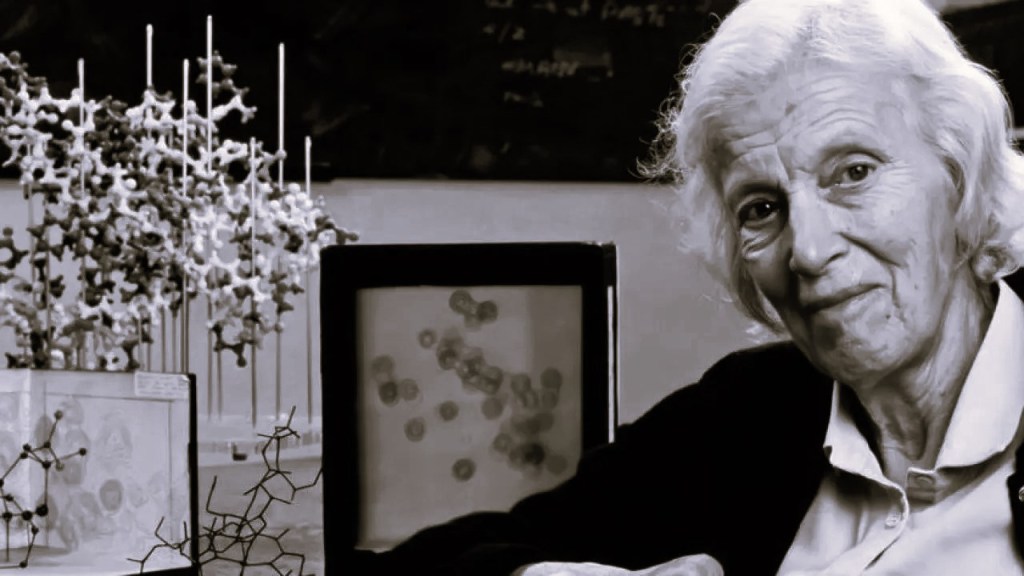

Here is a stark fact that should shame our collective memory: Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin remains the only British woman ever to win a Nobel Prize in the sciences, yet her name draws blank stares whilst her male contemporaries enjoy household recognition. This is not merely an oversight—it is a damning indictment of how systematically we erase women’s contributions to human knowledge. Hodgkin’s revolutionary work with X-ray crystallography unlocked the structures of penicillin, vitamin B12, and insulin, discoveries that have saved countless millions of lives. Yet when she won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964, the Daily Mail’s headline read “Oxford housewife wins Nobel”. The deliberate diminishment of her achievements tells us everything about the forces that conspire to keep brilliant women in the shadows.

A Revolutionary Scientific Pioneer

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin didn’t just advance science—she transformed it. Born in Cairo in 1910 to parents working in Britain’s colonial administration, she was “captured for life by chemistry and by crystals” at the tender age of ten. This early fascination would blossom into a career that fundamentally changed how we understand the molecular world.

At Oxford University, where she studied from 1928 to 1932, Hodgkin pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of complex biological molecules. This technique, which involves passing X-rays through crystallised substances to capture diffraction patterns, was considered avant-garde and unreliable by traditional chemists. Yet Hodgkin possessed the mathematical brilliance, manual dexterity, and sheer determination to push this method far beyond what anyone thought possible.

Her first triumph came during the Second World War when she tackled penicillin’s structure. Ernst Chain, part of the team developing this life-saving antibiotic, issued her a direct challenge: solve penicillin’s molecular structure to aid mass production. Working in secrecy as part of the war effort, Hodgkin and her team cracked the puzzle by 1945—Victory in Europe Day, no less. When she insisted the molecule contained a beta-lactam ring (a structure thought too unstable to exist), established chemists scoffed. John Cornforth famously declared: “If that’s the formula of penicillin, I’ll give up chemistry and grow mushrooms”. He was wrong. Hodgkin was right. Her discovery became the foundation for developing modified penicillins that continue saving lives today.

But penicillin was merely the beginning. In 1956, she solved the structure of vitamin B12, a molecule so complex it has the most intricate structure of any known vitamin. This achievement required using Alan Turing’s Pilot ACE computer—early recognition that the future of structural biology lay in computational power combined with experimental ingenuity. The vitamin B12 work directly contributed to her Nobel Prize in 1964, making her only the third woman in history to win the Chemistry prize.

Battling Prejudice and Physical Pain

What makes Hodgkin’s achievements even more remarkable is that she accomplished them whilst facing systematic discrimination and debilitating illness. As a woman in 1930s academia, she encountered barriers at every turn. When she graduated from Oxford with excellent marks, she struggled to find work simply because of her gender. It was only through the intervention of J.D. Bernal at Cambridge that she found her first real opportunity.

Even after establishing herself as a leading scientist, the prejudice continued. At Oxford, she became the first woman to receive paid maternity leave—a groundbreaking achievement that she had to fight for. She delivered presentations to the Royal Society whilst visibly pregnant, challenging conventions about women’s roles in academic life. Yet despite her obvious brilliance, Oxford was slow to promote her, only making her a Reader in X-ray Crystallography in 1955—years after her international reputation was established.

Perhaps most cruelly, Hodgkin developed chronic rheumatoid arthritis in her late twenties, following an infection after her first child’s birth. This condition left her hands swollen and distorted throughout her career—a devastating affliction for someone whose work required the most delicate manual manipulation of crystals and equipment. Yet she refused to be deterred. Colleagues marvelled at her ability to continue the intricate work of crystallography despite hands that were increasingly gnarled and painful.

Her left-wing political views also created obstacles. The McCarthyist paranoia of the 1950s saw her denied a US visa from 1953 to 1990 because of her association with Communist Party members, including her husband Thomas and mentor Bernal. This denied her access to crucial American collaborations during the height of the Cold War.

The Insulin Triumph and Lasting Impact

Hodgkin’s greatest scientific obsession was insulin—the hormone that regulates blood sugar and whose discovery had already revolutionised diabetes treatment. She first photographed insulin crystals in 1934 and called it “probably the most exciting moment in my life”. For 35 years, she pursued insulin’s complete structure, finally achieving success in 1969.

This wasn’t merely academic curiosity. Insulin research was driving multiple Nobel Prizes, with Frederick Sanger winning for determining its amino acid sequence in 1958, and Rosalyn Yalow later winning for developing radioimmunoassays to measure insulin. Hodgkin’s structural work completed the picture, providing the three-dimensional architecture that explained how this crucial molecule functions.

Her influence extended far beyond her own discoveries. Students from around the world flocked to her Oxford laboratory, which colleagues described as “truly multi-national” and “very ahead of its time”. She mentored generations of crystallographers, including future Nobel laureates. Even Margaret Thatcher, despite their vastly different politics, maintained contact with her former chemistry tutor throughout her political career.

The Scandal of Selective Memory

Why has Dorothy Hodgkin been forgotten whilst her male contemporaries achieved lasting fame? The answer reveals uncomfortable truths about how we construct scientific narratives. James Watson and Francis Crick became household names for their DNA structure work, yet Hodgkin’s contributions to understanding equally fundamental molecules remain obscure. Max Perutz and John Kendrew won Nobel Prizes for protein structures that built directly on techniques Hodgkin pioneered, yet they receive greater recognition.

The pattern is clear and damning. When women make scientific breakthroughs, their achievements are minimised, their methods questioned, their personal lives scrutinised instead of their professional accomplishments. The Daily Mail’s “housewife” headline wasn’t an aberration—it was emblematic of systematic efforts to diminish women’s intellectual achievements by reducing them to domestic roles.

This erasure has consequences. Young women entering STEM fields need role models who look like them, who faced similar obstacles and overcame them through brilliance and determination. By forgetting Dorothy Hodgkin, we rob future generations of inspiration and perpetuate the myth that scientific genius is a masculine trait.

A Legacy Demanding Recognition

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin died in 1994, having received the Order of Merit, the Copley Medal, and numerous other honours. She was Chancellor of Bristol University for 18 years and devoted her later years to peace activism and nuclear disarmament. Yet outside specialist circles, her name remains unknown.

This must change. In an age when we finally recognise that diversity drives innovation, Hodgkin’s story offers a blueprint for excellence achieved against overwhelming odds. Her techniques continue underpinning modern drug discovery. Her approach to international scientific collaboration presaged today’s global research networks. Her combination of rigorous methodology with humanitarian values shows science at its finest.

Dorothy Hodgkin proved that brilliance transcends gender, that determination conquers prejudice, and that one person’s discoveries can benefit all humanity. The scandal is not that she was forgotten—it’s that we allowed her to be forgotten. Rectifying this oversight isn’t just about historical justice. It’s about ensuring that future Dorothy Hodgkins receive the recognition they deserve whilst they’re still alive to see it.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment