provides a way around the conundrum faced by both materialism and dualism[8]. Materialism can’t explain how matter produces consciousness; dualism can’t explain how immaterial consciousness interacts with matter[8]. Panpsychism suggests that consciousness did not evolve to meet some survival need, nor did it emerge when brains became sufficiently complex[8]. Instead, it is inherent in matter – all matter[8].

This view has gained traction among serious philosophers and scientists, including David Chalmers, who distinguishes between microphenomenal experiences (the experiences of microphysical entities) and macrophenomenal experiences (the experiences of larger entities, such as humans)[7]. Philip Goff draws a distinction between panexperientialism (conscious experience present everywhere at a fundamental level) and pancognitivism (thought present everywhere at a fundamental level)[7].

The Scientific Challenge: Measuring the Unmeasurable

The scientific study of consciousness faces a fundamental challenge: how to measure something that is inherently subjective[15]. Consciousness can only be measured through first-person reports, which raises problems about the accuracy of these reports, the possibility of non-reportable consciousness, and the causal closure of the physical world[15].

Scientists have developed various approaches to address this challenge. Integrated Information Theory (IIT), proposed by Giulio Tononi, claims that consciousness is identical to a certain kind of information, the realisation of which requires physical integration that can be measured mathematically[10]. This theory attempts to balance Cartesian intuitions that experience is immediate, direct and unified with neuroscientific descriptions of the brain[10].

Other researchers have focused on developing complexity measures to quantify states of consciousness[17]. These measures are important for assisting clinical diagnosis and therapy, particularly for patients with disorders of consciousness such as locked-in syndrome, coma or vegetative state[17].

Conclusion: The Way Forward

The debate over consciousness and subjective experience remains unresolved, with fundamental disagreements about how to study and explain this most intimate aspect of human existence[1]. The reductionist approach, seeking to explain consciousness entirely through neural mechanisms, faces the challenge of bridging the explanatory gap between physical brain states and subjective experience[6]. Phenomenology offers an alternative that takes subjective experience as its starting point, while panpsychism proposes a radical rethinking of consciousness as a fundamental feature of reality[5][7].

What’s clear is that no single approach has yet provided a complete explanation of consciousness[3]. The way forward likely involves integrating insights from multiple perspectives – neuroscience, phenomenology, philosophy of mind – while remaining open to radical new ideas[2]. As we continue to explore the nature of consciousness, we must remember that the most profound scientific advances often come from questioning our most basic assumptions about reality[4].

The consciousness conundrum reminds us that science, for all its power, still confronts mysteries at the very heart of human experience[3]. Perhaps that’s not a limitation, but an invitation to deeper understanding[2].

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

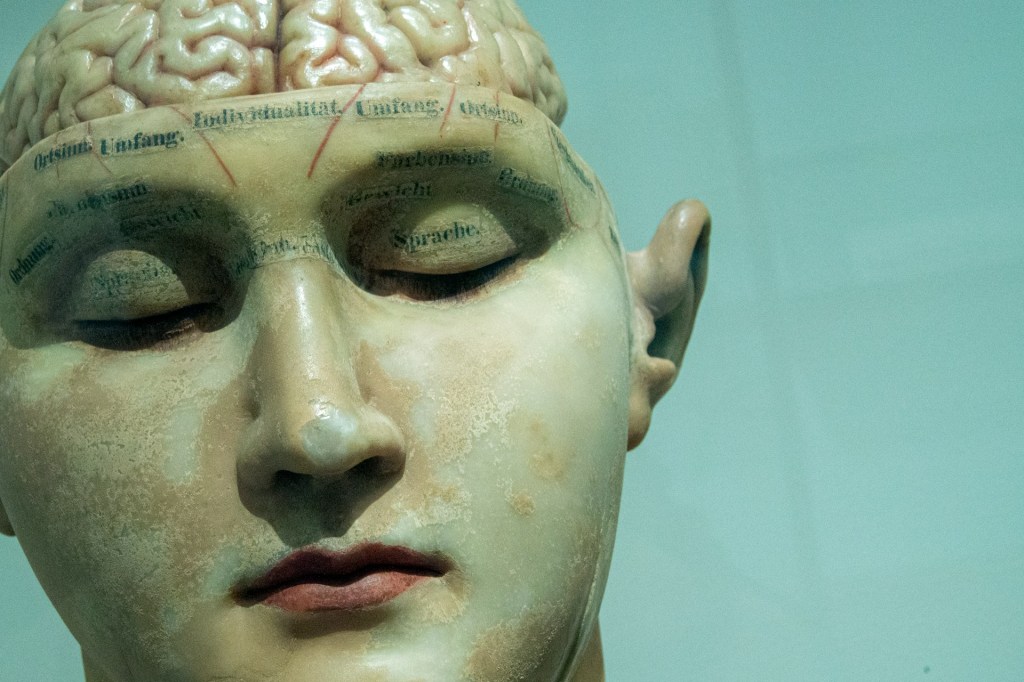

Photo by David Matos on Unsplash

References:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8888408/

- https://nerd.wwnorton.com/ebooks/epub/psychlife4/EPUB/content/3.1.1-chapter03.xhtml

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10267331/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_problem_of_consciousness

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/consciousness-in-phenomenology-guide

- https://www.atiner.gr/journals/humanities/2014-1-2-4-Thompson.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panpsychism

- https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/panpsychism-the-trippy-theory-that-everything-from-bananas-to-bicycles-are

- https://academic.oup.com/aristoteliansupp/article/95/1/51/6312909

- https://iep.utm.edu/integrated-information-theory-of-consciousness/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6842945/

- https://philosophy.institute/research-methodology/exploring-phenomenological-consciousness/

- https://news.wisc.edu/here-is-a-better-way-to-measure-consciousness/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/consciousness/comments/1c69ofn/panpsychism_the_radical_idea_that_everything_has/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4091309/

- http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/112783/1/The_Measurement_Problem_of_Consciousness_philtopics_preprint.pdf

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2018.00424/full

- https://brainlatam.com/blog/what-is-fmri-telling-us-about-consciousness-research-4919

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-41274-2

- https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=128000

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Embodied_cognition

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022519321003763

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subjective_character_of_experience

- https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcs.1697

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1697260024000401

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/panpsychism/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/is-consciousness-part-of-the-fabric-of-the-universe1/

- https://www.humanbrainproject.eu/en/follow-hbp/news/2023/08/30/measuring-consciousness-from-the-lab-to-the-clinic/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364661308001514

- https://life-longlearner.com/how-to-measure-consciousness-using-the-map-of-consciousness-3-of-7/

Leave a comment