The library smelled of damp paper and forgotten summers. I pressed my palm against the oak card catalogue, its brass knobs dulled by decades of fingertips. Tomorrow, they’d haul it to the tip. Today, it still held ghosts.

“Miss Hargreaves?” The councilman’s polished shoes clicked across the parquet. “We’ve brought the boxes.”

I didn’t turn. Let him hover. Let him jangle his keys like a jailer. Outside, rain smudged the Yorkshire moors into a watercolour wash, the same grey-green as my father’s eyes. Before the internet, I wanted to tell this smooth-faced man, we learned the weather from bones. From the ache in Gran’s knuckles, the way crows gathered on the church spire. Now they check apps, these children. They’ve never tasted a storm coming.

“The boxes,” he repeated.

“Start with periodicals.” My voice surprised me—still crisp, still the head librarian’s bark. “1923 to 1997. Alphabetised.”

As his lackeys shuffled off, I slipped a yellowed index card into my pocket. Woolf, V. – To the Lighthouse. Last borrowed: 14/03/1989. Margaret Towne’s spidery signature blurred under my thumb. Margaret, who’d died thinking email was something you posted through a slot.

The computer terminals sat shrouded in dustsheets. We’d got them in ’98, when the council said digital or die. I’d watched teenagers poke at keyboards like anthropologists baffled by artefacts. Now they’re buried in phones, drowning in light.

I moved past Philosophy (unloved since Nietzsche went out of fashion) to the back room. My fingers found the loose floorboard without looking. The tin box emerged, rust singing against nailheads.

Inside: a ticket stub from The Phantom of the Opera, London, 1987. A lock of hair—auburn, shot with silver. And the photograph.

Do you remember life before the internet, Evie?

His voice, always half a laugh. Thomas Merriweather, who’d kissed me in the stacks between Religion and Ancient History. Who disappeared two weeks before broadband came to Crowsbeck.

June 1989

The bell jangled as Thomas burst in, trailing peat smoke and mischief. “Evie! You’ll never guess.”

I glared over my glasses. “It’s 8:03.”

“Precisely.” He slapped a flyer on the counter—INTERNET: Gateway to the Future! Public Demonstration, Town Hall, 14th June. “They’re calling it the information superhighway. Sounds like a motorway for nerds.”

I inked the date stamp harder than necessary. Mrs. Pettigrew’s romance novel thumped closed. “We have encyclopaedias.”

“But imagine! Talking to New York in real time. Reading Australian newspapers.” He leaned close, smelling of roll-ups and the cinnamon gum he chewed to hide them. “We could look up… oh, anything. Who really killed Kennedy.”

“The CIA,” muttered old Mr. Briggs from Travel Guides.

Thomas’s grin faltered as I reshelved Dostoevsky. He knew my rules: no politics, no conspiracy theories, no modern nonsense. The library was a sanctuary. A temple of physical truth.

That night, he found me cataloguing donations. His hands were shaking.

“They’ve arrested Danny Cole.”

The name hung between us. Danny—Thomas’s cousin, the boy who’d painted Trotsky Lives! on the war memorial last May.

“For what?”

“They’re saying he burned down the telecoms hut.” His laugh cracked like ice. “The one that was supposed to bring us this bloody internet. He’s been in Whitby visiting his gran!”

I touched his wrist. Calluses from hauling fishing nets. “We’ll prove it.”

“How? The police have ‘computer evidence’.” He spat the words. “Some… algorithm says he did it.”

The overhead lights buzzed. Somewhere, a pipe dripped.

“Then we’ll find real evidence,” I said.

We became detectives

Thomas charmed the postmistress into lending her bicycle. I dug out maps from 1946—the last time Crowsbeck had arsonists. Each morning, we’d meet by the Bronze Age burial mound (our “office”, Thomas called it) and compare notes.

“The telecoms hut had security cameras,” I reported, flipping open my notebook. “But the system was analogue. Footage stored on VHS tapes.”

Thomas whistled. “Which the coppers conveniently lost?”

“Or someone took.” I hesitated. “The fire chief’s nephew works at the video rental shop.”

His eyes lit. That dangerous, beautiful light.

We broke into the rental shop at midnight. The moon painted the horror section in silver—Friday the 13th leering from covers. Thomas picked the back door lock with a hairpin.

“Where’d you learn that?” I hissed.

“From the internet.” His smirk faded. “Well, a magazine about hackers.”

The security tapes were labelled in green Sharpie: Telecoms Hut – June 8. My hands shook as we slotted it into the VCR.

Grainy footage showed figures in balaclavas. Not Danny’s lanky frame. One arsonist limped—left leg dragging.

“Like Billy Shanks,” Thomas breathed. The butcher’s son, who’d smashed his hip falling drunk into a ravine. Whose father played poker with the police chief.

We copied the tape. Mailed it to the Whitby Gazette.

Danny walked free. The real arsonists got six months.

Thomas kissed me that night, his mouth bitter with adrenaline. “You’re brilliant, Evie Hargreaves.”

I should’ve known it wouldn’t last.

Present Day

The councilman clears his throat. “We’re done with periodicals.”

I snap the tin box shut. Outside, diggers growl. They’ll build a “community hub” here—touchscreens, VR headsets, a Costa Coffee. Progress.

“Miss Hargreaves? Your taxi’s here.”

The photograph burns in my pocket. Thomas, grinning by the stone circle, hair whipped by wind. Two weeks after Danny’s release, he’d left a note: Gone to find the truth. Don’t wait.

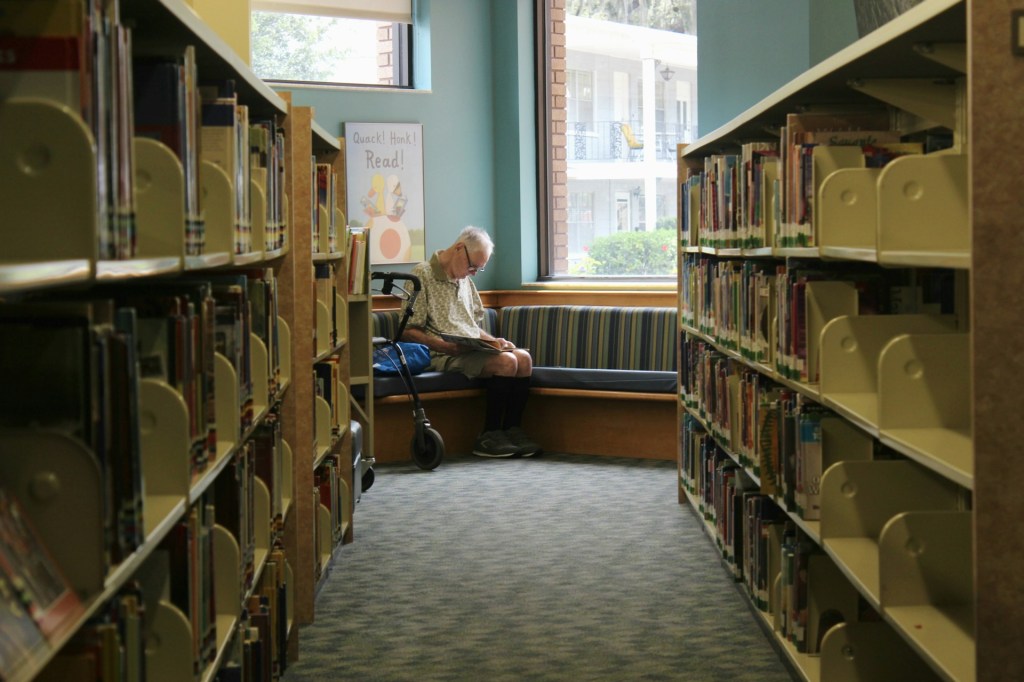

I know what happened. The same thing that happens to all of us who remember card catalogues and the weight of a book in your lap. We become ghosts.

At the door, I press my forehead to the stained glass. Violet and gold light paints my wrinkles.

“Goodbye,” I tell the shadows.

The taxi driver stares at his phone. I roll down the window.

Rain. Earth. The sharp green scent of hawthorn.

Somewhere, a crow laughs.

THE END

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Photo by Lindy Maio on Unsplash

Leave a comment