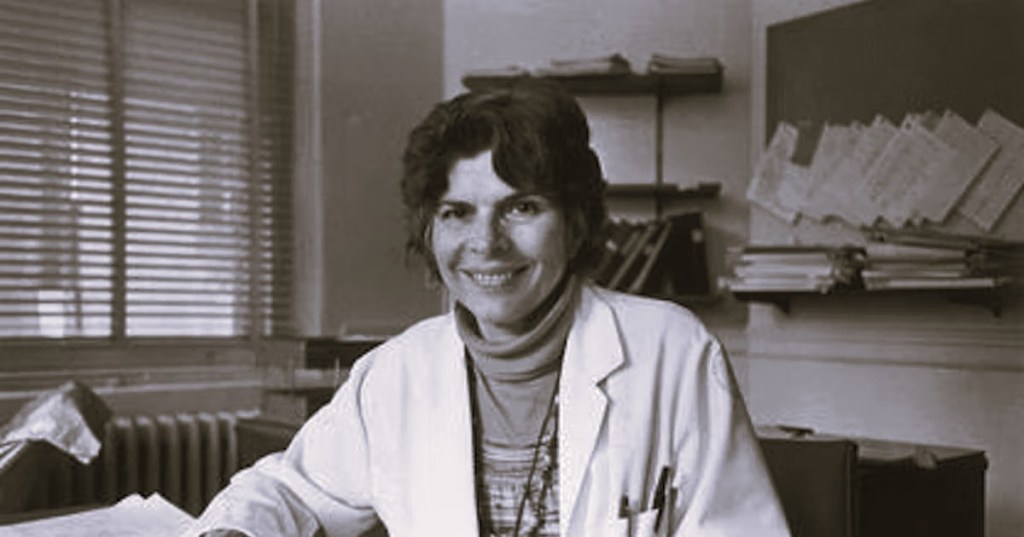

Here stands a woman whose name should echo through every hospital corridor and public health office, yet remains shamefully absent from most medical textbooks. Dr Helen Rodríguez-Trías didn’t just practice medicine—she wielded it as a weapon against injustice, slashing infant mortality rates by half and dismantling systems designed to rob women of their reproductive autonomy. Born in 1929 to Puerto Rican parents in New York City, she became the first Latina president of the American Public Health Association whilst simultaneously exposing the grotesque sterilisation abuses targeting women of colour. Her legacy is not merely one of medical excellence, but of moral courage that challenged an entire establishment and won.

From Discrimination to Determination

The roots of Rodríguez-Trías’s fierce advocacy were planted early in the toxic soil of American racism. When her family returned to New York from Puerto Rico when she was ten, she encountered the full force of institutional prejudice. Despite excellent grades and fluency in English, school administrators dumped her into classes for students with learning disabilities—a casual cruelty that would have broken lesser spirits. Only when a teacher witnessed her reciting poetry did anyone recognise her exceptional abilities and move her to appropriate classes.

This wasn’t mere bureaucratic incompetence. It was systematic racism, designed to crush the potential of Puerto Rican children. Yet rather than retreating, Rodríguez-Trías absorbed these lessons about power, privilege, and the machinery of oppression that would fuel her lifelong mission. She chose medicine precisely because it “combined the things I loved the most, science and people”, understanding instinctively that healing bodies meant fighting the systems that made them sick.

Her educational journey took her back to Puerto Rico, where she earned her medical degree with highest honours from the University of Puerto Rico in 1960. By then, she was already a formidable activist, deeply involved in the Puerto Rican independence movement. At thirty-one, divorced twice with four children, she faced obstacles that would have deterred most. Instead, she graduated at the top of her class whilst giving birth to her fourth child—a feat that speaks to extraordinary determination.

Revolutionary Healthcare in Puerto Rico

Rodríguez-Trías’s first major victory came during her residency in Puerto Rico, where she established the island’s first centre for newborn care. The results were nothing short of revolutionary: within three years, infant mortality at University Hospital in San Juan plummeted by fifty percent. This wasn’t just good medicine—it was proof that proper healthcare could transform entire communities when delivered with competence and compassion.

Her approach was radically different from the paternalistic medicine of the era. She understood that effective healthcare required addressing social and economic inequalities, not merely treating symptoms. This insight would prove prophetic, anticipating modern public health approaches by decades. Yet even as she saved countless lives, Rodríguez-Trías was quietly documenting a more sinister reality that would soon dominate her career.

The Battle for Lincoln Hospital

In 1970, Rodríguez-Trías returned to New York to head the paediatrics department at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx. The timing was explosive. Lincoln Hospital, known locally as the “Butcher Shop,” served predominantly Black and Latino patients whilst maintaining appalling standards of care. That same year, the Young Lords—a Puerto Rican civil rights organisation—occupied the hospital, demanding basic dignity for their community.

Rather than dismissing these activists as troublemakers, Rodríguez-Trías recognised their legitimacy. She worked to train her staff on the needs of Puerto Rican patients and sought common ground with community organisers. This wasn’t mere politics—it was revolutionary medicine that recognised patients as people with agency and rights. Her approach helped produce one of the first Patient’s Bills of Rights, fundamentally changing relationships between hospitals and patients nationwide.

Exposing the Sterilisation Scandal

Whilst building bridges at Lincoln Hospital, Rodríguez-Trías uncovered evidence of systematic sterilisation abuse that would define her most important battle. In Puerto Rico, approximately thirty percent of women of reproductive age had been sterilised, often without proper consent. Women were pressured to sign forms immediately after delivery, whilst weak and vulnerable, without understanding that “La Operación” was irreversible.

This wasn’t healthcare—it was eugenics, dressed in medical language but rooted in colonial contempt for Puerto Rican women. Rodríguez-Trías understood that these abuses reflected “race and class differences” in how reproductive rights were applied. Wealthy white women fought for access to legal abortion whilst poor women of colour were sterilised against their will—two sides of the same coin of reproductive oppression.

Her response was characteristically direct. In 1974, she founded the Committee to End Sterilisation Abuse and later the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilisation Abuse. These weren’t merely advocacy groups—they were legal and political machines that exposed abuses across inner-city hospitals throughout the United States. Her work was instrumental in establishing the 1978 Federal Sterilisation Regulations, which mandated informed consent, waiting periods, and protections against coercion.

Transforming AIDS Care

The 1980s brought a new challenge that would cement Rodríguez-Trías’s reputation as a public health visionary. As medical director of the New York State AIDS Institute from 1987 to 1989, she confronted a disease that was devastating marginalised communities whilst being ignored by much of the medical establishment. Her work establishing HIV standards of care, particularly for women and the poor, created a model that spread nationwide.

This wasn’t accidental excellence—it was the logical extension of her career-long focus on health equity. Whilst others saw AIDS as a moral failing, Rodríguez-Trías saw a public health crisis requiring compassionate, evidence-based intervention. Her approach saved thousands of lives and established principles of care that remain relevant today.

Leadership and Recognition

Throughout her career, Rodríguez-Trías shattered barriers with systematic precision. She co-founded both the Women’s Caucus and the Hispanic Caucus of the American Public Health Association in the 1970s. In 1993, she became the first Latina president of the APHA, using the platform to champion health equity and reproductive freedom.

Her influence extended far beyond the United States. She worked to expand public health services for women and children across Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. This global perspective reflected her understanding that health inequities were universal problems requiring coordinated solutions.

In 2001, President Bill Clinton awarded her the Presidential Citizens Medal, the second-highest civilian honour in the United States. The recognition came barely a year before her death from lung cancer, a cruel irony for someone who spent her life fighting preventable diseases.

The Continuing Struggle

Today, many of the battles Rodríguez-Trías fought remain unfinished. Sterilisation abuse continues in American prisons, with 148 female prisoners sterilised in California facilities between 2006 and 2010 without proper consent. Reproductive rights face renewed assault, whilst health inequities persist across racial and economic lines.

Her example remains urgently relevant. Rodríguez-Trías proved that medical expertise combined with moral courage could dismantle systems of oppression and save lives. She understood that true healthcare required fighting not just disease, but the social conditions that create illness. Her work demonstrates that the most effective medicine often happens outside hospital walls, in courtrooms, legislatures, and community meetings where power is contested and justice won.

Dr Helen Rodríguez-Trías deserves recognition not merely as a pioneering physician, but as a model for what medicine can accomplish when practitioners remember that healing requires justice. Her legacy challenges every healthcare professional to ask not just how to treat disease, but how to transform the systems that create it. In forgetting her, we risk losing sight of medicine’s highest calling: the radical notion that everyone deserves dignity, agency, and care.

Bob Lynn | © 2025 Vox Meditantis. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment