The persistent tension between structural forces and individual agency represents more than an academic parlour game—it reflects a fundamental disagreement about how power operates in modern society and where responsibility lies for addressing persistent inequalities. This debate has intensified as neoliberal policies have reshaped social landscapes whilst digital technologies have created new forms of constraint, leaving scholars divided between those who emphasise systemic determinism and those who champion micro-level explanations. Yet this binary thinking often obscures the deeper truth: that structures and agency operate in tandem to reproduce existing hierarchies, and only by understanding their interaction can we develop effective interventions to promote genuine social justice.

The False Choice: Why the Debate Persists

The structure versus agency debate has plagued sociology since its inception, creating what appears to be an irreconcilable division between competing explanations of human behaviour[1]. On one side stand the structuralists, following Durkheim’s emphasis on social facts as external constraints that shape individual action[6]. These scholars argue that institutions, economic systems, and cultural norms determine outcomes far more than personal choice. On the other side, agency theorists trace their lineage to Weber’s focus on subjective meaning and individual action[7], insisting that people possess the capacity to resist, innovate, and transform their circumstances[16].

This apparent opposition has created a false choice that serves neither analytical rigour nor progressive politics. The persistence of this divide reflects deeper ideological commitments about responsibility and change. Structural determinists risk absolving individuals of moral agency whilst potentially discouraging activism. Agency advocates, meanwhile, can inadvertently blame victims for their circumstances whilst ignoring systemic barriers to advancement.

The debate’s intractability stems partly from its political implications. As one analysis notes, structuralism aligns with left-wing politics emphasising state intervention and rehabilitative justice, whilst agency-focused approaches support right-wing emphasis on individual responsibility and punitive measures[18]. This political dimension explains why the debate generates such heat—it’s ultimately about whether society should focus on changing systems or changing people.

Structural Forces in Contemporary Society

The evidence for structural determination remains overwhelming in contemporary Britain and beyond. Systemic racism exemplifies how deeply embedded institutional practices create differential outcomes regardless of individual merit or effort[10][15]. As research demonstrates, these systems operate through “complex arrays of practices, unjustly-gained political-economic power, continuing economic inequalities, and racist attitudes created to maintain and rationalise privilege”[10]. The structural nature of racism means it functions “increasingly covert, embedded in normal operations of institutions, avoiding direct racial terminology, and invisible to most Whites”[10].

Capitalism provides another clear example of structural constraint. Critics argue that the system creates “inherent biases favouring those who already possess greater resources”[11], leading to concentrations of wealth that undermine democratic governance. The profit motive encourages behaviour that prioritises capital accumulation over human wellbeing, creating what some scholars term “sociopathic reward structures” that systematically advantage the wealthy whilst marginalising working people[11].

Neoliberalism has intensified these structural constraints by reducing state capacity to counteract market failures[8]. The ideology’s emphasis on privatisation, deregulation, and tax cuts for the wealthy has systematically dismantled the public services that once provided genuine opportunities for social mobility. When Margaret Thatcher reduced top tax rates from 83% to 60%, she wasn’t just changing policy—she was restructuring incentives to favour capital over labour[8].

These structural forces operate through what Bourdieu termed “habitus”—the unconscious dispositions that guide behaviour and thinking[3][14][17]. Habitus represents “the way society becomes deposited in persons in the form of lasting dispositions or trained capacities”[3], creating seemingly natural patterns of thought and action that actually reproduce existing hierarchies. This concept reveals how structure operates not just externally through institutions, but internally through socialised expectations and self-limiting beliefs.

The Myth of Individual Agency Under Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism’s greatest ideological triumph has been convincing people that they are autonomous agents in a meritocratic system, even as it systematically constrains their choices. The rhetoric of individual responsibility masks the reality of diminished collective capacity to shape economic outcomes. When public services are privatised and social protections eroded, people face increased risks whilst possessing fewer resources to manage them.

The irony is stark. Neoliberalism promises greater freedom through market mechanisms, yet delivers what scholars term “systematic individual and interpersonal patterns” that perpetuate inequality[15]. The system creates artificial scarcity—in housing, healthcare, education, and employment—then blames individuals for failing to secure adequate access to these necessities.

Consider the contemporary housing crisis. Young people are told they cannot afford homes because they buy too many lattes or avocado toasts, whilst property speculation and restrictive planning laws create genuine shortages. This exemplifies how neoliberal discourse attributes structural problems to individual failings, deflecting attention from policy choices that favour property owners over renters.

The digital economy has intensified these dynamics. Platform capitalism creates the illusion of entrepreneurial freedom—anyone can drive for Uber or deliver for Deliveroo—whilst imposing algorithmic management that strips workers of traditional protections and collective bargaining power. The rhetoric of flexibility disguises new forms of exploitation that transfer risks from employers to workers whilst reducing wages and benefits.

Digital Constraints on Human Freedom

Digital environments have created unprecedented challenges to human agency that existing sociological frameworks struggle to address[9]. Modern technological features including “predictive algorithms and tracking tools pose four potential obstacles to the freedom of the self: lack of privacy and anonymity, embodiment and entrenchment of social hierarchy, changes to memory and cognition, and behavioural reinforcement coupled with reduced randomness”[9].

These constraints operate at both individual and collective levels. Algorithmic curation shapes what information people encounter, potentially reducing the diversity of perspectives that informed democratic deliberation requires. Filter bubbles and echo chambers don’t just reflect existing preferences—they actively reinforce them, creating feedback loops that polarise opinion and reduce common ground.

The surveillance apparatus of digital capitalism monitors and commodifies human behaviour in ways that fundamentally alter the relationship between self and society. When every click, search, and movement generates data that companies use to predict and influence future behaviour, the boundary between structure and agency becomes increasingly blurred. People make choices, but within parameters increasingly determined by algorithmic systems designed to maximise engagement and profit rather than human flourishing.

Yet these technological constraints aren’t inevitable. They reflect design choices made by corporations and policy decisions by governments. The European Union’s GDPR demonstrates that democratic societies can impose meaningful limits on surveillance capitalism. The question isn’t whether technology determines social outcomes, but whether democratic institutions have sufficient power to ensure technology serves human needs rather than corporate interests.

Beyond the Binary: Towards Synthesis

The most promising developments in contemporary sociology move beyond the structure-agency binary towards more nuanced understandings of their interaction. Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory proposes that “social structures are created and maintained through individuals’ actions, yet simultaneously constrain or guide those actions”[2]. This “duality of structure” recognises that structures both enable and constrain agency, whilst agency can reproduce or transform structures.

Margaret Archer’s morphogenetic approach provides another pathway beyond false binaries[4][5]. Her framework recognises that societies continuously balance between forces of stability and transformation through cycles involving structure, culture, and agency. Crucially, Archer emphasises that “change often emerges from a combination of slow, cumulative shifts in cultural values and sudden, disruptive events or crises”[4].

This synthetic approach has practical implications. Rather than choosing between structural reform and individual empowerment, progressive politics should pursue both simultaneously. Improving educational opportunities requires both better funding for schools (structural intervention) and programmes that help students develop aspirations and study skills (agency enhancement). Addressing racial inequality demands both anti-discrimination legislation and efforts to change attitudes and behaviours.

The key insight is that structure and agency operate through each other rather than against each other. Structural inequalities shape individual capacities and opportunities, whilst individual actions can cumulatively transform structural arrangements. Recognition of this interdependence points towards more effective strategies for social change.

Conclusion

The structure-agency debate will likely persist because it reflects genuine tensions in human experience between constraint and freedom, determination and choice. However, the debate’s political implications demand that we move beyond academic point-scoring towards frameworks that can guide effective action for social justice.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that structural forces—from systemic racism to digital surveillance—powerfully shape individual outcomes. Yet these structures are human creations that can be transformed through collective agency. The challenge is building institutions and movements capable of channelling individual energies towards structural transformation.

This requires honest acknowledgement of existing constraints alongside realistic assessment of possibilities for change. It means championing public services that provide genuine opportunities whilst criticising systems that perpetuate inequality. Most importantly, it demands recognition that the goal isn’t to resolve the structure-agency debate but to harness insights from both perspectives in service of human flourishing. Only by understanding how structures and agency interact can we build a society that expands genuine freedom for all rather than just the privileged few.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

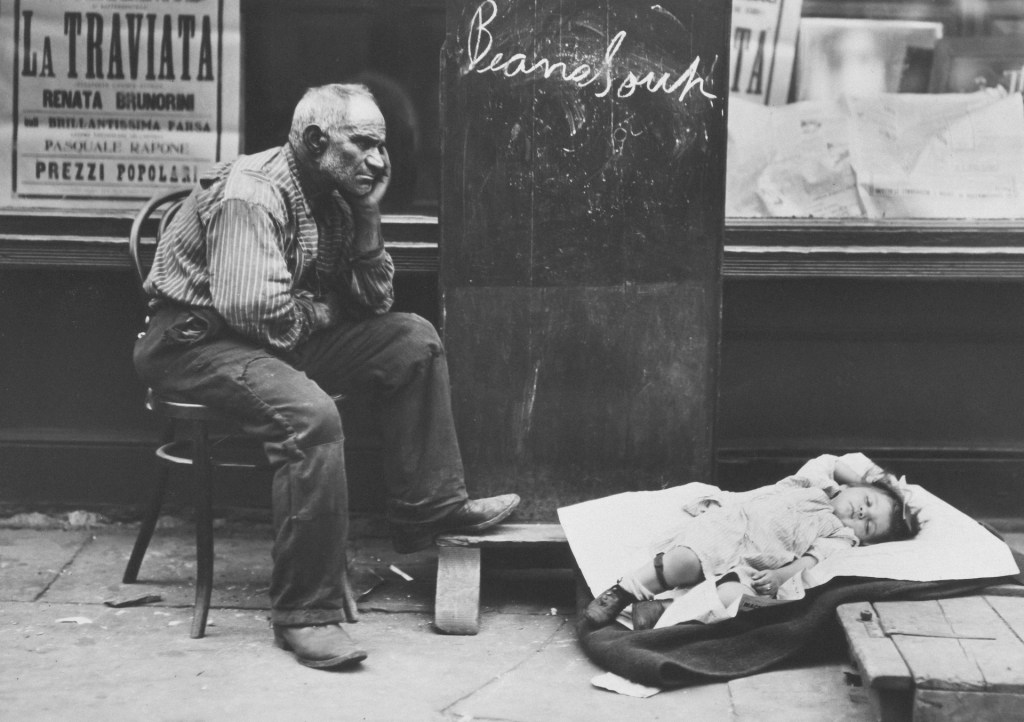

Photo by Art Institute of Chicago on Unsplash

References:

[1] Structure and agency – Wikipedia

[2] Structuration theory | EBSCO Research Starters

[3] Bourdieu and ‘Habitus’ | Understanding power for social change

[4] Understanding Social Change: Margaret Archer’s Morphogenetic …

[5] How to develop a realist programme theory using Margaret Archer’s …

[6] Durkheim and Social Facts | EBSCO Research Starters

[7] [PDF] sociology | semester-5 | cc-11 social action and ideal types

[8] What is Neoliberalism? – ReviseSociology

[9] Freedom and Constraint in Digital Environments: Implications for the …

[10] Systemic And Structural Racism: Definitions, Examples, Health …

[11] Criticism of capitalism – Wikipedia

[12] Structure and Agency Definition & Explanation | Sociology Plus

[13] [PDF] A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation

[14] Habitus (sociology) – Wikipedia

[15] Systemic racism: individuals and interactions, institutions and society

[16] The Agency vs Structure Debate – Easy Sociology

[17] Pierre Bourdieu & Habitus (Sociology): Definition & Examples

[18] Can you explain the difference between structure and agency?

[19] Habitus (Chapter 3) – Pierre Bourdieu – Cambridge University Press

[20] Structure and Agency – Stones – Major Reference Works

[21] [PDF] Structure and Agency – STUART MCANULLA

[22] Sage Reference – Agency-Structure Debate

[23] Structure and Agency and the Sticky Problem of Culture – jstor

[24] Pierre Bourdieu: Habitus – Critical Legal Thinking

[25] Structure, Culture and Agency: Selected Papers of Margaret Archer

[26] TM5a – Social Action Theory / TM5 – Hectic Teacher Resources

[27] “Neoliberal Agency” – jstor

[28] Neoliberalism (Education) | Topics | Sociology – Tutor2u

[29] Agency and neoliberalism – jstor

[30] A Definition and Overview of Systemic Racism – ThoughtCo

[31] Institutional racism – Wikipedia

[32] Levels of Racism: Systemic vs Individual – Anti-racism Resources

[33] How systemic racism affects young people in the UK – Barnardo’s

[34] Habitus: Definition & Examples (Easy Explanation) – YouTube

[35] Margaret Archer’s Final Book: Morphogenesis Answers Its Critics …

[36] What are ‘Social Facts’ ? – ReviseSociology

[37] Social fact – Wikipedia

[38] Social Facts (Explained in 3 Minutes) – YouTube

[39] Sociology 250 October 26, 1999 Social Facts and Suicide

[40] Agency | Reference Library | Politics – Tutor2u

[41] Durkheim, Emile | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

[42] Agency and neoliberalism | Cambridge Journal of Economics

[43] Embracing Digital Sociology To Unlock The Next Marketing Frontier

[44] Platform capitalism – Wikipedia

[45] Neoliberalism: A Concept Every Sociologist Should Understand

[46] SOCIOLOGICAL IMAGINATION AND SOCIAL AGENCY IN THE …

[47] Agency Capitalism in Private Markets: Who Watches the Agents?

[48] Karl Marx critique of capitalism | Marxist theory explained – YouTube

[49] Agency Capitalism: Further Implications of Equity Intermediation

Leave a comment